Equity in Access to Medical Care in Colombia: a Comparative Rawlsian Justice Perspective

Javier Eduardo Bejarano Daza*

Faculty of Economic Sciences, National university of Colombia, Bogota, Colombia

Received Date: 10/08/2022; Published Date: 31/08/2022

*Corresponding author: Javier Eduardo Bejarano Daza, Faculty of Economic Sciences, National university of Colombia, Bogota, Colombia

Abstract

Access in healthcare is considered a central element for the achievement of health equity. We comparatively analyze the determinants of access in Colombia, a middle-income country and a recent member of the OECD, in comparison with model OECD countries. This comparison makes it possible to identify successful strategies for equitable access and improving health outcomes in Colombia. In analyzing equity in access, we focus on potential access to healthcare, instead of realized access, and argue that equity in potential access is more grounded in the egalitarian justice theory of John Rawls, especially the notion of fair equality of opportunity. We conclude that policies that guarantee equal opportunities in the determinants of potential access can significantly improve equity in access, especially in developing countries such as Colombia.

Introduction

Universal access to healthcare is considered a central element for the achievement of health equity [1].

According to Andersen, equity in access is determined by the degree to which race, income level, or the level of insurance coverage determine access [2]. Further, distinguishing between the possibility of using a service if necessary, and actually using the service is necessary for measuring access; an individual needing care may face financial, organizational, social, or cultural/ethnic barriers that may limit their ability to access health services, which is different from the quality or satisfaction with the service once it is accessed. Measuring access should thus be more focused on opportunities for access, because utilization is the manifestation of those opportunities [3]. Access then refers to the means and requirements that must be met before receiving medical attention [4] and not to the measurable characteristics of the use of the services. Focusing on the opportunities for access also closely aligns with the notion of equal opportunity in egalitarian justice theory, especially the work of John Rawls.

Colombia's health system had the last structural reform in 1993, favoring the participation of the private sector as a result of the structural adjustments demanded by the international financial organizations, and adopting the suggestion of the World Bank to separate the provision and the financing. Although in 2001 the World Health Organization considered the health system in Colombia to have particularly equitable financial contributions [5] still has alarming inequity in the distribution of resources and in the determinants of potential access such as demographic, financial, social and cultural factors.

Understanding Access to Care

Access to medical care is a complex, multi-stage process that begins with the need, passes to the demand, and through to receiving medical care from providers. The need arises with the health problem. The demand, when it is decided to seek healthcare services, in turn depends on the person’s available income relative to the costs of care, perceived severity of the health problem(s), and availability of providers [6].

Recognizing its composite nature, Penchansky and Thomas (1981) unpacked the concept of access, and proposed five, more analytically manageable dimensions: availability, affordability, acceptability, accommodation, and accessibility. Availability is understood as the volume of resources in relation to customers and the type of needs; also refers to the production capacity. Affordability concerns the ability to pay for services, either directly or through health insurance. Acceptability is the extent to which service delivery is appropriate or sensitive to patients’ needs, preferences, and cultural expectations. Accommodation is related to how supply of resources is organized, e.g. appointment hours, relative to patient needs. Accessibility is understood as the geographic location, distance, and travel time to obtain health resources [7].

"Access" has also been synonymous with "use," because it is inferred that the use of health services by an individual is evidence that they have been able to access these services [3]. Nevertheless, it is important to differentiate between potential and realized access. Potential access is defined as the opportunity of access, contingent on the presence of enabling resources on both the demand (e.g., income and insurance) and supply (availability of providers and facilities) sides. Potential access thus taps into the availability and affordability dimensions of access, i.e. the conditions that need to be met before use could take place [4,7] Realized access, on the other hand, is defined as the actual use and satisfaction with healthcare services [2].

Equity in Access and the Relevance of Rawls Theory of Justice

In practice, the previous conceptualization has led to disproportionate emphasis on realized access through widespread reliance on measuring utilization levels [8]. Such emphasis masks likely greater inequalities in potential access. That is because when utilization levels are employed for measuring inequity in access, the state of potential access in the group with less utilization, while ambiguous, is plausibly much lower than in the group with greater utilization. To have a more nuanced understanding of equity in access, potential access also needs to be considered; analyzing inequity in potential access also provides a direct measure of the extent to which the health system ensures “equality of opportunity” or “equal access for equal need” [3].

To that point, John Rawls’ contractarian theory of justice provides a useful theoretical framework. Rawls's theory introduces the idea of the “original position” that sets the conditions for reaching a fair allocation of resources among free and equal citizens. Rawls refers to it as the "veil of ignorance," emphasizing that impartiality can only be achieved with the total absence of information about the effect of the resource allocation agreement on the interests of any individual or group in particular. For Rawls, a fair society is based on two essential principles, referred to as (1) the Principle of Equal Basic Freedoms and (2) the Principle of Difference. The first guarantees the rights to basic liberties. The second refers to equal opportunities i.e., privileges are not fair if they are obtained through processes that do not provide equal opportunities for all. The Difference Principle considers inequality to be justifiable only if it serves to benefit those who are disadvantaged [9].

At the individual level, it is important to note that equality of opportunity does not imply that the results are the same, since individuals have the freedom of choice to pursue different alternatives. This dimension of Rawls’ theory is consistent with the liberal egalitarian notion that behaviors are expressions of the freedom of choice to which individuals are entitled. A corollary of Rawls’ notion of justice is that measuring universal access to medical care should primarily consider the evaluation of opportunities, more than of results [10]. In other words, assessing equity in access should emphasize potential more than realized access.

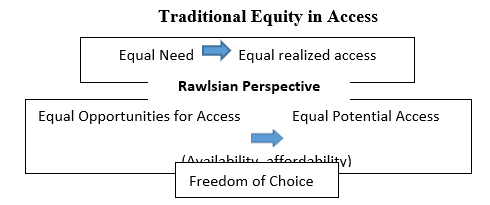

It is important to realize that potential access is “potential” mainly because it is left up to individuals to freely choose whether to realize that access, and in a society that claims to guarantee equality of opportunity, that means they could proceed to utilization with minimal impediment. For example, ideal potential access means one can, with minimal barriers, freely choose to go to the doctor or not (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Perspectives of equity in medical care access, traditionally and from a Rawlsian perspective.

To illustrate the implications of emphasizing equity in potential access at the community level, consider the following stylized example: Imagine two groups of people with comparable prevalence of diabetes, one with high income and the other with low income. While 70% of the rich group visited the doctor, 60% of the poor group did. However, taking into account the role of choice and that fact that choice is much more constrained in the poor group because of affordability, availability, and other issues (e.g., having well-informed beliefs and preferences), we would expect about 80% of the rich versus only about 65% of the poor to have the opportunity of access. More generally, if choice drives utilization to some extent, and choice is much more constrained among the poor, inequalities in potential access will always be larger than inequalities in realized access, regardless of whether those inequalities are measured on the absolute or relative scales. Because potential access incorporates elements of choice and opportunity, measuring inequity in access using potential access measures is theoretically well-grounded and will give a more accurate picture of the inequity in overall access.

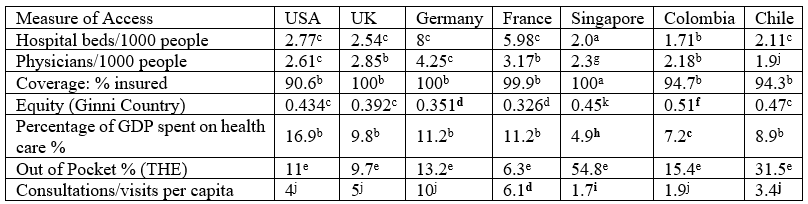

Analyzing Access in Colombia

To carry out a qualitative analysis of access to healthcare in Colombia, we consider comparing its indicators with those of countries that represents each type of health system and is a member of the OECD, with data on the following potential access variables: number of hospital beds and number of physicians per 1000 inhabitants, coverage as a percentage of the population with health insurance, and Gini index of income inequality. Likewise, we also measure realized access in terms of out-of-pocket payments, the total expenditure invested in health, and average annual visits to doctor per capita. With this, we seek to identify recommendations for better performance in Colombia and similar Latin American countries (Table 1).

The OECD standard classification in 1987 subdivided health systems into three major models: (1) voluntary (private) insurance; (2) Social Health Insurance (SHI); and (3) the National Health Service (NHS). According to the financing scheme, five models of health system exist: (1) Voluntary insurance, where citizens are free to choose whether to insure themselves; (2) Social health insurance, where workers pay contributions from their salary to a compulsory health fund; (3) The universal coverage system defined by the State scheme as the sole payer for the entire population, financed through taxes; (4) Residual programs that are funded by general taxes and targeted to specific or vulnerable populations; and (5) National Compulsory Health Insurance, where the State requires all residents to take private health insurance with a policy of minimum essential coverage, using individual resources. The State subsidizes low-income citizens and regulates the insurance market [12].

For our comparative analysis, the United Kingdom was chosen on behalf of the universal system, France and Germany as models of social health insurance, the United States representing voluntary insurance and residual programs, finally Chile and Singapore as representatives of the National Compulsory Health Insurance, resembling Colombia in several ways.

Equity in Access in Colombia

Colombia has a health system composed of three components: first, a regulatory base headed by the Ministry of Health, which is responsible for financing the system through a fund called ADRES, formerly Solidarity and Guarantee Fund (FOSYGA), which collects and distributes the resources of the system, obtained mainly from general taxes and a portion (12.5%) from payroll contributions. A second component is composed of insurers called Health Promoting Entities (Entidades Promotoras de Salud) with which it is mandatory to affiliate through the Contributive Regime (CR) for workers, or the Subsidized Regime (SR) for the population qualified as poor. These insurers can be public or private for both regimes. ADRES guarantees the financing of care for members of the CR, but also contributes to solidarity with the SR, catastrophic expenses and health promotion. The third component of the system includes healthcare providers corresponding to hospitals and professionals who receive payments from the regulatory system, in special cases of SR, by the insurer, or directly from users. This system of multiple payers has main components of the National Compulsory Health Insurance model.

According to Ayala (2014), overall access to medical care in Colombia among both insured and uninsured populations decreased in absolute terms by around 3.6% between 1997 and 2012. The uninsured were less likely by 16.1 percentage points (PP) to access medical care than members of the SR, and 22 PP less likely to have access than those of the CR; with access defined as ability to use medical care when needed (i.e., potential access).

The formal sector (workers with fixed contract) offers greater potential access than the informal sector (temporary workers); those with coverage under the CR have 5.9-PP more access, and those of the residual special regime (public teachers) have 9.7-PP more access than those in the informal sector. By socio-economic status, the highest-income stratum had 12.9-PP greater probability of access than those of low income, and 0.7-PP higher probability than those of middle income. Women had a 2.2-PP greater probability of accessing hospital services than men. There was also a 3.3-PP lower probability of access to medical health care for those who belong to the ethnic groups like aboriginals and Afro-American people of Colombia [13].

The study by Guerrero and Trujillo (2014) [14] also showed that the poor had 3.7-PP less chance of being insured under the SR, while the indigent (extremely poor) had 6.81-PP less. Being head of the family was also associated with lower probability of coverage under the SR. On the other hand, being a woman, being old, being in the rural area, and being illiterate were associated with higher odds of access.

According to the UNICO study of the World Bank (2013), there are important shortcomings in the supply of services in Colombia. About 70% of health providers are concentrated in urban areas; cities have up to 23 times more doctors than townships.

To summarize, the following are the key symptoms of inequity in potential access in Colombia:

- The uninsured have worse access than the insured.

- Of the insured, the CR provides better access than the SR, and at the same time the special regimes have better access than the former ones.

- The formal sector offers greater potential access than the informal sector.

- Households in rural areas have less access than those in urban areas.

- All of the above derives from income segregation where poor households and individuals generally have worse access to health than households and individuals with high incomes.

Equity in Access in Chile

The Chilean health system is divided into two organizational components: a public system and a private one. The private system is called the Social Health Institution (Institución de Salud Previsional-ISAPRE) and is supported by social security institutions and direct payments to private medical providers or hospitals. The public system is organized around a National Health Fund (Fondo Nacional de Salud- FONASA). Workers pay 7% of their salary, either to ISAPRE or to FONASA, with which they acquire the coverage. Members of ISAPRE can pay an additional amount for access to a greater number of services, or lower copayments. Workers affiliated with FONASA receive services through the public institutional delivery system or through private providers of their choosing. Those who have health coverage with the institutional system receive the service in municipal health clinics or public hospitals. With a co-payment that ranges between 25 and 50% of the value established by FONASA, beneficiaries can also receive service by registered private providers. The poor receive attention in the public system without co-payment. The public health system is characterized by inadequate facilities, the lack of general practitioners, specialists, and long waits. However, they respond promptly to emergencies, and it appears correlated with positive indicators on the health status of the Chilean population [13].

The results of the study by Olavarría (2005) indicate that the poor, near-poor, and people in rural areas have a lower probability of accessing health services. Women have a higher probability of access to medical care. In 2005, insurance coverage by income quintiles was 34% in FONASA and 3.1% in ISAPRE in the poorest quintile, vs. 27.1% and 54.2%, respectively, in the richest quintile. In 2009, among those in the poorest income quintile in Chile, 52.1% had free public care, 41.3% had to access with a copayment, and 6.24% used private providers [15].

The Chilean health system is focused on the hospital level and doctors exercise mostly secondary and tertiary care. There is a shortage of doctors and non-medical health professionals for the primary level of care, especially in rural areas of the country. However, there have been efforts to strengthen health systems based on Primary Health Care (PHC), as a core strategy to achieve universal access [21].

Equity in Access in Developed OECD Health Systems

United Kingdom. The general health policy in the UK is established by the Parliament, and service delivery is through the National Health Service (NHS). The system is financed from general taxes, and a small proportion of payroll tax. The NHS also receives copayments and payments from private patients. Coverage is universal. For primary care, the population must enroll in local institutions of their choice, but the offer is limited to the care of general practitioners (GPs). To reduce disparities in access, the NHS ensures resources for local areas, as well as monitoring the results for at-risk groups [19]. At the community level, general practice is addressed at local regions, where they focus on prevention and education for health, facilitating access and adequate treatments to avoid over medicalization and specialized research [20].

The access problems have been solved through a universal health model focused on primary care [20], but there are still problems with the large waiting lists to access the Health Center or "walking centers" "with the GP and the attention of general practitioners and the NHS Direct, which is a telephone consultation service [21]. The NHS of England is intervening to reduce inequalities in access to general practice services through the Operational Planning and Contracting Guide 2017-2019, and the practical resources guide - Improving access for all: reduction of inequalities in access to general practice services [22], which aims to promote access by community groups that are experiencing barriers to accessing services and help address those barriers, to as improvements in access to general practice services are implemented.

France: France and Germany represent forms of SHI, where the coverage is universal and mandatory too. According to Mossialos et al (2016) [18], in France, health policy and provision is the responsibility of the Ministry of Social Affairs, Health and Women's Rights, through compulsory health insurance and the Administration of Health and Social Affairs that have the Regional Agencies of health. The SHI is financed through payroll taxes of employees and employers by 64%, 7.5% made by employees and 13.10% made by employers, and the national income tax with a specific allowance of 36%. There is also private voluntary insurance that covers the difference between the SHI reimbursement rates through vouchers. To mitigate inequalities, all employees benefit from insurance, sponsored at 50% by the employer, for dental and vision care. The Regional Health Agencies (RHA) were created in 2009 to allow better decentralized access conditions [23].

For financial reasons, some citizens and residents currently do not find the necessary treatment, for dental or vision care. Others cannot find an independent health care provider that charges the rates reimbursed by national health insurance, especially if there are no local doctors. To solve this problem, the French model within public health insurance for all citizens, as well as for long-term residents, provides a "Vital Card", which covers the total cost of essential care for the most serious conditions (such as cancer and diabetes) and a part of the cost of other care [24].

The Carte Vitale is the health insurance card since 1998 to allow a direct health care of the SHI. Since 2008, a second generation of smart cards is being introduced, which has additional functions of an electronic health insurance card to carry electronic documents of the treatment process. Medical visits and treatments are reimbursed for social security at a rate of 70%. The remaining 30% is the responsibility of the patient. The SHI covers 100% in case of maternity, work accident and occupational disease [25].

Germany: Germany has the SHI and Private substitute Health Insurance (PHI). The states provide services through university hospitals, and the municipalities focus on primary health care and public health activities. Health spending is financed by taxes on benefits provided by SHI through sickness funds that are financed by compulsory contributions collected at 14.6% of salary. About 86% of people receive primary coverage through SHI and 11% through PHI.

There are special programs for soldiers and policemen. The provision of primary prevention services is mandatory for sickness funds. To reduce disparities, sickness funds cover the health of socially disadvantaged people (Mossialos et al. 2016) [18].

Although the costs per person in health in Germany are one third higher than the OECD average, the role of PHI is important for the need for more outpatient care centers associated with the hospital with the objective of a better balance in utilization, strengthening organizational capacity in the ambulatory care sector, with better access to low-cost care. The German SHI emphasizes equity, universal coverage and free choice, but the difference is the large number of providers and technological equipment that guarantee easy access. The SHI has implemented easy access using highly sophisticated technological equipment. Therefore, formal waiting lists and prioritization are virtually absent. Projects such as an electronic card, computerized systems for entering medical orders, remote monitoring systems and other tools can improve information and access [26].

United States: In the United States, the health system consists of several forms of insurance, including private insurance, Medicare, Medicaid and CHIP. According to a report from the US Census Bureau in 2014, public programs covered approximately 36.5% of residents: Medicare covered 16%, and Medicaid 19.5 %. In addition, 55.4% received insurance provided by the employer and 14.6% directly purchased. About 10.4% remain uninsured. Patients in U.S have relatively rapid access to specialized medical care, but paradoxically, delayed access to primary care compared with people in other developed countries.

Likewise, they report greater access problems related to cost that is the double in comparison with Australia, Canada and the UK [27].

Barriers to health services in the United States system include high cost of care, inadequate or no insurance coverage, lack of availability of services, and lack of culturally competent care. There is inequality of access to care because it varies according to race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, age, sex, disability status, sexual orientation, gender identity and residential location [28]. Disparities exist with all levels of access to care, including medical and dental insurance, which have a continuous source of care and access to primary care. Disparities also exist by geography, as millions of Americans living in rural areas lack access to primary care services due to labor shortages. Future efforts should focus on the deployment of a primary care workforce that is better geographically distributed and trained to provide culturally competent care to diverse populations [29].

To improve this situation, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has had the potential to assign incentives and create opportunities for providers to be rewarded for the delivery of patient-centered primary care. By introducing local care models, the growth in the cost of care has slowed. Primary care physicians, nursing professionals and medical assistants who provide 60% of their services in primary care codes for office visits, visits to nursing centers and home visits receive a bonus. In addition, providers in areas of resource scarcity for surgical procedures may receive an additional increase. The model called Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) or Medical Homes has several provisions that seek to strengthen the system by allowing the patient access to a regular source of primary care, stable and continuous relationships with the personal physician who runs a care team, promoting preventive services and facilitating better management of chronic conditions [30].

The specific solutions that are proposed both in healthcare systems in the US as in Colombia, include: Increasing access to the entire care process (from preventive clinical services to long-term palliative care). Both health systems, the United States and Colombia, should make the provision of primary care more frequent. According to the US Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion [31], it is intended that PCMH and team attention reduce access barriers, in addition to monitoring the increasing use of telehealth as a method of medical care.

Singapore: In Singapore, the Ministry of Health regulates the country's health system. Provides services through health and hospital networks, day care centers and nursing homes. It offers universal coverage, financed by general taxes by schemes of multiple levels and private individual savings that are used for subsidies for patients and certain institutions that provide care. The system is known as the "3M": Medisave is a mandatory health savings program where workers and employers contribute a percentage of their salaries to a personal account. MediShield is an insurance for catastrophic events of low cost and major diseases. About 10% of health expenses come from private prepaid plans that complement the MediShield. Medifund is the subsidy fund for the destitute. Patients choose the primary care physician, and it is not necessary to register [18].

The government provides access to a basic level of care and subsidizes most of the cost so that none is left without fundamental medical care, but paradoxically the system is designed so that patients contribute to the cost of care, because patients spend their own money in care beyond the basic level. To reduce inequalities, in 2007, the Ministerial Committee on Aging was established to coordinate the problems of aging in a health care system that provides older people access to care for their particular needs at an affordable price. In 2009, the Agency for Integrated Care (AIC) was established to work in the care units at the local level and to improve the level of care and carry out the integration of the primary, intermediate and long-term care sectors. All parties involved in the various levels of care with a patient must work together in a more coordinated manner. In 2012, greater subsidies were offered for intermediate and long-term care, a greater and better care infrastructure, more doctors and nurses who were added to the system with competitive remuneration [32].

The healthcare systems in both Singapore and Colombia share that universal access to medical care needs two regimes: mandatory and subsidized. While in Singapore the Medifund ensures that no Singaporean is denied access to the health system due to the inability to pay, Colombia subsidizes only half of the eligible population. This means 50% of the entire population is under SR or the SR covered. The SR and Medifund subsidies are assigned to those who really cannot afford medical care. Another major difference is that in Singapore, at least 65% of the beds of public hospitals receive large subsidies, to facilitate universal access and promote quality. In Colombia, there is no supply-side subsidy, only demand subsidy.

To avoid lack of access to healthcare in Singapore, primary care is strengthened through an extensive network of private medical clinics, which provide 80% of primary health care services, as well as 18 government polyclinics, which they provide the remaining 20%. The public sector represents 80% of public tertiary care hospitals [33,34].

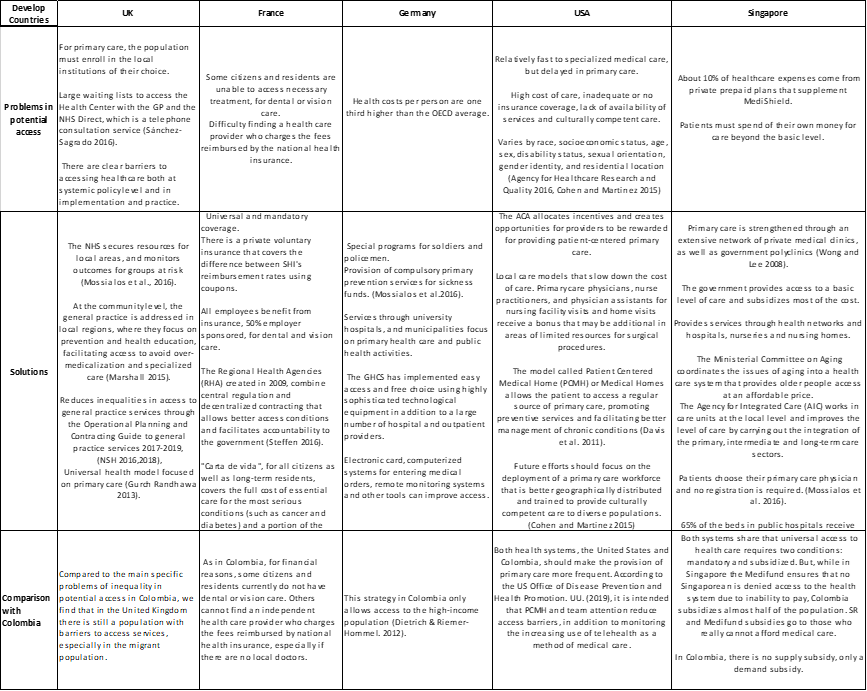

Table 2 compares the problems and solutions in potential access to health care, of each country with the situation currently in Colombia.

Table 1: Population-level indicators of potential and realized access in Colombia and select OECD countries.

Table 2: Comparison of problems and solutions in potential access to health care in OECD countries [35,36].

Lessons for Reforming Equity in Access in Colombia

In our Rawlsian analysis of access to health services, we conclude that guaranteeing equal opportunity in the determinants of potential access would improve equity and universality in access, especially through public policies that involve the level of income and health insurance for each person.

Because in Colombia, access to care varies by income, where poor households have worse access to healthcare than high-income households, it is imperative to adopt policies that break the access barriers. A clear example is how the restriction of access to care due to income differences could be broken through proven strategies of developed OECD countries, e.g., with the "vital card" for all citizens of the French model, which covers the total cost of essential care for the most serious conditions (such as cancer and diabetes) and a part of the cost of other care, when it is not accessible through insurance with resources financed by public expenditure.

Another example is reflected in the access problems shared with the United States health system, in which households in rural areas have less access than those in urban areas, which must be intervened by strengthening primary care through extension of models such as the PCMH, the RHA in France, or the provision of mandatory primary prevention services for sickness funds in Germany, which would improve potential access, by increasing equal opportunities in variables such travel time, times of appointment throughout the day, and waiting time. The evidence suggests that these strategies, as well as universal coverage, can return substantial benefits by improving affordability and availability.

In Colombia, the adoption of the strategies described above would require a change in the redistribution of the subaccounts of the Social Protection Fund (ADRES), through the reduction of the compensation account, currently intended for highly complex care coverage, in 70% of the Fund's total Budget at 15%, and create a new subaccount in order to focus the budget on the primary levels of care for the direct payment of services at levels of care I and II (including emergencies). Subsequently, the fund must be applied to a universal income provided by the State to finance the consultation, procedures and medicines of the first and second level of care.

References

- Macinko James, Hernán Montenegro, Carme Nebot Adell, Carissa F Etienne. “La Renovación de La Atención Primaria de Salud En Las Américas.” Rev Panam Salud Publica, 2007; 21(2/3).

- Andersen RM. et al. Exploring Dimensions of Access to Medical Care. Health Services Research, 1983; 18(1): 49-74.

- Allin Sara, et al. Measuring Inequalities in Access to Health Care: A Review of the Indices? 2007.

- Andersen, Ronald, and John F Newman. Societal and Individual Determinants of Medical Care Utilization in the United States. The Milbank Quarterly, 2005; 83(4).

- Armada F, Muntaner C, Navarro V. Health and Social Security Reforms in Latin America: The Convergence of the World Health Organization, the World Bank, and Transnational Corporations. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation, 2001; 31(4): 729-768.

- Aday Lu Ann, Ronald Andersen. A Framework for the Study of Access to Medical Care. Health Services Research, 1974; 9(3): 208-220.

- Penchansky R, Thomas JW. The Concept of Access: Definition and Relationship to Consumer Satisfaction». Medical Care, 1981; 19(2): 127-140.

- Babitsch, Birgit, Daniela Gohl, Thomas von Lengerke. Re-Revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: A Systematic Review of Studies from 1998-2011». Psycho-Social Medicine, 2012; 9: Doc11.

- Gunnar Almgren MSW. Health Care Politics, Policy and Services: A Social Justice Analysis, Second Edition. 2nd Edition. New York: Springer Publishing Company, 2012.

- Olsen, Jan Abel. Concepts of Equity and Fairness in Health and Health Care. The Oxford Handbook of Health Economics, 2011.

- Health at a Glance: Asia/Pacific 2014: Measuring Progress towards Universal Health Coverage, 2014.

- Toth F. Classification of Healthcare Systems: Can We Go Further? Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 2016; 120(5): 535-543.

- Ayala-García, Jhorland. La salud en Colombia: más cobertura pero menos acceso. Bogotá, Colombia: Banco de la República, 2014.

- Guerrero Torres, Harry Salomón, y Nini Johanna Trujillo Otero. Inequidades en el acceso al sistema general de seguridad social en salud en Colombia, 2013.

- Olavarría Gambi, Mauricio. Acceso a la Salud En Chile». Acta bioethica, 2005; 11(1): 47-64.

- Cabieses, Baltica, Helena Tunstall, Kate E Pickett, and Jasmine Gideon. Understanding differences in access and use of healthcare between international immigrants to Chile and the Chilean-born: a repeated cross-sectional population-based study in Chile. International Journal for Equity in Health, 2012; 11: 68.

- Aguirre-Boza, Francisca, Bernardita Achondo. Towards universal access to health care: incorporation of advanced practice nurses in primary care. Revista Medica De Chile, 2016; 144(10): 1319-1321.

- Wenzl Mossialos. “International Profiles of Health Care Systems, Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, England, France, Germany, India, Israel, Italy, Japan, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United States.” 2015; 180.

- Marshall Martin. “A Precious Jewel--the Role of General Practice in the English NHS.” The New England Journal of Medicine, 2015; 372(10): 893–897.

- Gurch Randhawa, Krishna Regmi. Access to Healthcare: Issues of Measure and Method». Primary Health Care: Open Access, 2013; 03(02).

- Sánchez-Sagrado T. “La atención primaria en el Reino Unido.” SEMERGEN - Medicina de Familia, 2016; 42(2): 110–113.

- NHS England: Improving Access for All: Reducing Inequalities in Access to General Practice Services, 2020.

- Steffen, Monika. Universalism, Responsiveness, Sustainability--Regulating the French Health Care System. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2016; 374(5): 401-405.

- Chambaud Laurent. How Healthy Is the French Health System? The Conversation, 2020.

- Buxeraud Jacques, Sébastien Faure. La carte Vitale. Actualités Pharmaceutiques, 2019; 58(587, Supplement): 31-32.

- Dietrich Cf, Riemer-Hommel P. Challenges for the German Health Care System. Zeitschrift fur Gastroenterologie, 2012; 50(6): 557-572.

- Squires, David Squires, Chloe Anderson Anderson. U.S. Health Care from a Global Perspective: Spending, Use of Services, Prices, and Health in 13 Countries. New York, NY United States: Commonwealth Fund, 2015.

- Access and Disparities in Access to Health Care | Agency for Health Research and Quality, 2020.

- Cohen Robin A, Michael E Martinez. “Health Insurance Coverage: Early Release of Estimates from the National Health Interview Survey, 2015.

- Davis Karen, Melinda Abrams, Kristof Stremikis. How the Affordable Care Act Will Strengthen the Nation’s Primary Care Foundation. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 2011; 26(10): 1201-1203.

- Access to Health Services | Healthy People 2020.

- Haseltine, William A. Affordable Excellence: The Singapore Healthcare Story. Washington, D.C: Brookings Institution Press, 2013.

- Wong CY (1), HC (2) Lee. “Healthcare in Singapore: Challenges and Management.” Japan Medical Association Journal, 2008; 51(5): 343–346.

- Montenegro Torres Fernando, Bernal Acevedo Oscar. Colombia - Régimen subsidiado del sistema general de seguridad social en salud de Colombia - Serie de estudios ÚNICO. UNICO Studies Series; No. 15. World Bank, Washington, DC. © World Bank, 2013. License: CC BY 3.0 IGO.”

- National Healthcare Quality and Disparities Report and 5th Anniversary Update on the National Quality Strategy, 2015.

- Health at a Glance 2017: OECD Indicators, 2017.