Assessment of Nutritional Status and Associated Factors among Tharu Students of Primary School in Kanchanpur District, Nepal

Ganesh Bhandari1,*, Ranjan kapali1, Prakash Raj Bhatt1, Ashnita raut2, Shilpa Lamichhane3, Kripa Thapa Magar4, Jivan Raj Bohara1

MPH, School of Health and Allied Sciences, Pokhara University

MPH, University of North Texas Health science Centre, USA

Program Manager, Visible Impact, Kathmandu4Central Department of Public health, Institute of Medicine, Kathmandu

MPH, central Department of Public Health, Institute of Medicne, Kathmandu

Received Date: 20/04/2022; Published Date: 02/05/2022

*Corresponding author: Ganesh Bhandari, MPH, School of Health and Allied Sciences, Pokhara University, Nepal

Abstract

Introduction: Nutrition is a key indicator of one's overall health. School age is the most active period of a child's development. Malnutrition during childhood is one of the major causes of child mortality in developing nations. Chronic malnutrition in children has been related to delayed cognitive development and major health problems later in life, lowering quality of life. The Tharu community is believed to be socially and economically disadvantaged. Hence, the purpose of this study is to evaluate the nutritional status and characteristics related with it among primary school aged children from the Tharu population in Kanchanpur district.

Methods: Cross-sectional analytical study was conducted among 365 students of Tharu Community studying in primary level in government school of Kanchanpur district. Structured questionnaire and anthropometric measurement were used for measuring height and weight of the children to generate required information. Convenience sampling was done for selection of the schools and random sampling for data collection among students. Data entry was performed in EPI-data and SPSS (version 16.0) was used for analysis of associated factors. Chi-square test was applied for associations between the variables as per the research objectives. Similarly, Emergency Nutrition Assessment (ENA) was used to for calculating Z-scores of Nutritional Indicators.

Results: Moderate and severe stunting were found in 25.6 percent and 20.6 percent of the population, respectively. While severe underweight was found in 7.0 percent of the population, whereas moderate underweight was found in 36.8 percent. In terms of BMI for age, 30.1 percent of children were underweight. There was an association between mother's educational status and stunting, as well as family type and children's BMI.

Conclusion: Malnutrition is a serious concern in the Tharu community. The prevalence of stunting and underweight was 40.2 percent and 45.8. Dietary standards among Tharu community primary school students were determined to be inadequate. Because no previous research has been done in Nepal on this issue in the Tharu community, this study will serve as a starting point for future research in similar conditions. This will also assist concerned authorities in reducing undernutrition.

Keywords: Stunting; Wasting; Tharu Community

Introduction

Nutritional status is a prime indicator of health. School age is the most active period of a child's development. The primary school years are a period of rapid physical and mental development for children. According to studies, poor nutrition is one of the most common factors of low school enrolment, excessive absenteeism, early dropout, and bad classroom performance among primary school-aged children [1-3]. The nutritional status of children does not only directly reflect the socioeconomic status of the family and social wellbeing of the community, but also the efficiency of the health care system, and the influence of the surrounding environment [4].

Under nutrition in childhood was and is one of the major reasons behind the high child mortality rates observed in developing countries. Chronic under nutrition in childhood is linked to delayed cognitive development and chronic health impairments later in life that reduce the quality of life of individuals [5,6]. Nutritional status is an important index of this quality. In this respect, understanding the nutritional status of children has far-reaching implications for the better development of future generations.

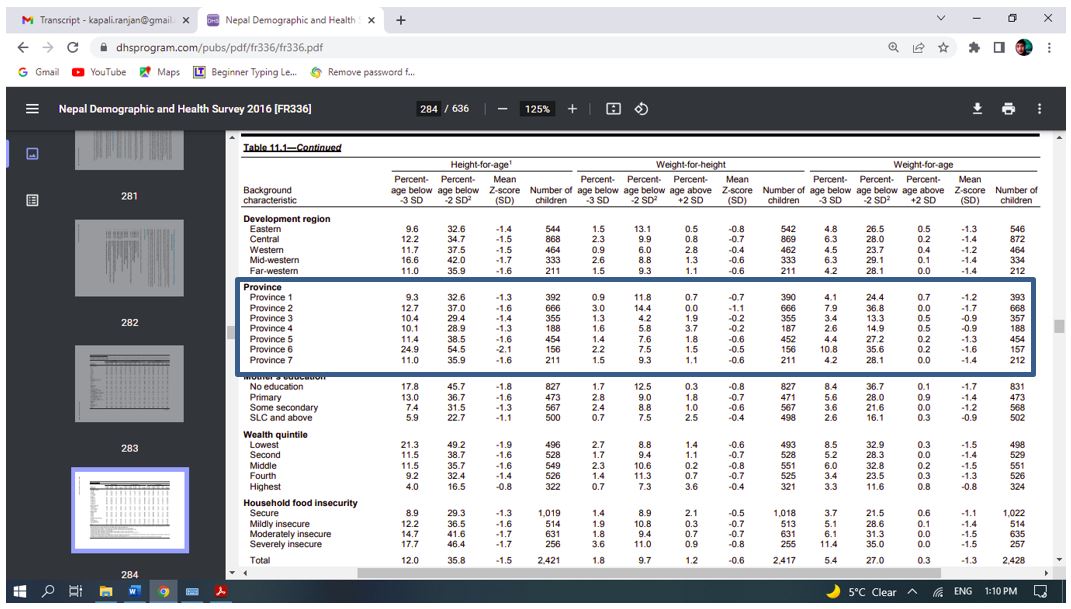

In last 15 years, Nepal has shown notable decrease in under 5 mortality rate, infant mortality rate and maternal mortality ratio [7]. These steep declines in mortality rates have been attributed to strong public health interventions including the control of the micro‐nutrient deficiencies and Maternal, Infants and Young Child Nutrition (MIYCN) during the same period. However, the neonatal mortality rate has remained stagnant over the same time period and accounts for more than two‐third of infant deaths [8]. The prevailing high rate of child under‐nutrition in the country is one of the major contributing factors of under‐five mortality. The NDHS 2016 has shown 36 percent of children less than 5 years of age suffering from chronic under‐nutrition (stunting) while more than 10 percent are acute under‐nourished [9]. Furthermore, national nutrition status estimates mask wide inequities. Children from the lowest quintile or whose mother has no education are more than twice likely to be stunted than those from richest quintile or whose mother has secondary level or more education. The mountain zone has the highest stunting rate of 56 percent, while the Terai has the lowest rate (37.4%) [10].

The Tharu ethnic group in Nepal is likewise a backward ethnic group that lives in the western Terai region [11]. There hasn’t been any previous research in Nepal on the nutritional condition of such ethnic groups. As a result, the purpose of this study is to shed light on the nutritional status and associated factors of Tharu community primary school children’s in Kanchanpur district. Finally, assisting local health authorities in putting study findings to good use and developing beneficial intervention methods in collaboration with other relevant organizations.

Material and Methods

A cross-sectional analytical survey was undertaken in Kanchanpur district from …. To .... The students in the selected schools during the study period was the study population. The required sample size for the study was calculated using population proportion formula and a total number of students in the study was 365 from four government schools in the district. For school selection, convenience sampling was used, and for student’s selection, a random sampling technique was used. Two visits were made to locate absentee kids in the school. To gather the necessary data, respondents were asked to complete a Nepali version (local language) structured questionnaire and an interview. Name, age, sex, standard in which he/she was studying, physical examination, and personal cleanliness were all included in the questionnaire. The questionnaire was taken from the similar study. Weighing machine and measuring tape were the tools employed for anthropometric measurement. Each child was recognized by name, age, and gender, and their weight was measured in kilograms using a weighing scale. The data collectors were .

The scale was frequently calibrated against a known weight. Cloths were not removed because there was insufficient privacy (in classroom). A measuring tape was used to mark height in centimeters on the wall at school. The students were instructed to take off their shoes and stand with their heels together and their heads positioned perpendicular to their bodies. The calibration was done by lowering a scale to the uppermost point on the heads of students standing against the wall. To the nearest 0.5cm, the height was measured.

The questionnaire was pre-tested, and the weighing machine's functionality was checked on a regular basis. Epi-data, ENA, and SPSS version 16 were utilized to enter data, calculate z-scores and factor linked with nutritional status, and analyze data respectively.

The ethical approval was obtained from ethical review board of Nepal Health Research Council (NHRC). A letter of permission was obtained from the education section of municipality as well as the school administrators. Written consent was taken from parents and assent consent from students. Privacy and confidentiality were maintained throughout the study.

Findings

Socio-demographic characteristics

Table 1: Socio-Demographic characteristics.

More than half of the children (55.1%) were between the ages of 60 and 120 months, while 44.1 percent were between the ages of 120 and 180 months. Only 0.8 percent of the children were older than 180 months. The data on the family structure of the primary school children in the study region revealed that 214 (58.8%) of the 365 respondents belonged to a nuclear family, 123 (33.2%) to a joint family, and 27 (7.4%) to an extended family. In the Tharu community in Kanchanpur district, it has been determined that joint and extended families are less practical than nuclear families. The findings also revealed that there were more girls in the schools than boys. 162 (44.4%) of the 365 respondents were males, while 203 (55.6%) were girls.

According to the findings, 64 (17.5%) mothers were illiterate and 301 (82.5%) mothers were literate out of 365 respondents. Respondents' fathers were illiterate in 4.7 percent of cases, but literate in 95.3 percent of cases. Parents of children are employed in agricultural activity, with 199 (54.5%) farmers, 25.5 percent labor (carpenter, driver, etc.), 28 (7.7%) in government service, and 45 in foreign employment (12.3%).

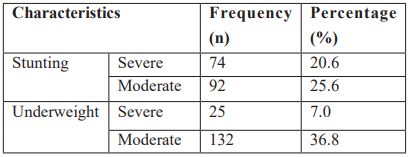

Prevalence of Stunting and Underweight

Table 2: Prevalence of stunting and Underweight.

Stunting was found to be prevalent in 46.2 percent of the population. Children who were severely stunted accounted for 20.6 percent of the total, while 25.6 percent were moderately stunted. In total, 43.7 percent of young children were underweight. 7 percent of them were severely underweight, and 36.8% were moderately underweight.

BMI for Age

Table 3: BMI for age.

The table 3 shows that 30.1 percent of children were underweight for BMI. More than half (62.4 %) of the children enrolled in the study were normal. Overweight children were 6.1 percent whereas 1.4 percent of them were obese according to their Body Mass Index (BMI).

Association between socio-demographic variables and nutritional status

Table 4: Association between socio-demographic variables and nutritional status.

Severe Underweight (SU) and Moderate Underweight (MU) children accounted for 3.6 and 20.9 percent of children aged 60 to 120 months, respectively, whereas 2.5 and 15.9 percent of children aged 120 to 180 months. The number of Severely Stunted (SS) and moderately stunted (MS) children in the 60–120-month age group was 6.0 and 14.6 percent, respectively, but the number of Severely Stunted (SS) and moderately stunted (MS) children in the 120–180-month age group was 15.6 and 13.6 percent. The ages of the children with stunting and underweight were found to have a significant association.

Girls were found to be underweight more likely than the boys. There was no evidence for an association between a child's sex and weight. Stunting was also shown to be more common in girls than in boys. There was no evidence for an association between children's sexes and stunting.

In children of illiterate mothers, the prevalence of severe and moderate underweight was 1.4 and 6.1 percent, respectively, but it was 5.6 and 30.6 percent, respectively, in children of literate mothers. The prevalence of severe and moderate stunting among children of illiterate mothers was determined to be 4.0 and 7.6 percent, respectively. Severe and moderate stunting were seen in 20.9 and 43.4 percent of children with literate mothers, respectively. There was no association identified between a mother's educational status and her child's weight. However, there was an association between mothers' educational status and their children's stunting.

Children of illiterate fathers had a prevalence of severe and moderate underweight of 0.6 and 1.9 percent, respectively, but children of literate fathers had a prevalence of 6.4 and 34.8 percent, respectively. There was no significant association identified between a mother's educational status and her child's weight. The frequency of severe and moderate stunting among the children of illiterate fathers was found to be 0.3 and 2.3 percent, respectively. Severe and moderate stunting were seen in 21.5 and 26.2 percent of children with literate fathers, respectively.

The prevalence of severe and moderate underweight in children from nuclear families was 4.2 and 22.6 percent, respectively, whereas it was 2.5 and 19.3 percent in children from joint families, and the prevalence of severe and moderate underweight in children from extended families was 0.3 and 2.2 percent, respectively.

Children from nuclear families had a prevalence of severe and moderate stunting of 13.3% and 17.6%, respectively, whereas children from joint families had a prevalence of 7.0 and 9.0 percent, and children from extended families had a prevalence of 1.7 and 2.0 percent, respectively. There was no evidence of a link between family types with stunting and underweight.

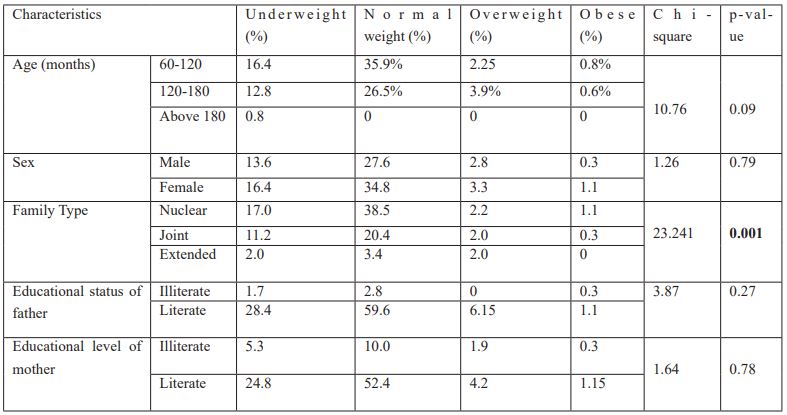

Association between socio-demographic variables and BMI of children

Table 5: Association between socio-demographic variables and BMI of children.

16.4 percent of children aged 60 to 120 months were underweight, 35.9% were normal weight, 2.25 percent were overweight, and 0.8 percent were obese, according to the findings. 12.8 percent of children aged 120-180 months are underweight, 26.5 percent are normal weight, 3.9 percent are overweight, and 0.6 percent are obese. In the age category of 180 months and older, 0.8 percent of children are underweight. In addition, 13.6 percent of males and 16.4 percent of females were found to be in the underweight category of BMI for their age. Normal weight children made up 27.6% of males and 34.8 percent of females. There was no evidence of a link between children's sex and their BMI for their age. According to the above table, 17.0 percent of nuclear family children are underweight, 38.5 percent are normal weight, 2.2 percent are overweight, and 1.1 percent are obese. 11.2 percent of children in a joint household are underweight, 20.4 percent are normal weight, 2.0 percent are overweight, and 0.3 percent are obese. 0.8 percent of extended family members' children are underweight. According to the findings of the study, the type of family and the BMI of the children have a substantial association. When BMI was adjusted for age, the frequency of underweight was found to be 1.7 percent among illiterate father's children and 28.4 percent among literate father's children. There was no association between father and mother's educational levels and age-related BMI.

Discussion

This study was carried out to find the nutritional status and associated factors in children of primary level school in Tharu community of Kanchanpur district of Nepal. Here, prevalence of malnutrition was to be found in two major indicators of malnutrition on basis of Z score of Height for age and Weight for age indicate as stunting and underweight respectively. The major findings of the study are discussed here briefly.

In this study prevalence of stunting and underweight among primary school level going children of Tharu Community in Kanchanpur district is 46.2 and 43.7 percent respectively. According to Nepal Demographic Health Survey 2016, 36 percent of children are stunted (short for their age) and 27 percent are underweight (low weight for their age). The prevalence of stunting was higher compared to underweight. Data in this study is relatively high comparing to the national survey reports. A descriptive cross-sectional study in Dhankuta town (Dhankuta district) and Inaruwa town (Sunsari district) to find out Nutritional status and morbidity pattern among governmental primary school children in the Eastern Nepal found 61% of the students were found to be malnourished. The students were more stunted (21.5%) than wasted (10.4%). Comparing to this study there is very low prevalence of stunting in this study [12]. Another study in Pokhara discovered that 26% of students were undernourished, 13% were stunted, 12% were wasted, and only 1% were both stunted and wasted [1]. In this study prevalence of stunting is very low compared to the present study. In a cross-sectional research conducted in remote hill settlements in the Illam area, 17 percent of children under the age of five were moderately underweight and 10.4% were severely underweight. Similarly, 22.9 percent and 17.5 percent of the population were determined to be moderately and severely stunted [13]. Only about ten percent of the people were judged to be moderately or severely wasted.

The prevalence of underweight was seen higher in boys i.e., 47.4 percent in boys and 40.9 percent in girls. Boys are seen more severely underweight by 9.0 percent while girls were 5.4 percent. A study conducted in India found that undernutrition was prevalent in 44.56 percent of males and 37.32 percent of females, respectively, and stunting was prevalent in 26.31 percent of males and 21.37 percent of females [14]. This study's data are also sparse in comparison to ours.

The BMI for age among the children in this study was 30.1 percent underweight, 62.4 percent normal weight, 6.1 percent overweight and 1.4 percent obese. Thinness was found to be 22.4 percent in Humla district and 29.4 percent in Mugu district, according to a research done to examine nutritional status among children visiting health camps in two hilly areas in Nepal. Thinness was found to be 30.1 percent in this investigation. So it exhibits comparable data in comparison to Mugu district where as it is higher than the Humla district [15]. A study was carried out in the Kavre district. According to the findings, the prevalence of underweight, stunting, and thinness was found to be 30.85 percent, 24.54 percent, and 10.05 percent among rural school children in Kavre district, respectively [2]. In comparison to the current study, this investigation revealed lower statistics on the prevalence of underweight, stunting and thinness.

This study discovered an association between a mother's educational level and stunting. (p=0.025). However, there is no link between a father's educational degree and his children's nutritional state. This research also demonstrates a link between BMI and family types. (p=0.001). There was no link identified between a child's sex and BMI, mother and father's education and BMI. This could be due to the fact that this study only has a small number of participants, and the sample chosen may not be representative.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that malnutrition is a serious problem in the Tharu community. Mother’s education and type of the families played an important role in lowering the risk of chronic malnutrition (stunting) and underweight status among the children of study group. The nutritional standards of Tharu community primary school students were determined to be inadequate. In compared to national survey reports, the prevalence of stunting and underweight was found to be greater. School children's health and nutritional standards were determined to be poor in this investigation. This study bears the restriction of being representative of only Tharu people from Kanchanpur district, and so cannot be extrapolated to the full population of the country.

In Nepal, no studies have been undertaken to investigate the nutritional status and associated determinants among elementary school students in the Tharu group. This study will serve as a starting point for future studies in comparable circumstances. This will also aid concerned authorities in taking steps to reduce undernutrition.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to offer their heartfelt gratitude to all respondents who generously shared their time and expertise in our study effort. Similarly, we express our heartfelt gratitude to the Department of Public Health, Sanepa Lalitpur National Open College.

References

- Levine N, Lazarus GS. Subcutaneous fat necrosis after paracentesis: Report of a case in a patient with acute pancreatitis. Arch Dermatol, 1976; 112(7): 993-994. doi:10.1001/archderm.112.7.993.

- Wick MR. Panniculitis: A summary. Semin Diagn Pathol, 2017; 34(3): 261-272. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2016.12.004.

- Christian HA. Relapsing febrile nodular nonsuppurative panniculitis. Archives of Internal Medicine, 1928; 42(3): 338-351.

- Ivkov simi M, Jovanovi M, Polja M, Verica Uran KI, Milan M A T I. Livedoid vasculitis idiopathica. skin, locomotor and soft tissue pathology, 2001; 9(1); 141-142.

- Wu F, Zou CC. Childhood Weber-Christian disease: clinical investigation and virus detection. Acta Paediatr, 2007; 96(11): 1665-1669. doi:10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00498.x

- Avivi I, Rosenbaum H, Levy Y, Rowe J. Myelodysplastic syndrome and associated skin lesions: a review of the literature. Leuk Res, 1999; 23(4): 323-330. doi:10.1016/s0145-2126(98)00161-1

- Agarwal A, Barrow W, Selim MA, Nicholas MW. Refractory Subcutaneous Sweet Syndrome Treated with Adalimumab. JAMA Dermatol, 2016; 152(7): 842-844. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2016.0503.

- White JW Jr, Winkelmann RK. Weber-Christian panniculitis: a review of 30 cases with this diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol, 1998; 39(1): 56-62. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70402-5.

- White JW Jr, Winkelmann RK. Weber-Christian panniculitis: a review of 30 cases with this diagnosis. J Am Acad Dermatol, 1998; 39(1): 56-62. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70402-5.

- Moraes AJ, Soares PM, Zapata AL, Lotito AP, Sallum AM, Silva CA. Panniculitis in childhood and adolescence. Pediatr Int, 2006; 48(1): 48-53. doi:10.1111/j.1442-200X.2006.02169.x

- Saghir S, Meskini T, Ettair S, Erreimi N, Mouane N. La maladie de Weber-Christian: s'agit-il d'un état pré-leucémique? [Weber-Christian's disease: a preleukemic disorder?]. Pan Afr Med J, 2019; 32: 127. Published 2019 Mar 18. doi:10.11604/pamj.2019.32.127.16106