Granulomatous Mucormycosis with Excellent Response to Treatment, Report of a Case and Review of Literature

Fariba Binesh, Parisa Madahian Najafabadi, Sara Mirhosseini, Kazzem Gheybi*

Department Of Pathology, Shahid Sadoughi University Of Medical Sciences,Iran

Hematology and Oncology Research Center, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences and Health Services,

Iran

Department of Otolaryngology, Shahid Sadoughi University of Medical Sciences, Iran

Medical student, Shahid Sadoughi University Of Medical Sciences, Iran

Department of Allied Health and Human Performance, University of South Australia, Australia

Received Date: 14/01/2021; Published Date: 27/01/2021

*Corresponding author: Kazzem Gheybi, 5Department of Allied Health and Human Performance, Australian Centre for Precision Health, South Australia Health and Medical Research Institute, North Terrace, Adelaide 5000, South Australia. Email: mohammad_kazzem.gheybi@mymail.unisa.edu.au, kazzem.gheybi@sahmri.com

Abstract

Introduction: Mucormycosis is an uncommon fungal infection. Here we report a patient with granulomatous paranasal sinuses Mucormycosis.

Case report: A 64-year-old diabetic male presented with a history of right cheek swelling and numbness for five months before. A computed tomography (CT) scan showed a mass in his right maxillary sinus with destruction of anterior wall of the right maxillary sinus and alveolar ridge. The patient underwent Caldwell-Luc surgical resection of the right maxillary sinus mass and the histological examination of the H&E and PAS stained slides confirmed the diagnosis of granulomatous mucorrmycosis. After treatment with amphotericin B and caspofungin, the patient was recovered.

Conclusion: Although mucormycotic is known to be an infection with poor prognosis, the presented patient responded well to treatment.

Keywords: Mucormycosis; Granuloma; Maxillary sinus

Introduction

Granulomatous reaction is an inflammatory reaction, which is defined by the presence of granulomas in the tissue. A granuloma is characterized by the accumulation of epithelioid cells together with a variety of multinucleated giant cells. The causes of granulomas are very diverse and many infectious and non-infectious disorders could cause granuloma formation [1]. Fungal infections are mostly associated with suppurative reactions however, they may be seen with granulomatous response in the tissue. Although fungal infections are relatively common in humans, the formation of a granulomatous mass is a less frequent event. On the other hand, among the fungi, Aspergillus is the most common cause of granulomatous reaction [2]. Mucormycosis is a disease caused by an invasive fungus from order Mucorales and it is primarily transmitted through inhalation of spores, orally or inoculation in a trauma [3]. It usually occurs in patients who have compromised immune system such as uncontrolled or poorly controlled diabetic patients or malignancies. Neutrophils play a pivotal role in protecting the body against this infection; therefore neutropenic patients are at risk of Mucor mycosis [4]. It has been shown that malignancy is the most prevalent associated comorbidity in the developed societies whereas, diabetes is the most important comorbidity in the developing societies in Mucor cases [5,6]. The classification of Mucormycosis is based on its anatomical location and includes rhino cerebral, pulmonary, cutaneous, gastrointestinal, disseminated, or uncommon presentations [7]. In fact, the clinical manifestation is mainly relevant to the underlying disease, as the diabetic patients are more likely to have the rhino-orbital-cerebral Mucormycosis, and the patients with hematological malignancies and soft tissue trauma are more likely to suffer from the sino-pulmonary form and soft tissue Mucormycosis respectively [8]. One of the hallmarks for diagnosis of Mucormycosis in any anatomical region is the invasion into the vessels and the subsequent tissue infarction [9]. Although the prognosis of Mucor mycosis is generally poor, here we report a case of Mucor mycosis that was treated successfully.

Case Report

A 64-year-old man presented to a local clinic with a history of right cheek swelling and numbness for one month (day 1). His medication included Aspirin, Clopidogrel, Metoprolol and Losartan for cardiovascular disease, Insulin and Repaglinide for diabetes and Sulfasalazine for inflammatory bowel disease. After 15 days his condition deteriorated, and he developed fever and chills. He was admitted to a rural hospital because of these symptoms in addition to high uncontrolled blood sugar and fever. After the primary work-up, controlling his blood sugar and empirical antibiotic administration, he was discharged without diagnosing the cause of his cheek swelling. Although the fever was subsided, the patient still suffered from swelling of his right cheek and after 102 days was transferred to the central hospital in Yazd city, Iran for more investigations (day 117).

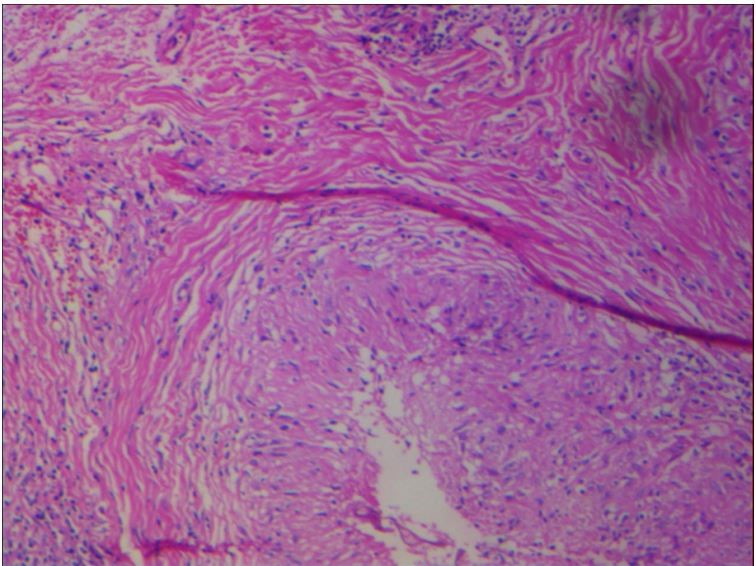

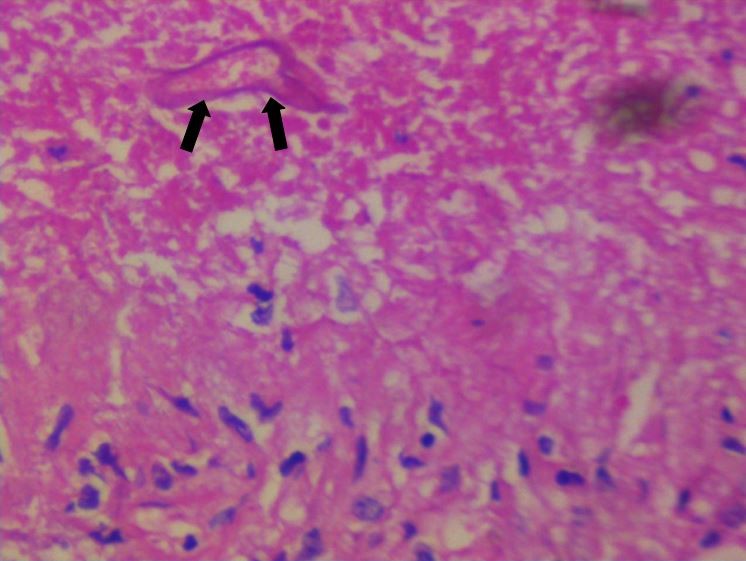

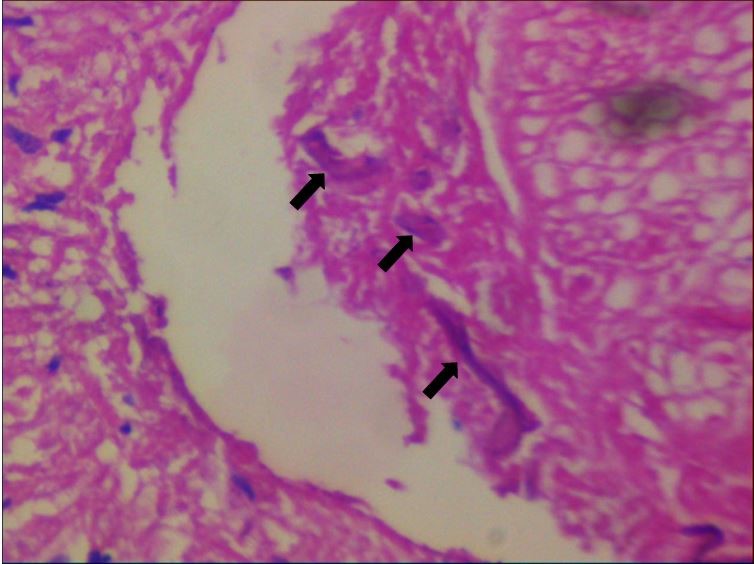

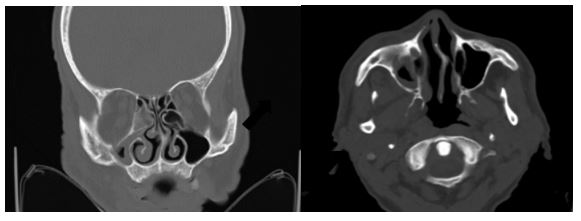

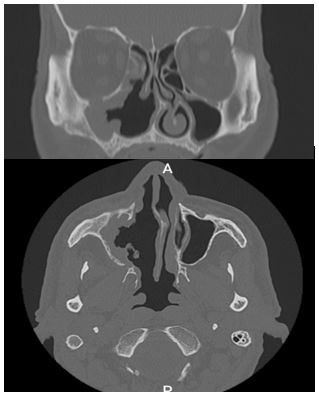

He had been well otherwise and denied any history of hemoptysis, weight loss, fever, pain in his face, nasal congestion, epistaxis or postnasal discharge. In the general physical examination, the patient was an alert and conscious male. There was no evidence of cyanosis, clubbing and peripheral lymphadenopathies. Nasal examination revealed a normal colored mucosa without evidence of necrosis, hemorrhage and septal deviation. Mucosa of the mouth and pharynx were normal. Eyes movements in all directions were unremarkable. Ears examination was normal. The laboratory results were normal except for an Erythrocyte Sedimentation Rate (ESR) of 90 mm/hr and a hyperglycemic profile. A paranasal CT scan revealed mucosal thickening in the right maxillary sinus with destruction of the anterior wall of right maxillary sinus and alveolar ridge that was in favor of neoplastic lesion. In addition, mucosal thickening in the left maxillary sinus, ethmoidal air cells and left sphenoidal sinus could be observed. No abnormality in bilateral orbits was detected. A chest X-ray showed no abnormalities. The patient underwent Caldwell-luc surgical resection of the right maxillary sinus and the specimen was sent to the pathology ward. Histological examination of the H&E stained slides demonstrated that the sinus mucosa was infiltrated by a necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. The granulomas were composed of epithelioid cells and there were scattered multinucleated giant cells. Among some of the granulomas, there were a few ribbons like and broad non-septate hyphae that showed positive reaction in PAS stain (Figures 1-3) which helped establishing the diagnosis of granulomatous Mucor mycosis. Finally, after the treatment with Liposomal Amphotericin B (150 mg/day) and Caspofungin (70 mg/day) for six weeks, the patient was recovered. The creatinine level was monitored and ranged between 0.9-1.2 mg/dL during the treatment period.

a)

b)

c)

Figure 1: (a,b,c) show necrotizing granulomatous inflammation. The granulomas are composed of epithelioid cells. Among the granuloma there are a few ribbon-like and broad non-septate hyphae (black arrows).

Figure 2: A paranasal CT scan revealed mucosal thickening in the right maxillary sinus with destruction of anterior wall of right maxillary sinus and alveolar ridge.

Figure 3: A post treatment CT scan reveals post-operative change in the right osteomata complex and right maxillary sinus with remarkable recovery of primary lesion.

Table 1: studies that reported granulomatosis Mucor mycosis cases in the literature.

Discussion

Mucor from the Mucoraceae family causes an opportunistic and rapidly progressive infection which has a high mortality rate [10]. Although more than half of Mucormycosis cases have no underlying cause, diabetes is the most common cause for this infection [11]. Recently studies have reported the disease in Covid-19 survivors after steroid therapy [12,13]. Mucormycosis have rarely been reported to cause a granulomatosis formation and since angioinvasion is a common phenomenon in Mucormycosis it is likely to be clinically and pathologically confused with malignancy [14]. The presence of a granuloma in the tissue indicates a good immune response and a good prognosis[15]. Ten cases of granulomatosis Mucormycosis have been reported so far from which five cases could be successfully treated (Table 1). Cases with involvement of the internal organs had poor prognosis whereas, those with cutaneous infection or involvement of non-vital organs have recovered despite of delayed treatment [16]. It was reported that cases with brain Mucor infection have over 80% mortality [17]. The most common form of Mucormycosis is Rhino-facial which accounts for almost one-third of the cases while, rhinomaxillary form is the most prevalent in patients with diabetes [18,19]. Histological studies have shown that Mucoraceae family tend to adhere to endothelial cells to initiate their angioinvasion [20] and the their receptor on the endothelial cells is being regulated by glucose [21]. That’s one of the explanations for the presence of Mucormycosis in diabetic patients.

Diagnosis of fungal infections is usually based on culture however, in many cases it is not performed because the clinical features are non-specific, and clinicians would not consider it as a differential diagnosis and sometimes it is mistaken for bacterial sinusitis because of the similarity of the symptoms [22]. At first, the mucosa is erythematous and it gradually turns to purple. As the process of necrosis begins, it becomes black. If a black scab or bloody discharge was observed in a susceptible patient, the differential diagnosis of Mucormycosis must be considered by the clinicians [23], although in many patients the necrotic ulcer is not evident and makes it difficult to diagnose [23]. The radiologic findings usually show nodular mucosal thickening which is not helpful in establishing the diagnosis of Mucormycosis. However Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is stated to be useful in differentiating Mucor infection from chronic bacterial sinusitis [24]. Mucosal thickening which was observed in the CT scan of this patient, has previously found to be more common in Mucormycosis in comparison to bacterial infection [25]. Raised ESR has been reported in granulomatous Mucormycosis cases previously, but there is no specific serum marker for the infection [19]. Non-infectious inflammatory diseases, such as malignancies and ophthalmopathies should be considered in the differential diagnosis of Mucormycosis [26]. Histopathologic examination with special stains (PAS and Grocott methenamine silver) is needed to achieve a definite diagnosis which requires a longer staining time for Mucorales in comparison to other fungi [27]. Treatment of Mucormycosis includes surgical removal of the necrotic tissue, use of antifungal drugs, and correction of the underlying disease. Some studies have shown that extensive surgery does not increase the survival. Amphotericin B is the best antifungal agent for Mucormycosis [28] but reports have shown cured cases with other anti-fungal agents [29]. Caspofungin can increase the efficacy of Amphotericin B, although [30]. it hasn’t shown to be useful for treatment of Mucor cases when used alone.

Conclusion

Early diagnosis with prescription of appropriate antifungal drugs and surgical debridement is essential, in addition to the site of infection are important in the prognosis of Mucor mycosis. Fortunately, the current case could be recovered successfully.

Contributions: All the authors contributed in the preparation of this research and article.

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- Volkman HE, et al. Tuberculous granuloma formation is enhanced by a mycobacterium virulence determinant. PLoS biology, 2004; 2(11): p. e367-e367.

- Murthy JM, et al. Aspergillosis of central nervous system: a study of 21 patients seen in a university hospital in south India. J Assoc Physicians India, 2000; 48(7): p. 677-681.

- Yeung CK, et al. Invasive disease due to Mucorales: a case report and review of the literature. Hong Kong Med J, 2001; 7(2): p. 180-188.

- Prabhu RM, Patel R, Mucormycosis and entomophthoramycosis: a review of the clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2004; 10 Suppl 1: p. 31-47.

- Prakash H, et al. A prospective multicenter study on mucormycosis in India: Epidemiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Med Mycol, 2019; 57(4): p. 395-402.

- Rammaert B, et al. Mucor irregularis-associated cutaneous mucormycosis: Case report and review. Medical mycology case reports, 2014; 6: p. 62-65.

- Petrikkos G, et al. Epidemiology and clinical manifestations of mucormycosis. Clin Infect Dis, 2012; 54 Suppl 1: p. S23-34.

- Lanternier F, et al. A global analysis of mucormycosis in France: the RetroZygo Study (2005-2007). Clin Infect Dis, 2012; 54 Suppl 1: p. S35-43.

- Bannykh SI, B Hunt, F Moser. Intra-arterial spread of Mucormycetes mediates early ischemic necrosis of brain and suggests new venues for prophylactic therapy. Neuropathology, 2018; 38(5): p. 539-541.

- Hoffmann K, et al. The family structure of the Mucorales: a synoptic revision based on comprehensive multigene-genealogies. Persoonia, 2013; 30: p. 57-76.

- Dubey A, et al. Intracranial fungal granuloma: analysis of 40 patients and review of the literature. Surg Neurol, 2005; 63(3): p. 254-60.

- Monte Junior ESd, et al. Rare and Fatal Gastrointestinal Mucormycosis (Zygomycosis) in a COVID-19 Patient: A Case Report. Clin Endosc, 2020; 53(6): p. 746-749.

- Mehta S, Pandey A. Rhino-Orbital Mucormycosis Associated With COVID-19. Cureus, 2020; 12(9): p. e10726.

- Ben-Ami R, et al. A clinicopathological study of pulmonary mucormycosis in cancer patients: extensive angioinvasion but limited inflammatory response. J Infect, 2009; 59(2): p. 134-138.

- Economides MP, et al., Invasive mold infections of the central nervous system in patients with hematologic cancer or stem cell transplantation (2000-2016): Uncommon, with improved survival but still deadly often. J Infect, 2017; 75(6): p. 572-580.

- Lu X-l, et al., Primary cutaneous zygomycosis caused by Rhizomucor variabilis: a new endemic zygomycosis? A case report and review of 6 cases reported from China. 2009; 49(3): p. e39-e43.

- Mohanty N, et al., Rhinomaxillary mucormycosis masquerading as chronic osteomyelitis: A series of four rare cases with review of literature. 2012; 24(4): p. 315-323.

- Goel S, et al. Rhinomaxillary mucormycosis with cerebral extension. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol, 2009; 13(1): p. 14-17.

- Sreenath G, et al., Rhinomaxillary mucormycosis with palatal perforation: A case report. 2014; 8(9): p. ZD01.

- Ibrahim AS, et al. <em>Rhizopus oryzae</em> Adheres to, Is Phagocytosed by, and Damages Endothelial Cells In Vitro. Infection and Immunity, 2005; 73(2): p. 778.

- Liu M, et al., The endothelial cell receptor GRP78 is required for mucormycosis pathogenesis in diabetic mice. J Clin Invest, 2010; 120(6): p. 1914-24.

- Mantadakis E, G Samonis. Clinical presentation of zygomycosis. Clin Microbiol Infect, 2009; 15 Suppl 5: p. 15-20.

- Yohai RA, et al. Survival factors in rhino-orbital-cerebral mucormycosis. Surv Ophthalmol, 1994; 39(1): p. 3-22.

- Raab P, et al. Imaging Patterns of Rhino-Orbital-Cerebral Mucormycosis in Immunocompromised Patients : When to Suspect Complicated Mucormycosis. Clin Neuroradiol, 2017; 27(4): p. 469-475.

- Son JH, et al. Early Differential Diagnosis of Rhino-Orbito-Cerebral Mucormycosis and Bacterial Orbital Cellulitis: Based on Computed Tomography Findings. PLoS One, 2016; 11(8): p. e0160897.

- Cunnane MB, Curtin HD. Imaging of orbital disorders. Handb Clin Neurol, 2016; 135: p. 659-672.

- Schelenz S, et al. British Society for Medical Mycology best practice recommendations for the diagnosis of serious fungal diseases. Lancet Infect Dis, 2015; 15(4): p. 461-474.

- Davoudi S, et al. Invasive mould sinusitis in patients with haematological malignancies: a 10 year single-centre study. J Antimicrob Chemother, 2015; 70(10): p. 2899-905.

- Patil A, et al. Rhizomucor variabilis: a rare causative agent of primary cutaneous zygomycosis. 2013; 31(3): p. 302.

- Rammaert B, et al. Mucor irregularis-associated cutaneous mucormycosis: case report and review. 2014; 6: p. 62-65.

- Leong ASJAjocp. Granulomatous mediastinitis due to Rhizopus species. 1978; 70(1): p. 103-107.

- Karanth M, et al. A rare presentation of zygomycosis (mucormycosis) and review of the literature. 2005; 58(8): p. 879-881.

- Hemashettar B, et al. Chronic rhinofacial mucormycosis caused by Mucor irregularis (Rhizomucor variabilis) in India. 2011; 49(6): p. 2372-2375.

- Wang XM, et al. Pulmonary mucormycosis: a case report and review of the literature. 2016; 11(5): p. 3049-3053.

- Bharadwaj R, et al. Sclerosing mediastinitis presenting as complete heart block. 2017; 11(5): p. ED12.

- Taha R, et al. Rhino-Orbito-Cerebral Mucormycosis in Immunocompetent Young Patient: Case Report. 2018; 5: p. 207.