Ageism and Lack of Shared Decision-Making is a Problem in Healthcare and Geriatrics

Georg Bollig1,2,*

1Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care, Palliative Medicine and Pain Therapy, Helios Klinikum Schleswig, Germany

2Department of Palliative Medicine, Faculty of Medicine and University Hospital, University of Cologne, Kerpener Strasse 62, 50937 Cologne, Germany

Received Date: 26/10/2023; Published Date: 05/04/2024

*Corresponding author: Dr. Georg Bollig, PhD, MAS, Department of Anesthesiology, Intensive Care, Palliative Medicine and Pain Therapy, Helios Klinikum Schleswig, St. Jürgener Str. 1-3, 24847 Schleswig, Germany

Keywords: Geriatrics; Geriatric medicine; Ethics; Shared decision-making

Introduction and Background

Most people want to make their own decisions about their life in general and of course also about their medical treatment and end-of-life care. Many elderly people prefer shared decision-making and the participation of their relatives when important decisions about their health and medical treatment options have to be made [1]. In contrast many elderlies unfortunately experience that they are not included in decision-making [2]. Many elderly people experience a lack of participation in decision-making concerning their daily life and medical treatment. This can for example lead to both everyday ethical challenges and to ethical challenges connected to medical treatment and end-of-life decisions [2]. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) “one in two people are ageist against older people” [3]. The WHO states that “age is often used to categorize and divide people in ways that lead to harm, disadvantage and injustice and erode solidarity across generations [3]. Ageism is usually defined as discrimination, stereotypes and prejudice of people based on age and affects often elderly and old people [3]. Ageism is a threat to older people’s well-being and needs to be addressed in the whole society and in healthcare [4]. Ageism should always be kept in mind and avoided in healthcare and especially in geriatrics.

Case Report

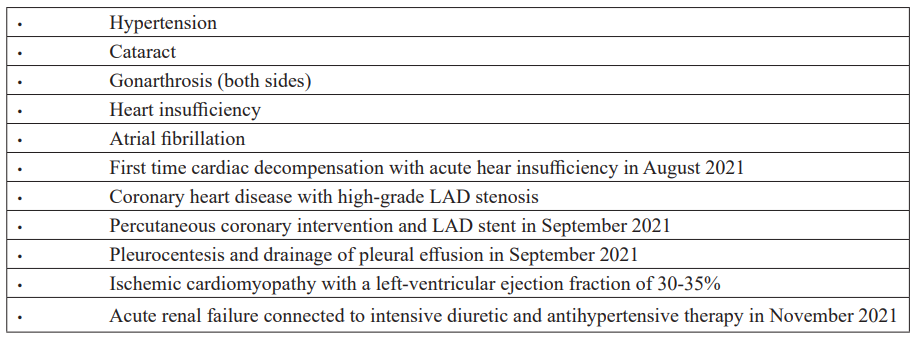

The following case study describes a series of hospital admissions and the treatment of an 88-year-old woman who was previously healthy and independent all her life despite of a past medical history of hypertension, gonarthrosis and cataract. Her husband had died nine months before her first hospital admission in August 2021 after she had cared for him for more many years in their own home. A list of the diagnoses that were found during the series of hospital admissions starting in August 2021 is shown in Table 1.

First Hospital admission August 2021: In August 2021 an 88-year-old previously healthy female patient was admitted to a medical department of a local hospital because of dyspnoea, high blood pressure, heart insufficiency and acute decline of her general condition on a Friday directly after a visit to a specialist in cardiology. The patient had been sent to the cardiologist by her general practitioner because of dyspnoea und oedema of both legs. After arrival in the hospital a chest x-ray was taken, and pleural effusion diagnosed. The patient received therapy with diuretics and medication for her high blood pressure during the hospital stay. She was discharged on Monday directly after the weekend without any further investigation what the cause of her acute heart insufficiency could have been. The patient and the relatives did not get relevant information about the cause of the disease or its further treatment. The patient was sent back home with the recommendation to be treated further by her general practitioner.

Second hospital admission September 2021: A few weeks after the initial admission with her first-time acute heart insufficiency the patient had to be readmitted to the hospital due to dyspnoea and high blood pressure. More extensive diagnostics were only started because of the patients and the families demand to find the cause of the underlying disease with new and severe symptoms over the last weeks. Until August 2021 the 88-year-old lady had led an independent life without dyspnoea. She had been able to care for herself and to prepare her meals on her own without any help. The patient’s ejection fraction was found to be 33-35% and she had again pleural effusion. During the hospital stay a coronary angiography was performed and a stent inserted in the left main coronary arteria (LAD). The patient was set on medication with anticoagulants, a beta-blocker, and intensive diuretic treatment with sacubitiril/valsartan, torasemide and spironolactone.

After discharge from the hospital in the end of September the patient felt very weak, had still mild oedema of the legs, felt often dizzy and had to get up several times every night to go to the bathroom. Her son took the patient to his family home in a town far away from the patients’ home to visit them and to support the patient during her recovery after the hospital admissions.

Third hospital admission November 2021: During the stay at her sons home the patient became acutely ill again with declining general condition and confusion. She was admitted to the local regional hospital due to a suspected infection and trouble with urinating. In the hospital a life-threatening condition with pneumonia, urinary tract infection and acute kidney failure was diagnosed and treated. The intensive medical treatment of the patient’s heart insufficiency was suspected to be a cause of the acute renal failure. Within the next week the patient recovered in part and a decision was made to transfer the patient to a geriatric department for geriatric rehabilitation.

Transfer to geriatric rehabilitation (in-hospital) November 2021: The patient’s recovery was very slow and complicated by a gastrointestinal bleeding with the need for blood transfusion. A gastroscopy revealed a bleeding in the duodenum and a treatment with high dose pantoprazole was started. In addition, a radiotherapy for her painful gonarthrosis was performed. Geriatric testing included different tests including a Mini Mental State examination (MMSE) of 25/30 and mild impaired mobility and ability to care for herself. Although the patient and her son asked to extend the in-hospital geriatric rehabilitation the patient was discharged after 3 weeks (which is the usual length of a geriatric in-hospital rehabilitation). They were informed that an extension of the in-hospital treatment was not possible despite of the complicated medical condition with acute renal failure, heart insufficiency and gastrointestinal bleeding.

Geriatric outpatient treatment December 2021: As there was no option to extend the in-hospital geriatric rehabilitation the patient was discharged to a short-term place in a nursing-home in combination with a geriatric outpatient treatment in a geriatric day-care facility connected to the geriatric department. Unfortunately, the training with physiotherapists and other therapies were not as frequent as during the in-hospital geriatric treatment. That hampered the further rehabilitation of the patient. During this period the patients heart insufficiency and general condition got worse again and the patient should be admitted again to treatment in the in-hospital geriatric department.

Fourth hospital admission in December 2021: As the trust in the geriatric team was disturbed by the early discharge and lack of appropriate rehabilitation in the geriatric out-patient department the patient and her son preferred an admission to the cardiology ward of another hospital where the patient had been before. During this hospital treatment the patients heart insufficiency and chronic diminished renal function could be stabilized. The patients condition became better with less dyspnoea and less pleural effusion and a better overall physical function and ADL. The diuretic and antihypertensive therapy was reduced and less aggressive than before the hospital admission in November 2021.

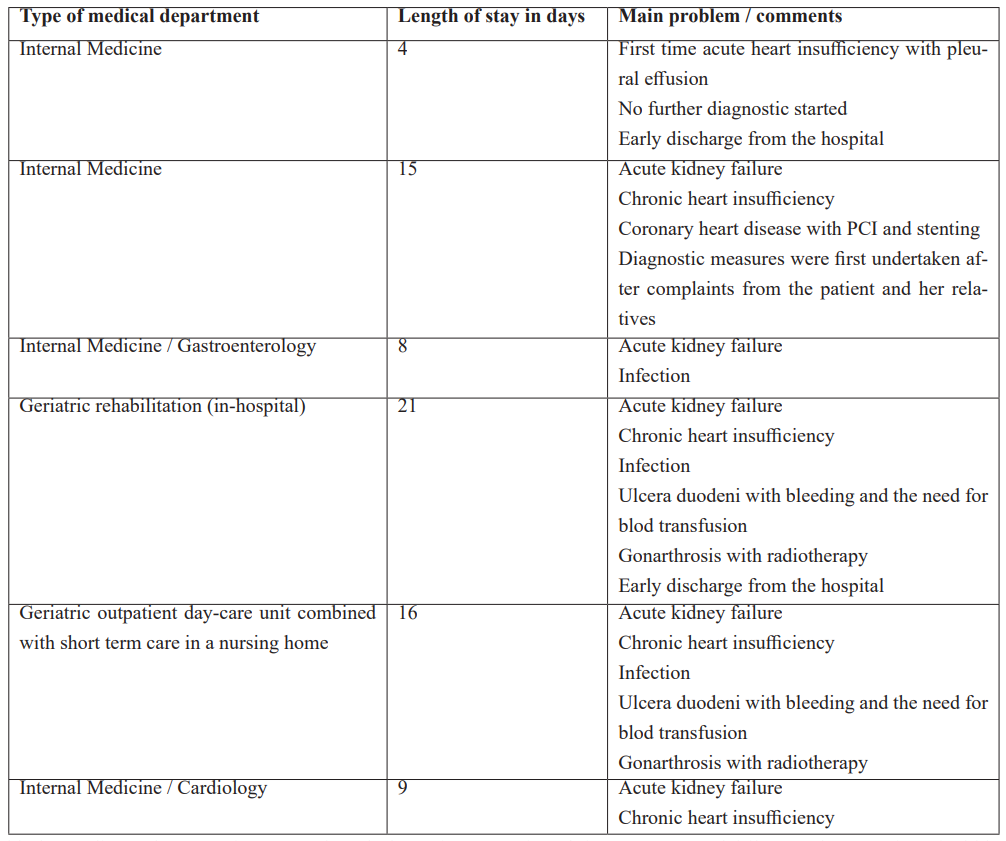

Table 2 provides an overview over the patient’s hospital admissions, length of hospital treatment, main problems and comments.

After discharge from the department of cardiology in January 2022 the patients lived a short period in the short-term ward of a nursing-home before she returned home by ambulance.

Back home again January 2022: After coming home again the patient received care by her general practitioner and a mobile nurse attending once or twice ca day. In the course of the next months the patient regained her ability to care for herself and got nurse visits only once a day.

Long-term outcome and status in October 2023: One and a half years later the patient is still living in her flat with minimal help from a mobile nurse visiting her once a day. Taking her age and her medical history into account the patients’ health is at present quite stable and she has a very good self-reported quality of life. She has been a professional tailor before and is now able fill her day with tailoring cloth, learning languages (Spanish and English) and loves to listen to classical music. She enjoys visits of her children and grandchildren. To be prepared for the future she has gone through her advance care planning and has assigned two of her four children as surrogate decision-makers. So far, she still continues to make her own decisions but still prefers shared decision-making with inclusion of her family.

Reflections on the treatment course: During the series of hospital admissions, the patient and her family experienced ageism in a number of situations. During the first admission the patient did not receive appropriate diagnostic and treatment for the underlying condition. Diagnostic and therapy of her severe coronary stenosis was first performed after pressure from the family. Often the patient was not included or addressed in talking with the physician in the hospitals. Most physicians turned to the relatives when talking about decision-making although the patient was participating in the meetings. The patients wish to be hospitalized and treated until her rehabilitation would enable her to live at home again was neglected. the patients and relatives’ impression were that the patients aim to be rehabilitated to be able to live on her own in her flat was not seen as possible or achievable with the existing option with an in-hospital rehabilitation period of only three weeks and without taking the existing complications into account. Both patient and the relatives felt that she was discharged as soon as possible without respecting her aims and wishes for the treatment and wishes for her future living situation. Instead of helping the patient to reach her aim to be able to move back into her own home the advice of most physicians was to seek a place in a long-term care facility. That was strictly against the patients’ preferences. The present case study shows that this rehabilitation in accordance with the patient’s wishes and preferences was possible. Unfortunately, the course of her rehabilitation was hampered due to early discharges from hospitals both after medical treatment and geriatric rehabilitation.

Table 1: List of diagnoses of the patient.

Table 2: Hospital admissions of the patient in 2021.

Discussion and Conclusion

The above shown case study illustrates that ageism is existing not only in health care in general but also in geriatrics. Although a geriatric department should take care of old patients and try to find the best suited treatment and solution for the patients according to their wishes and preferences the presented case highlights that the patient was discharged too early during a possible rehabilitation to a short-term ward in a nearby nursing home. Although the patient had different diseases as heart insufficiency, acute renal failure, and a gastrointestinal bleeding during her treatment in the geriatric department the stay was not extended and in contrast to the wishes of the patient and her relatives who had asked to prolong the stay to enable the patient to move home again. Instead, she was transferred to a nursing home with additional treatment in a day-care unit of the geriatric department. The patient had to live in a nursing-home with daily transport to the geriatric day care instead of a longer stay in the geriatric department of the same hospital. During this period with daily care in the geriatric day care her health condition declined again.

This led to a hospital readmission which might have been preventable by a longer stay during the previous admission. As shown by Gupta et al. may a discharge to a post-acute care facility indicate a worse prognosis [5]. Furthermore, readmission after discharge is the primary risk factor for additional readmissions and death [6]. Kerminen et al. recommend that the patient's functional ability, activities of daily living (ADL) need, and mobility problems should be addressed before discharging a patient [7]. In the described case study, the patient was still in an ongoing rehabilitation phase working to regain her pre-illness activities of daily live ADL-level and mobility. This illustrates that it might be better to discharge a geriatric patient first when the patient is as stable as possible, and the treatment is definitively finished. From an ethical point of view the patient’s autonomy must be respected and his wishes and preferences must be heard and addressed [8]. Shared-decision making should be a standard when caring for geriatric patients [1,2,8]. In contrast to that the patient in the current case study and her family felt that their opinion and wishes were not listened to during the hospital stay in the geriatric department. Therefore, the patient and her family decided to be transferred to a medical department of another hospital instead of readmission to the geriatric ward. This underlines that trust is an important part of the physician-patient-relative relationship and shared decision-making. During the last hospital admission in the cardiology department the patient decided to be discharged to her home by ambulance. She decided that she rather wanted to die at home than to continue the hospital treatment. After her return home in January 2022, she has not been admitted to hospital again and lives since with a very good quality of life. She has help from a nurse only once a day and regular follow up by her general practitioner and a cardiologist. In summary the presented case study has shown some important aspects of ageism and lack of shared decision-making in healthcare. These include:

- Ageism as barrier for optimal diagnostics and treatment

- Lacking respect for patient autonomy and shared decision-making

- Too early discharge as problem for elderly patients

The associations for palliative geriatrics in Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Luxemburg have stated in a current policy paper that the aims for treatment and living of elderly and old people have to be discussed with them and that their wishes must be respected [8]. Therefore, it is paramount to discuss these aims including the patient and relatives’ viewpoints and wishes and to engage in shared decision-making. This may contribute to ensure that the patient’s wishes will be better respected in the future and might also help to reduce ageism.

Competing interest: None

Patient consent: The patient has given informed consent to the publication of her case. By publishing her case she wants to contribute to the awareness of ageism in healthcare including geriatrics for the elderly and old people.

References

- Bollig G, Gjengedal E, Rosland JH. They know! - Do they? A qualitative study of residents and relatives views on advance care planning, end-of-life care, and decision-making in nursing homes. Palliative Medicine, 2016; 30(5): 456-470.

- Bollig G, Gjengedal E, Rosland JH. Nothing to complain about? – Residents’ and relatives’ views on a “good life” and ethical challenges in nursing homes. Nursing Ethics, 2016; 23(2): 142-153.

- World Health Organization (WHO), 2023.

- Marques S, Mariano J, Mendonca J, et al. Determinants of Ageism against Older Adults: A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, 2020; 17(7): 2560.

- Gupta S, Perry JA, Kozar R. Transitions of Care in Geriatric Medicine. Clin Geriatr Med, 2019; 35(1): 45-52.

- Visade F, Babykina G, Puisieux F, et al. Risk Factors for Hospital Readmission and Death After Discharge of Older Adults from Acute Geriatric Units: Taking the Rank of Admission into Account. Clin Interv Aging, 2021; 16: 1931–1941.

- Kerminen HM, Jäntti PO, Valvanna JNA, et al. Risk factors of readmission after geriatric hospital care: An interRAI-based cohort study in Finland. Arch Gerontol Geriatr, 2021; 94: 104350.

- Fachgesellschaft Palliative Geriatrie (FGPG). Grundsatzpapier Lebens- und Therapiezielfindung, 2023.