Eating Habits and Lifestyle Behaviors During Covid-19 Lockdown in Lebanon

Christina Al Rahbany, Samer Sakr and Ali Al Khatib*

Department of Nutrition and Food Sciences, School of Arts and Sciences, Lebanese International University, Lebanon

Department of Biological and Chemical Sciences, School of Arts and Sciences, Lebanese International University, Lebanon

Received Date: 27/06/2021; Published Date: 08/07/2021

*Corresponding author: Ali Al Khatib, Department of Nutrition and Food Sciences, School of Arts and Sciences, Lebanese International University, Beirut, Lebanon, P.O. Box 146404. Email: ali.alkhatib@liu.edu.lb

Abstract

Background: Around the world, eating habits and lifestyle behaviors have been influenced by the confinement and isolation measures imposed to contain the transmission of the SARS Cov-2 virus causing the COVID-19 pandemic.

Objective: The aim of this study was to assess the impact of those restrictive measures on the dietary habits and lifestyles of residents in Lebanon.

Methods: An online questionnaire was conducted during January 2021. It included 21 questions divided into three main parts. The first part was related to the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants, the second part included diet-related questions such as those concerning changes in diet quality, meal quantity, weight gain, and overeating and the third and final part of the questionnaire was related to lifestyle changes such as physical activity, smoking, caffeine consumption, and screen time during and before quarantine. The results were analysed via statistical analysis computed using the IBM-SPSS 21® software. Spearman correlation, Chi-Square Test of Independence and McNeman analysis were used in analysis. Results were considered significant for p value< 0.05.

Results: 1749 Lebanese residents participated in this study and results showed that the lockdown had a positive association with some eating habits where respondents who consumed only home-made foods increased from 33% before the lockdown to 42% during the lockdown (p. <0.001). Respondents who never consume fast foods (such as pizzas and burgers) accounted for 8.6% before the lockdown vs. 20.2% during the lockdown (p. <0.001). There was also a decrease in frequent meat consumption habits (35% before the lockdown vs 29.7% during the lockdown) (p. <0.001). No impact was observed on unhealthy snack consumption (chocolate, crackers, chips, etc…). On the contrary, the lockdown had a negative effect on the dietary behaviors of the respondents: 48.4% reported consuming more meals, and 43.3% reported gaining weight during quarantine. Results of this study also showed an increase in smoking among low-income populations, an increase incaffeine consumption among young adults, and a significant increase in screen time (p. <0.001). Meanwhilephysical activity hours significantly declined (p. <0.001).

Conclusion: Lockdowns cannot be deemed exclusively “positive” or “negative” when it comes to dietary behavior. The results of this study could be used to anticipate trends and form future policies in response to the noted changes in dietary behaviors and lifestyle factors among the Lebanese population. It is recommended that health policymakers consider these results when setting future policies pertaining to extended quarantine measures. The public should also be aware of the negative effects lockdowns appear to have on the individual and community’s health, as shown in this study.

Keywords: COVID-19; Eating habits; Lifestyle behavior; Diet quality; Food consumption

Introduction

The Coronavirus Disease of 2019 (COVID-19), caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), was initially reported in Wuhan (China), as per the World Health Organization (WHO), from where it spread to more than two hundred countries and territories. As of January 19 2021, there have been 96,122,866 confirmed cases of COVID-19, including 2,052,317 deaths with a 3% mortality rate as reported by the WHO [1].

In order to prevent getting infected with COVID-19, the USA Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended restrictions such as social isolation and total lockdowns [2] that were observed to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic and appeared beneficial in reducing the spread of the virus [3].

Social isolation measures had several effects on different levels, including health target criteria of this current study. While abiding by governmental restrictions during this pandemic, people who confined to their homes changed their eating behaviours, moving to an unhealthier lifestyle, which included frequent snacking, and eventually less physical activity. Hence, such sedentary lifestyles within societies impose health consequences in the long run, regarding obesity, cardiovascular risk problems, etc [4].

Eating habits, physical activity, and other weight-related lifestyle behaviours may have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic even among children in cooperation with the WHO and governments' recommendations to prevent the transmission of the disease, schools and colleges were forced to close, pushing children to resort to distance learning through online classes. Therefore, COVID‐19, via these school closures, “may exacerbate the epidemic of childhood obesity and increase gaps in obesity risk. In addition to increasing out‐of‐school time, the COVID‐19 pandemic exacerbates all the risk factors for weight gain associated with summer recess” [5]. The closing of schools and the imposition of stay-at-home orders build challenges concerning food environments and physical activity for children [6]. Sedentary lifestyles and screen times are expected to increase under social distancing orders; available data showed that “online video game usage is already soaring”. Screen time is known to be associated with higher rates of obesity in children, most probably because of the dual issues of sedentary time and the association between screen time and snacking [7].

As for adults, many studies conducted worldwide observed negative impacts resulting from confinement measures during the COVID-19 pandemic on weight gain, physical activity, and eating behaviours. One international survey showed that home confinement resulted in a “negative effect on physical activity in all its forms, whether vigorous, moderate, walking or overall. On the other hand, daily sitting time increased from 5 to 8 hours daily”. Additionally, food consumption and meal patterns were unhealthier during confinement, with only alcohol binge drinking decreasing significantly [8]. Other similar studies also showed negative associations between the lockdown and unhealthy eating behaviours as well as negative lifestyle changes, namely in the UAE [9], UK [10,11], Poland [12,13], Lithuania [14], USA [15], and Italy [16].

Lebanon, also known as "the Lebanese Republic," is a country in the Levant region of Western Asia. According to the Lebanese Ministry of Public Health (MOPH), as of January 18 2021, there have been 255,956 confirmed and reported cases of COVID-19 in Lebanon, with 1,959 reported deaths from the virus (death rate is 0.8%) in 2020 [17]. In March 2020, the government declared "public mobilization," issued orders for people to stay-at-home, and closed the borders, with full lockdown of nonessential services and thus developed a policy to control the transmission of the virus through the MOPH, abiding by the recommendations of the World Health Organization. The MOPH thus forced three very restrictive national lockdowns in March 2020 (for two months), November 2020 (for 2 weeks), and in January 2021 (for around 1 month).

Little research has been done in Lebanon regarding the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on different socio-economic aspects. However, what we know is that the pandemic severely impacted Lebanon because it occurred amid political and economic chaos. The unrest began in October 2019, when a banking crisis and a civil uprising led to a change in political aspects and pushed the country into an economic catastrophe leading to a massive devaluation in the national currency. The Lebanese Lira. The lockdowns and government restrictions to contain the virus led to a further worsening of the economic crisis.

Furthermore, Lebanese populations have been at risk for poor mental health for several decades due to the distressing events of military conflicts, political insecurity and instability. Moreover, Lebanon recently witnessed the worst economic crisis in its history with extraordinary unemployment rates, inflation, poverty, and devaluation of the national currency [18].

There is no data available yet regarding the impact of home-confinement and lockdown on the eating behaviors and lifestyles of Lebanese residents. Thus, this research aims to address whether or not the pandemic has affected the eating habits, physical activity, alcohol consumption, smoking habits, and screen time (for work and study) compared to before the home-confinement.

The primary objective of this study is to assess how COVID-19 home-confinement measures affected the dietary and lifestyle habits of Lebanese residents. The secondary objective is to develop recommendations for the community and health policymakers as a result of data showed in this study.

Materials and Methods

Survey Methodology

An online questionnaire was conducted and filled between the 11th and the 19th of January 2021 by a range of Lebanese residents. The survey was administered using an online platform, namely Google forms, that is accessible through any device connected to the Internet. It was circulated using different social media platforms such as Facebook ®, Instagram ®, WhatsApp ®, and Twitter ®. This method facilitates reaching a diverse sample and is easy to fill and analyze. The questions in the survey were inspired from similar questionnaires administered in other countries, namely the UAE [9], USA [19], Italy [16], Qatar [20], and one International Survey [8]. The questionnaire was validated via face validation where it was prepared by the main researcher and then reviewed by two other researchers. Then, it was piloted to a small group of people constituting of 20 individuals who answered the questions and voiced out possible areas for improvement. The survey was amended accordingly. The study included adult residents of Lebanon (above 18 years old), with access to the internet in order to complete the online questionnaire. The needed representative sample size needed was calculated with a sample size calculator based on World Bank estimated population size of Lebanon in year 2019.

The questionnaire included three main parts. The first included nine socio-demographic questions: age, gender, marital status, education level, field of study, family income status, number of persons in the household, place of residency during the pandemic, and finally, whether or not the respondent was abiding by the lockdown measures. The second part of the questionnaire included thirteen diet-related questions: whether or not the respondent had gained weight during the pandemic, and if yes how much; the dietary behaviours before and during the pandemic regarding specific foods such as home-grown fruits and vegetables, fast-foods, home-made meals, unhealthy snacks, meat, carbohydrates, snacks between meals, late night snacks, binge eating out of control, and binge drinking alcohol; and finally, whether or not the quantity of daily meals changed during the lockdown. The third and final part of the questionnaire was related to the lifestyle changes. Respondents were asked to specify if they had any change in their smoking habits, caffeine consumption habits, weekly physical exercise engagement, and daily screen time for work/study.

Statistical Analysis

The data was represented as the number of respondents and percentages of total sample. The statistical analysis was computed via the IBM-SPSS 21® software. Spearman correlation was calculated in order to compute the association between several different variables. The Chi-Square Test of Independence was performed to assesses associations between categorical... while McNeman analysis was used to examine the difference between categorical variables before and during the COVID-19 emergency. Results were considered significant for p value < 0.05. The reliability was assessed through Cronbach’s α. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for before and during pandemic parameters were 0.667 and 0.736 respectively. The final collected responses were also validated through Pearson correlation against the total score where the results showed significant correlations (p<0.05). Multivariate linear regression analysis was performed to identify the factors related to behavior during pandemic where the independent variables studied were age, gender, marital status, education level, field of study and family income.

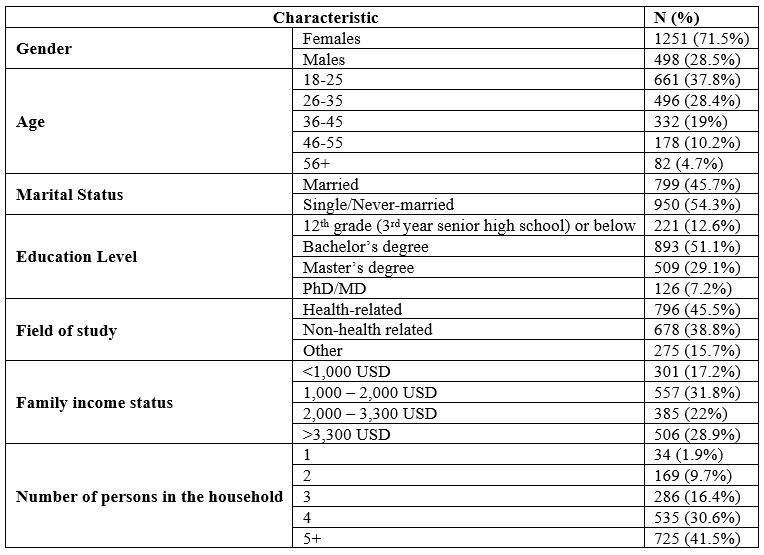

Table 1: The socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

Results

The socio-demographic details of the respondents are shown in table 1. Of the 1,749 participants, 61.9% were living in large cities, whereas only 38.1% were living in rural villages during the pandemic. 91.4% of the total respondents were bound to the restrictive measures of the lockdown set by the government, and thus were staying at home for a longer time.

Results of this study show that the lockdown had positive and negative impacts on eating habits. On the one hand, it increased the consumption of home-made foods, reduced the consumption of fast foods and meat, while having had no impact on unhealthy snack consumption. Meanwhile, this study also showed negative effects on the dietary behaviours of some Lebanese residents, particularly by increasing the number of meals consumed daily, binge eating, and weight gain.

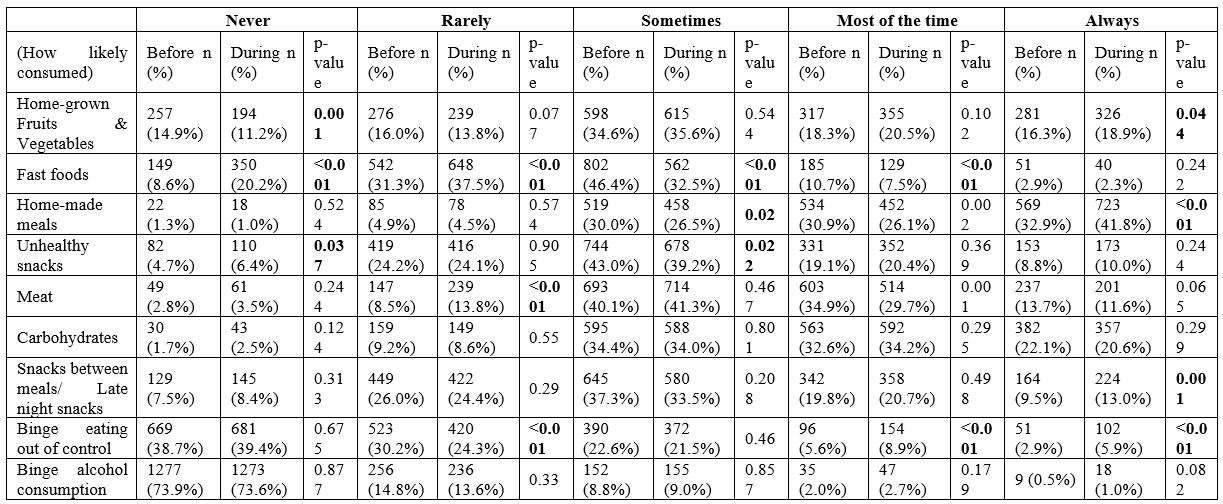

The first change in eating habits was the increase in consumption of home-grown foods. The percentage of respondents that “always” consumed home-made foods before the pandemic (33%) was less than that during the lockdown (42%) (p. <0.001). However, with regards to those who consumed home-made foods “most of the time” before the lockdown, the percentage decreased significantly from 30.9% to 26.1% during the lockdown (p. <0.001).

The second change in eating habits was the decrease in consumption of fast foods such as burgers, pizzas and other convenience food. Concerning its frequency, results of this study demonstrated that 20.2% answered they “never” consume fast foods during the quarantine, versus merely 8.6% “never” consuming them before quarantine (p. <0.001). Similarly, those who answered that they “rarely” consume fast foods during quarantine were 37.5%, compared to 31.3% before quarantine (p. <0.001). Finally, the group who consumed fast foods “most of the time” also declined significantly during lockdown (10.7%) compared to before the lockdown (7.5%) (p. <0.001). This data shows that the confinement had a positive effect on maintaining a healthy lifestyle by significantly decreasing the consumption of fast foods.

The confinement also reduced the consumption of meat but did not impact unhealthy snack consumption. The percentage of respondents who consumed meat “most of the time” during the lockdown (29.7%) was lower than that before the lockdown (35%) (p. <0.001). In addition, the group who reported to “rarely” consume meats during the lockdown (13.8%) were more than that before the lockdown (8.5%) (p. <0.001). Finally, when asked about how likely were they to consume unhealthy snacks such as chips, crackers, chocolate, sweets, cake, etc. respondents showed no significant difference in habits between the periods before and after the pandemic.

Among the negative impacts of the lockdown in Lebanon was the increase of the daily number of consumed meals. Almost half of the respondents (48.4%) consumed more meals during the pandemic, compared to 41.5% who had no change in their number of daily consumed meals. Only 10.1% consumed fewer meals. In specific, the respondents who reported that they “always” had frequent snacks and late-night snacks before quarantine were 9.5% compared to 13.0% during quarantine (p. <0.001). It was apparent that the increase in the number of meals was significantly higher in females versus males, 51.1% and 41.8%, respectively (p. =0.001). More males reported no change in the quantity of meals compared to females (48.3% and 39.0%), (p. =0.001). Of those who reported an increase in their daily meals, 60% (556 respondents) reported an increase by 1 or 2 meals per day and 9.0% (82 respondents) by more than 3 meals daily. However, 31.0% (288) were snacking frequently, without being able to specify the number of meals; that was the case of 19.1% of female participants and 9.9% of male participants (p. =0.001).

When asked about binge eating, 30.2% of the respondents reported that they “rarely” found themselves binge eating before quarantine, compared to 24.3% “rarely” binge eating during quarantine. Those who binged “most of the time” increased from 5.6% before the confinement to 9.0% during it. Furthermore, those who reported that they “always” binged before quarantine were only 2.9% compared to 6.0% who reported “always” binge eating during confinement (p. <0.001).

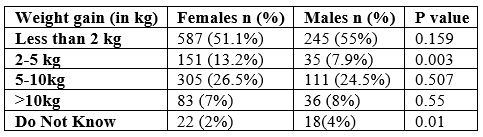

Finally, regarding weight change, 43.3% (758) of the total respondents reported gaining weight because of the lockdown, 19.2% (336) reported weight loss, and 34.2% (598) reported no weight change. Out of those who reported weight gain, 46.5% claimed to have gained between 2 and 5 kilograms; 13.2% of which were females compared to 7.9% of males (p. <0.001). Details about the increase in weight are shown in table 2.

Table 2: Weight gain distribution among females and males.

Results of the changes in eating habits are shown in table 3.

Table 3: Changes in eating habits before and during the lockdown

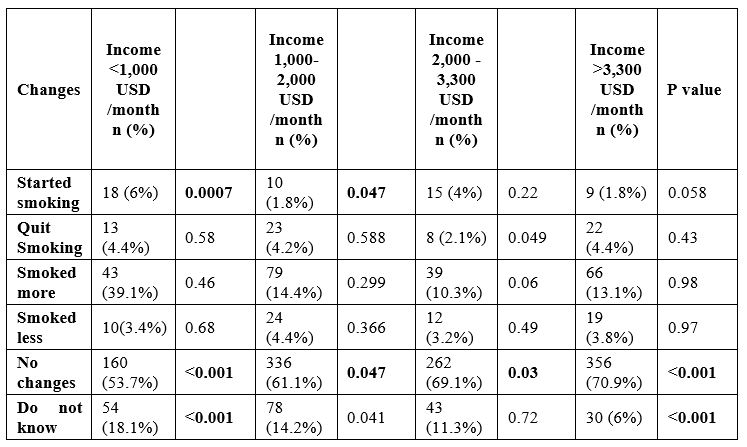

Besides the negative impact on eating behaviors, this study showed several negative impacts of the lockdown on other lifestyle factors as well, namely smoking, caffeine consumption, physical activity, and daily screen time. First, regarding smoking, most respondents (64.3%) reported no changes in their smoking habits. However, it was noteworthy that respondents with the least income (family income less than 1000USD per month) reported that they started smoking (6.0%), and this number decreased significantly with the increase in income (p. <0.001). On the other hand, 71.0% of those with highest income (family income above 3,300USD per month) had no changes in smoking habits (p. <0.001). Detailed results about changes in smoking habits are shown in table 4.

Table 4: Changes in smoking habits during the pandemic between different income groups

Aside from smoking, the lockdown negatively impacted caffeine consumption, although this effect varied between demographic groups. While more than half of all respondents (985; 56.3%) reported no changes in caffeine consumption, 11.0% of young adults aged between 18 and 25 started to drink caffeine which is by far the most significant increase in comparison with all the other age groups (p. <0.001). Regarding the field of study, respondents in the healthcare field were the most to report “drinking more caffeine” during the pandemic compared to before the pandemic (29.4% of health care workers increased their caffeine consumption during the pandemic) (p=0.025). The marital status also was correlated to caffeine consumption, where data from this study showed that 65.0% of married respondents had no change in caffeine consumption compared to 50.0% of their unmarried/single counterparts (p. <0.001). The number of single respondents consuming less caffeine due to the lockdown was significantly higher than that of married people (7.3%) (p. <0.001). Finally, 9.0% of the respondents who were single during the pandemic started to drink caffeine compared to only 4.9% of married ones (p. <0.001). When it comes to family income status, it was clear that those with the lowest incomes-initiated caffeine consumption (11.4%), which was significantly higher than those who had higher incomes (p. <0.001). On the contrary, 62.4% of respondents with the highest incomes reported no change in caffeine consumption, which was also significantly higher than those with a lower income (p. <0.001).

Changes in physical activity showed a shift towards less engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to prior to the pandemic. Mean hours spent engaging in sports significantly decreased from 2.20 hours to 1.99 hours during the pandemic (p<0.001). The mean of physical activity hours declined from 2.55 hours to 2.18 hours and from 2.05 hours to 1.90 hours for males and females respectively (p<0.001). During the pandemic, 49.1% of those aged between 26 and 35 years had no physical activity at all, while 17.0% of respondents aged above 56 years practiced a physical activity 5 days per week (p <0.001). Significantly higher percentage of female respondents had no engagement in physical activity (45.0%) compared to that of males (36.1%)(p <0.001). On the contrary, significantly more males reported exercising 5 or more days per week (12.2%) compared to females (5.6%) (p <0.001). The results also show that 48.3% of married individuals engaged in no physical activity during the pandemic, compared to 37.2% of single individuals (p <0.001).

Changes in screen time showed an increase in daily screen time for work and study during the pandemic. Mean hours for time spent in front of the screen increased from 2.20 hours before the lockdown to 3.04 hours during the lockdown, similar for both sexes (p<0.001). Mean hours for screen time increased from 2.47 hours to 3.00 hours (p< 0.001) for males; and from 2.22 hours to 3.06 hours (p<0.001) for females. Single persons are significantly more likely to spend more than 6 hours per day to study and/or work on the computer compared to married individuals (45.4% versus 34.4% respectively) (p <0.001). Moreover, 12.7% of the married individuals spent no time in front of the computer, 21.6% spent 1 to 3 hours per day on the computer compared to 5.0% and 15.8% respectively when it comes to the single individuals (p<0.001). 18.6% from the least educated group spent no time in front of the screen (p<0.001). Regarding the field of study of the respondents and time spent in front of the screen, 5.5% among those enrolled in the health field did not use the screen (p <0.001), compared to 46.5% of enrolled in health-related studied spending using the screens more than 6 hours daily (p<0.001).

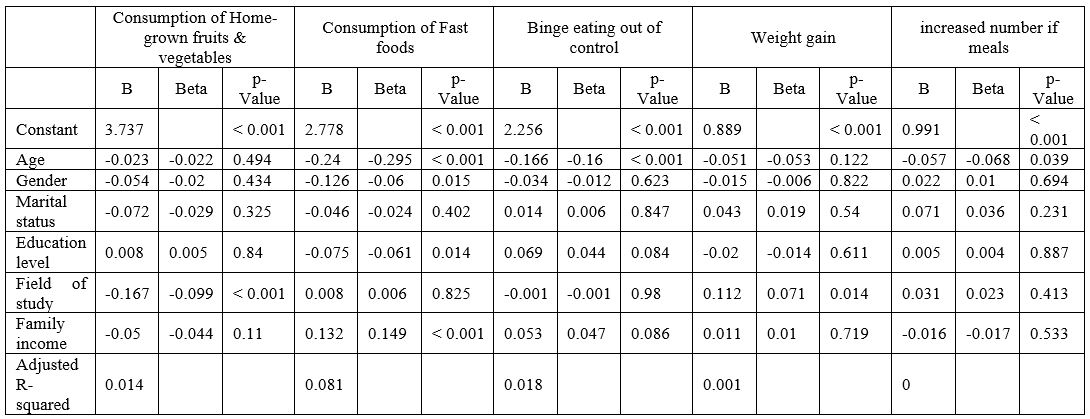

The changes in eating behaviors and lifestyle changes were examined using regression analyses. After controlling the socio-demographic characteristics such as age, gender, marital status, education level, field of study and family income, those who were more likely to consume home-grown fruits and vegetables during the pandemic (β= -0.099, p <0.001) are those in the healthcare field. Respondents who were more likely to consume fast foods were females (β=-0.06, p=0.15), the youngest age group (18-25 years) (β= -0.295, p<0.001), those with the least education (β=-0.061, p=0.14), and those with the highest income (>3,00$USD / month) (β= 0.149, p <0.001). The youngest participants in this study were most likely to binge eat out of control (β= -0.16, p<0.001), and have frequent meals throughout the day (β= -0.68, p=0.039) as well. When it comes to weight gain, those in non-health related fields of study were the most to gain weight (β=0.71, p=0.14). (Table 5)

Table 5: Change in eating habits during the pandemic.

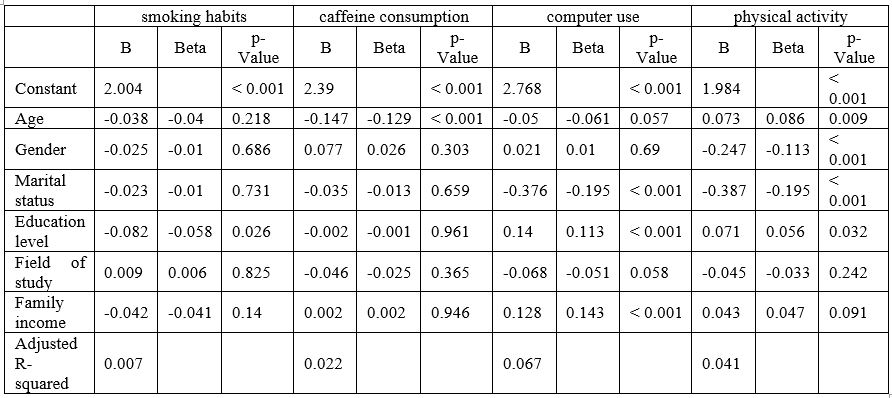

Regarding lifestyle changes, the respondents with the most change in smoking habits (β=-0.058, p=0.026) were the least educated, however, those with the most change in caffeine consumption (β=-0.129, p<0.001) were the youngest age group (18-25 years).

The participants who were more likely to spend long hours using the screen for work/study were single individuals (β= -0.195, p<0.001), those with the highest education level (β= 0.113, p<0.001), and those with the highest incomes (β=0.143, p<0.001).

Concerning physical activity, respondents who were most likely to stop engaging in any form of sports during the pandemic were the younger age groups (β=0.86, p=0.009), females (β=-0.113, p<0.001), married individuals (β=-0.195, p<0.001), and the most educated (β=0.56, p=0.032).

Table 6: Changes in lifestyle behaviors during the pandemic.

Discussion

Lebanese residents completed the questionnaire during January 2021, 10 months following the start of the pandemic lockdown in Lebanon. Their responses provide an indicator of the bigger picture taking place in the country. It is important to note, however, that the pandemic struck Lebanon at a critical time, layering above multiple crises. Thus, the results may stem from a variety of factors and may not be attributable to the effects of the pandemic alone. The panic caused by the disease and death, in addition to the limitations of individual freedom, exacerbated the tension already among civilians and created variations in usual and routine activities [21]. Hence, changes were observed during the COVID-19 pandemic regarding lifestyle and eating habits. The vast majority of this sample population was abiding by lockdown measures, practicing social distancing and staying at home most of their time. This was the case for about 3 times more females than males participating in this study.

A balanced and healthy diet is well-known to aid in sustaining immunity, and thus, is crucial for avoidance and treatment of infections caused by viruses [22]. Healthy dietary behaviors are vital, and supplementation with certain micronutrients may be helpful, in particular, for persons at risk [23]. Therefore, we can confirm that the nutritional status of an individual plays a vital role in protecting him/her against viral infections [24]. There was a considerable variety in the answers provided for the various questions regarding weight gain and frequency of snacking. For example, even though 43.0% of the participants reported gaining weight during the lockdown, 19.2% reported losing weight, and 34.2% reported no weight changes. The majority in this research reported weight gain, which is similar to data results from comparable studies conducted in Saudi Arabia [25], Kuwait [26], UAE [9], Italy [16], and Poland [27] that also reported weight gain because of the lockdown.

Likewise, although 48.4% of the sample studied reported a daily increase in the number of meals they consumed, 41.5% reported a decline in the number of consumed meals. Similarly, data results from Saudi Arabian [28], Italian [29], Danish [30], and Polish studies [12] [27] also showed that the number of daily consumed meals increased among the majority of the respondents during the lockdown. The deviation in eating habits in Lebanon was not only limited to “increasing” meal quantity and “gaining” weight, which could also be related to how each individual cope with stress, a factor that usually increases the number of meals consumed daily [31], but is not always the case.

In this study, consumption of home-grown fruits and vegetables did not change before and during the pandemic. Although many Lebanese residents moved to their villages to spend their stay-at-home time away from the city, it was assumed that home-grown produce consumption would increase, but this was not the case. This could be explained by the fact that Lebanese residents who moved to more rural areas remained functional in their work or studies. So, despite the fact that they had the chance to grow more fresh produce; they lacked the time for it.

The pandemic caused positive changes in the Lebanese population’s eating habits. Fast food consumption declined, as shown in this study, similar to data from Poland [12], yet contradicts what was seen in a similar research done in Qatar, where frequent consumption of fast food increased [20]. Moreover, meat consumption significantly declined throughout the lockdown in Lebanon, compared to before it, and home-made meals increased significantly. This is beneficial for individual as well as environmental health [32] [33]. The increase in home-made meals is similar to data results from Spain [34], in New Zealand, where respondents reported an increase in home cooking and baking from scratch [35], and in Saudi Arabia, where 85.6% of the respondents reported eating home-cooked meals on a daily basis during COVID-19 as compared to 35.6% before the lockdown [25].

Another positive outcome is the decline in the consumption of unhealthy snacks like chocolate, chips, crackers, cakes, etc. This is also comparable to data obtained from New Zealand [35], yet contradicts data from Spain that instead showed an increase in the consumption of unhealthy snacks such as salty snacks, cookies, bakery products, and chocolate. [36].

On the other hand, there were several negative effects regarding eating habits, one of which was binge eating out of control; also witnessed in a similar study conducted in Italy [37]. Another negative impact shown in this study is the increase in frequent snacking (including late-night snacks) that increased during the quarantine compared to before it, mainly among females. This might be related to increased levels of stress accompanied by quarantine and the lockdown, which is consistent with several global studies that shed light on emotional eating during the lockdown [37]. The increase in snacking was also observed in the UK, a similar study confirms [10].

When it comes to lifestyle changes; UK studies showed inconsistent data. One study showed an increase in smoking during the lockdown, explained by the fact that people resorted to smoking to kill time and because of stress and boredom [38], Meanwhile, another study showed that the increase in smoking was statistically insignificant; and interestingly, it showed that smoking cessation and quit attempts increased during the pandemic compared to before it [39]. In New Zealand, around half the respondents of one study, who usually smoke on a daily basis, reported increasing their smoking consumption, with an average increase of 6 cigarettes per day, due to feelings of loneliness and boredom [40]. In Lebanon, although 64.3% reported no changes in smoking habits, 13.2% reported smoking more during the quarantine, which is similar to most global data. These results were mostly significant in lower-income families. This can be explained by the fact that those with the least income were the most stressed because of the pandemic coinciding with the financial crisis, causing them to resort to smoking.

Concerning caffeine consumption, even though around half the respondents reported no change in caffeine consumption, 25.7% reported increasing their caffeine intake during the lockdown. The increase in caffeine consumption was mostly reported, unfortunately, in young adults aged 18 to 25; this is contradictory to a study conducted in the USA that showed that young adults aged 18-35 years had a decline in their caffeine intake compared to older adults [41]. Likewise, a same increase in caffeine consumption was observed in Lebanese healthcare professionals, unmarried individuals, or those with the least income. The concern is that caffeine consumption, when excessive, is associated with an increased risk in cardiovascular disease [42]. Similar to the case of smoking, populations that were probably stressed the most resorted to increasing their caffeine consumption; this may be explained by the increase in overwhelmed healthcare workers, as well as the population with the least income.

A life aspect that was significantly affected by COVID-19 pandemic is engagement in physical activity. Other studies showed that shutting down gyms and limiting ‘non-essential’ travel may result in a decline in overall physical activity [43]. In a study conducted in the UAE, 38.5% of respondents did not engage in physical activity during lockdown [9]. In India, people who exercised more than 3 times a week went down radically from 42% of total participants before the lockdown, to 22% of participants during the lockdown [44]. In Spain, the number of participants that exercise decreased significantly, as well as the time spent exercising [34]. The same applies to China, where around 60% of adults had no engagement in proper physical activity [45]. These results are consistent with results from this Lebanese study, where those who did not engage in sports before the COVID-19 pandemic did not use this as an opportunity to start; on the contrary, those who were physically active had a decrease in terms of days exercised weekly. Respondents who do not exercise at all increased from 31.4% before the lockdown to 40.6% during lockdown. Both males and females had a decline in mean hours of exercise, however, females were more likely to skip exercising than males with 45% of them engaging in no physical activity whatsoever compared to 36% of all males. On the other hand, males grasped the opportunity to exercise on most days significantly more than females. This shows that males were more dedicated to exercise compared to females. This might be due to the fact that females were busy with their children, family, house and/or work, during the total lockdown sparing no time to invest in sports. This is also shown in the correlation between marital status and physical activity; where significantly more married individuals had no physical activity at all compared to singles. When it comes to age, adults aged 26 to 35 were the largest group to report not exercising at all, which can be due to the heavy workload “from home” and getting accustomed to a new norm which left them too busy to exercise. However, luckily, the age group that significantly exercised the most was the eldest group, aging above 56. This data is similar to a recent study conducted in Belgium where individuals above 55 were the most age group to engage in frequent physical activity [46].

Finally, the increase in screen time during the lockdown was consistent with Chinese [45] [47], German [48] and several global studies. In Lebanon, this study showed that those who spent 6 or more hours per day on their computer to work or study increased from 16.7% before to 40.4% during the pandemic. Those who didn’t use the computer for work and study declined from 21% before the pandemic to 8% during the pandemic. Even mean hours for daily screen time increased significantly. Single individuals spent more time working and/or studying on-screen compared to married individuals, which hints that single people had more time on their hands to use their computers. Moreover, the least educated demographic was the least to use screens, which is expected. At last, half of those in the health-related field were spending more than 6 hours on their computers. Thus, healthcare professionals may have found themselves spending a lot of time on screen to stay up-to-date with all the new medical knowledge. Increased digital screen time during the pandemic is no surprise, since the lockdown obliged the whole world to “work-“and “study-from-home”. We expect that daily screen time will maintain pandemic highs into the “new normal”. The problem is that prolonged hours in front of screens has been proven to lead to several risks, of which are myopia [49], depression [50], extensive feelings of sleepiness [51], and an overall decline in mental, general health [52], and overall wellbeing [53].

Health authorities and policy makers in Lebanon have conducted awareness campaigns regarding several aspects related to COVID-19. First, multiple campaigns were designed to educate people on the prevention of virus transmission, mainly by explaining what measures are recommended to contain the virus and limit its spread. Furthermore, health authorities have shed light on what to do in case of infection; all measures concerning isolation and what to do during the infection phase were clearly communicated to the public. Finally, health policy makers also held campaigns on vaccinations for COVID-19, where they educated people on the importance of getting vaccinated to prevent infection and build immunity, which in turn reduces the community spread.

In light of this study, we recommend that health policy makers take into consideration the dietary and lifestyle changes caused by the lockdown measures and pro-actively raise awareness of the health implications caused by the lockdown. We suggest having campaigns that highlight how the increase in weight, food consumption and frequent snacking could lead to obesity. According to the CDC, obesity, as well as a lack of physical activity impose several health risks such as an increased incidence of type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and atherosclerosis (where fatty deposits narrow the arteries), which in turn can lead to coronary heart disease and stroke. [2]

Moreover, an increase in smoking causes lung disease by damaging the airways and the small air sacs (alveoli) found in the lungs. Lung diseases caused by smoking include COPD –Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease-, which includes emphysema and chronic bronchitis. Cigarette smoking causes most cases of lung cancer. Health policy makers should highlight these risks to the public in order to prevent the dangerous effects of smoking. When it comes to caffeine consumption, we suggest that people should be aware that a high caffeine intake can cause insomnia, restlessness, nervousness, stomach irritation, nausea, an increased heart rate and respiration.

This study has several limitations. One limitation is the simultaneous crises that struck the Lebanese population. The pandemic coincided with a major financial crisis and a significant devaluation in the local currency. This led to an increase in emotional stress that could impact the eating habits and lifestyle of the population. Thus, the results of this study may be multi-factorial. Another limitation to this study is the online nature of the questionnaire. Having been distributed via social media, this may lead to a bias in responses by social media users with internet connections within the researchers' immediate and expanded social networks. Therefore, there could be sections of populations that were not reached because they have no internet access.

The strengths of this study are mainly its number of participants and their diversity, and it being the first of its kind in Lebanon. Having a sample with a large number (n=1749) gives a more representative figure of the whole population. Also, the demographic characteristics of the sample show that the participants were diverse in age, gender, financial status, field of study, education level, and marital status. Finally, this is the first study in Lebanon to assess the impact of the confinement measures on eating behaviors and lifestyle changes in the country.

Conclusion

This study measured changes in dietary behaviour and eating habits in the Lebanese population during quarantine measures imposed to contain the COVID-19 pandemic. It met its primary and secondary objectives where it demonstrated that staying at home for a long period of time cannot be deemed simply totally “positive” nor “negative” when it comes to dietary behaviour. This study showed that the quarantine promoted negative habits like increased number of daily meals consumed increased smoking and caffeine consumption in certain populations, and weight gain in almost half of the respondents. However, the quarantine, also promoted positive habits like a decline in unhealthy snacking and fast-food consumption. It is recommended that health policymakers consider these results when setting future policies pertaining to extended quarantine measures. It is also recommended that policymakers as well as individuals of the community be aware of the negative effects of stay-at-home orders on their individual as well as the community’s health, as shown in this study. Further studies are needed to examine these variables in the Lebanese population without the coinciding effects of the financial crisis.

Acknowledgement

The authors would like to thank every individual who participated in this study.

Authors’ contribution

CR and SS designed the study. CR and AK carried out the data collection and interpreted the data. CR and SS drafted the manuscript. All authors have approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Competing Interest

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- WHO, "World Health Organization," 2020.

- CDC, "Centers for Disease Control," 2020.

- Atalan A, "Is the lockdown important to prevent the COVID-19 pandemic? Effects on psychology, environment and economy-perspective," Annals of medicine surgery, 2020; 56: pp. 38-42.

- Chen P, Mao L, Nassis GP, Harmer P, Ainsworth BE, Li F, "Coronavirus disease (COVID-19): The need to maintain regular physical activity while taking precautions," Journal of Sports and Health Science, 2020; 9(2): pp. 103-104.

- Wang C, Vine S, Hsiao A, Rundle A, Goldsmith J, "Weight-related behaviors when children are in school versus on summer breaks: does income matter?" Journal of School Health, 2020.

- Kinsey EW, Hammer J, Dupuis R, Feuerstein-Simon R, Cannuscio C, "Planning for Food Access During Emergencies: Missed Meals in Philadelphia," American Journal of Public Health, 2020; pp. 781-783.

- Marsh S, Mhurchu CN, Maddison R, "The non-advertising effects of screen-based sedentary activities on acute eating behaviours in children, adolescents, and young adults. A systematic review," Appetite, 2013; pp. 71-73.

- Ammar A, Brach M, Trabelsi K, Chtourou H, Boukhris O, Masmoudi L, et al., "Effects of COVID-19 Home Confinement on Eating Behaviour and Physical Activity: Results of the ECLB-COVID19 International Online Survey," Nutrients, 2020; 12(6): p. 1583.

- Ismail LC, Osaili T, Mohamad M, Marzouqi AA, Jarrar A, Jamous DA, et al., "Eating Habits and Lifestyle during COVID-19 Lockdown in the United Arab Emirates: A Cross-Sectional Study," Nutrients, 2020; 12(11): p. 3314.

- Robinson E, Boyland E, Chisholm A, Harrold J, Maloney NG, Marty L, et al., "Obesity, eating behavior and physical activity during COVID-19 lockdown: A study of UK adults," Appetite, 2021; 156(0195): p. 6663.

- Robinson E, Gillespie S, Jones A, "Weight‐related lifestyle behaviours and the COVID‐19 crisis: An online survey study of UK adults during social lockdown," Obesity, Science and Practice, 2020; 6(6): pp. 735-740.

- Błaszczyk-Bębenek E, Jagielsk P, Bolesławska I, Jagielska A, Nitsch-Osuch A, Kawalec P, "Nutrition Behaviors in Polish Adults before and during COVID-19 Lockdown," Nutrients, 2020; 12(10): p. 3084.

- Górnicka M, Drywień ME, Zielinska MA, Hamułka J, "Dietary and Lifestyle Changes During COVID-19 and the Subsequent Lockdowns among Polish Adults: A Cross-Sectional Online Survey PLifeCOVID-19 Study," Nutrients, 2020; 12(8): p. 2324.

- Kriaucioniene V, Bagdonaviciene L, Rodríguez-Pérez C, Petkeviciene J, "Associations between Changes in Health Behaviours and Body Weight during the COVID-19 Quarantine in Lithuania: The Lithuanian COVIDiet Study," Nutrients, 2020; 12(10): p. 3119.

- Zeigler Z, Forbes B, Lopez B, Pedersen G, Welty J, Deyo A, et al., "Self-quarantine and weight gain related risk factors during the COVID-19 pandemic," Obesity, Reseach & CLinical Practice, 2020; 14(3): pp. 210-216.

- Di Renzo L, Gualtieri P, Pivari F, Soldati L, "Eating habits and lifestyle changes during COVID-19 lockdown: an Italian survey," Journal of translational medicine, 2020; 18(229).

- MOPH, "Ministry of Public Health," 2021.

- Rusi J, Moubadda A, Maatouk I, "Potential impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health outcomes in societies with economic and political instability: case of Lebanon," Mental Health Review Journal, 2020; 25(3): pp. 215-219.

- Flanagan E, Beyl R, Fearnbach N, Altazan A, Martin C, Redman L, "The Impact of COVID‐19 Stay‐At‐Home Orders on Health Behaviors in Adults," Obesity, 2020; 29(2): pp. 438-445.

- Ben Hassen T, El Bilali H, Allahyari M, "Impact of COVID-19 on Food Behavior and Consumption in Qatar," Sustainability, 2020; 12(17): p. 6973.

- Brooks S, Webster R, Smith L, Woodland L, Wessely S, Greenberg N, et al., "The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence," Lancet, 2020; 395(10227): pp. 912-920.

- Jayawardena R, Sooriyaarachchi P, Chourdakis M, Jeewandara C, Ranasinghe P, "Enhancing immunity in viral infections, with special emphasis on COVID-19: A review," Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome, 2020; 14(4): pp. 367-382.

- Muscogiuri G, Barrea L, Savastano S, Colao A, "Nutritional recommendations for CoVID-19 quarantine," Perspective, 2020; 74: pp. 850-851.

- Beck M, Handy J, Levander O, "Host nutritional status: the neglected virulence factor," Trends in microbiology, 2014; 12(9): pp. 417-423.

- Alhusseini N, Alqahatni A, "COVID-19 pandemic’s impact on eating habits in Saudi Arabia," Journal of Public Health Research, 2020; 9(3): p. 1868.

- Almughamis N, AlAsfour S, Mehmood S, "Poor eating habits and predictors of weight gain during the COVID-19 quarantine measures in Kuwait: a cross sectional study," F1000Research, 2020; 9(914).

- Sidor A, Rzymski P, "Dietary Choices and Habits during COVID-19 Lockdown: Experience from Poland," Nutrients, 2020; 12(6).

- Aljohani NE, "The effect of the lockdown for the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic on body weight changes and eating habits in Saudi Arabia," Journal of the Saudi Society for Food and Nutrition, 2020; 13(1): pp. 103-113.

- Scarmozzino F, Visioli F, "Covid-19 and the Subsequent Lockdown Modified Dietary Habits of Almost Half the Population in an Italian Sample," Foods, 2020; 9(5): p. 675.

- Giacalone D, Bom Frost M, Rodríguez-Pérez C, "Reported Changes in Dietary Habits During the COVID-19 Lockdown in the Danish Population: The Danish COVIDiet Study," Frontiers in Nutrition, 2020; 7.

- Oliver G, Wardle J, "Perceived Effects of Stress on Food Choice," Physiology and behavior, 1999; 66(3): pp. 511-515.

- Cheah I, Shimul AS, Liang J, Phau I, "Drivers and barriers toward reducing meat consumption," Appetite, 2020; 149(104636).

- Mills S, Brown H, Wreiden W, White M, Adams J, "Frequency of eating home cooked meals and potential benefits for diet and health: cross-sectional analysis of a population-based cohort study," International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 2017; 14.

- Sánchez-Sánchez E, Ramírez-Vargas G, Avellaneda-López Y, Orellana-Pecino JI, García-Marín E, Díaz-Jimenez J, "Eating Habits and Physical Activity of the Spanish Population during the COVID-19 Pandemic Period," Nutrients, 2020; 12(9): p. 2826.

- Gerritsen S, Egli V, Rajshri R, Haszard J, De Backer C, Teunissen L, et al., "Seven weeks of home-cooked meals: changes to New Zealanders’ grocery shopping, cooking and eating during the COVID-19 lockdown," Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 2020.

- Pérez-Rodrigo C, Gianzo Citores M, Hervás Bárbara G, Ruiz-Litago F, Casis Sáenz L, Arija V, et al., "Patterns of Change in Dietary Habits and Physical Activity during Lockdown in Spain Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic," Nutrients, 2021; 13(2): p. 300.

- Cecchetto C, Aiello M, Gentilia C, Ionta S, Osimo SA, "Increased emotional eating during COVID-19 associated with lockdown, psychological and social distress," Appetite, 2021; 160(105122).

- Grogan S, Walker L, McChesney G, Gee I, Gough B, Cordero M, "How has COVID-19 lockdown impacted smoking? A thematic analysis of written accounts from UK smokers," Psychology & Health, 2020.

- Jackson SE, Garnett C, Shahab L, Oldham M, Brown J, "Association of the Covid-19 lockdown with smoking, drinking, and attempts to quit in England: an analysis of 2019-2020 data," medRxiv, 2020.

- Gendall P, Hoek J, Stanley J, Jenkins M, Every-Palmer S, "Changes in Tobacco Use During the 2020 COVID-19 Lockdown in New Zealand," Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 2021.

- Siobhan M, Qiuchen Y, Behr H, Deluca L, Schaffer P, "Self-reported food choices before and during COVID-19 lockdown," Medrxiv, 2020.

- Ang Zhou EH, "Long-term coffee consumption, caffeine metabolism genetics, and risk of cardiovascular disease: a prospective analysis of up to 347,077 individuals and 8368 cases," The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 2019; 109(3): pp. 509-516.

- Ding D, Del Pozo Cruz B, Green M, Bauman A, "Is the COVID-19 lockdown nudging people to be more active: a big data analysis," British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2020; 54: pp. 1183-1184.

- Kumar M, Dwivedi S, "Impact of Coronavirus Imposed Lockdown on Indian Population and their Habits," International Journal of Science and Healthcare Research, 2020; 5(2).

- Qin F, Song Y, Nassis GP, Zhao L, Dong Y, Zhao C, et al., "Physical Activity, Screen Time, and Emotional Well-Being during the 2019 Novel Coronavirus Outbreak in China," International Journal of Environmental research and public health, 2020; 17(14): p. 5170.

- Constandt B, Thibaut E, De Bosscher V, Scheerder J, Ricour M, Willem A, "Exercising in Times of Lockdown: An Analysis of the Impact of COVID-19 on Levels and Patterns of Exercise among Adults in Belgium," International Journal ofEnvironmental research and public health, 2020; 17(11): p. 4144.

- Qiu W, Qiu H, Heng Z, Peng Y, Wenwen W, Xing C, et al., "Prevalence of Insufficient Physical Activity, Sedentary Screen Time and Emotional Well-Being During the Early Days of the 2019 Novel Coronavirus (COVID-19) Outbreak in China: A National Cross-Sectional Study," SSRN Electronic Journal, 2020.

- Schmidt S, Anedda B, Burchartz A, Eichsteller A, Kolb S, Nigg C, et al., "Physical activity and screen time of children and adolescents before and during the COVID-19 lockdown in Germany: a natural experiment," Scientific Reports, 2020; 10.

- Wong CW, Tsai A, Jonas JB, Ohno-Matsui K, Chene J, Ang M, et al., "Digital Screen Time During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Risk for a Further Myopia Boom?" American Journal of Ophthalmology, 2021; 223: pp. 333-337.

- Hodes LN, Thomas KG, "Smartphone Screen Time: Inaccuracy of self-reports and influence of psychological and contextual factors," Computers in human behavior, 2021; 115(106616).

- Majumdar P, Biswas A, Sahu S, "COVID-19 pandemic and lockdown: cause of sleep disruption, depression, somatic pain, and increased screen exposure of office workers and students of India," The Journal of Biological and Medical Rhythm Research, 2020; 37(8): pp. 1191-1200.

- Colley RC, Bushnik T, Langlois K, "Exercise and screen time during the COVID-19 pandemic," Statistics Canada. Health Report, 2020; 31(6): pp. 3-11.

- Stieger S, Lewetz D, Swami V, "Emotional Well-Being Under Conditions of Lockdown: An Experience Sampling Study in Austria During the COVID-19 Pandemic," Journal of Happiness Studies, 2021.