Psychosis and Ethnicity: Understanding Barriers in Pathways to Care

Rebekah FA Gee, Santanu Chakrabarti, Hari Subramaniam, Elizabeta B Mukaetova-Ladinska*

West Park Hospital, Edward Pease Way, Darlington, DL2 2TS

The Evington Centre, Gwendolen Road, Leicester, Leicestershire, LE5 4 QG, UK

Department of Neuroscience, Psychology and Behaviour, University of Leicester, Leicester LE1 7RH

Received Date: 16/06/2021; Published Date: 01/07/2021

*Corresponding author: Elizabeta B Mukaetova-Ladinska, MD, PhD, MRCPsych, Department of Neuroscience, Psychology and Behaviour, The Maurice Shock Building Room 332, University of Leicester LE1 7RH, Leicester, UK. Email: eml12@le.ac.uk

Abstract

Across the UK, different ethnic groups present with differing rates and experiences of mental health problems, particularly psychosis, which is reflection on their diverse cultural and socioeconomic background. It is essential that all ethnic groups have access to appropriate treatments. In general, people from ethnic minority groups are more likely to be diagnosed and admitted to hospitals due to their underlying mental health problems. Their prognosis and engagement with mental health services appears to be poorer in comparison to the white indigenous population. These differences are reported across adult ethnic minority population; however very little is known about the prevalence, clinical phenotype, access to mental health services and the prognosis for their older counterparts.

In the current study we provide an overview of the clinical presentation, management, and impact on the life of people from ethnic minority background affected with psychosis. The evidence comes predominantly from younger people, while very little work has been conducted on late-onset psychosis. Given the rapidly growing ethnic minority population living in the UK and the rest of the developing countries, similar work needs to be extended to the older people. For many it will be the first time they be in touch with mental health services, and they may well require different service provision to meet their needs.

Introduction

Psychosis and ethnicity

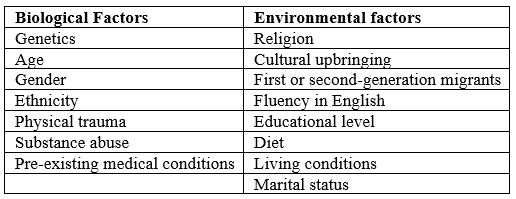

Multicultural societies present a challenge for mental health services. People from ethnic minority background may present with psychosis differently compared to white indigenous populations. These differences include the excess prevalence rates of diagnoses of psychosis, presentation of symptoms and the effectiveness of the antipsychotic treatment [1] pathways to care [2]. Patients from ethnic minority background are more likely to receive a diagnosis of psychosis, in particular schizophrenia, be admitted to mental health hospitals more readily and for extended periods than the white indigenous people [3]. They also appear to be treated with higher doses of conventional antipsychotic medication (including depot medication) and not the second-generation antipsychotics [1]. Furthermore, their outcome is generally poorer, and this has been attributed to biological and environmental factors (Table 1). The majority of the discrepancies found between the ethnic minority and white indigenous populations are reported across all age groups.

People from ethnic minority background with psychosis tend to use emergency over planned mental health services [1]. This ad hoc utilisation of psychiatric services is, not surprisingly, reflected in the mental health problems associated with deliberate self-harm. Thus, 74% of black Caribbeans that committed suicide had a schizophrenia diagnosis, which was the highest in comparison to other ethnic groups [4].

McGovern et al [5] highlighted four factors that had a significant negative impact upon patients’ clinical outcomes - living alone, unemployment, conviction rates and imprisonment. Moreover, research led by Hunt et al [4] into suicides among ethnic minority groups analysed a four-year sample and found that patients that committed suicide within 12 months of contact with mental health services had a specific social profile, in terms of being unemployed, living alone and being unmarried, with these being more characteristic for the Black Caribbean. Interestingly, black patients with psychosis appear to be more likely treated in forensic settings, such as prisons and secure units, when readmitted [5]. A recent meta-analysis similarly confirmed that many people from ethnic minorities (i.e, black Caribbean or African origins and those from Asian background) with psychosis arrive at mental health services via the criminal justice system [6].

Table 1: Biological and Environmental factors that affect presentation and prognosis in psychotic illnesses (modified after [1]). (Maura & Weisman de Mamani, 2017)

Factors Influencing Help-Seeking Behaviour in serious mental illness

Early access to appropriate medical care can minimise the sequelae of mental illnesses. In the white indigenous population with mental health illness, help-seeking attempts start as early as prodromal phase of the illness and continue well into the psychotic phase, with higher number of contacts with both primary care physicians and mental health professionals [7], with the emergency services being often the contact that helped individuals obtain appropriate treatment for their psychosis [8]. This contrasts with people from ethnic minorities, who appear to be in contact with the mental health services as a result of compulsory admission, police or criminal justice system contact, but low probability of GP involvement [6].

There appears to be a barrier between ethnic minority populations and mental health services, and it has been queried whether this is due to racism within the services themselves. In addition, a serious mistrust between mental health staff and patients with ethnic minority background, in particular black young men, has also been described [9]. There are major discrepancies between the attitudes of ethnic minority and white patients towards mental health and treatments. This seems to originate from a variety of factors, including, but not limited to, religion, cultural upbringing, educational level as well as alcohol and drug consumption.

Keating and Robertson’s study [9] investigated the role of fear within black patient’s willingness to seek and accept help for a mental illness and the role of fear within the treatment teams. The study found that clinicians appear to be fearful of openly and honestly discussing race and possible racism or prejudice and stated there was little difference in the treatment of black versus white people. However, this opinion was not shared by black patients: black patients who participated within this study spoke of unfair and unjustified treatment when compared to white patients [9]. Interestingly, a recent study found similar results when investigating disproportionate detention of patients with ethnic minority background, under the Mental Health Act: 63.58% of these patients who were assessed under the Mental Health Act, were detained [10].

In addition, the Government figures released in 2019 showed 288.7 out of 100,000 Black, 91.9 out of 100,000 Asian and 158.4 out of 100,000 mixed race people were detained under the Mental Health Act in the 2017/18 period. In comparison 71.8 out of 100,000 white people were detained under the Mental Health Act in the same period (2017/18 period) [11]. However, Gajwani et al [10] noted this was not due to racism or discriminatory actions, but a higher rate and severity of mental illnesses within the ethnic minority population, alongside with reduced social support and cultural differences.

Comparatively, Adams et al [12] conducted an investigation into the influence of race on primary care doctors’ decision making in regard to depression. Surprisingly, the authors found less attention being paid to the potential outcomes associated with differing treatment options for people from ethnic background compared to white patients. The study also found there was a greater level of clinical uncertainty in diagnosing depression amongst black compared to white patients and a tendency for clinicians to attribute the depression to a physical cause rather than psychological symptoms [12]. These findings call for a greater understanding the differences in symptomology, treatments and social factors in mental health disorders, including psychosis, that differ in ethnic minority when compared to the white population.

Mantovania et al [13] suggested, in order to tackle the ethnically based disparities, clinicians need to take other factors, such as race/ethnicity, religion and culture into account when diagnosing and treating patients from ethnic background. This is incredibly important as an earlier study found most black patients and relatives thought all black day centres would be beneficial, in spite of concerns that this would lead to more segregation and taking steps backwards into forced segregation [14]. These findings, nevertheless, indicate that black patients feel they are not receiving adequate or equal care by white clinicians or staff members. However, it is still not clear whether the difference in treatment is down to racism or the severity of illness in black patients, when compared to white patients. Whether this is the case for other ethnic minorities, i.e., Chinese. Pakistani, Indian, non-indigenous white people, remains unknown.

The Impact of Stigma on Help-Seeking Behaviour

Black patients also noted a particular perceived stigma among family and friends surrounding mental illness. An earlier study addressed attitudes towards mental illness and psychiatric services of second-generation Afro-Caribbean’s and white British people who were inpatients in mental health wards and highlighted differences in attitudes [14]. Thus, black relatives of patients admitted with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, were significantly more likely to attribute the illness to substance use and supernatural causes and view the services and clinicians as racist [14, 15]. Stigma can occur not only on a social level, but on personal level (self-stigma) and a structural level; these different types of stigma do; however, all interlink and perpetuate each other [13].

Although psychosis and mental illness in general are not without stigma or taboo in the white indigenous population, there are much greater levels of social stigma within the ethnic minority populations, who are less knowledgeable about such illnesses. Within these communities, culturally there are many factors that lead to people not seeking help when dealing with a mental illness. An investigation into the understanding of mental health in the ethnic community found their attitudes towards mental health differ to those of the white community [16]. The study highlighted there is a large prominence in ethnic communities of ‘keeping problems within the family’ and not exposing oneself to be mentally ill. Participants within the study spoke of their parents worries of the family name being tarnished if it were associated with mental illness and this could lead to disownment in some cases. This isolates the person suffering with psychosis and often can make them feel like there is no way out, lead to suicide and may be a contributing factor to the disproportional amount of suicide among people with ethnic background within the UK [4, 16].

Another contributing factor that adds to the societal stigma of mental illness, including psychosis, is the yearning to appear strong, proud and resilient constantly within ethnic communities [16]. Furthermore, serious mental illness is often seen as a sign of cognitive and/or psychological weakness, bad parenting, or bad morals. The concept of appearing weak, especially in front of white people, is very frowned upon within some of these communities [16, 17]. This may stem from the fact many ethnic communities have had to fight for their existence for many years, throughout wars and slavery, and there is still the worry that people from ethnic minority background should never show signs of weakness [18]. It could be argued this is exacerbated because of problems with perception of mental illness within their communities. A report exploring perceptions of mental illness within India, highlighted a real lack of understanding of what mental health is [19]. Although this report was conducted within India the findings arguable should be applicable wider. The report found 62% of participants used derogatory terms to describe people with mental illness, such as ‘retard’ and ‘crazy/mad/stupid’, with 40% of the participants disclosing it was frightening and dangerous to have mentally ill people living within their neighbourhood. Additionally, a shocking 68% of participants felt that if a person is mentally ill, they should not be given any responsibility, and 60% of participants felt mentally ill people should have their own groups as healthy people should not be contaminated by them [19]. These findings illustrate just how deeply misconceptions of mental illness can be felt. Regarding late-onset psychosis, these misconceptions often influence whether a person seeks out professional, medical help, because these misconceptions are deeply rooted within them, and also may be easily contributed to old age, thus highlighting further the poor understanding of mental health issues.

Table 2: Factors influencing self-seeking behaviour.

Methodology

The Impact of Religion on Help-Seeking Behaviour in People with Serious Mental Health Illness

The environmental factors that affect the presentation and treatment of psychosis are especially important for the ethnic minority population, as often many of their environmental factors differ greatly to the white indigenous population. These patients are significantly more likely to not engage with treatment offered by mental health services and discontinue their treatment before recommended [20]. This ultimately leads to deterioration of their mental illness especially regarding psychosis and can often lead to hospital admissions. This may also explain the disproportionate number of patients from ethnic background in comparison to white patients detained under the Mental Health Act within the UK [10].

There are many additional factors that influence the ethnic communities’ lack of engagement with mental health services; however, a prominent factor appears to be their religious beliefs. The overlap between religion and psychosis/schizophrenia, both from an observational and empirical perspective has been well documented [21]. Furthermore, religion can influence both the extent of psychopathology [22] and comorbidity with substance abuse and deliberate self-harm (leading to completed suicide; [23]) in people with schizophrenia. In addition, the religious orientation (i.e., internal or external) not only influences schizotypy traits [24], but is also gender specific [25]. This finding may also provide an explanation about the psychosis gender differences in respect to prevalence rates and clinical symptomatology. Similar additional work involving people from diverse ethnic backgrounds needs to follow.

Although religion and spirituality are, at least theoretically, distinct, their distinction is often blurred since much of the completed research to date has used measures of religious practice as a proxy for spirituality [26]. It is, thus not surprising that spirituality is linked to schizotypy [27] and can also lead to so called spiritual emergencies, a biomedical discourse which constructs such experiences as psychiatric symptoms [28]. In addition, spirituality is also linked to schizophrenia, for instance, the rise of spirituality can influence the personality traits and expression of psychotic features, in many patients’ life stories, religion plays a central role in the processes of reconstructing a sense of self and recovery. However, religion may become part of the problem as well as part of the recovery. Some patients are helped by their faith community, uplifted by spiritual activities, comforted, and strengthened by their beliefs. Other patients are rejected by their faith community, burdened by spiritual activities, disappointed and demoralized by their beliefs.

Patients with ethnic backrgound undergoing treatment for schizophrenia, of whom held religious beliefs, were significantly less likely to adhere to treatments than non-religious patients [29, 30]. The reason for this may lie in both people’s strong believes that mental illness is a ‘weakness in faith’, with the illness being helped or cured through ‘willpower’ alone, as well as clergy’s perception of mental illness (‘lack of trust in God’) and their concern of mentally ill being discriminated on the base of their ethnicity and religious believes [31]. Despite this tendency among Asian and Black patients to seek mental health help from faith-based organisations, this does not appear to lead to a delay in contact with mental health services [32].

According to the 2011 census 91% (69% Christian, 15% Islam, 7 % other faiths) of the Black population and 92.38% (44% Hinduism, 22.15% Sikhism, 13.95% Islam, 12.28 other faiths) of the Indian population living within the UK are religious [33]. These religious beliefs play a large role in the recognition, treatment, and prognosis of a mental illness. For example, identifying the cause of a mental illness, using the biopsychosocial model, an intricate blend of biological (genetics, brain changes including brain chemistry and damage), social (life traumas and stresses, early life experiences and family relationships, environment) and psychological (beliefs, emotions, resilience and coping skills, and behaviour) determinants to mental health [34], helps clinicians evaluate patients and then they are able to recommend the right treatment path. However, patients with ethnic background were significantly more likely to attribute their illness to supernatural (believing in sorcery and other magico-religious phenomena, i.e., ‘someone did magic to me when I was a little boy’, ‘evil forces’) and social causes (stress, life events, social status rather than a biological or psychological problem [15].

Patients from ethnic background with strong religious beliefs are more likely to attribute their own or their family members mental illness to a spiritual battle, such as demonic forces, possession, a bad relationship with their God/Gods or sin [15]. These beliefs often lead people to seek help from leaders within their faith such as a priest, to help deliver them from their illness [35]. This can be especially troublesome, as in some religions, it can lead to exorcisms that are extremely traumatic and will more likely worsen the person’s mental state [13]. Moreover, some pastors within the Christian church take on a ‘Health and Wealth’ standpoint to their faith, which preaches if you are a true Christian, you will be always healthy and wealthy [36] This can produce feelings of inadequacy and shame which also stop people from seeking professional help for fear of being judged [37].

Although faith can extremely be comforting and can help people in a multitude of ways, the belief that mental illness is caused by a spiritual unbalance or presence stops people seeking help from medical professionals [38]. This results in a delay in treatment, especially in psychosis [37], which can be extremely detrimental to the overall prognosis of the mental illness. For patients with late-onset psychosis, these beliefs are often more archaic and include less rationality than those seen in younger generations. These beliefs are also further engrained into their lives and minds, and this makes treatment very difficult and complicated as they will often seek spiritual support rather than medical help [39]. Similar conclusions were confirmed by Codjoe et al [40], who reported that black patients emphasised the need for professionals to take their religious and cultural beliefs into account during the diagnosis and treatment of their mental health illnesses.

Stigma, racism and religion are just a few, of the many factors that influence a person’s decision to avoid seeking treatment for mental illness. When a person delays seeking medical help for psychosis, this is referred to as the duration of untreated psychosis which has been found to be a statistically significant factor in the severity of psychosis symptoms and the short- and long-term prognosis [41]. A study conducted by Addington et al [41] supported previous findings that the duration of untreated psychosis among people with ethnic background has a significant effect on the number of positive symptoms a patient experiences and found that the longer the psychosis is left untreated, the worse quality of life is for the patient. Similarly, Rapp et al [42] found that the duration of untreated psychosis was significantly associated with stronger negative symptoms and greater cognitive deficits.

Conclusion

People with psychosis from ethnic communities and indigenous white populations have distinct care pathways to care. Whereas the white population access the mental health services voluntarily via primary care setting, people with serious mental illness with ethnic extraction tend to access mental health services via secondary and secure levels of care due to emergency, coercion, compulsory admission, education and social system (if children) or legal justice system, irrespectively whether they are children [43] or adults [44]. In addition, those living in areas with residential instability are more likely to encounter a negative pathway [45]. The latest updated meta-analyses confirmed persisting, but not significantly worsening, patterns of ethnic inequalities in pathways to psychiatric care, particularly affecting Black groups [6].

These longstanding patterns of mental health access have sadly contributed to delayed diagnosis and management of many people from ethnic minorities with acute and enduring mental health diseases, and thus hindering their long-term outcomes, in terms of adequate treatment and long-term access and support to community mental health services. Although wider national campaigns both in the UK and abroad have repeatedly echoed the above findings, they sadly do not appear to connect with the ethnic communities, raising additional questions of challenging the attitudes and acceptance of mental health illness by these communities. Discrimination and a lack of access to culturally appropriate services that are cognizant of the ethnical disparities faced by these individuals [16], alongside the hampering effects of self-stigma and the perceived stigmatization by others on help (treatment)-seeking may further be augmented by their own relationships within their own ethnic groups, members of other ethnic groups and the wider society [46]. In addition, social expectations about gender, combined with racialisation and other social factors, could contribute to a negative cycle of disempowerment and stalled recovery [47]. Portraying ethnic minority people either as victims or perpetrators similarly leads to greater self-stigmatization and also triggers public stigma, in terms of generating chains of stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination.

The research to date has a number of methodological limitations, including broader categorization and heterogeneity of ethnic groups, small sample size and then predominantly involving men, as well as a limited adjustment for potential confounding factors, as discussed above, religious beliefs, economic status, cultural background, family influence etc. Furthermore, the issue of ethnic variations in pathways to psychiatric care has been studied almost exclusively within a medical epidemiological framework, and the potential insights offered by sociological and anthropological research in the fields of illness behaviour and health service use have been ignored. This has important implications as the failure of research to move beyond enumerating differences in sources of referral to psychiatric services and rates of compulsory admission means no recommendations for policy or service reform have been developed from the research [48].

Addressing the mental health needs of ethnic minorities remains one of the biggest challenges. Understanding societal and environmental backgrounds remains an unmet need that can have broader implication in both providing and accepting mental health care provision m which needs to be culturally acceptable and be societally embedded to the ethnic population. Although health inequalities are documented [49], very little is known about their real health needs and especially about their mental health when ageing. The approach ‘one hat fits all’ may not necessarily be extended to older people from ethnic minority background, as supported by the review of the literature. We need more research about their mental health to inform about any putative differences in respect to clinical phenotype(s), management, and long-term outcomes, taking into account the societal changes within this population.

Authorship Criteria

RFAG SC and EBM-L have contributed to the concept and design of the study, RG and EBM-L with acquisition and interpretation of data and drafting the article. All authors have contributed to revising the manuscript, critical evaluation of the context and have approved the final version for publication. They have all agreed EBM-L to be the corresponding author and act as the guarantor.

Conflicts of Interest/ Competing Interests

None

Acknowledgements

This work is part of MRes Thesis submitted to University of Leicester 2019 (RFAG).

We are indebted to Professor John Maltby, University of Leicester, for valuable comments on a previous draft of the manuscript.

References

- Maura, J., Weisman de Mamani A. Mental health disparities, treatment engagement, and attrition among racial/ethnic minorities with severe mental llness: A review. J Clin Psychol Med Settings. 2017; 24: 187–210.

- Myers N, Sood A, Fox KE, Wright G, Compton MT. Decision making about pathways through care for racially and ethnically diverse young adults with early psychosis. Psychiatr Serv. 2018; 70(3): 184-190.

- Lelliot P, Audini B, Duffett, R. Survey of patients from an inner-London health authority in medium secure psychiatric care. Br J Psychiatry.2001; 178(1): 62-66.

- Hunt IM, Robinson J, Bickley H, Meehan J, Parsons R, McCann K, Flynn S, Burns J, Shaw J, Kapur N, Appleby L. Suicides in ethnic minorities within 12 months of contact with mental health services. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 183: 155-160.

- McGovern D, Hemmings P, Cope R, Lowerson A. Long-term follow-up of young Afro-Caribbean Britons and white Britons with a first admission diagnosis of schizophrenia. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 1994; 29(1): 8-19.

- Halvorsrud K, Nazroo J, Otis M, Brown Hajdukova E, Bhui K. Ethnic inequalities and pathways to care in psychosis in England: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2018; 16: 223.

- Platz C, Umbricht DS, Cattapan-Ludewig K, Dvorsky D, Arbach D, Brenner, H-D, Simon AE. Help-seeking pathways in early psychosis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2006; 41(12): 967–974.

- Addington J, Van Mastrigt S, Hutchinson J, Addington D. Pathways to care: help seeking behaviour in first episode psychosis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002; 106(5): 358-364.

- Keating F, Robertson D. Fear, black people and mental illness: A vicious circle? Health Soc Care Community 2004; 12(5): 439-447.

- Gajwani R, Parsons H, Birchwood M, Singh SP. Ethnicity and detention: Are Black and minority ethnic (BME) groups disproportionately detained under the Mental Health Act 2007? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatric Epidemiol. 2016; 51(5): 703-711.

- The Mental Health Services Dataset. Detentions under the Mental Health Act. London: NHS Digital. 2019.

- Adams A, Vail L, Buckingham CD, Kidd J, Roter D. Investigating the influence of African American and African Caribbean race on primary care doctors' decision making about depression. Soc SciMed. 2013; 116: 161-168.

- Mantovani N, Pizzolati M, Edge D. Exploring the relationship between stigma and help-seeking for mental illness in African-descended faith communities in the UK. Health Expect. 2017; 20(3): 373-384.

- McGovern D, Hemmings, P.. A follow up of second generation afro-caribbeans and white british with a first admission diagnosis of schizophrenia: Attidues to mental illness and psychiatric services of patients and relatives. Soc Sci Med 1994; 38(1): 117-127.

- Mccabe R, Priebe S. Explanatory models of illness in schizophrenia: Comparison of four ethnic groups. Br J Psychiatry 2004; 185: 25-30.

- Arday J. Understanding mental health: What are the issues for Black and ethnic minority students at university? Soc Sci 2018; 7: 196.

- Baoku H. Challenging Mental Health Stigma in the Black Community. National Alliance on Mental Illness 2018.

- Roundtree PJ. (2018). Black Mental Health Matters. TedxWilmington 2018.

- The Live Love Laugh Foundation Against Depression. How India percieves mental health. 2018;

- Aggarwal NK, Pieh MC, Dixon L, Guarnaccia P, Alegria M, Lewis-Fernandez R. Clinician descriptions of communication strategies to improve treatment engagement by racial/ethnic minorities in mental health services: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2016; 99(2): 198-209.

- Grover S, Davuluri T, Chakrabarti S. Religion, spirituality, and schizophrenia: A Review. Indian J Psychol Med. 2014; 36(2): 119-124.

- Gearing RE, Alonzo D, Smolak A, McHugh K, Harmon S, Baldwin S. Association of religion with delusions and hallucinations in the context of schizophrenia: implications for engagement and adherence. Schizophr Res. 2011; 126(1-3): 150-163.

- Mohr S, Huguelet P. The relationship between schizophrenia and religion and its implications for care. SWISS MED WKLY 2004;134: 369-376.

- Maltby J, Day L: Religious experience, religious orientation and schizotypy. Ment Health Relig Cult. 2002; 5(2): 163-174.

- Maltby J, Garner I, Alan CA, Day L. Religious orientation and schizotypal traits. Pers Indivi Differ 2000; 28(1): 143-151.

- Aukst-Margetic B, Margetic B. Religiosity and health outcomes: review of literature: Coll Antropol. 2005; 29(1): 365-371.

- Willard AK, Norenzayan A. ‘‘Spiritual but not religious”: Cognition, schizotypy, and conversion in alternative beliefs. Cognition 2017; 165: 137-146.

- Kaselionyte J, Gumley A. Psychosis or spiritual emergency? A Foucauldian discourse analysis of case reports of extreme mental states in the context of meditation. Transcult Psychiatry.2019; 56(5): 1094-1115.

- Borras L, Mohr S, Brandt P-Y, Gilliéron C, Eytan A, Huguelet P. Religious beliefs in schizophrenia: Their relevance for adherence to treatment. Schizoph Bull 2007; 33(5): 1238-1246.

- Mitchell L, Romans S. Spiritual beliefs in bipolar affective disorder: their relevance for illness management. J Affect Disord. 2003; 75(3): 247-257.

- Ayvaci ER. Religious barriers to mental healthcare. Am J Psychiatry. 2016; 11: 11-13.

- Singh SP, Brown L, Winsper C, Gaiwani R, Islam Z, Jasani R, Parsons H, Rabbie-Khan F, Birchwood M. Ethnicity and pathways to care during first episode psychosis: the role of cultural illness attributions. BMC Psychiatry. 2015; 15: 287.

- Office for National Statistics. 2011 Census: Digitised Boundary Data (England and Wales) . London: UK Data Service.

- Engel GL. The need for a new medical model: A challenge for biomedicine. Science. 1977; 196: 129-136.

- Taylor RJ, Woodward AT, Chatters LM, Mattis JS, Jackson JS. Seeking help from clergy among Black Caribbeans in the United States. Race Soc Prob 2011; 3: 241-251.

- Wilson JM. From pews to polling places: Faith and politics in the American religious mosaic. Georgetown University Press, 2007.

- Edge D. ‘Why are thou cast down, o my soul?’ Exploring intersections of ethnicity, gender, depression, spirituality and implications for Black British Caribbean women’s mental health. Crit Public Health. 2013; 23(10): 39-48.

- Choudhry FR, Mani V, Ming LC, Khan TM. Beliefs and perception about mental health issues: a meta-synthesis. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016; 12: 2807–2818.

- Smolak A, Gearing R, Alonzo D, Baldwin S, Harmon S, McHugh K. Social Support and Religion: Mental Health Service Use and Treatment of Schizophrenia. Community Ment Health J. 2013; 49(4): 444-450.

- Codjoe L, Byrne M, Lister M, Mcguire P, Valmaggia,L. Exploring Perceptions of "Wellness" in Black Ethnic Minority Individuals at Risk of Developing Psychosis. Behav Cogn Psychother. 2013; 41(2):144-161.

- Addington J, Van Mastrigt S, Addington D. Duration of untreated psychosis: impact on 2-year outcome. Psychol Med. 2004; 34(2): 277-284.

- Rapp C, Studerus E, Bugra H, Aston J, Tamagni C. Walter A, Pflueger M, Borgwardt S, Riecher-Rossler A. Duration of untreated psychosis and cognitive functioning. Schizophr Res 2013; 145(1-3): 43-49.

- Edbrooke-Childs J, Newman R, Fleming I, Deughton J, Wolpert M. The association between ethnicity and care pathway for children with emotional problems in routinely collected child and adolescent mental health services data. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016; 25(5): 539–546.

- Bhui K, Stansfeld S, Hull S, Priebe S. Ethnic variations in pathways to and use of specialist mental health services in the UK: Systematic review. Br J Psychiatry 2003; 182: 105-116.

- Rotenberg M, Tuck A, Ptashny R, McKenzie K. The role of ethnicity in pathways to emergency psychiatric services for clients with psychosis. BMC Psychiatry. 2017; 17(1): 137.

- Cheng HL, Kwan KL, Sevig T. Racial and ethnic minority college students' stigma associated with seeking psychological help: Examining psychocultural correlates. J Couns Psychol. 2013; 60(1): 98-111.

- Robinson M, Keating F, Robertson S. Ethnicity, gender and mental health. Diversity in Health Care. 2011; 8(2): 81-92.

- Morgan C, Mallett R, Hutchinson G, Leff J. Negative pathways to psychiatric care and ethnicity: The bridge between social science and psychiatry. Soc Sci Med. 2004; 58(4): 739-752.

- The King’s Fund. The health of people from ethnic minority groups in England, 2021.