The Efficacy of Probiotic Supplementations on Glycemic Control, Lipid Profile, Inflammation Biomarkers and Body Weight Changes Among Type 2 Diabetes Patients

Louay Labban*

Department of Nutrition and health sciences, Al Jazeera Private University, Syria

Received Date: 30/03/2022; Published Date: 20/04/2022

*Corresponding author: Louay Labban*, Department of Nutrition and health sciences, Al Jazeera Private University,Syria

Abstract

Background: The World Health Organization in 2002 defined probiotics as living organisms, in which foods and dietary supplements can be found that, when ingested, can improve the health of the host. Disturbances of intestinal biology contribute to the pathogenesis of DM. Studies have shown that the gut microbiome plays a role in the development and progression of type 1 and type 2 diabetes and its complications. This study was designed to evaluate the effects of multi-species of probiotic supplementation on fasting blood glucose, lipid profile, inflammatory biomarkers, and body weight changes in type 2 diabetic patients.

Participants and methods: 65 type 2 diabetics were divided into 2 groups T (trial) and C (control) or placebo. The T group received daily one capsule of 1 species of probiotic and C group received capsules filled with roasted ground chickpea. Fasting blood glucose, Serum Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNFα) and C Reactive Protein (CRP), HDLC, LDLC, TG, TC levels and BMI were measured at beginning and the end of the study which lasted for 10 weeks.

Results and discussion: Fasting plasma glucose significantly reduced in the probiotic group compared to the control group respectively, 131.1 ± 10.1 vs 1 6.5 ± 10.3 (p < 0.05). Furthermore, a significant reduction was also evident TC in the trial group (18 ± 31 vs 199 ± 21) in the control group and the difference was significant p < 0.05). The group which received probiotic also showed significant reduction in TG (p < 0.05) compare to control group (128 ± 23 vs 1 1 ± 32 respectively). Also, the LDL value, significantly reduced in the probiotic compared to the control group 123 ± 27 and 1 9 ± 31 (p < 0.05). Probiotic supplementation significantly increased HDL 1.3 ± 13 vs 29.8 ± 12.6 (p < 0.05), We found significant differences in the serum levels of inflammatory markers at the end of the study. Probiotic supplementation decreases CRP (mg/dL) levels and TNFa (pg/ml) (± 1.68 3.33 vs 3.6 ± 2.31and 5. ±5.1vs 5.6 ± 7.8 respectively) and the difference was statistically significant (p<0.05). Probiotics reduced BMI of participants in trial group (27.6 ± 5.2 vs 33.8 ± 10.1) and the difference was significant (p <0.05(.

Conclusion: The results of this study suggest that probiotic supplementation may be an effective and beneficial way to improve glucose levels, lipids, inflammatory biomarkers, and body weight in patients with non-insulin dependent diabetes or type 2 diabeties.

Keywords: Probiotics, bifidobacteria, lipid profile, glycemic control, CRP, TNFα, BMI

Introduction

World Health Organization in 2002 defined probiotics as “living organisms in food and functional foods”, when ingested may promote host health beyond their inherent basal nutrient content [1]. The Gut Microbiome (GM) plays a role in the development and progression of type 1 and type 2 diabetes and its complications. Disturbances in gut biology contribute to the pathogenesis of DM. GM has been shown to affect drug effectiveness. such as prebiotics, probiotics and synbiotics, may improve glycemic control as well as DM-related metabolic profiles. There is preliminary evidence that it may even help treat the cardiovascular, ophthalmic, neurological, and renal complications of DM and even aid in the prevention of DM. Larger studies is needed before gut probiotics are widely used in clinical practice as an adjunct to current diabetes management [2]. The role of the gut microbiota in the management of diabetes has been demonstrated. Several ongoing trials are investigating the effects of probiotics and prebiotics, widely used to modulate the gut microbiome, on inflammatory factors and biomarkers induced by oxidative stress in patients with diabetes; however, their findings are controversial. Naturally present in fruits, raw vegetables, dairy products (especially fermented products), they are an integral part of the gut microbiota as a component of the common flora. The main probiotic microorganisms used in human nutrition are lactic acid bacteria such as Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium [3,4].

Compared with healthy subjects, patients with chronic inflammatory diseases, particularly Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) and Ankylosing Spondylitis (SpA), have an altered gut microbiota called is a biological disorder. Biological dysregulation with increased permeability allows cellular or bacterial antigens to interact more readily with the host immune system [5]. This intestinal inflammation is associated with systemic inflammation and may be responsible for the development of several autoimmune diseases and contribute to their exacerbations [6-9].

Evidence from studies in rats and humans has shown that probiotics locally and systemic modulation of the immune system, leading to a reduction in mucosal inflammation and proinflammatory cytokines [10]. They also reduced arthritis in mice [11]. They can reach the immune system of the intestinal lining, persist for a time, and initiate a specific immune response. The interaction between probiotic strains and enterocytes is critical for the controlled production of cytokines and chemokines secreted by epithelial cells. Indeed, it has been shown that some probiotic organisms can modulate the in vitro expression of pro and anti-inflammatory molecules in a strain-dependent manner. Indeed, treatment with certain strains of Lactobacillus reduces intestinal permeability and reduces the severity of arthritis [12, 13]. The effects of probiotics have been well-studied on allergic diseases and Crohn's disease, for which they have not shown any real benefit.

Alterations in the intestinal microbiota can modulate mechanisms involving risk factors for cardiovascular diseases, including dyslipidemias [14]. The ingestion of probiotics is associated with various beneficial effects on human health and modifies the physiological homeostasis of the intestinal flora. Probiotics are microorganisms with some particular characteristics: human origin, safety in human use, bile and acid resistance, survival in the intestine, at least temporary colonization of the human gut, adhesion to the mucosa and bacteriocine production [15].

Beneficial bacteria of probiotics are usually used to protect the host from microorganism [16]. These bacteria are beneficial in the prevention of different types of diarrhea such as antibiotic and traveler's and they play a role in the management of gastritis resulted from Helicobacter pylori. Additionally, the efficacy of probiotics has been shown in the treatment of infectious diarrhea, in IBD, in pouchitis and in food allergy. They can reduce the severity of the symptoms of IBD and of lactose intolerance. As a final point, it has been acknowledged that probiotics play an important role in the prevention of tumor growth and carcinogenesis process [17].

The nutritional benefits of probiotics consist of protective and beneficial effects against certain health problems have been demonstrated in many randomized controlled trials which support the evidence of its advantages, are growing [18]. The evidence for the positive effects of prebiotics to alleviate constipation and treat hepatic encephalopathy has also been shown in numerous studies. In other studies probiotics showed a lower level of proof of efficacy, including prevention of colon cancer, intestinal infection, and the relapse of IBD [19]. There is a high level of evidence for positive effects of some probiotics in the relief of lactose intolerance, antibiotic-associated intestinal disorders and gastroenteritis [20]. Recent studies have suggested preventive properties against intestinal colonization of bad gut microorganism such as Clostridium difficile and Helicobacter pylori [21, 22, 23, and 24].

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the effects of probiotic supplementation on levels of serum C-Reactive Protein (CRP), inflammatory biomarkers TNF-α, fasting plasma glucose (FPG), lipid profile and weight changes in diabetic patients.

Patients and Methods

A total of 65 participants (35 females and 30 males) were recruited for this study. Participants were diagnosed with type 2 diabetes and were recruited consecutively among patients who visited a tertiary private endocrine clinic. The patients included were aged from 33 years 56, diagnosed with type 2 diabetes. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethical committee of A'Sharqiyah University of (ethic code: ASU 21073). Informed consent was from obtained from each participant.

The study was a, double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled trial which lasted for 12 weeks. The recruitment of the participants was done by the researchers. Both participants and researchers were blinded and supplement contents were kept confidential until all subjects had completed the study. Only one of the staff on the development committee of was aware of whether supplement was probiotics filled or placebo.

During this study, all subjects of group (T), received a capsule of probiotic once a day and Group C the control (or placebo) received also a capsule once a day. Both capsules had a completely similar appearance. The capsule which was given to T group had the product (Pronutrition Advanced Probiotics 2 X 109 CFU/capsule) that contained 14 bacterial strains: Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus. delbrueckii ssp, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, Lactobacillus casei, Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus rhamnosus, Lactobacillus salivarius, Lactococcus lactis ssp, Bacillus subtilis, Streptococcus thermophiles, Bifidobacterium bifidum, Bifidobacterium breve, Bifidobacterium infantis, and Bifidobacterium longum. The placebo capsule contained ground roasted chickpea capsule. All other types of probiotic products were forbidden during the study for both the trial and control group.

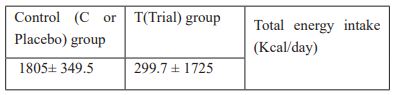

Anthropometric measurements were also taken for participants of each group, including weight, height, waist and hip circumferences at beginning and the end of the study. Body weight was measured on a Seca 755 dial column medical scale (accuracy of 0.5 kg), and height was measured using a stadiometer (accuracy of 0.1 cm). BMI was calculated by dividing weight (kg) by the square of the height (m2). Waist circumference was measured at the level of the iliac crest and hip circumference was measured at the site of the largest circumference between the waist and the thighs using a tape measure. In this study, the waist to hip ratio was calculated (the waist circumference divided by the hip circumference). A 2-day food recall was collected from each participant before the start of this study to calculate the total energy intake. The patients in both groups were given isocaloric diet which consisted of 55% carbohydrates, 20 % Protein and 25 % fat. The total calorie content of diets consumed by both groups is presented in Table 1:

Table 1: Calorie content of participants in trial and control diets

Figure 1: Gender distribution of participants in both groups.

Results and Discussion

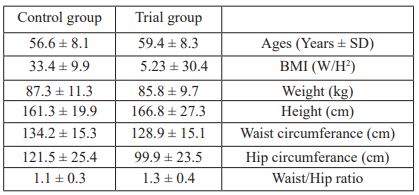

The study sample consisted of 64 type 2 diabetes patients. The Trial group consisted of 36 patients (16 females and 20 males) and the placebo group consisted of 28 patients (13 females and 15 males). There were no significant differences between patients of this study for anthropometric measures (Table 2).

Furthermore, the data from this study was reported after considering gender, age, BMI, and dietary energy intake

Table 2: Age and anthropometric measurements of participants in both groups

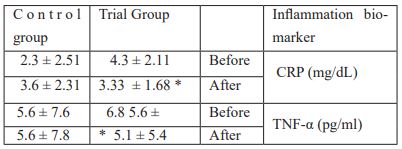

The study has shown that supplementation of multispecies probiotics has significantly (p<0.05) decreased the CRP and TNF-α in the trial group. CRP level was 4.3 ± 2.11 at the beginning and decreased to 1.68 ± 3.33 in trial group whereas in the control group CRP level was 5.6 ± 7.6 and 5.6 ± 7.8 at the beginning and at the end of the study for the control group respectively. These data are presented in Table 3.

Table 3: Alterations in inflammatory biomarkers at the beginning and at the end of the study for both groups.

* Significant difference p<0.05

There are many studies which support our findings. Most of these studies reported the effect of probiotics or synbiotics on circulating (serum and plasma) inflammatory marker (hs-CRP). Probiotic supplementation reduced hs-CRP the inflammation biomarker (24). In another study which demonstrated that compared with the control condition, probiotic intake produced a beneficial effect in reducing the levels of plasma inflammation markers, including tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) p < 0.05) and C-reactive protein (CRP) [25, 26].

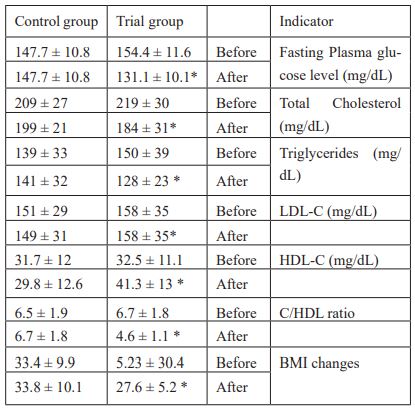

Table 4 shows that probiotics supplementation of multispecies probiotics to type 2 diabetics significantly reduced their fasting plasma glucose. The effect of probiotics was significant of probiotics on FPG. In the trial group, FPG at the beginning of this study was 154.4 ± 11.6 and it was dropped to 131.1 ± 10.1(mg/dL) and the difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05) whereas the drop in the control group was not significant (147.7 ± 10.8 vs 147.7 ± 10.8). The data presented in Table 4. It has also showed that supplementation of probiotics to type 2 diabetics reduced their Total Cholesterol level. TC level (mg/dL) was 219 ± 30 at the beginning of the study and decreased to 184 ± 31 and the difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05). There was also a significant decrease in Triglyceride level between Trial and Control group after supplementation. The TG level was 150 ± 39 mg/dL before supplementation and became 128±23 mg/dL and the TG in Control group was 139 ± 33 mg/dL and became 141 ± 32 mg/dL before and after supplementation respectively. The LDL-C had the same pattern as it decreased significantly after supplementation with probiotics. In Trial group LDL-C level was 158 ± 35 mg/dL before supplementation and went down to 158 ± 35 after supplementation and the LDL-C level in Control group was 151 ± 29 mg/dL before supplementation and became 149 ± 31 mg/dL. The difference was significant between the two groups after supplementation (p < 0.05).

The effect of supplementation was clear on HDL-C level. Supplementation significantly improved HDL-C level in Trial group but not in Control group. HDL-C level went up in Trial group from 32.5 ± 11.1 to 41.3 ± 13 mg/dL and surprisingly HDL-C decreased in Control group as HDL-C level was 31.7 ± 12 mg/dL before supplementation and became 29.8 ± 12.6 mg/dL after supplementation. The difference was significant (p < 0.05) between groups after supplementation. Supplementation also improved C-HDL-C ratio. In trial group, the ratio decreased from 6.7 ± 1.8 before supplementation to 4.6 ± 1.1 after supplementation and the difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05). On the contrary, the ratio was not improved in the Control group. However, the difference was significant between both groups after supplementation with probiotics.

Table 4: Fasting plasma glucose, lipid profile and body weight changes for trial and control groups at the beginning and at the end of this study.

*Significant difference p<0.05

Supplementation with probiotics had its effect on BMI. BMI significantly improved after supplementation in Trial group as it was 5.23 ± 30.4 before supplementaion and became 27.6 ± 5.2 whereas the improvement in BMI in Control group was not noticed. The difference was statisticall signifcantly between both groups (p<0.05).

The results that we obtained from this study were in agreement with many other studies about the effect of probiotic supplementation on glucose level. In a study by Ostadrahimi et al 2015 found that the beneficial effects of Kefir (a traditional collection of beneficial microbes) were reported on glycated hemoglobin A (HbA1c) level, and weight loss of an indexed diabetic mellitus patient. The patient as a supplement of her routine anti-diabetic drugs consumed Probiotic kefir. After 90 days of consumption the patient, have about 4 kg weight losses, and her HbA1c decreased from 7.9 to 7.1. Depth of sleep and energizing effects of kefir was also from very remarkable findings of this case, as reported by the patient [26]. Many studies have shown results similar to the results we obtained from this study showing that supplementation with probiotics significantly reduced total cholesterol, LDL-c, and triglycerides and increased HDL-c [27- 30]

We tried in this study to find out if there was any adverse effect of using probiotics on gastrointestinal health including bloating, constipation, GERD or allergies on participants from both groups although the patients in the Control group did not ingest any number of probiotics and we wanted to know the placebo effect on those patients. In Trial group 13 individual or (36-1%) did not have any symptoms comparing with 14 individuals (50%) in the Control group. As for bloating, 3 individuals in Trial group reported bloating whereas 4 (14.3%) reported the same symptoms in the Control group. The number of individuals who had constipation and GERD was similar 5(13.8%) in Trial group but it was 5 (13.8 %) for constipation and 1(2.8%) for GERD in Control group. More people reported allergies in Trial group comparing with Control group. 6 (16.7%) vs 2 (5.6%). For abdominal pain and diarrhea similar number reported in Trial group 1 (3.6 %) and in the Control group 1 (2.8%) for abdominal pain and diarrhea. The number of cases of GI complications is summarized in Table 5:

Table 5: The number and percentage of GI complication after ingesting probiotics supplementation.

Conclusion

Supplementation with probiotics significantly reduced total cholesterol, LDL-C, and triglycerides and increased HDL-C. Some benefits were observed on glycemic control, inflammation, and anthropometric measurements. The present study suggests that probiotic supplementation should be indicated as adjunctive treatment for glycemic control and dyslipidemias. More studies should be performed to clarify long-term effects, as well as the influence of probiotics in combination with medications.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank the staff at the central laboratory for their kind participation in analyzing the blood samples of the patients participated in this study. The author would also like to extend his gratitude for the Dean of Health Science College for his advice and encouragemnt.

The author claims that there was no conflict of interest.

References

- Yao K, Zeng L, He Q, Wang W, Lei J, Zou X. Effect of Probiotics on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis of 12 Randomized Controlled Trials. Med Sci Monit, 2017; 23: 3044-3053. doi: 10.12659/msm.902600. PMID: 28638006; PMCID: PMC5491138.

- Alagiakrishnan K, Halverson T. Holistic perspective of the role of gut microbes in diabetes mellitus and its management. World J Diabetes. 2021; 12(9): 1463-1478. doi: 10.4239/wjd.v12.i9.1463. PMID: 34630900; PMCID: PMC8472496

- Wang P. Probiotic bacteria: A viable adjuvant therapy for relieving symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. Inflammopharmacology, 2016; 24: 189–196.

- Diamanti AP, Manuela Rosado M, Laganà B, D’Amelio R. Microbiota and Chronic Inflammatory Arthritis: An Interwoven Link. J. Transl. Med, 2016; 14: 233.

- Mielants H, De Vos M, Cuvelier C, Veys EM. The Role of Gut Inflammation in the Pathogenesis of Spondyloarthropathies. Acta Clin. Belg, 1996; 51: 340–349.

- Tlaskalová-Hogenová H, Štepánková R, Hudcovic T, Tucková L, Cukrowska B, Lodinová-Žádnıková R, et al. Commensal Bacteria (Normal Microflora), Mucosal Immunity and Chronic Inflammatory and Autoimmune Diseases. Immunol. Lett, 2004; 93: 97–108.

- Sartor RB. Review Article: Role of the Enteric Microflora in the Pathogenesis of Intestinal Inflammation and Arthritis. Aliment Pharmacol. Ther. 1997; 11 (Suppl. 3): 17–22; discussion 22–23.

- McCulloch J, Lydyard PM, Rook GAW. Rheumatoid arthritis: How well do the theories fit the evidence? Clin. Exp. Immunol. 1993; 92: 1–6.

- Danning CL, Boumpas DT. Commonly Used Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs in the Treatment of Inflammatory Arthritis: An Update on Mechanisms of Action. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 1998; 16: 595–604.

- Delcenserie V, Martel D, Lamoureux M, Amiot J, Boutin Y, Roy D. Immunomodulatory Effects of Probiotics in the Intestinal Tract. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol, 2008; 10: 37–54.

- Kano H, Kaneko T, Kaminogawa S. Oral Intake of Lactobacillus Delbrueckii Subsp. Bulgaricus OLL1073R-1 Prevents Collagen-Induced Arthritis in Mice. J. Food Prot. 2002; 65: 153–160.

- So JS, Kwon HK, Lee CG, Yi HJ, Park JA, Lim SY, et al. Lactobacillus Casei Suppresses Experimental Arthritis by Down-Regulating T Helper 1 Effector Functions. Mol. Immunol, 2008; 45: 2690–2699.

- Strowski MZ, Wiedenmann B. Probiotic Carbohydrates Reduce Intestinal Permeability and Inflammation in Metabolic Diseases, Gut, 2009; 58: 1044–1045.

- Gadelha CJMU, Bezerra AN. Effects of probiotics on the lipid profile: systematic review. J Vasc Bras. 2019; 18: e20180124. doi: 10.1590/1677-5449.180124. PMID: 31447899; PMCID: PMC6690648.

- Montalto M, Arancio F, Izzi D, Cuoco L, Curigliano V, Manna R, et al. I probiotici: storia, definizione, requisiti e possibili applicazioni terapeutiche [Probiotics: history, definition, requirements and possible therapeutic applications]. Ann Ital Med Int, 2002; 17(3): 157-165. Italian. PMID: 12402663.

- Kühbacher T, Ott SJ, Helwig U, Mimura T, Rizzello F, Kleessen B, et al. Gut. 2006; 55(6): 833-841.

- Wilhelm SM, Brubaker CM, Varcak EA, Kale-Pradhan PB. Effectiveness of probiotics in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Pharmacotherapy. 2008; 28(4): 496-505. doi: 10.1592/phco.28.4.496. PMID: 18363533.

- Marteau P, Boutron-Ruault MC. Nutritional advantages of probiotics and prebiotics. Br J Nutr, 2002; 87 Suppl 2: S153-157. doi: 10.1079/BJNBJN2002531. PMID: 12088512.

- De Vrese M, Schrezenmeir J. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol. 2008; 111: 1-66. doi: 10.1007/10_2008_097.

- Saavedra JM, Tschernia A. Br J Nutr. 2002; 87 Suppl 2: S241-246. doi: 10.1079/BJNBJN/2002543.

- Cary VA, Boullata J. J Clin Nurs. 2010; 19(7-8): 904-916. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03123.x.

- Yao K, Zeng L, He Q, Wang W, Lei J, Zou X. Effect of Probiotics on Glucose and Lipid Metabolism in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Meta-Analysis of 12 Randomized Controlled Trials. Med Sci Monit, 2017; 23: 3044-3053. doi: 10.12659/msm.902600. PMID: 28638006; PMCID: PMC5491138.

- Ostadrahimi A, Taghizadeh A, Mobasseri M, et al. Effect of probiotic fermented milk (kefir) on glycemic control and lipid profile in type 2 diabetic patients: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled clinical trial. Iran J Public Health, 2015; 44(2): 228-237.

- Zheng HJ, Guo J, Jia Q, Huang YS, Huang WJ, Zhang W, et al. The effect of probiotic and synbiotic supplementation on biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress in diabetic patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pharmacol Res, 2019; 142: 303-313. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2019.02.016. Epub 2019 Feb 19. PMID: 30794924.

- Ding LN, Ding WY, Ning J, Wang Y, Yan Y, Wang ZB. Effects of Probiotic Supplementation on Inflammatory Markers and Glucose Homeostasis in Adults with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Pharmacol, 2021; 12: 770861. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.770861. PMID: 34955840; PMCID: PMC8706119.

- Plaza-Díaz J, Ruiz-Ojeda FJ, Vilchez-Padial LM, Gil A. Evidence of the Anti-Inflammatory Effects of Probiotics and Synbiotics in Intestinal Chronic Diseases. Nutrients, 2017; 9(6): 555.

- Gadelha CJMU, Bezerra AN. Effects of probiotics on the lipid profile: systematic review. J Vasc Bras, 2019; 18: e20180124. doi:10.1590/1677-5449.180124

- Zhang J, Ma S, Wu S, Guo C, Long S, Tan H. J Diabetes Res. 2019; 2019: 5364730.

- Fortes PM, Marques SM, Viana KA, Costa LR, Naghettini AV, Costa PS. Syst Rev. 2018; 7(1): 165.

- Louay Labban. “The Scope of Therapeutic Use of Probiotics in Management of Diabetes Mellitus”. EC Nutrition 1.5, 2015: 254-258.