Personality Traits Among Burnout Patients: Differences Between Psychiatric Burnout Patients and Controls with Regard to the Big 5 Personality Traits

Ulrike Kipman1,*, Sandra Eibl2, Stephan Bartholdy3, Marie Weiß4, Günter Schiepek5, Wolfgang Aichhorn6

1Institute of Educational Sciences and Research, College of Education, Austria

2University of Klagenfurt, Austria

3University of Salzburg, Austria

4University of Graz, Austria

5Institute of Synergetics and Psychotherapy Research of Paracelsus Medical Private University, Austria

6Paracelsus Medical Private University, Austria

Received Date: 20/09/2021; Published Date: 15/10/2021

*Corresponding author: Ulrike Kipman, Institute of Educational Sciences and Research, College of Education, Austria

Abstract

Burnout describes a process, that takes years and is accompanied by symptoms like unmanaged stress, emotional exhaustion and reduced performance. Research in connection with personality traits found that extraverted, agreeable, open, conscientious and emotionally stable individuals have a lower risk of burnout and that these traits can predict part of the risk of burnout, as well as avoidance tendencies, such as openness towards problem solving and distancing ability. To investigate these factors, data from 126 diagnosed burnout patients and a set of 402 working adults was analyzed. We used single and multiple linear regression models as well as analyses of variance to compare these two groups. The personality dimensions of the participants were measured with the BFI-10 and the avoidance tendencies with two subscales of the AVEM. Our findings show that burnout patients exhibit a higher score in neuroticism and a lower score in extraversion than the control group. Neuroticism has a significant negative relationship with burnout risk, whereas extraversion has a significant positive relationship with burnout risk. Furthermore, distancing ability and openness to towards problem solving have a positive direct and mediating impact on the risk of developing burnout. With the help of these findings one can evolve new action-oriented and adaptive strategies for patients with burnout or people who are at risk of getting it.

Introduction

The term burnout gained importance in the 1970s thanks to its founder Herbert Freudenberger. In the meantime, the term burnout has become part of everyday language in a job context (Scheuch & Seibt, 2007) [1] and is "by far one of the most frequently cited psychological concepts of our time." From the beginning, burnout has been perceived as a social problem that occurs primarily in the context of (failed) relationships at work (Maslach, 2003; Maslach et al., 2001) [2,3]. The term burnout itself implies that something happens suddenly. In fact, the process of burnout usually takes years, progressing inconspicuously at first and is accompanied by unmanaged stress, emotional exhaustion and reduced performance (Maslach, 2003; Scheuch & Seibt, 2007) [1,2]. The concept of burnout was essentially coined by Christina Maslach, whose Maslach Burnout Inventory (MBI) has been used for a large number of studies.

She describes burnout as "a prolonged response to chronic emotional and interpersonal stressors on the job and is defined [...] by the three dimensions of exhaustion, cynicism, and the sense of inefficacy." (Maslach, 2003) [2]. Only an interaction of the three components leads to burnout (Scheuch & Seibt, 2007) [1]. Emotional exhaustion is associated with feelings of being overwhelmed and comes at the expense of emotional and physical resources. Depersonalization (or cynicism) is coupled with negative, jaded feelings about work and people. Reduced performance is paired with feelings of incompetence and decreased productivity (Maslach et al., 2001) [3]. According to (Bakker and Costa 2014) [4], burnout is "a combination of chronic exhaustion and negative attitudes towards work with damaging consequences for employee health and productivity." Bakker and Costa (2014) [4] refer to the negative impact of burnout on health in addition to emotional exhaustion and reduced performance.

Burnout is therefore described as a special kind of job distress with emotional depletion, missing motivation and a negative emotional reaction to job, means a high disharmony between job nature and job holder’s nature. It includes emotional exhaustion, depersonalization and diminished personal accomplishment and influences one individual’s attitudes, physical and mental health and behavior. Burnout therefore is described as a syndrome with several associated symptoms, including exhaustion, frustration, and a feeling of failure, which compromises work performance. Its etiology appears multifactorial, involving a demanding workload, diminished work-related control, difficulty balancing personal and professional responsibilities, and coping strategy. Lack of empathy, assertiveness, and emotional intelligence have also been associated with burnout.

In addition, other psychological factors including personality may be important. Personality encompasses an individual’s unique way of interacting with the environment and has been categorized by the Five Factor Model into five dimensions: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

Personality traits shape the perception of and reactions to stress and strain (Lazarus, 1994) [5]. The relationship between personality traits and the risk of burnout has already been well researched. Based on previous findings, it is assumed that extraverted, agreeable, open, conscientious and emotionally stable individuals have a lower risk of burnout (Alarcon et al., 2009; Bakker et al., 2006; Kokkinos, 2007) [6-8] and that personality traits can predict part of the risk of burnout.

In scientific discourse, it is primarily the personality trait neuroticism that is associated with poor stress coping and burnout and is therefore considered a risk factor for burnout (Bakker et al., 2006; Barford & Whelton, 2010; Ghorpade et al., 2011; Käser & Wasch, 2009; Kokkinos, 2007; Manlove, 1993; Weishuber & Thomas, 2015a; Zawadzka et al., 2018) [7-12]. Neurotic individuals react insecurely, anxiously or nervously in stressful situations and their coping with stress is barely adaptive (Rammstedt et al., 2004; Weishuber & Thomas, 2015a) [13]. Bakker et al. (2006) [7] summarize that people who have high scores in the dimension of neuroticism and who also use ineffective coping strategies are particularly susceptible to burnout in stressful situations. Research by Alarcon, (Eschleman et al.,2009) [6] and (Barford et al., 2010) [9] shows that emotional stability, the antithesis of neuroticism, predicts lower emotional exhaustion and reduced depersonalization. In addition to neuroticism, the personality trait extraversion is often discussed in the context of burnout. Empirical studies suggest that extraversion is associated with higher performance and lower depersonalization and has a protective effect (Bakker et al., 2006; Kokkinos, 2007) [7,8]. Alarcon et al., (2009) [6] were able to demonstrate protective associations of extraversion with each of the three burnout dimensions. Negative associations to Maslach's three burnout dimensions were also found for the personality trait conscientiousness (Alarcon et al., 2009; Zawadzka et al., 2018) [6,12]. Kokkinos (2007) [8] found positive correlations between conscientious individuals and depersonalization as well as performance. In this context, individuals with lower conscientiousness showed greater depersonalization, whereas individuals with high conscientiousness reported increased performance. Similarly, tolerant individuals appear to be less at risk of burnout than their less accommodating colleagues (Alarcon et al., 2009; Zawadzka et al., 2018) [6,12]. Openness to experience has also been negatively associated with burnout (Kokkinos, 2007) [8]. For example, Barford and Whelton (2010) [9] summarized that open individuals have the highest scores in personal performance. Even though the results diverge depending on the study or study design, a large part of the results support the assumption that neuroticism increases the risk of burnout, while extraversion, agreeableness, openness to experience and conscientiousness have a positive effect on mental health. In other studies, the ability to distance oneself and the openness towards problematic issues as so-called avoidance processes were associated with burnout or the risk of burnout.

As far as the connection between avoidance tendencies and a potential risk of burnout is concerned, a variety of findings have been established in comparison to the approach tendencies. Considering the fact that certain individuals are frequently exposed to stressful situations that can deeply affect their feelings, the ability to distance oneself from occupational problems seems all the more significant (Gebauer, 2000; Schaarschmidt, 2008) [14]. People who have a high ability to distance themselves can cope better with work-related problems, feel less exhaustion and are less likely to fall ill (Hillert, 2013; Schaarschmidt & Fischer, 2008) [14]. Connections with burnout have also been confirmed for offensive problem solving (Clunies-Ross et al., 2008; Lehr, 2004) [15]. According to this, healthy persons tend to have more offensive problem-solving skills than their ill colleagues (Lehr, 2004). It is therefore expected that the avoidance tendencies of offensive problem solving and ability to distance oneself can predict the risk of burnout, even in cases where personality traits and contextual factors are controlled.

The AVEM method (work-related behaviour and experience pattern; Schaarschmidt & Fischer, 2008) [14] considers offensive problem solving und distancing ability as components of resistance to stress. People at increased risk of burnout are characterised by reduced psychological resistance, which includes poor offensive problem solving (Schaarschmidt & Fischer, 2008) [14]. Problem solving has also been empirically linked to depression. Findings suggest strong empirical associations between good problem coping and low depression along with better health (Heppner et al., 2004; MacNair etal., 1992) [16,17]. The research findings in this area provide empirical evidence that proactive coping behaviour is coupled with lower burnout risk and acts as a protective variable. People with good coping skills were found in studies to have higher levels of perseverance and to view success as a manifestation of their own abilities rather than luck (Heppner et al., 1995; Heppner et al., 1982; Heppner et al., 2004; MacNair & Elliott, 1992) [16-19].

In combination with this, the ability to distance oneself is an interesting feature:

According to Hillert, "The ability versus inability to mentally distance oneself from work, especially after failures," has a significant influence on the risk of burnout (Hillert et al., 2012, p. 28). Another study showed that a lack of distancing ability in sick people is coupled with a tendency to work beyond one's own capacity (Lehr, 2004). However, in comparison to studies concerning the classical personality factors, there are only a few studies that comprehensively examine how the ability to distance oneself and offensive problem-solving affect sensory development at work, which is why these two parameters were co-modelled as mediator and moderator in this study.

The purpose of the study is to investigate the influence of certain personality traits on the risk of burnout and to examine action processes, such as the ability to distance oneself from work and offensive problem solving, for their possible moderating or direct influence on the risk of developing burnout. As already mentioned, these processes are closely connected to work performance, coping mechanisms, stress management, stress resistance and subsequently to burnout. It can therefore be assumed that, in addition to a connection between certain personality traits and an increased risk of burnout, the study also shows an influence of avoidance processes on this risk. If this is the case it would be particularly interesting for the handling and treatment of burnout, since changes in these avoidance tendencies would be much easier to bring about than changes in personality. Because for a change in action you just need to modify approaches of work-related problems and stress with the help of different strategies and coordinated practice. In comparison, a change in personality is much more difficult, due to the fact that personality traits are very stable and constant over time. So, this study should show ways for helping people with burnout by providing knowledge about certain action processes and their impact on this syndrome. It could lead the way to develop new strategies for prevention and improvement of burnout and its accompanying symptoms.

The mentioned personality traits and the two moderators/mediators (offensive problem solving and distancing ability) selected are described below:

Openness to experience

Openness to experience is a personality trait that describes a creative individual, intellectually curious, with an active imagination, adventurous, with unconventional ideas. Individuals that have this personality trait are unpredictable, risk takers, they lack concentration and appreciate the importance of spiritual and artistic quests [7, 8, 9]. This personality trait is directly related to a successful academic performance in students as well as a successful workplace performance [1, 10].

This personality trait describes the level of self-competence, work discipline, organization and scheduling, self-control, the acceptance of conventional rules and the responsibility towards others [1, 7, 14]. Individuals that have this personality trait are organized, reliable, self-disciplined, act with dignity, are attentive and persistent [15].

Extraversion

Individuals with this personality trait are friendly, warm, social, extroverted, energetic, ambitious, confident and seek enthusiasm and stimulation through communication and conversation with others.

Agreeableness

Agreeableness is a dimension that involves someone’s behaviour towards others. Individuals with this personality trait are trustful, altruistic, cooperative and modest. They demonstrate sympathy and concern for the needs of others. They also show understanding in order to avoid conflict. Individuals that are not agreeable may be described as selfish, suspicious and unscrupulous [15, 7].

Neuroticism

This personality trait describes an individual’s tendency to be under psychological stress [9]. Individuals with this personality trait are sensitive and usually face negative feelings such as anger, stress and depression [7]. Neuroticism is related to the degree of emotional stability. Emotionally stable individuals are described as calm, stable, mature and resilient. Individuals with low emotional stability are irritable. Low emotional stability can be observed in insecure individuals as well as dynamic individuals, since in many cases it incurs from their dynamism [1, 15].

Distancing ability

Distancing ability is considered an active effort by the person in the dual process model (Wong, 2012) and is the "ability to mentally recover from work" (Schaarschmidt & Fischer, 2008) [14] or also "the ability to distance oneself from contextual and social demands in professional life" (Viernickel et al., 2014). Instead of using leisure time for recreation, people with a low ability to dissociate also engaged mentally or physically with work after it was over.

Offensive problem solving

Offensive problem solving is described as an "active and optimistic attitude towards challenges and problems that arise" (Schaarschmidt & Fischer, 2008) [14] and is necessary for an active transformation of problematic situations. It can be assumed that every person can actively change the patterns of their own thinking, acting and evaluating (Wong, 2012). Therefore, offensive problem-solving is closely linked to confidence in one's own abilities, an optimistic attitude towards life, problem-solving ability and proactive action (Schaarschmidt & Fischer, 2008) [14]. Good problem-solving skills include the ability to name and systematically address problems rather than to avoid them (MacNair & Elliott, 1992) [17].

Methods

The purpose of this study is to determine relationship between burnout risk and personality traits as well as finding differences between burnout patients and controls with regard to personality traits as well as for openness for problem solving and for the ability to distance oneself from the expectations of others (distancing ability).

Participants

We analyzed data from 126 diagnosed burnout patients, getting an inpatient treatment in a clinic of psychosomatic or getting an outpatient treatment by a psychologist and a set of 402 working adults, using single and multiple linear regression models as well as analyses of variance to compare these two groups.

Procedure

For all statistical analyses, SPSS version 26.0 (2020) was used. To analyze the impact of personality traits on burnout risk with regard to avoidance tendencies, such as the ability to distance oneself and openness towards problem solving, simple linear and multiple regression models as well as mediation analyses (SPSS26.0, PROCESS v35) were conducted, while differences between burnout patients and controls were analyzed using z-statistics (SPSS).

Instruments

Personality Traits

The short scale for measuring the Big Five personality dimensions (BFI-10; Rammstedt, Kemper, Klein, Beierlein & Kovaleva, 2012) [12] was used to record the personality traits. These items were also answered using a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true, 5 = completely true). An example item is: "I am rather shy and reserved." The entire scale was taken from the original.

Avoidance Tendencies - Distancing Ability and Offensive Problem Solving

The two avoidance tendencies were measured with two subscales of the multidimensional personality diagnostic procedure Work-Related Behaviour and Experience Pattern (AVEM; Schaarschmidt & Fischer, 2008). An example item to assess offensive problem solving is: "When I don't succeed in something, I persist and try all the harder." An example to assess distancing ability is: "Even in my free time, I am concerned about many work-related problems." The items were answered on a five-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true, 5 = completely true). The reliability of the distancing ability scale in the present questionnaire is α = .85.

Results

In single regression analyses (Table 1,2) we found a significant positive impact of extraversion on burnout-risk (β= -.174, p= .000) and a significant and practically relevant negative impact of neuroticism on burnout risk (β= .418, p= .000). Furthermore, results show a tendency for agreeableness (β= -.072, p= .098). High neuroticism and low extraversion as well as low agreeableness therefore increase the risk of burnout.

Table 1: Single regression models for personality traits.

Regarding avoidance tendencies such as openness and the ability to distance oneself from the expectations of other, we found an even greater impact, namely a significant and practically relevant positive impact of the ability to distance oneself from the expectations of other (distancing ability) on burnout-risk (β= -.410, p= .000) and a significant positive and practically relevant impact of openness towards problem solving on burnout risk (β= -.238, p= .000).

Table 2: Single regression models for avoidance tendencies.

Combining all significant predictors in one model (R2= 27.2%), the two avoidance tendencies as well as neuroticism stayed significant predictors, extraversion was no longer a significant predictor (Table 3):

Table 3: Combined model.

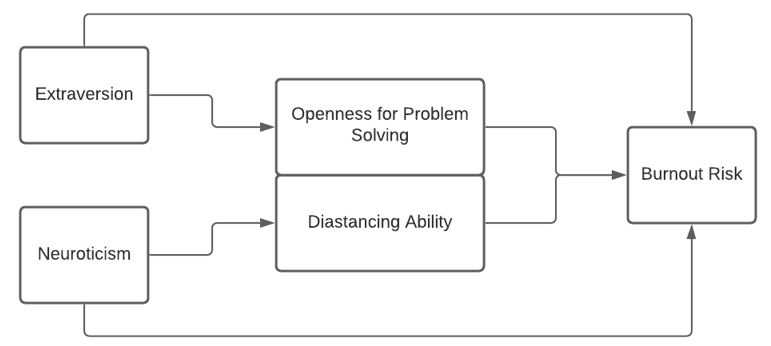

Following Wong (1993), the following mediator model (Figure 1) was tested:

Figure 1: Mediator Model.

The mediator model (Table 4) with the predictor neuroticism (based on Wong, 1993) shows a significant direct effect (.2465, p= .000) and a significant indirect effect via both avoidance tendencies namely distancing ability and openness to problem solving (.0975 and .0358, p < .05), which means that even when the mediators are held constant, the personality trait "neuroticism" has a negative influence on the risk of burnout, the interaction is also significant for both terms (neuroticism x distancing ability x risk of burnout and neuroticism x openness to problem solving x risk of burnout), which in turn means that the avoidance processes mediate the relationship between neuroticism and burnout risk.

Table 4: Model 1 (Neuroticism on Burnout Risk via Distancing Ability and Openness for Problem Solving).

The same is true for the predictor extraversion, where there is also a significant direct effect (-.0661, p= .035) and a significant indirect effect via both avoidance tendencies namely distancing ability and openness to problem solving (-.045 and -.0259, p < .05), which means that when the mediators are held constant, the personality trait "extraversion" has a positive influence on the risk of burnout and the interaction is also significant for both terms (extraversion x ability to distance oneself x risk of burnout and extraversion x openness to problems x risk of burnout), which in turn means that the avoidance processes mediate this relationship (extraversion on burnout risk), equally.

Table 5: Model 2 (Extraversion on Burnout Risk via Distancing Ability and Openness for Problem Solving).

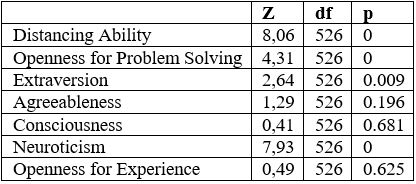

Comparing burnout patients with controls (Table 6), we found a significant difference in extraversion (z= 2.64, p= .009) and neuroticism (z= 7.93, p= .000). Burnout patients show significantly higher scores of neuroticisms and significantly lower scores of extraversions than the controls. The differences for the two avoidance processes are also significant (z= 8.06, p= .000 and z= 4.32, p= .000 respectively), the control group having the higher values on both variables.

Table 6: T-Test Results (Burnout Patients vs. Controls).

Conclusion

According to the analyses, personality traits play a subordinate role in the risk of burnout. Only neuroticism and extraversion show a direct influence on the risk of burnout, whereby only the influence of the neuroticism variable is of practical relevance. The other personality traits do not show any significant explanatory power. It seems that the (direct) influence of personality traits on the impact variables is overestimated. However, the results show that personality traits are mediated by the avoidance processes. The first implication concerns burnout prevention and related support for adaptive strategies. Since the results of the study support the theoretical presuppositions and show that poorly developed avoidance processes promote burnout, it seems sensible to promote patients' self-management and adaptive strategies; resource-oriented self-management programmers would, for instance, be suitable for this purpose.

As assumed the study shows, that poor adaptive strategies have a mediating or a direct influence on the risk of developing burnout. Therefore, action processes are, contrary to the general assumption, more important for the development of burnout than personality traits. And that is good news, because one can change certain adaption processes, like offensive problem solving or the ability to distance oneself from work, much easier than stable personality characteristics as neuroticism and extraversion. Improvements in these processes can help with job performance and stress management and can intensify the mechanisms to cope with work-related problems. Furthermore, offensive problem solving and the ability to distance oneself from work and the problems that come with it can strengthen the psychological resistance and resilience of people and thus is an important factor to stay healthy and to avoid getting burnout syndrome. Therefore, it is very important to start here and to develop strategies to help patients enhancing certain action tendencies and to gain specific resources to improve symptoms or, generally, to prevent burnout in people, who are at risk. Nevertheless, more research in this area is needed to solidify the findings from this study and to develop specific strategies, like for example resource-oriented self-management programmers, to improve adaptive strategies that help to reduce the risk of burnout and its impact on work and daily life.

References

- Scheuch K, Seibt R. Arbeits- und persönlichkeitsbedingte Beziehungen zu Burnout – eine kritische Betrachtung. In P. G. Richter, R. Rau & S. Mühlpfordt (Hrsg.), Arbeit und Gesundheit. Zum aktuellen Stand in einem Forschungs- und Praxisfeld (S. 42-54). Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers, 2007.

- Maslach C. Job Burnout: New directions in research and intervention. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 2003; 12(5): 189-192. doi:10.1111/1467- 8721.01258.

- Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP. Job Burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 2001; 52: 397-422. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397.

- Bakker, A. B. & Costa, P. L. Chronic job burnout and daily functioning: A theoretical analysis. Burnout Research, 2014; 1(3): 112-119. doi: 10.1016/j.burn.2014.04.003.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1994). Psychological stress in the workplace. In R. Crandall & P. L. Perrewé (Hrsg.), Occupational Stress: A Handbook. New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Alarcon G, Eschleman KJ, Bowling NA. Relationships between personality variables and burnout: A meta-analysis. Work & Stress, 2009; 23(3): 244-263. doi:10.1080/02678370903282600.

- Bakker AB, Van Der Zee KI, Lewig KA, Dollard MF. The relationship between the big five personality factors and burnout: A study among volunteer counselors. The Journal of Social Psychology, 2006; 146(1): 31-50. doi:10.3200/ SOCP.146.1.31-50.

- Kokkinos CM. Job stressors, personality and burnout in primary school teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 2007; 77(1): 229-243. doi:10.1348/000709905X90344

- Barford SW, Whelton WJ. Understanding burnout in child and youth care workers. Child Youth Care Forum, 2010; 39(4): 271-287. doi:10.1007/s10566-010-9104- 8.

- Manlove EE. Multiple correlates of burnout in child care workers. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 1993; 8(4): 499-518.

- Ghorpade J, Lackritz J, Singh G. Personality as a Moderator of the Relationship Between Role Conflict, Role Ambiguity, and Burnout. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 2011; 41(6): 1275-1298.

- Zawadzka AS, Kościelniak M, Zalewska AM. The big five and burnout among teachers: The moderating and mediating role of self-efficacy. Polish Psychological Bulletin, 2018; 49(2): 149-157. doi:10.24425/119482.

- Rammstedt B, Kemper CJ, Klein MC, Beierlein C, Kovaleva A. Eine kurze Skala zur Messung der fünf Dimensionen der Persönlichkeit: Big-Five-Inventory-10 (BFI-10). (GESIS-Working Papers, 2012/23). Mannheim: GESIS - Leibniz-Institut für Sozialwissenschaften, 2012.

- Schaarschmidt U, Fischer AW. Arbeitsbezogenes Verhaltens- und Erlebensmuster. Frankfurt am Main: Pearson, 2008.

- Clunies‐Ross P, Little E, Kienhuis M. Self‐reported and actual use of proactive and reactive classroom management strategies and their relationship with teacher stress and student behaviour. Educational Psychology, 2008; 28(6), 693-710.

- Heppner PP, Witty TE, Dixon WA. Problem-Solving Appraisal and Human Adjustment. The Counseling Psychologist, 2004; 32(3): 344-428.

- MacNair RR, Elliott TR. Self-perceived problem-solving ability, stress appraisal, and coping over time. Journal of Research in Personality, 1992; 26(2): 150-164.

- Heppner PP, Cook SW, Wright DM, Johnson WC. Progress in resolving problems: A problem-focused style of coping. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 1995; 42(3): 279-293.

- Heppner PP, Hibel J, Neal GW, Weinstein CL, Rabinowitz FE. Personal problem solving: A descriptive study of individual differences. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 1982; 29(6): 580-590.