Profile of Dentistry Graduates and Their Integration into the Job Market

Rosa Ines Barbosa1, Rafaela Costa Mariano Faria1, Hertha Dadério Corrêa Lima1, Célio dos Santos Silva1, Fernanda Calvo Costa1,*, João Maurício Ferraz da Silva2, Eduardo Galera da Silva3, Rubens Nisie Tango2 and Ana Paula Martins Gomes4

1Master's Program in Science and Technology applied to Dentistry of the São Paulo State University (UNESP), Institute of Science and Technology, São José dos Campos, Brazil

2Department of Dental Materials and Prosthesis, Professor of the Post-Graduation Program of Science and Technology Applied to Dentistry of the São Paulo State University (UNESP), Institute of Science and Technology, São José dos Campos, Brazil

3Department of Social Dentistry and Pediatric Clinic, Professor of the Post-Graduation Program of Science and Technology Applied to Dentistry of the São Paulo State University (UNESP), Institute of Science and Technology, São José dos Campos, Brazil

4Department of Restorative Dentistry, Professor of the Post-Graduation Program of Science and Technology Applied to Dentistry of the São Paulo State University (UNESP), Institute of Science and Technology, São José dos Campos, Brazil

Received Date: 25/03/2025; Published Date: 09/05/2025

*Corresponding author: Fernanda Calvo Costa, DDs., Master's Program in Science and Technology applied to Dentistry of the São Paulo State University (UNESP), Institute of Science and Technology, São José dos Campos, Brazil

Abstract

Dentistry has undergone significant changes in recent years due to the increase in the number of professionals in the field and the transformations in the job market, demanding graduates to adapt to the new reality of the profession. Given Brazil's economic instability, many dental professionals seek stable jobs, such as in the public sector, aiming for financial security. However, these sectors offer a limited number of positions nationwide. In the private sector, it is evident that the exponential increase of new dentists each year has led to a supersaturated market with professionals, sometimes highly specialized, seeking alternatives to boost their income. Currently, dental surgeons are seeking new strategies to position themselves in the job market to achieve successful outcomes in their practices. Thus, the objective of this study was to evaluate the profile of graduates from a Faculty of Dentistry in the State of São Paulo and their integration into the job market, aiming at understanding this new professional scenery and its relationship with professional training.

Keywords: Dental Education; Dental Staff; Dentistry; Health Personnel; Job Market

Introduction

The first higher education course of Dentistry in Brazil was recognized in 1884 through the Decree 9,311 from October 25 [1]. In 1911, the first technical chair in Dentistry was created, and only in 1915 did the curriculum began to include "Dental Techniques" – exercises on mannequins – and "Dental Clinic" – patient care. This new format provided a more comprehensive education for students, better aligned to the population's needs at the time [2].

Following the restriction of dental practice to only certified dental surgeons in 1932 and the growing supply and demand for health services, Dentistry experienced decades of significant technical and scientific development, gaining considerable social prestige, which positively impacted the income and satisfaction of its professionals, with its "golden decade" between the 1960s and 1980s [3].

As the private sector job market grew and consolidated, the need for dentists to stand out among their peers by offering increasingly specialized services became urgent, making their practice excessively technical [4,5]. On the other hand, the public sector implemented the Unified Health System (SUS) in 1990, which integrated Dentistry in 2004 [4]. This integration of Dentistry into SUS expanded the range of opportunities for professionals in the field, focusing their practice on public health in line with the New National Curriculum Guidelines (2002). The goal was to provide a "generalist, humanistic, critical, and reflective education to work at all levels of health care (...) based on ethical and legal principles and understanding the social, cultural, and economic reality, directing their practice towards transforming the reality for the benefit of society" [2,5,6]. Two parallels, therefore, had been established within the dental practice.

Over the years, the economic instability in Brazil, combined with the exponential increase of new dentists every year, created a saturated market with professionals seeking alternatives to increase their income. The public sector has a limited number of job positions, and in private clinics and offices, technical specialization no longer guarantees differentiation [3,8,9]. Dental surgeons are now seeking new strategies to stay in the market, looking for knowledge in entrepreneurship, management, and marketing. Additionally, a considerable portion of professionals indirectly have become salaried through partnerships with health insurance companies and dental plans [3,7,9,10].

Given this scenario, the search for new opportunities has expanded the field for dental professionals: industry, commerce, and even startups integrating technology into clinical practices are examples of sectors currently employing dental surgeons. Furthermore, the emergence of new fields such as orofacial harmonization and the incorporation of promising technologies from digital workflows have led to a new transformation in the dental scenario. To better understand this new scenario, it is necessary to fully understand the practices, impressions, and aspirations of active professionals, making it possible to understand not only current Dentistry but also the future directions of the profession [11,12,133]. Thus, the objective of this study was to evaluate the profile of graduates from a Faculty of Dentistry in the State of São Paulo and their integration into the job market, aiming at understanding this new professional scenario and its relationship with professional training.

Material and Methods

This Research Project was submitted and approved by the Research Ethics Committee with Human Beings of ICT/SJC – UNESP (CAAE: 58828322.5.0000.0077). This study is characterized as observational and descriptive, conducted using a quantitative method. The study evaluated graduates from the Dentistry Course at the Institute of Science and Technology of São José dos Campos - UNESP, who have graduated between 2002 and 2023. In calculating the sample, a total of 1,280 graduates was considered, taking into account an annual intake of 80 students, divided between Full-time and Evening programs. The sample calculation resulted in a minimum participation of 96 graduates for a 95% confidence level. The methodology involved the application of a semi-structured questionnaire specifically designed for this research, using the Google Forms platform, between March and May, 2024. The questionnaire was composed by multiple-choice 25 questions and open-ended formats, being organized as follows:

- Introduction;

- Informed Consent Form (ICF);

- Participant Information;

- Academic Training Information;

- Professional Practice Information;

- Suggestions and opinions regarding the completed undergraduate program (Appendix A).

The form was distributed to 1,280 Dentistry Course graduates, using the email addresses registered in the Graduation Department of ICT/SJC - UNESP. Eligible participants included: 1) Graduates of ICT/SJC - UNESP between 2002 and 2023 with a registered email address in the Graduation Technical Section; 2) Participants who consented to the Informed Consent Form (ICF) (Appendix B).

The results obtained from the forms were processed using Microsoft Excel spreadsheet editor and organized into graphs and tables, allowing the visualization of the gathered information. Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics and presented in relative and absolute percentages.

Results

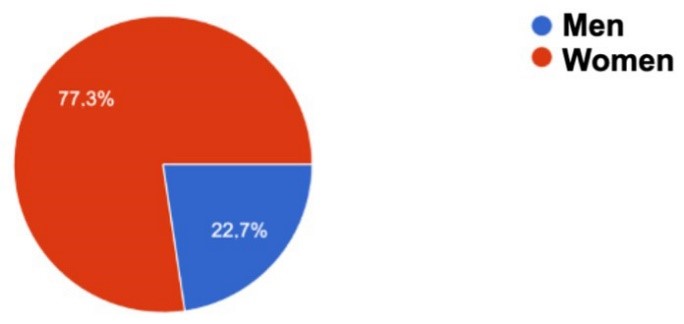

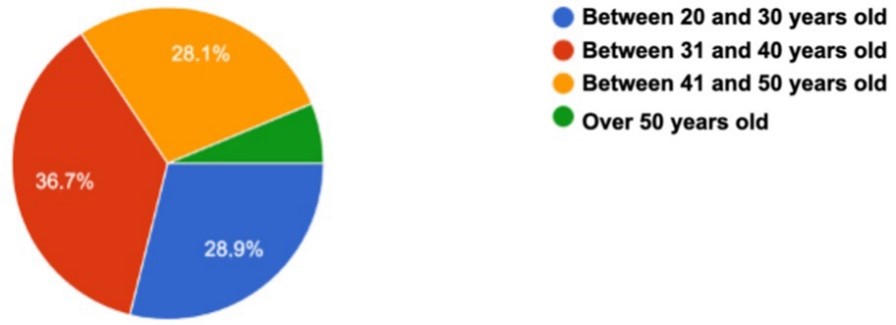

A total of 128 graduates responded the questionnaire, exceeding our sample calculation, and through their responses, various characteristics could be observed in the profile of the graduates from the Faculty of Dentistry. Figure 1 shows the discrepancy between men and women in the profession, with women representing 77.3% of the responses and men only 22.7%. Figure 2 shows the age range diversity of the graduates who participated in the survey, with 36.7% being between 31 and 40 years old, 28.9% between 20 and 30 years old, 28.1% between 41 and 50 years old, and only 6.3% over 50 years old.

Figure 1: Percentage distribution of responses regarding the gender of participating graduates.

Figure 2: Distribution of responses by percentage concerning the age range of participating graduates.

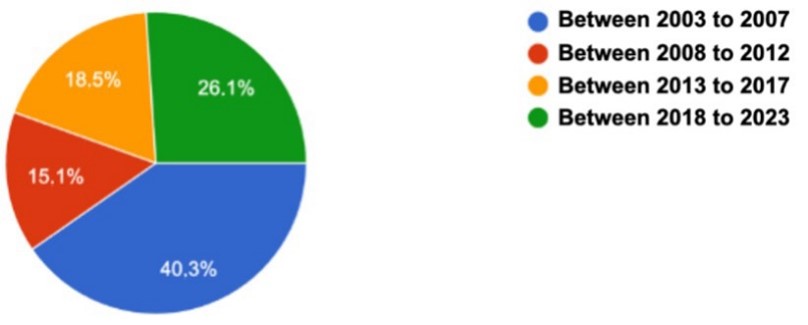

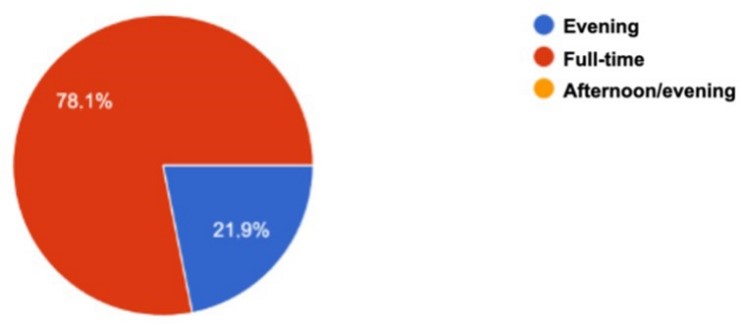

In Figure 3, the results regarding the percentage of participating graduates in each graduation year range can be observed. It shows that 40.3% graduated between 2003 and 2007, 26.1% between 2018 and 2023, 18.5% between 2013 and 2017, and finally 15.1% between 2008 and 2012. Figure 4 shows the study period attended by the graduates, with the majority of participants attending full-time studies (78.1%), while 21.9% attended evening classes, and no participants attended afternoon/evening classes.

Figure 3: Percentage distribution of participating graduates across graduation year intervals.

Figure 4: Percentage distribution of responses regarding the study period attended by participating graduates.

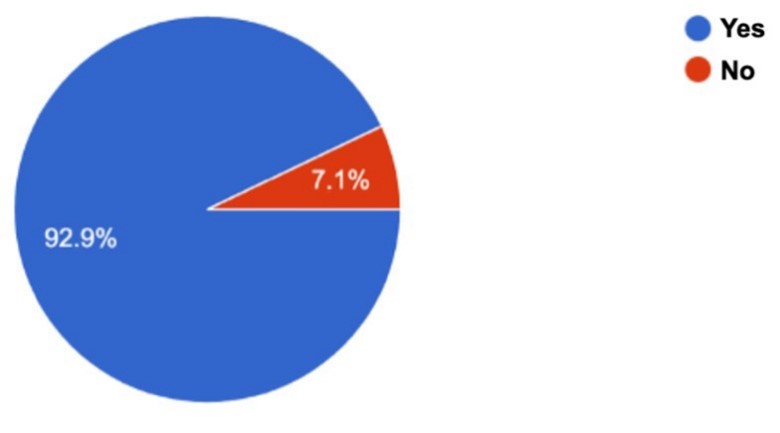

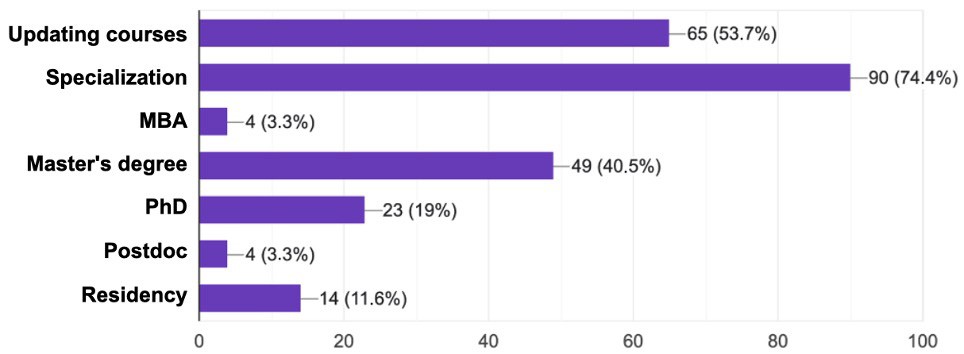

In Figure 5, the responses regarding whether graduates have completed or are currently pursuing any type of postgraduate course, regardless of the course modality, can be observed. 92.9% of participants responded affirmatively, indicating they have completed or are currently pursuing a postgraduate course, while only 7.1% reported not having pursued any type of postgraduate education. Figure 6 provides further insights into the types of postgraduate courses undertaken by the graduates. In this question from the questionnaire, participants could choose one or more options, resulting in a total number of ansers greater than the total number of participants. It is evident that specialization courses are the most prevalent among graduates, selected by 74.4% of them. Following closely are updating courses with 53.7%, and master's and doctoral programs with 40.5% and 19%, respectively, demonstrating the highest participation rates among respondents.

Figure 5: Percentage distribution of responses regarding whether participating graduates are currently enrolled in or have completed a postgraduate course.

Figure 6: Responses regarding types of postgraduate courses completed or in progress by participating graduates.

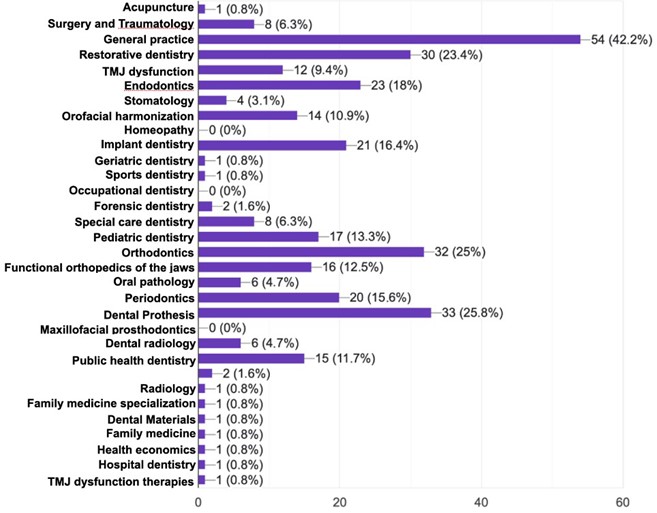

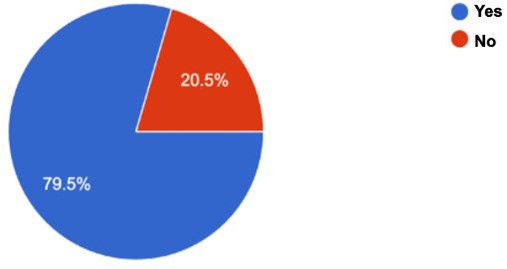

In Figure 7, the responses regarding the specialty or area of practice of these graduates can be observed, with 28 distinct areas selected. It demonstrates that general practice is the most representative area of practice in the results, with 42.2% of participants, followed closely by Dental Prosthesis, Orthodontics, and Operative Dentistry, which occupy the second, third, and fourth positions very closely, with 25.8%, 25%, and 23.4% of responses, respectively. Other areas of practice and specialties can be seen in the table (both the number of participants who chose a particular response and the percentage they represent of the total). Figure 8 provides information on the reading habits of scientific articles among participating graduates; 79.5% reported having the habit of reading articles, while 20.5% do not have this habit.

Figure 9 presents the main sources for research and information seeking among professionals. The majority of graduates reported that scientific articles are their primary source of information, with 81.7%, followed by online courses at 56.3%, conferences at 54.8%, books at 52.4%. Google and social media also show relatively high search rates at 25.4% and 23.8%, respectively.

Figure 7: Responses concerning the specialty or field of practice of the graduates.

Figure 8: Responses regarding the habit of reading scientific articles among the graduates.

Figure 9: Responses regarding the primary sources of information and search habits among the graduates.

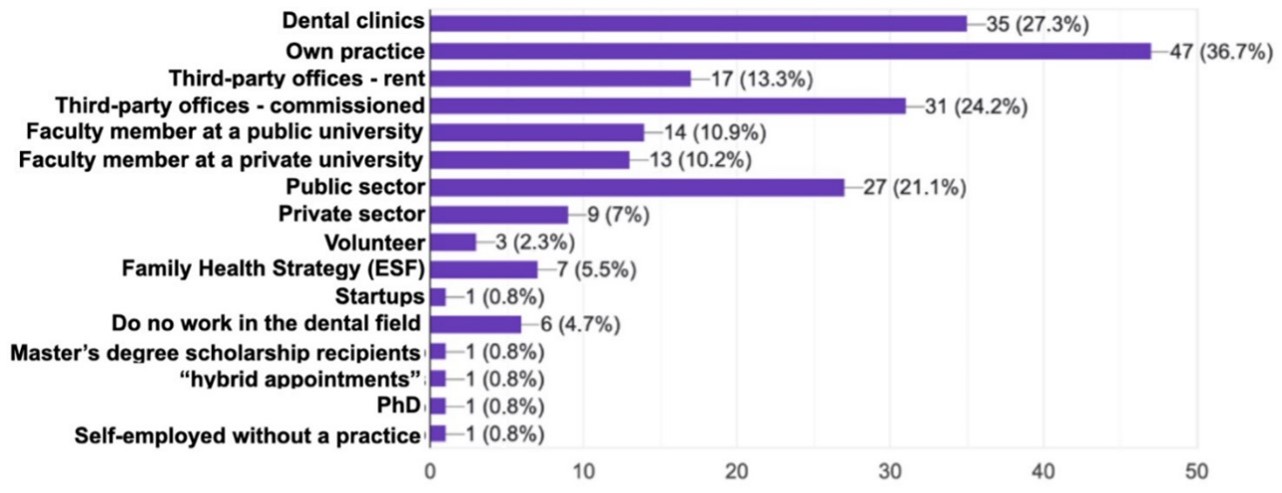

In Figure 10, the results of the responses from graduates regarding the location or locations where they work professionally can be observed. 36.7% reported having their own practice, 27.3% work in dental clinics, 24.2% in third-party offices where they are either commissioned or receive a percentage of the performed treatments. 21.1% work in the public sector, 13.3% work in third-party offices through space rental, 10.9% are faculty members at public institutions, 10.2% are faculty members at private institutions, 7% work in the private sector (companies/industry), 5.5% in the Family Health Strategy (ESF), 4.7% do not work in the dental field of their education, 2.3% are involved in volunteering, and tied with 0.8% of participants are the following categories: startups, master's degree scholarship recipients, "hybrid appointments," doctoral students, self-employed without a practice.

Figure 10: Responses regarding the location or locations of professional activity of the graduates.

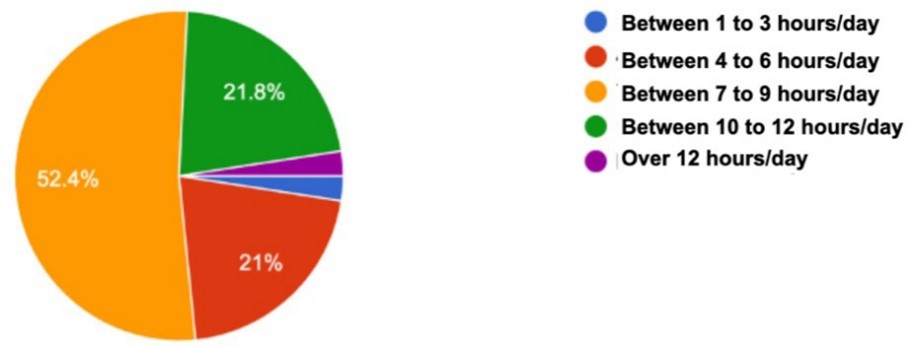

In Figure 11, the results regarding the number of hours worked by the surveyed graduates are shown. The majority of professionals, 52.4%, reported working between 7 to 9 hours per day. Additionally, 21.8% work 10 to 12 hours per day, 21% work 4 to 6 hours per day, and 2.4% of the graduates are tied between those who work more than 12 hours per day and those who work between 1 and 3 hours per day.

In Figure 12, the results concerning the monthly income range of these professionals are presented. The majority, 35.8%, have a monthly income between 5 to 8 minimum wages. Furthermore, 24.4% receive more than 12 minimum wages, 18.7% receive between 9 and 12 minimum wages, 17.9% receive between 1 and 4 minimum wages, and 3.3% receive up to 1 minimum wage.

Figure 11: Percentage of responses regarding the number of hours worked daily by the graduates.

Figure 12: Percentage of responses regarding the monthly income range, based on minimum wages, of the graduates.

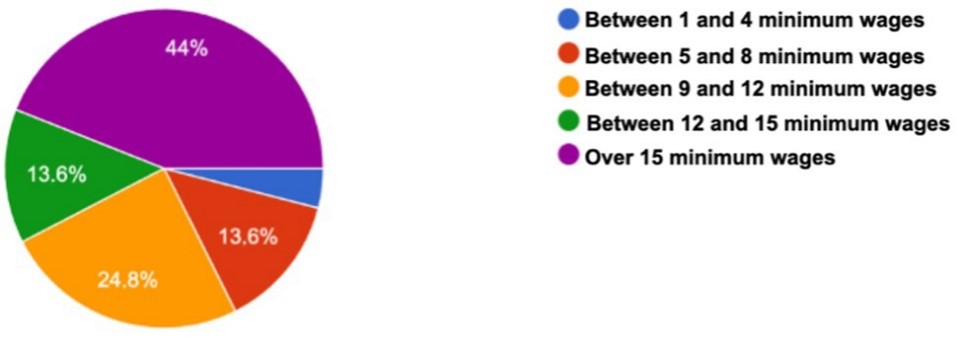

Regarding the Figure 13, it is possible observe the responses about the desired monthly income of the graduates based on their time since graduation. Of the respondents, 44% expected to be earning more than 15 minimum wages, 24.8% expected to be earning between 9 and 12 minimum wages, those who expected to be earning between 5 and 8 minimum wages and 12 to 15 minimum wages each represent 13.6% of the responses, and 4% expected to be earning between 1 and 4 minimum wages.

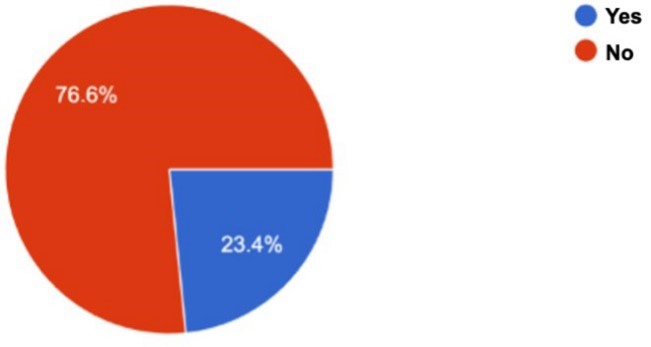

In Figure 14, the results show whether the graduates provide services under dental plans, cooperatives, or health plans. A total of 76.6% of the graduates do not provide these types of services, while 23.4% responded that they do. In Figure 15, still related to this subject, the satisfaction of those providing these services with their financial return is presented. Among them, 83.7% are not satisfied with the financial return, while 16.3% reported being satisfied with the financial return from providing this type of service.

Figure 13: Percentage of responses regarding the desired monthly income, based on minimum wages, of the graduates.

Figure 14: Percentage of responses from graduates who do or do not provide services under agreements, cooperatives, or health plans.

Figure 15: Percentage of responses regarding the satisfaction with the financial return of graduates providing services under agreements, cooperatives, or health plans.

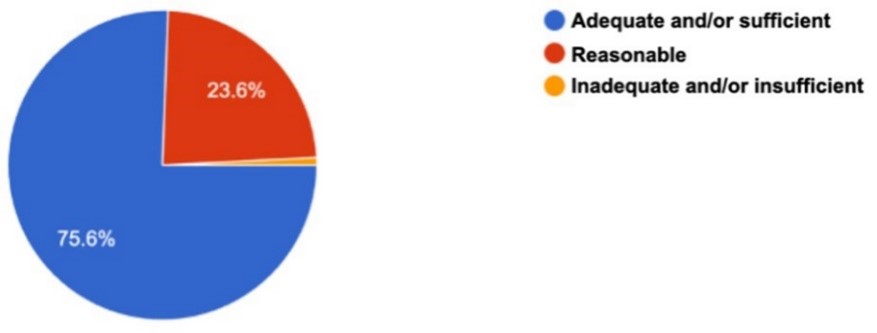

Concerning the graduate’s knowledge, Figure 16 provides an assessment of their perceived level of knowledge acquired during their undergraduate studies. 75.6% rated the acquired knowledge as adequate and/or sufficient, 23.6% as reasonable, and only 0.8% as inadequate and/or insufficient. Regarding the evaluation of adequate preparation for the job market, Figure 17 demonstrates that 52.8% considered themselves well-prepared for the job market, 44.1% considered their preparation partially adequate, and 3.1% considered their preparation inadequate for the job market.

Figure 16: Percentage of responses from graduates regarding the assessment of knowledge acquired during their undergraduate studies.

Figure 17: Percentage of responses from graduates regarding the assessment of professional training adequacy for the job market.

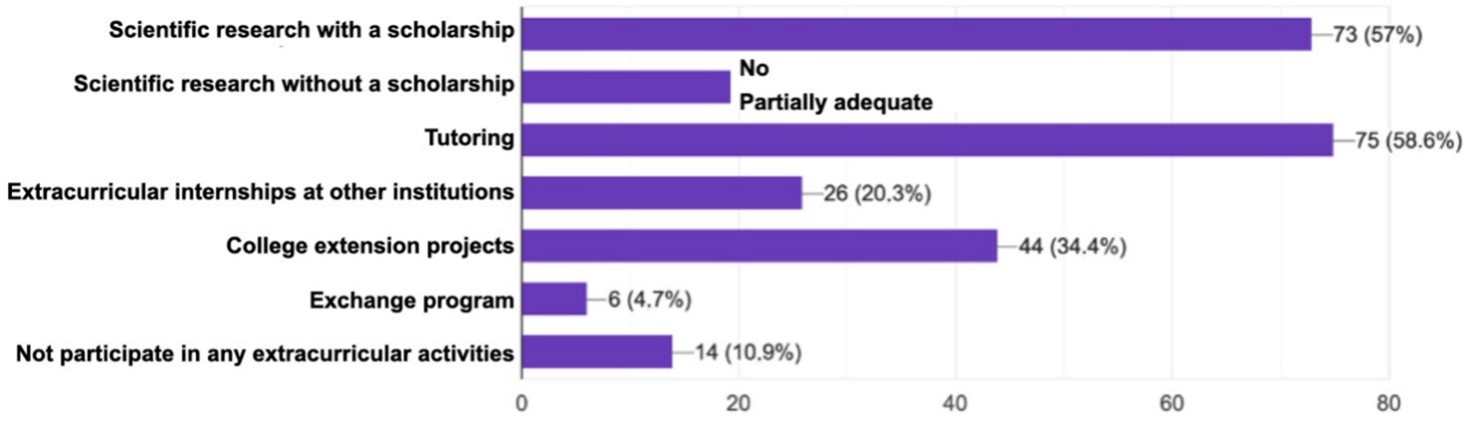

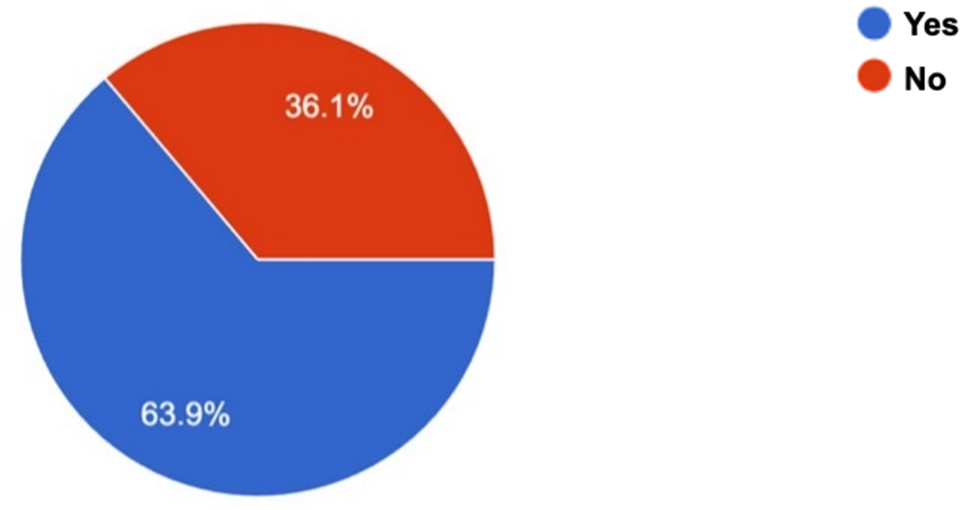

Regarding the graduate’s education, Figure 18 presents results on complementary activities carried out during their undergraduate studies. 58.6% of the graduates engaged in tutoring during their undergraduate studies, 57% participated in scientific research with a scholarship, 34.4% participated in college extension projects, 21.9% engaged in scientific research without a scholarship, 20.3% completed extracurricular internships at other institutions, 10.9% did not participate in any extracurricular activities, and 4.7% participated in an exchange program during their undergraduate studies, either within or outside the country. Regarding the influence of these extracurricular activities on graduates’ entry into the job market, 63.9% responded positively that participating in these activities assisted in their job market entry, while 36.1% classified that these activities did not influence their job market entry. These results are depicted in Figure 19.

Figure 18: Responses regarding complementary activities carried out during the graduation course by the graduates.

Figure 19: Percentage of responses regarding the contribution of complementary activities carried out during the graduation course by the graduates to their insertion into the job market.

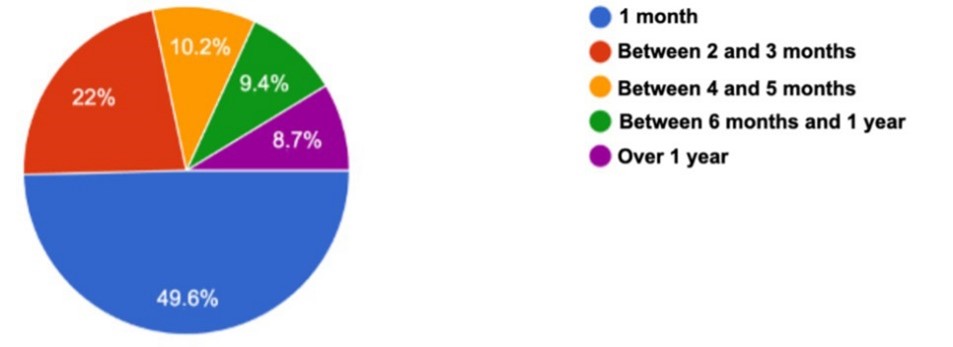

Regarding the evaluation of the greatest difficulties for recent graduates, the majority responded that low remuneration was the main challenge (27.2%), followed by difficulties in managing and administrating their own practice (26.4%). 16.8% reported insecurity in performing procedures, 14.4% quoted a low number of patients, and 12.8% mentioned challenges in entering the job market. Additionally, 0.8% of participants each mentioned difficulties in patient relationships, career planning, and all previously mentioned options, primarily insecurity, as the major challenges they faced as recent graduates. Figure 21 presents the results regarding the experiences of graduates as recent graduates, considering the average time it took participants to enter the job market after graduation: 49.6% reported entering the job market within 1 month after graduation, 22% between 2 and 3 months, 10.2% between 4 and 5 months, 9.4% between 6 months and 1 year, and 8.7% took more than 1 year to enter the job market.

Figure 20: Percentage of responses regarding the greatest difficulty encountered by graduates when they were newly graduated.

Figure 21: Percentage of responses regarding the average time taken by graduates to enter the job market after graduation.

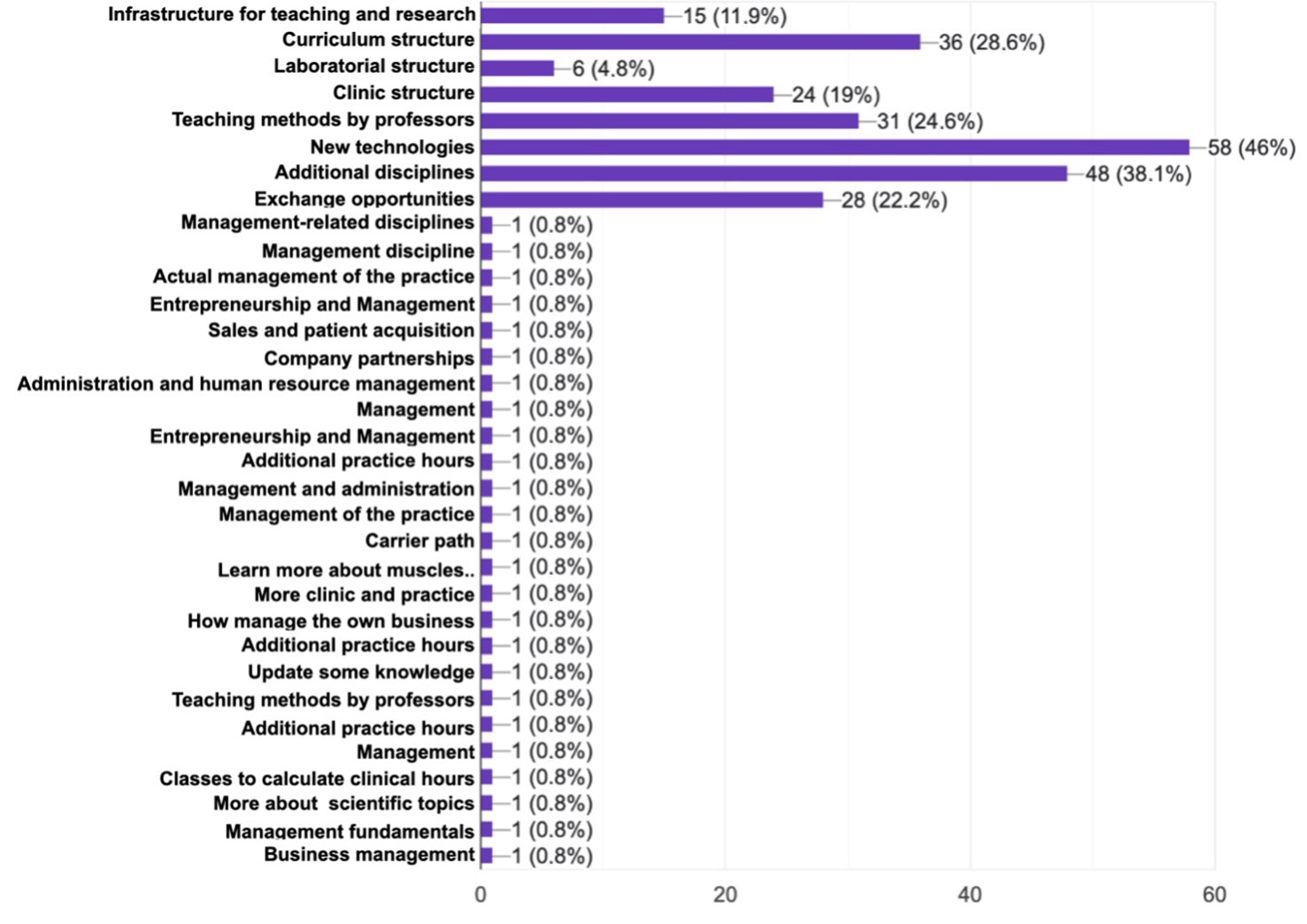

In Figure 22, responses are provided regarding aspects that graduates indicated could be enhanced in the graduation program. 46% of the graduates believe that the integration of new technologies should be more prevalent in the curriculum, while 38.1% emphasized the need for additional disciplines. 28.6% highlighted the importance of improving the curriculum structure, and 24.6% suggested enhancements in teaching methods by professors. Furthermore, 22.2% mentioned the value of exchange opportunities, and 19% proposed improvements in the clinical infrastructure of the program. Additionally, 11.9% highlighted the need for better infrastructure for teaching and research, and 4.7% quoted desiring improvements in laboratory facilities. Additionally, there were 25 other suggestions, each with 0.8% of graduates indicating areas for improvement, including 15 suggestions related to the inclusion of management, administration, and marketing education within the undergraduate curriculum.

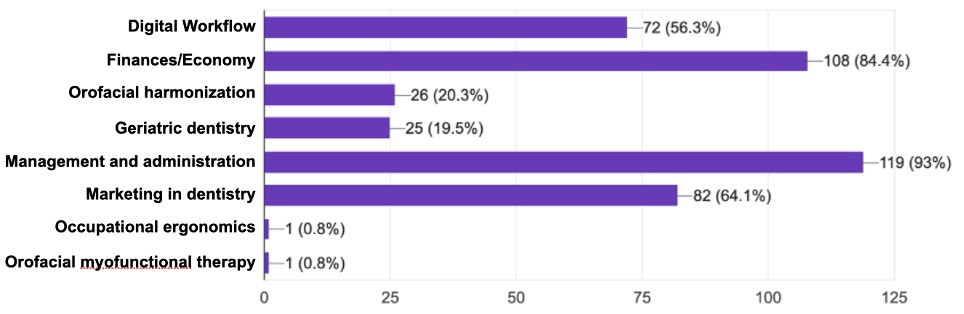

In the same figure, results are presented on suggestions for disciplines that should be incorporated into the undergraduate curriculum according to graduates. 93% advocated for the inclusion of management and administration, while 84.4% recommended the addition of finance and economics. 64.1% suggested integrating marketing specifically tailored to Dentistry, and 56.3% proposed incorporating digital workflow. Further, 20.3% supported the inclusion of Orofacial Harmonization, 19.5% favored incorporating Geriatric Dentistry, and 0.8% each suggested adding Occupational Ergonomics and Orofacial Myofunctional Therapy.

Figure 22: Responses regarding aspects to be improved in the undergraduate course according to the graduates' opinions.

Figure 23: Responses regarding disciplines or content that should be included in the undergraduate course according to the graduates' opinions.

The last question addressed by the survey to the graduates was whether they would enroll in the dentistry course again, and Figure 24 expresses these responses. 73.2% would enroll in dentistry again, while 26.8% would not enroll in dentistry again.

Figure 24: Percentage of responses regarding whether the graduates would enroll in dentistry again.

Discussion

Amorim et al. (2022) and Pinheiro et al. (2016) agree that the feminization of the dental profession is on the rise. The data obtained from the questionnaire responses in this study corroborate this information, as 77.3% of the 128 respondents, or 99 individuals, are female. They observed that this shift is associated to the increasing educational attainment of and the pursuit of gender equality in the labor market. However, the implications of this feminization are perceived differently [2,14, 16]. Amorim et al. (2022) view this as a positive aspect that brings dynamism to the job market, whereas Pinheiro et al. (2016) highlight disparities in working hours and remuneration between genders, indicating that there are still challenges to be addressed in terms of equal opportunities and working conditions [2,14].

According to Garcia and Cobra (2004), the analysis of studies reveals a multifaceted scenario of Dentistry in Brazil, involving professional satisfaction, academic training, job market entry, and working conditions [3]. All authors agree that professional satisfaction among dentists is a crucial aspect to consider. Garcia and Cobra (2004) and Silva et al. (2021) point out that many professionals are dissatisfied with working conditions, mainly due to the low fees paid by dental insurance plans [3,6]. The results obtained corroborate this, as 23.4% of the graduates responded that they work with dental insurance or health plans, and of these, 83.7% expressed dissatisfaction with the financial return from these services. Additionally, another point that corroborates this dissatisfaction is that 26.8% of the graduates in this study stated that they would not choose to study dentistry again if given the opportunity.

Similarly, Mendes et al. (2019) highlight that, although many professionals feel partially satisfied, challenges such as low salaries and inadequate working conditions are prevalent. However, there are divergences in the perception of the severity of these problems [12]. For instance, Ferraz et al. (2021) report greater financial satisfaction among graduates from the State University of Piauí (UESPI), while Costa et al. (2016) indicate a mixed perception of salary satisfaction, varying between good and regular [8,11]. Based on the questionnaire responses, it was observed that only 10 out of 128 graduates expressed satisfaction with their current income, while all others desired a higher income than they currently have, indicating that salary satisfaction can vary between regions and educational institutions.

The need to improve academic training is a consensus among the authors. Ferreira et al. (2013) and Saliba et al. (2012) agree that there is a disconnection between university education and the demands of the job market, suggesting a curriculum review to include administrative and management competencies [10,13]. This fact is evident in the results of this study, as 38.1% of the participants indicated the need for new disciplines in the dental curriculum. When asked which disciplines should be included, 93% selected management and administration. Since respondents could choose more than one option, 84.4% also indicated the need to study finance/economics during their undergraduate studies, highlighting the deficiency in dentists' training regarding the management and administration of their own practices. Silva et al. (2021) and Costa et al. (2016) also emphasize the importance of including disciplines such as Administration, Marketing, and Entrepreneurship to better prepare graduates [6,11].

Disagreement arises regarding the level of preparation perceived by graduates. While Silva et al. (2021) indicate that most graduates consider themselves only partially prepared for the job market, Pinheiro et al. (2016) highlight that many professionals manage to enter the job market quickly, finding employment within a month after graduation [6,14]. This difference may be related to the graduates' expectations and the specific opportunities available in different regions. The data obtained from the questionnaire responses corroborate Pinheiro et al. (2016), as 49.6% of the graduates entered the job market within one month after graduation [14]. Regarding their perceived preparedness for the job market, 52.8% considered that the content learned was sufficient to enter the market after graduation, indicating a discrepancy with Silva et al. (2021) [6]. However, the data are very close, as 44.1% considered themselves partially prepared and 3.1% considered the education insufficient for job market entry, totaling 47.2% of the participants.

Regarding the need to improve academic training, another finding from this study is that 92.9% of the graduates have either taken or are currently taking some form of postgraduate course, demonstrating that dentists are constantly updating their knowledge and striving to be better prepared for the job market with additional training beyond their undergraduate education. In addition, approximately 40.4% of the country’s postgraduate graduates published at least six papers during their academic journey [16].

The authors agree that entering the job market is a significant challenge for recent graduates. Bastos et al. (2003) and Silva et al. (2022) noted that many graduates opt for private practice, seeking financial security and social status despite the initial career difficulties [7,9]. This corroborates with the data obtained in the results of this study, as 60.9% of respondents work either in their own practice or rent a third-party practice space. Opinions vary regarding the effectiveness of internships and preparation for the job market. While Bastos et al. (2003) believe that internships in primary care and public service are valuable, Silva et al. (2022) indicate that graduates feel well-prepared for simple procedures but less so for complex ones [7,9]. According to the questionnaire results, only 4 individuals expressed the need for more internship hours and clinical practice, with the majority focusing on other areas needing improvement and considering the current internship hours adequate. However, 19% of graduates reported a need for improvements in clinical facilities for conducting internships. This may be because most respondents (78.1%) completed the full-time course, which limits internship opportunities due to the course's high daytime hours.

There is a consensus on the importance of public policies that promote the continuous integration of Dentists into public initiatives. Amorim et al. (2022) and Mendes et al. (2019) highlighted the need to increase the coverage of the population receiving oral health care through the Unified Health System (SUS), suggesting that greater involvement in the public sector could help alleviate the challenges faced by professionals in the job market [2, 12]. However, there are differences in perception regarding the opportunities offered by the public sector. While Amorim et al. (2022) view engagement in public initiatives as a viable solution to many of the professionals' issues, Pinheiro et al. (2016) observed that, despite a shift towards the public sector, the private sector still predominates [2,14]. This suggests that the attractiveness of the public sector may not be sufficient to retain all necessary professionals. The results obtained from the questionnaire responses support Pinheiro et al. (2016) findings regarding the cumulative categories involving the public sector [14]. Those working in public service, serving as faculty in public institutions, or participating in the Family Health Strategy (ESF) represent only 37.5% of the graduates. Silva et al. (2020) explains a lot about the uncertainty and the necessity to reinvent ourselves during the restricted period of the pandemic of COVID 19, in this point of view the public service demonstrates its safety to dentists and an option for those who do not wish to undertake and assume the risks of the market [15]. Moimaz et al. (2022) highlight in their study that postgraduate graduates take on significant roles within public service, particularly in collective health initiatives and in strengthening Brazil's Unified Health System (SUS) [16].

The opinions among the authors reveal both points of agreement and significant divergences regarding the current scenario of Dentistry in Brazil. There is a general consensus on the need to improve academic training and working conditions, as well as policies that encourage engagement in the public sector. However, perceptions vary regarding the level of preparedness of graduates, professional satisfaction, and the implications of the feminization of the profession. These perceptions are crucial for developing strategies that promote sustainability and appreciation of the dental profession in the country.

Conclusion

Dentistry in Brazil faces significant challenges related to education, job market entry, and professional satisfaction. The need for the curriculum renovation and more effective public policies is evident to promote a more valued and sustainable practice. The feminization of the profession and rapid job market entry highlight both the dynamics and opportunities present, but also point to persistent disparities and areas needing improvement. An integrated analysis of these aspects is essential to strengthen the field of dentistry in the country.

Funding: This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Brazil. Gives new Statutes to the Faculties of Medicine. Collection of Laws of the Empire of Brazil. 1884; 2(1): 478.

- Amorim GO, Paz AM, Carvalho HAA. Entering the labor market and the Recife School of Dentistry graduate’s profile. Rev. ABENO, 2022; 22(2): 1256. DOI: 10.30979/revabeno.v22i2.1541.

- Garcia PPNS, Cobra CS. Working conditions and satisfaction of dentists accredited to dental assistance plans. Rev Odontol UNESP, 2004; 33(3): 115-122.

- Smiling Brazil Program completes 10 years.

- Freitas SFT de, Calvo MCM, Lacerda JT de. Collective health and new curricular directives in dentistry: a proposal for undergraduate courses. Trab educ saúde, 2012; 10(2): 223–234. doi: 10.1590/S1981-77462012000200003.

- Silva AB, Oliveira CD, Santos EF. Alumni profiling of dentists graduated from the Federal University of Ceará and their perceptions on thelabor market. ABENO, 2021; 21(1): 1073. DOI: 10.30979/rev.abeno.v21i1.1073.

- Bastos JR de M, Aquilante AG, Almeida BS de, Lauris JRP, Bijella VT. Professional profile analysis of dentists graduated at Bauru dental School - University of São Paulo between 1996 and 2000. J Appl Oral Sci, 2003; 11(4): 283–289. Doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572003000400003.

- Ferraz M, Ângela AL, Nolêto MSC, Martins LLN, Bandeira SRL, Portela SGC, et al. Dentistry Graduates Profiles at the State University of Piaui. Rev ABENO, 2018; 18(1): 56-62. DOI: 10.30979/rev.abeno.v18i1.392.

- Silva AB, Oliveira CD, Santos EF. Perception of entry into in the labor market among dental graduates from a university in southern Brazil. ABENO, 2022; 22(2): 1645. DOI: 10.30979/revabeno.v22i1.1645.

- Saliba NA, Moimaz SAS, Prado RL, Garbin CAS. Perception of dentists about professional training and difficulties of insertion in the labor market. Rev Odontol UNESP. Rev. odontol. UNESP, 2012; 41(5).

- Costa BA de O, Gonçalves CF, Zanin L, Flório FM. Introduction of newly graduated dental students from the State of Tocantins into the job market. ABENO, 2016; 16(2).

- Mendes HJ, Matos PES, Lima BV, do Nascimento HR, Prado FO. Dentistry graduates and its insertion in the labor market. Rev. Saúde.Com, 2019; 15(4): 1629-1634.

- Ferreira NP, Ferreira AP, Freire MCM. Job market in dentistry: historical context and perspectives. Rev. odontol. UNESP, 2013; 42(4): 304-309.

- Pinheiro IAG, Noro LRA. Dentistry graduates: the dream of the liberal profession confronted with the reality of oral health. Rev ABENO, 2016; 16(1): 13-24.

- Silva JMF, Zanet CG, Trezza R, Lamour L, Beraldo AL. The importance of dental office management in times of COVID 19 and how to resume activities in post-pandemic. Braz Dent Sci, 2020; 23(2): SUPP. 2 - Dentistry and Sars-CoV-2. https://doi.org/10.14295/bds.2020.v23i2.2297.

- Moimaz SAS, Saliba O, Garbin CAS, Saliba TA, Chiba FY, Saliba NA. Análise da atuação profissional de egressos da Pós-Graduação em Odontologia na área de Saúde Coletiva. Rev Bras Pós-graduação, 2022; 18(39): 1–14.