The Case for Using Patient Reported Outcome Measure (Prom) To Improve Health Related Quality Of Life (Hrqol)

Menon M1 and George B2*

1Chief Information Officer, Spotcheck Global, UAE

2Christian Brothers University, Memphis, TN, USA

Received Date: 12/09/2020; Published Date: 09/10/2020

*Corresponding author:Babu George, Professor, Christian Brothers University, Memphis, TN, USA. E-mail: bgeorge@cbu.edu

Abstract

Patient-reported outcomes measures (PROMs) are a critical element of assessing whether clinicians are improving the health of patients (Black, 2013). Unlike other process measures, which capture provider efficiency and adherence to the standards of recommended care, or patient experience measures, which focus on aspects of care delivery such as communication (Doward & McKenna, 2004). PROMs endeavor to capture whether the services provided actually improved patients' health and sense of well-being. Patients are enquired to assess their general health, ability to complete various activities, mood, level of fatigue, and pain. In coming years, PROMs are expected to play a more noticeable role in evaluating performance and determining the comparative effectiveness of different treatments. This paper proposes a methodology for implementing this solution.

Keywords: Outcome Measure; Health Quality; Quality of Life; Perception; SF-36

Introduction

PROMs are typically self-reported questionnaires, which can be completed by the patients themselves or others on their behalf easily [1]. There are increasing attempts to quantify outcome measures by patients. Assessment of outcomes based on PROMs are increasingly accompanying traditional clinical measures of health care outcomes. Furthermore, for more than a decade, PROMs have played and continue to play a pivotal role in academic and clinical research, resulting in the development of many thousands of reliable and valid instruments to measure recipients’ self-reported health. Many studies had been conducted across the globe to develop PROM frameworks for various diseases conditions like diabetes prove conclusively that localization of clinical, socio-economic, and behavioral knowledge is one of the key determinants of better outcomes [2].

Access to the patients’ perspective through the use of PROMs can impact comprehensive range of issues pertaining to the delivery of healthcare including identification those issues faced by patients and their families living with an illness, treatment decisions and adherence, and better understanding as to how health-practitioners can positively impact healthcare outcomes. Patient Reported Outcome Measures can help gain insight from the perspective of the patient about the impact of the disease and its treatment on their lifestyle. Subsequently, this improves the patient’s health related quality of life (HRQoL), which the degree to which the treatment and the disease as perceived by the patient to impact on those aspects of their life related to life which are considered important [3].

The Methodology

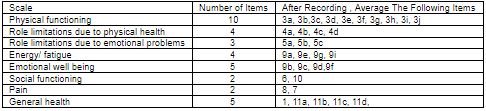

The SF-36, a multi-purpose, short-form health survey with only 36 questions could be tweaked to gather the PROM data in different sub-contexts [4]. This instrument yields an 8-scale profile of functional health and well-being scores as well as psychometrically based physical and mental health summary measures and a preference-based health utility index.

The SF 36 questionnaire has items grouped in 8 domains and a single question on change in health during preceding year. Domains measured are:

- Physical Functioning-10 items

- Social Functioning-2 items

- Physical Role limitations-4 items

- Emotional role limitation-3 items

- Mental health-5 items

- Energy / Vitality-4 items

- Bodily Pain-2 items

- General Health Perception- 5 items

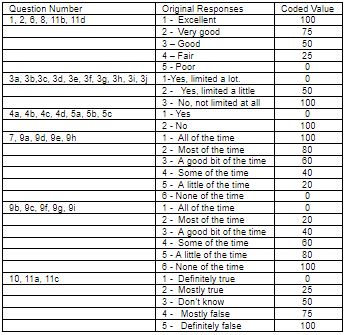

All questions are scored on a scale from 0 to 100, with 100 representing the highest level of functioning possible. Aggregate scores could be compiled as a percentage of the total points possible, using the scoring table. For more information, kindly see Tables 1 and 2 given below.

The scores from those questions that address each specific area of functional health status will be then averaged together, for a final score within each of the 8 dimensions measured. (e.g. pain, physical functioning etc.) For example, to measure the patients energy/fatigue level, add the scores from questions 9a, 9e, 9g and 9i. If a patient circled 4 on 9a, 3 on 9e, 3 on 9g and left 9i blank, use table 1 to score them.

An answer of 4 to 9a is scored as 40, 3 to 9e is scored as 60, and 3 to 9g is scored as 40.9i is omitted. The score for this block is 40+60+40 =140. Now we divide by the 3 answered questions to get a total of 46.7. Since a score of 100 represents high energy with no fatigue, the lower score of 46.7% suggests the patient is experiencing a loss of energy and is experiencing some fatigue. All 8 categories are scored in the same way. Using this questionnaire at the beginning and during the course of care, we can track the progress of the 8 parameters.

The preferred method would be computerized (website) questionnaire administration, where the items are presented on the computer. Others option would be:

- Face-to-face questionnaire administration, where an interviewer presents the items orally.

- Paper-and-pencil questionnaire administration, where the items are presented on paper.

Patients will be asked to self-complete the questionnaires without assistance. Evidence suggests that interviewer-administered questionnaires are associated with a range of response biases and so should not be employed. Similarly, the ad hoc translation of the questionnaires by, for example, local translators, relatives is not acceptable for technical reasons.

The PROMs used to collect data from patients will comprise a condition-specific instrument and/or a generic instrument, in addition to more general patient-specific information. The patient-specific questions comprise socio-demographic questions and questions about the patient’s general health, previous surgery for the target condition, co-morbidities and length of time with the condition.

Medical records review for lab and radiology reports could be used to estimate clinical outcome and measures. When it comes to the types of outcome measurements, the data would be in two sets. The first set of data could be taken from the clinician perspective about patient and the treatment provided. This data would be obtained from secondary data sources – medical records of the same group of patients. Then, patients could be interviewed for the second set of data – patient reported outcomes. From the group of patients, selected by using the sampling plans and procedures, the data pertaining to the study variables i.e., related to the treatment received, socio-economic, physiological, psychological could be collected and tabulated.

The SF 36 is a generic measure, as opposed to one that targets a specific age, disease, or treatment group. Accordingly, the SF-36 has proven useful in surveys of general and specific populations, comparing the relative burden of diseases, and in differentiating the health benefits produced by a wide range of different treatments.

Previous Studies

Thirty-nine studies were identified supporting the use of the SF-36 with patients undergoing elective coronary procedures; of these, eight studies were carried out in the UK [5-9]. Thirty studies examined outcomes in CABG patients, 13 were concerned with outcomes of PCI; four studies examined both CABG and PCI.

About half of the studies were published in the last five years. Internal consistency reliability of the SF-36 was supported with Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.73 (GH) to 0.90 (PF) in a large study of patients undergoing CABG and/or valve surgery [10]. Similar values were found in a study comparing generic and specific measures for measuring HRQoL after PCI [11]. Cronbach’s alpha exceeded 0.85 for all subscales in a study comparing outcomes following coronary stenting versus balloon angioplasty [12], ranged 0.80- 0.94 in the Stent-PAMI trial [11], and exceeded 0.80 in a postal survey assessing QoL in women after either an acute cardiac event or CABG [13]. Good internal consistency was also reported in a study examining differences in recovery outcomes for two groups of older adults undergoing Cardiac Rehabilitation (CR) post-CABG [14], with high alpha coefficients of 0.84 (pre-test) and 0.81 (post-test) for the PCS, and 0.86 (pre-test) and 0.84 (post-test) for the MCS. High Cronbach’s alpha values in six of the domains (0.82 and above) were reported in a postal survey of post-CABG patients undergoing CR [15]. The PF subscale correlated strongly with the CCS classification in the 1997 study by [12], supporting construct validity of the measure. Construct validity of the SF-36 was further supported by strong correlation of the PCS (0.65) with the EQ-VAS in a study of long-term survival post-CABG [16]; however, correlation between the MCS and the EQ-VAS was weaker (0.48) [16-19].

Table 1: SF-36 Scoring method.

Table 2: SF 36 Domains and associated question numbers.

Conclusion

Lack of the care receiver engagement and involvement in key decision-making and a general failure to design care delivery processes around the needs of the care receivers have been accepted as some of the big challenges in health care delivery. Care receivers are now more informed, capable of understanding complex health care issues, and making appropriate decisions about the care they receive. The Internet has succeeded in making available a large volume of clinical and general medical information to care receivers that have played a prominent role in this transformation. Such a trove of information could be leveraged to improve HRQoL by better coupling it with the PROM data gathered from each patient. Much of these processes could be automated with the help of AI and machine learning systems.

References:

- Branski RC, Cukier-Blaj S, Pusic A, Cano SJ, Klassen A, Mener D, Kraus DH. Measuring quality of life in dysphonic patients: a systematic review of content development in patient-reported outcomes measures. Journal of voice. 2010;24:193-198.

- Patel DP, Elliott SP, Stoffel JT, Brant WO, Hotaling JM, Myers JB. Patient reported outcomes measures in neurogenic bladder and bowel: a systematic review of the current literature. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2016;35:8-14.

- Davies M, Speight J. Patient-reported outcomes in trials of incretin-based therapies in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes, Obesity and Metabolism. 2012;14:882-892.

- Lins L, Carvalho FM. SF-36 total score as a single measure of health-related quality of life: Scoping review. SAGE open medicine. 2016;4:2050312116671725.

- Ascione R, Reeves BC, Taylor FC, Seehra HK, Angelini GD. Beating heart against cardioplegic arrest studies (BHACAS 1 and 2): quality of life at mid-term follow-up in two randomised controlled trials. European heart journal. 2004;25:765-770.

- Edwards H, Courtney M, Finlayson K, Shuter P, Lindsay E. A randomised controlled trial of a community nursing intervention: improved quality of life and healing for clients with chronic leg ulcers. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2009;18:1541-1549.

- Lee LC, Harrington RA, Louie BB, Newschaffer CJ. Children with autism: Quality of life and parental concerns. Journal of autism and developmental disorders. 2008;38:1147-1160.

- Schroter S, Lamping DL. Responsiveness of the coronary revascularisation outcome questionnaire compared with the SF-36 and Seattle Angina Questionnaire. Quality of life Research. 2006;15:1069-1078.

- Wyatt G, Sikorskii A, Tamkus D, You M. Quality of life among advanced breast cancer patients with and without distant metastasis. European journal of cancer care. 2013;22:272-280.

- McCarthy Jr MJ, Shroyer AL, Sethi GK, Moritz TE, Henderson WG, Grover FL, et al. Self-report measures for assessing treatment outcomes in cardiac surgery patients. Medical care. 1995;OS76-OS85.

- Rinfret S, Grines CL, Cosgrove RS, Ho KK, Cox DA, Brodie BR, Stent-PAMI Investigators. Quality of life after balloon angioplasty or stenting for acute myocardial infarction: one-year results from the Stent-PAMI trial. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001;38:1614-1621.

- Krumholz HM, Cohen DJ, Williams C, Baim DS, Brinker J, Cabin HS, et al. Health after coronary stenting or balloon angioplasty: results from the Stent Restenosis Study. American heart journal. 1997;134:337-344.

- Worcester MUC, Murphy BM, Elliott PC, Le Grande MR, Higgins RO, Goble AJ, Roberts SB. Trajectories of recovery of quality of life in women after an acute cardiac event. British journal of health psychology. 2007;12:1-15.

- Dolansky MA, Moore SM. Effects of cardiac rehabilitation on the recovery outcomes of older adults after coronary artery bypass surgery. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2004;24:236-244.

- Hawkes AL, Nowak M, Speare R. Short Form-36 Health Survey as an evaluation tool for cardiac rehabilitation programs: is it appropriate?. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2003;23:22-25.

- Bradshaw PJ, Jamrozik KD, Gilfillan IS, Thompson PL. Asymptomatic long-term survivors of coronary artery bypass surgery enjoy a quality of life equal to the general population. American heart journal. 2006;151:537-544.

- Anthoine E, Moret L, Regnault A, Sébille V, Hardouin JB. Sample size used to validate a scale: a review of publications on newly-developed patient reported outcomes measures. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2014;12:1-10.

- Black N. Patient reported outcome measures could help transform healthcare. Bmj. 2013;346:29-37.

- Doward LC, McKenna SP. Defining patient-reported outcomes. Value in health. 2004;7:S4-S8.