Telehealth and COVID-19 pandemic reshape cardiology? In INDIA. Why and how? Telehealth and COVID-19 in INDIA

Rama Kumari N*

Department of Cardiology, Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences, India

Received Date: 21/09/2020; Published Date: 22/10/2020

*Corresponding author: Rama Kumari N, MD,DM: (Cardiology). Presently working as Additional Professor of Cardiology, Dept. of Cardiology, Nizam’s Institute of Medical Sciences, Panjagutta Hyderabad – 500082. Phone: 91-40-23489000, Fax: 91-40-23310076, Email: testinet@yahoo.co.in; testinet15@gmail.com, Mobile: 91 94401 02729, 91 98666 75067

Introduction

The emergence of the novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) began a series of unparalleled changes in healthcare systems worldwide. The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has led to disruption in every aspect of cardiovascular care delivery. After the initial wave of COVID-19 infection subsides, subsequent surge(s) of acute cardiovascular disease (CVD) presentations are expected due to the "double hit" from suspended clinic visits/elective procedures and delays in seeking timely care from patients' fears and misconceptions of quarantine orders [1]. The adverse impact on cardiovascular care delivery and outcomes will likely be long-lasting if our health systems do not adapt quickly and efficiently. In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, a tremendous opportunity arises for implementation and development of primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention via telehealth platforms. Telehealth encompasses, but is not limited to, real-time consultation using audio/video communication technology instead of in-person visits, as well as mobile health and tele monitoring. Medical services in CVD prevention are particularly well suited for transitioning to telehealth platforms as interventions are cantered largely on counselling and are most effective with regular check-in (in-person or virtual) to reinforce good prevention practices. The timely delivery of CVD prevention services, which may be implemented virtually, can help modify risk factors associated with increased morbidity and mortality in patients infected with COVID-19. Moreover, CVD prevention can help alleviate pressure on hospitals by reducing acute presentation of CVD among non-COVID-19 individuals. When we reach the “end” of the COVID era, how will our lives have been changed as practicing cardiologists, Fellows –In- Training (FIT), and human beings in society at large?

The Practice of Cardiology

Disease burden:

Another major focus for providers will be long-term risk reduction of CVD. Prior studies among patients with hypertension and diabetes have demonstrated that self-monitoring, when coupled with counselling/tele-counselling, web/phone-based feedback and education resulted in clinically significant improvement of blood pressure, haemoglobin A1c, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) [2-3]. In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, when routine clinic visits are often delayed or cancelled, the impact of telehealth interventions for risk factor modification may be even greater. Barriers for patients to utilize telehealth may include limited resources or limited health literacy and for the geriatric population, facility with electronic communication platforms as well as impaired vision or hearing, which can make virtual communication difficult. Special considerations must be taken to address delivery of care in these at-risk populations.

From an in-patient perspective, we are witnessing multi organ damage from COVID-19, including thrombotic sequelae, marked kidney injury, and cardiac arrhythmias. As cardiologists, we should expect an influx of outpatients who suffered cardiac complications from COVID or for whom hospitalization unmasked conditions of hypertension, diabetes, coronary artery disease, or cardiomyopathy [4].

Globally, there has been a marked decline in non-COVID medical disease presenting to hospitals, such as Myocardial Infarctions (MI) [5]. Theories abound on whether the decrease in MI represents an actual reduction with at-risk individuals abstaining from triggers or whether patients are avoiding the health care system and infracting at home. In COVID patients, electrocardiographic abnormalities consistent with acute MI do not always represent obstructive coronary disease [6]. As true ST-segment elevation MI volumes resurge, discussions favouring fibrinolysis, recently resurrected to reduce personnel exposure and due to delays in door-to-balloon time, should diminish, to re-emphasize primary percutaneous coronary intervention as the standard of care [7].

Financial burden:

Hospital systems and private practices have suffered considerable financial losses in prioritizing care for patients with COVID-19 coupled with a precipitous decline in elective procedures.

Tele-health in developing countries:

One of the silver linings of this human crisis has been cardiology engagement with 21st century technology. Even though the opportunity to perform video visits has been present for over a decade it has taken a pandemic for telemedicine to be nationally accepted.

In the setting of the COVID-19 pandemic, when routine clinic visits are often delayed or cancelled, the impact of telehealth interventions for risk factor modification may be even greater. Barriers for patients to utilize telehealth may include limited resources or limited health literacy and for the geriatric population, facility with electronic communication platforms as well as impaired vision or hearing, which can make virtual communication difficult in under developed countries. Special considerations must be taken to address delivery of care in these at-risk populations.

Conferences:

National conferences, the broadening of the COVID-19 outbreak resulted in mass cancellations of cardiology meetings that were expected to attract hundreds of thousands of participants. Organizers scrambled to find innovative solutions to absorb the impact of those cancellations, such as the offering of essential components of the meeting on virtual platforms. While the success of this approach is yet to be determined, debates on the relevance of live conferences in the modern era have resurfaced. Arguments were made on the diminishing value of in-person meetings in view of the growth in multisource and online education. However, proponents of live meetings suggest that those serve additional purposes beyond dissemination of medical knowledge including the offering of a platform for networking, hands-on training, and cross-discipline learning. The impact of COVID-19 on future cardiology meetings is difficult to predict, but it is likely that the majority of those meetings will include a mature ‘virtual’ option that may attract an increasing audience, and perhaps one that is more diverse given the challenges of travel for physicians with young families, caregiving responsibilities for elderly parents, physicians with disabilities, or colleagues with limited funding.

Fellows-in-training:

In the past months, FITs have learned skills in critical care, virology, and palliative medicine as frontline providers. Yet, we must remain committed to core cardiology education. Despite the Accreditation

Council for Graduate Medical Education’s way to cancel conferences in pandemic emergency status, we have resisted this, deciding that maintaining education provides stability in disruptive times. Video conferencing has been a success, with widespread participation of fellows and faculty. Whereas live lectures will gradually return, video conferencing will persist in parallel with improved HIPAA (Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996)-compliant platforms and inter institutional sharing. Virtual education is being embraced at international levels. There were over 38,000 attendees representing more than 135 countries at the virtual American College of Cardiology/World Congress of Cardiology Scientific Sessions this year, validating the concept that online learning is far-reaching and inclusive for trainees who may not be able to participate due to financial or logistical reasons. Loss of rotations and cases has also imperilled fellows in many programs to fall short of procedural requirements. For some, this will mean extension of training pathways, but it will also force educators to reconsider how we teach. Simulation training platforms can provide virtual repetition and pattern recognition for procedures such as transthoracic or trans-oephageal echocardiography, vascular access, and even structural heart interventions. The distinction between procedural competency and procedure.

Community-based impact:

With many in self isolation, the community-based impact of COVID-19 on cardiovascular health will be important to monitor. Exercise programs via online platforms have become pervasive, but will they be enough to counter inactivity while at home? The COVID-19 pandemic will leave a profound imprint on cardiologists, trainees, and society for years to come (Figure 1) [8]. We will have supported each other to the best of our ability, understanding that the mental health sequelae for health care professionals will be important to address. As with in-person counselling, lifestyle counselling regarding diet, physical activity, and weight loss can also be readily performed on telehealth platforms. Such interventions should be specific and personalized, accounting for potential socioeconomic barriers or physical limitations. Telehealth may enhance understanding of socioeconomic barriers to care by allowing the provider a glimpse directly into the patient's home. Another area of importance that can be addressed by telehealth is medication refill and adherence. Routine clinic visits afford clinicians the opportunity to evaluate and reinforce medication adherence, make necessary adjustments, and refill medications. When implementing telemedicine, providers must familiarize themselves with the liability, licensure, billing and documentation requirements as pertaining to their individual practice. To facilitate workflow, providers may consider setting aside a block of time for scheduled tele-visits and co-ordinate with patients prior to the visit to ensure availability and ascertain familiarity with the communication platform.

Conclusion

Telehealth has provided clinicians a temporary recourse to continue delivering high-quality medical care to patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. For CVD prevention, however, the amplified interest in telehealth among providers and expansion in coverage by insurance has aligned to create a rare opportunity to improve care delivery. Clinicians, health systems and public policy makers should continue to build upon this momentum to incorporate telehealth care delivery into CVD prevention practices in long-term.

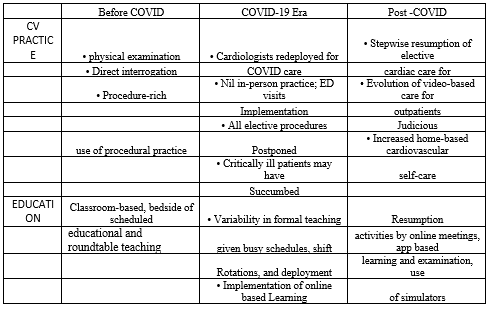

Cardiovascular Practice, Education, and Environment

Figure 1: The coronavirus disease (COVID) 2019 pandemic has resulted in significant changes for cardiology practice and trainee education, cv ¼ cardiovascular E.D, 1/4, Emergency department.

Conflict of Interest

None

Ethical Committee Approval

Not necessary

References:

- Bhatt AS, Moscone A, McElrath EE, et al. Declines in hospitalizations for acute cardiovascular conditions during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicentre tertiary care experience.J Am Coll Cardiol 2020;76:280-288.

- Tucker KL, Sheppard JP, Stevens R, et al. Self-monitoring of blood pressure in hypertension: a systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis. PLoS Med2017;14: e1002389

- Shea S, Weinstock RS, Teresi JA, et al. A randomized trial comparing telemedicine case management with usual care in older, ethnically diverse, medically underserved patients with diabetes mellitus: 5 year results of the IDEATel study. J Am Med Inform Assoc2009;16: 446-456.

- Guo T, Fan Y, Chen M, et al. Cardiovascular implications of fatal outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). JAMA Cardiol.2020 Mar 27 [E-pub ahead of print].

- NYC Health. Confirmed and Probably COVID-19Deaths Daily Report. April 14, 2020. Available at ttattps://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/imm/covid-19-deaths-confirmed-probabledaily-04152020.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2020.

- Bangalore S, Sharma A, Slotwiner A, et al. STsegment elevation in patients with COVID-19: acase series. N Engl J Med 2020 Apr 17 [E-pub ahead of print].

- Mahmud E, Dauerman HL, Welt FG, et al.Management of acute myocardial infarction duringthe COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Coll Cardiol 2020Apr 21 [E-pub ahead of print].

- Nupoor Narula, MD, Harsimran S. Singh, MD, MSC, journal of the American college of cardiology, 76(4): 2020.