Evaluating the Outcome of Pretreatment with Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GnRH)Antagonist on Poor Responders Receiving a Flexible GnRH Antagonist Protocol for Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection: A Randomized Clinical Trial

Fatemeh K1, Hossein-Rashidi B2, Tarafdari-Manshadi A1, Farajzadeh-Vajari F3* and Molaei H4

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2Valiasr Reproductive Health Research Center, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

3Resident in IVF Fellowship, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

4Department of Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery, Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex (IKHC), Tehran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Received Date: 14/08/2020; Published Date: 31/08/2020

*Corresponding author: Fatemeh Farajzadeh-Vajari, Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex (IKHC), Bagherkhan st. Towhid Sq., Tehran, Iran. Fax:+98-21-6119-2386 ; Tel: +98-21-6119-2386 ; Mobile: +98-911-194-0477 ; Email: fatemeh_582003@yahoo.com; ORCID: 0000-0002-8535-405

Abstract

Purpose: There are many protocols for ovarian stimulationin poor responders. We evaluated the outcome of a pretreatment with gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) antagonist on poor responders who were undergoing a flexible GnRHantagonist protocol.

Methods and Materials: In a randomized controlled clinical trial,we divided 66 women who were poorly responding to treatment into two groups: 1) pretreatment and2) control groups. In the control group, we did the ovarian stimulation from the second day of the cycle and treatment continued based on the flexible GnRH antagonist protocol. In the pretreatment group, we administered GnRH antagonist (cetrotide) from the second day of the cycle for three consecutive days. Then the flexible antagonist protocol began same as the control group. The main outcome measures were cumulous oocyte complex, metaphase II (MII) oocyte,and embryo number.The secondary outcome measure waschemical pregnancy.

Results: There were no significant differencesregarding demographic featuresand the main treatment protocols between the two groups. The means of mature oocytes (48.5 % vs 30.3%) and embryoswith more than three MⅠⅠoocytes (27.3%vs 29.2%) were higherin the pretreatment group, but not significantly different. Meansof serum estradiol (7.6 vs 1.1) and progesterone (1.1 vs 0.7) on the trigger day were significantly higher in the control group.

Conclusion: Doing a pretreatment with GnRH antagonist can result in more follicles, oocytes and embryos, although the differencemight not be significant.

Keywords: Poor Responder; Pretreatment; Gnrh Antagonist; Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection

Introduction

Assisted reproduction treatment (ART) has been developing in the recent decades. It has led to better outcomes and more fertilities that are successfulin a short time. The possibility of resolving infertility and ovarian response to ART has increased even in older women who have less ovarian reserve [1]. Women who undergo ART are categorized into three groups: high, normal and poor responders. This is based on many factors, including age, body mass index, anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH), antral follicle count, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), and ovarian volume. In poor responders, achieving a good response and high number of oocytes are important for a better outcome. Researchers have explained different protocols to improve the ovarian response in poor responders, including using high gonadotropin and pretreatment with oral contraceptive pills, estrogen priming and long protocol with microdose gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist. None of these protocols has an effect on live birth rate in poor responders and they mostly increase the oocyte number in the treatment cycle [2, 3].

In ovarian stimulation, gonadotropin consumption induces multi-ovarian follicular growth.The increase in endogenous FSH levels at the end of the luteal phase occurs due to the regression of the corpus luteum and the decrease in estrogen production. This results in the growth of follicles that do not grow at the same time as the follicles that have grown since the beginning of the cycle [4, 5]. In the flexible GnRH antagonist regimen, the prescribed gonadotropin stimulates ovarian follicles on the second and third days of the menstrual cycle. Moreover, increased interphase FSH level leads to another follicular recruitment. Thus, after human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) injection, some growing follicles appear which are not synchronized with the developed follicles. That means by suppression of raised interphase FSH level, exogenous gonadotropin is the only follicle stimulation source that make synchronous follicles [8]. Less number of oocytes and embryos are an important characteristic of GnRH antagonist protocol compared to the long GnRH agonist protocol [6, 7]. GnRH antagonist is a common protocol, but asynchronization is its drawback. Some methods have been suggested to enhance follicular synchronization in GNRH antagonist cycles, including pretreatment with estrogen in the luteal phase, taking oral contraceptive pills, and starting GnRH antagonist earlier [9]. In this study, we evaluated the outcome of pretreatment with GnRH antagonist on poor responders who underwent treatment with the flexible GnRH antagonist protocol. The aim was to find out whether this method leads to increased follicular synchronization and mature oocytes or not.

Methods and Materials

In this randomized clinical trial, we studied 66 poor responding women who were in an ART program between August 2019 and January 2020. They were randomly divided into two groups (n = 33 for each group): 1) pretreatment and 2) control groups. We had defined poorly responding to treatment based on the patient–oriented strategies encompassing individualized oocyte number (POSIDONE) criteria (groups 3 and 4). The POSEIDON criteria has four groups. The first group is defined as being younger than 35 years old, having AMH ≥1.2, antral follicle number ≥5, and unexpected poor or suboptimal ovarian response. The second group is defined as being older than≥35 years old, having AMH ≥ 1.2, antral follicle number ≥5, and unexpected poor or suboptimal ovarian response. The third group is defined as being younger than 35 years old, having AMH ≤1.2, and antral follicle number ≤5. The fourth group is defined as being older than 35 years old, having AMH ≤1.2, and antral follicle number ≤5. All patients signed an informed consent before entering the study. Demographic and clinical characteristics, such as age, weight and height were collected. We had arranged to compare two treatment protocols for ovarian stimulation on poorly responding patients.

In the control group, we used a flexible GnRH antagonist protocol. It started from the second day of the cycle with r FSH+human menopausal gonadotropin (HMG) (300 units) and GnRH antagonist (Cetrotide, Mreck Serono, Germany 0.25 mg) prescribed when follicle size was ˃13 mm and hCG (5000 units) was injected when follicle size was > 18 mm.Afterwards, oocyte puncture was planned 36 hours after hCG injection. In the pretreatment group, we administered GnRH antagonist (cetrotide) for three consecutive days from the second day of the cycle and then we did the ovarian stimulation with flexible GnRH antagonist protocol from the third day of the cycle. The inclusion criteria (based on POSIDONE) were: 1) being younger than 40 years old; 2) having AMH < 1.2; and 3) antral follicle count < 5 in ovaries based on the vaginal ultrasound imaging. The onco-fertility patients and women older than 40 years old were excluded from the study. The main outcome measures were cumulous oocyte complex, metaphase II (MII) oocyte, embryo number. The secondary outcome measures were positive hCG and chemical pregnancy. The ethics committee of our university approved this study (IRCT20190602043792N1).

Statistical Analysis

We considered the number of cumulous oocyte complex as a dependent variable and body mass index, antral follicle count, kind of infertility (unexplained, male factor, tubal factor, and ovarian factor), pretreatment and control groups as independent variables. We gathered all data in questionnaires. Associations between categorical variables were tested with chi-square analysis or Fisher’s exact test. Difference between the two arms was assessed with 95% confidence interval and Pvalue. We did the data analysis with the statistical package for social science (SPSS) version 22. Pvalue less than 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

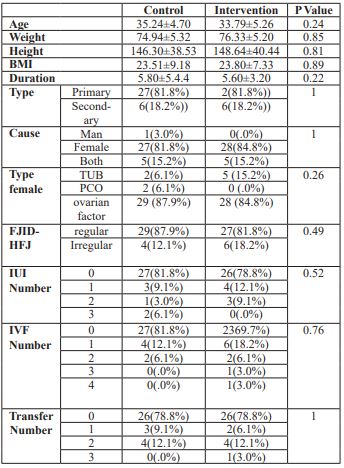

There were no differences in terms of AMH(0.61 ng/dl vs 0.64 ng/dl),body mass index (23.5 kg/m2 vs 23.7 kg/m2) and age(35.2 vs 35.7 years old) between the two groups (Table1).Threewomen (9.1%) in the pretreatment group and one woman (3%) in the control group did not respond to ovarian stimulation and had no follicular growth.Eight women in the pretreatment group (24.2%) and seven women (21.2%) in the control group had no oocytes after ovarian puncture. 10 women (30.3%) in the pretreatment group and 15 women (45.5%) in the control group had 1-2 oocytes.

Table 1: Demographic features of control and interventional groups

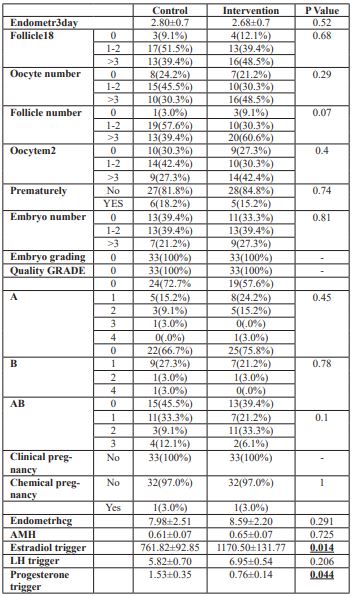

The mean of embryos with more than three oocytes was higher in the pretreatment group compared to the control group (P value: 48.5% vs 30.3%). However, the difference was not significant. 11 women (33.3%) in the pretreatment group and 13women (39.4%) in control group had no embryo development. The mean of embryos more than three was higher in intervention group compared to the control group (nine patients 27.3% vs seven patients 29.2%).However, none of these differences was significant. There was no significant difference between the two groups based on embryo grading. There was no significant difference regarding premature luteinizing hormone surge between the pretreatment and control groups (five(15%) vs six(18%), respectively). The means of follicles, oocytes and embryos were higher in the pretreatment group compared to the case group, but it was not significantly different. However, the meansof serum estradiol (7.6 vs 1.1) and progesterone (1.1 vs 0.7) on the trigger day were significantly higher in the control group compared to the pretreatment group (Table 2).

Table 2: IVF outcome among interventional and control group.

We froze the embryos for most patients because of embryo banking.Fresh embryo transfer was done only in twowomen of both groups.There was no differences in chemical pregnancy rateswithin both group (33%vs 33%).

Discussion

Poor responders need better treatment protocols to achieve more success. Therefore, there are many researches on various treatment protocols. Fanchin et al explored the use of serum estradiol during the luteal–follicular phase to inhibitFSH increase. They showed that increased follicular synchronization results in more saved mature oocytes [10]. Cédrin-Durnerin et al studied 427 patients in two groups: pretreatment with estradiol and control group with GnRH antagonist protocol. Their finds were not consistent with Fanchin et al about enhanced mature oocytes with pretreatment [11]. Rombauts et al assessed the use of oral contraceptives before GnRH antagonist protocol. They found out that the number of oocytes was similar to GnRH antagonist protocol without contraceptives. They stated that we can use oral contraceptives before stimulation to schedule patients [12]. Pretreatment with oral contraceptivedelays ovarian stimulation, but pretreatment with GnRH antagonist can be used without any stimulation delay. Kolbianakis et al suggested that we could achieve similar outcomes with oral contraceptives [13]. However, in a meta-analysis on oral contraceptive pretreatment, Smulders et al concluded that this results in significant decrease in clinical pregnancy rate [20].

In a retrospective study, Park et al introduced early GnRH antagonist as a pretreatment in GnRH antagonistprotocol. This resulted in increased mature oocytes compared to conventional GnRH antagonist protocol and enhanced synchronization resulted in improved pregnancy rate [15]. Their results are in agreement with ours. In 2012, Viardot-Foucault et al did a similar randomized clinical trial on normal responders in Singapore. They stated that live birth and clinical pregnancy rates are not significantly different between GnRH antagonist groups with or without pretreatment [16]. However, we did not gather data on live birth rates. In a similar randomized controlled trial on 69 patients, Blockeel et al evaluated the administration of GnRH antagonist for three days before GnRH antagonist protocol as pretreatment. They observed no significant impact on the ongoing pregnancy, but there were higher oocytes [17]. We obtained higher oocyte number and embryo in the pretreatment group compared to the control group, although it was not significant.

Frankfurter et al studied a series of poor responding cases with a new protocol. They used GnRH antagonist on cycle days 5-8 and four days after the initial GnRH antagonist injection. They compared the results of their protocol with a control group that underwent the conventional GnRH antagonist and found higher oocytes, embryos and pregnancy rates in the intervention group [18]. We did the pretreatment for three consecutive days before the main treatment. However, Frankfurter et al did it twice: days 5-8 of the cycle and after the initial GnRH antagonist injection. Their results were same as ours, although we acquired this outcome with less GnRH antagonist dosages. Bukulmez et al reported on using GnRH antagonist before the beginning of the conventional GnRH antagonist compared to the long protocol.They stated that there is less embryo development and blastulation compared to the long protocol [19]. However, we compared pretreatment GnRH antagonist with the conventional GnRH antagonist protocol.

Eftekhar et al evaluated using GnRH antagonist as a pretreatment in a GnRH antagonist protocol for patients with polycystic ovary syndrome undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF)/ intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) cycles. They found greater number of M ocytes and embryos and higher clinical pregnancy rates [20]. In their study, GnRH antagonist protocol started on the second day of the menstruation cycle. Increased follicular synchronization and mature oocyte was observed in the pretreatment group compared to the flexible GnRH antagonist in high responding patients. However, we compared the results of the pretreatment with GnRH antagonist in a flexible GnRH antagonist protocol with a control group in poor responders. Obviously, there are less follicles in the ultrasound imaging results of poor responders on the second day of the cycle compared to the high responders. Therefore, it is important to assess the impact of pretreatment with GnRH antagonist on increase of follicles and mature oocytes in poor responders.

Coordinating the growth of follicles increases the alignment of the follicles during their puncture. We found higher number of follicles, oocytes and embryos in the pretreatment group compared to the control group, but it was not significantly different. The level of serum estradiol and progesterone was significantly higher on the trigger day in the control group, which could because of suboptimal reproduction outcome in this group. Since we did this study with fewer cases in a short period, we did not compare pregnancy and live birth rates. Our patients mostly had frozen embryo scheduled for banking. This protocol (pretreatment + conventional GnRH) has advantages compared to other pretreatment strategies for poor responders. Pretreatment with GnRH antagonist can start during the ongoing menstrual cycle without waiting for the next cycle and may prevent premature luteinizing hormone surge. The limitations of our study were its low number of cases and short investigation period.

Conclusion

Pretreatment with GnRH antagonist can cause synchronization of follicles with suppression of FSH interphase and established more oocytes and embryo. This is important for poor responders. Successful pregnancy and live birth rates are associated with other factors that require further research. Doing the same study with a larger sample size is recommended.

Acknowledgment

The authors appreciate the support and constructive comments of the methodologist of the research development office at Imam Khomeini Hospital Complex, Tehran, Iran. The authors thank Muhammed Hussein Mousavinasab for editing this text.

Ethical Approval

The ethics committee of our university has approved this study (IRCT20190602043792N1).

Conflict of Interest

None

Funding

None

Informed Consent

All the patients signed informed consents.

References:

- Polyzos NP1, Blockeel C, Verpoest W, De Vos M, Stoop D, Vloeberghs V, Camus M, Devroey P, Tournaye H. Live birth rates following natural cycle IVF in women with poor ovarian response according to the Bologna criteria Hum Reprod. 2012;27(12):3481-6.

- Berkanoglu M, Ozgur K. What is the optimum maximal gonadotropin dosage used in micro dose flare – up cycles in poor responders? Fertil Steril. 2010;94:662-5.

- Lefebvre J, Antaki R; Kadoch IJ, Dean NL, sylvestre C, Bissonnette F, Benoit J, Menard S, lapensee L.450IU versus 600IU gonadotropin for controlled ovarian stimulation in poor responder: A randomized controlled trial. Fertil Steril. 2015;104:1419-25.

- Roseff SJ, Bangah ML, Kettel LM, Vale W, Rivier J, Burger HG, et al. Dynamic changes in circulating inhibin levels during the luteal follicular transition of the human menstrual cycle. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1989;69:1033-9.

- Hall JE, Schoenfeld DA, Martin KA, Crowley WF Jr. Hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion and follicle-stimulating hormone dynamics during the luteal-follicular transition. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1992;74:600-7.

- Al-Inany HG1, Youssef MA, Aboulghar M, Broekmans F, Sterrenburg M, Smit J, Abou-Setta AM Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone antagonists for assisted reproductive technology. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;1(5):CD001750

- Scott RT, Navot D. Enhancement of ovarian responsiveness with microdose of gonadotropin – releasing hormone agonist during ovulation induction for in nitro fertilization. Fertil Steril. 1994;61(5):880 -5.

- Kolibianakis EM, Collins J, Tarlatzis BC, Devroey P, Diedrich K , Griesinger G. Among patients treated for IVF with gonadotrophins and GnRH analogues, is the probability of live birth dependent on the type of analogue used? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Hum Reprod Update. 2006;12:651-71.

- Fanchine R ,Salomon L ,Casstelo- Branco A ,Olivennes F ,Frydman N ,Frydman R. Luteal estradiol pre –treatment coordinates follicular growth during controlled ovarian hyper stimulation with GNRH antagonist. Hum Reprod. 2003;18:2698-703

- Fanchin R, Cunha-Filho JS, Schonäuer LM, Kadoch IJ, Cohen-Bacri P, Frydman R. Coordination of early antral follicles by luteal estradiol administration provides a basis for alternative controlled ovarian hyperstimulation regimens. Fertil Steril. 2003;79(2):316-21.

- Cédrin-Durnerin I1, Guivarc'h-Levêque A, Hugues JN; Groupe d'Etude en Médecine et Endocrinologie de la Reproduction Pretreatment with estrogen does not affect IVF-ICSI cycle outcome compared with no pretreatment in GnRH antagonist protocol: a prospective randomized trial. Fertil Steril. 2012;97(6):1359-64.e1

- Rombauts L ,Healy D, Rob J ,A comparative randomized trial to assess the impact of oral contraceptive pretreatment on follicular growth and hormone profiles in GNRH antagonist – treated patients. Hum Reprod. 2006;21(1):95-103.

- Kolbianakis EM, Papanikolaou, EG.Camus M, Tournaye H, Van Steirteghem AC, Devroey P. Effect of oral contraceptive pill pre- treatment on ongoing pregnancy rates in patients stimulated with GNRH antagonist and recombinant FSH for IVF. A randomized controlled trial . Hum Reprod. 2006;21(2):352-7. Epub 2005 Nov 3.

- Smulders B, Van Oirschot S.M, Farquhar C, Rombauts L, Kremer J.A. Oral contraceptive pill, progestogen or estrogen pre-treatment for ovarian stimulation protocols for women undergoing assisted reproductive techniques. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2010; (Issue; CD006109).

- Park CW, Hwang YI, Koo HS, Kang IS, Yang KM, Song IO. Early gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist start improves follicular synchronization and pregnancy outcome as compared to the conventional antagonist protocol. Clin Exp Reprod Med. 2014;41(4):158-64

- Viardot-Foucault V, Nadarajah S, Lye WK, Tan HH. GnRH antagonist pre-treatment: one centre's experience for IVF-ICSI cycle scheduling. Reprod Biomed Online. 2015;30(4):366-72

- Blockeel C, Riva A, De Vos M, Haentjens P, Devroey P. Administration of a gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist during the 3 days before the initiation of the in vitro fertilization/intracytoplasmic sperm injection treatment cycle: impact on ovarian stimulation. A pilot study. Fertil Steril. 2011;95(5):1714-9.e1-2. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2011.01.028.

- Frankfurter D1, Dayal M, Dubey A, Peak D, Gindoff P. Novel follicular-phase gonadotropin-releasing hormone antagonist stimulation protocol for in vitro fertilization in the poor responder Fertil Steril. 2007;88(5):1442-5. Epub 2007 May 4.

- Bukulmez O ,Rehman KS ,Langley M ,Carr BR, Nackley AC. Doody KM ,et al . Precycle administration of GnRH antagonist and microdose HCG decreases clinical pregnancy rates without affecting embryo quality and blastulation.” Reproductive biomedicine online. 2006:13940;465-75.

- Eftekhar M , Bagheri RB, Neghab N, Hosseinisadat R. Evaluation of pretreatment with Cetrotide in an antagonist protocol for patients with PCOS undergoing IVF/ICSI cycles : a randomized clinical trial, JBRA Assisted Reproduction. 2018;22(3):238-243.