Hepatocellular Adenoma in Atypical Settings: Case Report and Literature Insight on Diagnosis and Management

Bachar Amine, Khafif soukaina, Benzidane Kamal*, Essaidi Zakaria, El Abbassi Taoufik and Bensardi Fatima Zahra

Department of General Surgery, IBN ROCHD University Hospital Center, Casablanca, Morocco

Received Date: 01/05/2025; Published Date: 05/06/2025

*Corresponding author: Benzidane K, Department of General Surgery, IBN ROCHD University Hospital Center, Casablanca, Morocco

Abstract

Hepatocellular Adenoma (HCA) is a rare, benign monoclonal liver tumor arising from mature hepatocytes, most commonly seen in women aged 20–50 years with a history of estrogen-based oral contraceptive use. Although often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally on imaging, HCAs can present with nonspecific abdominal pain and carry significant risks, including hemorrhage and malignant transformation. Risk factors include hormone use, tumor size greater than 5 cm, certain genetic syndromes, metabolic disorders, and specific molecular subtypes, such as β-catenin mutations. Advances in imaging, particularly contrast-enhanced MRI, have improved diagnostic accuracy and subtype differentiation. Management strategies vary based on tumor size, patient sex, and clinical presentation, ranging from conservative surveillance to surgical resection, transarterial embolization, or radiofrequency ablation. The 2024 ACG guidelines provide a structured approach for follow-up and treatment, aiming to minimize complications and optimize patient outcomes.

Keywords: Hepatocellular adenoma; Benign liver tumor; Oral contraceptives; Hemorrhage; Malignant transformation

Introduction

Hepatocellular Adenoma (HCA) is a rare, benign liver tumor that originates from mature hepatocytes. It most commonly affects women of reproductive age, particularly those using estrogen-based oral contraceptives. Although often asymptomatic and discovered incidentally on imaging, HCAs carry potential risks including hemorrhage and malignant transformation. Understanding the clinical presentation, associated risk factors, imaging features, and current management guidelines is essential for accurate diagnosis and appropriate treatment planning.

We present the case of a hepatocellular adenoma in a 52 years old female and discuss its epidemiological features, diagnostic approach and therapeutic management in the light of the existing literature.

Case Report

A 52-year-old woman presented with right hypochondrial pain with 7 months of evolution. The patient denied fever, nausea, vomiting, jaundice, gastrointestinal or constitutional symptoms. Her past medical and family histories were irrelevant, with no history of intravenous drugs or alcohol use. She was on oral contraceptive pill for 10 years. On physical examination, she was normotensive, normocardic, with a tender abdomen, with an otherwise unremarkable examination.

Laboratory tests revealed a normal blood count and coagulation profile within normal range. The liver tests were also normal.

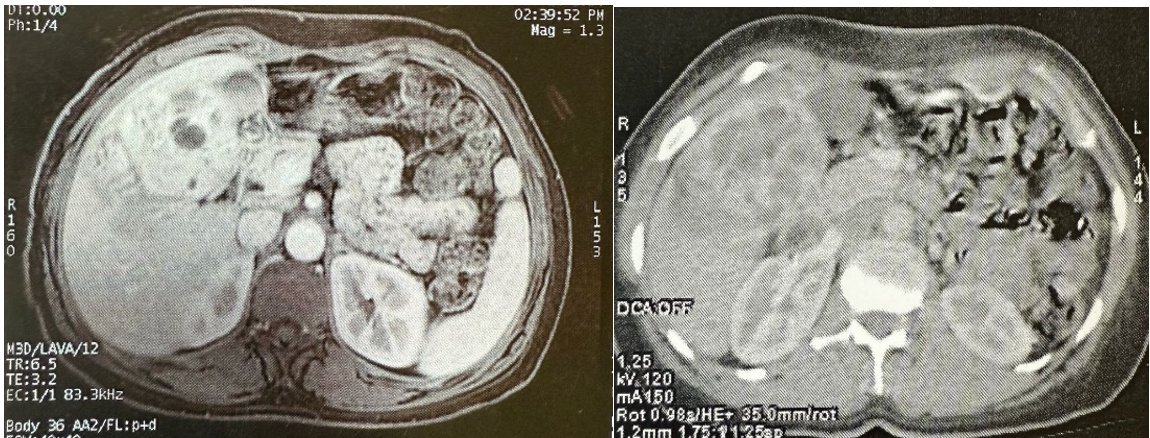

Abdominal CT scan revealed a hepatic solid cystic lesion process in segments V and VI measuring 90 x 77 x 60 mm, under the liver capsule in contact with the gallbladder without infiltrating it, and in contact with the head of the pancreas without loss of the fatty separation line suggesting a biliary cystadenoma, with no other abnormalities.

Hepatic MRI showed a voluminous hepatic mass with exophytic subhepatic development, well-limited and solid-cystic, suggesting cystadenocarcinoma or a pseudo tumoral form of hydatid cyst.

Figure 1: MRI (left) and CT scan (right) image, show the solid cystic processus in segments V and VI.

ACE, CA19.9, AFP, CA125 were normal and hydatic serology was negative.

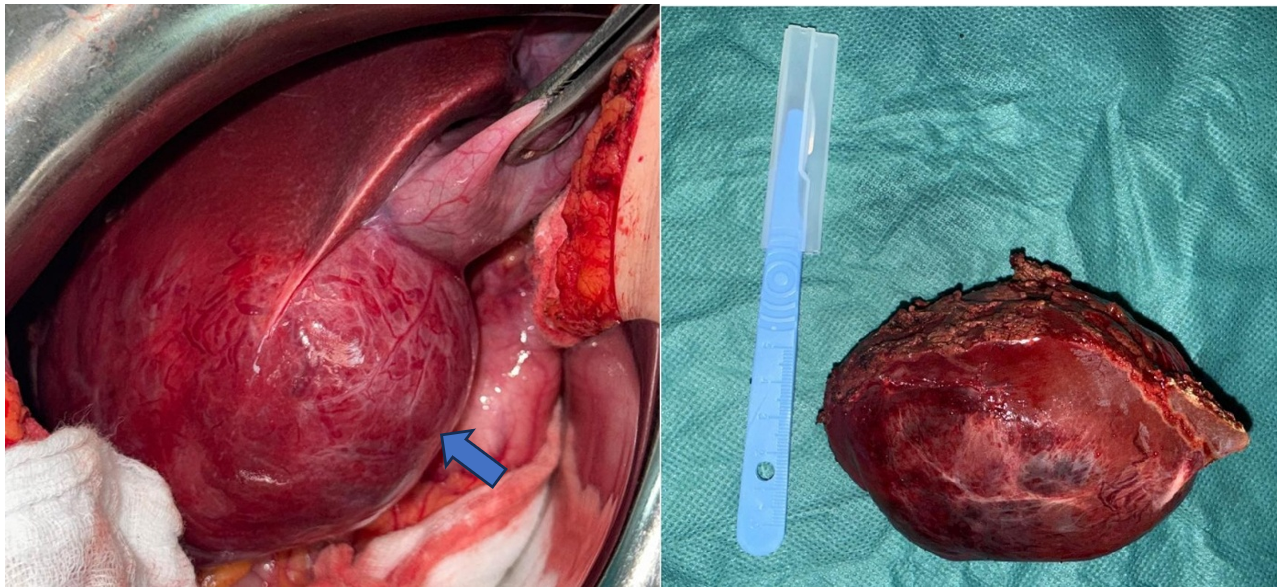

Surgical exploration revealed a solid cystic mass in segments 5 and 6 of the liver measuring 10 x 6 cm and non-adherent to adjacent organs. A bi-segmentectomy removing segments V and VI was performed.

Histopathological examination revealed the morphological and immunohistochemical features of a hepatocellular adenoma.

The patient was discharged on the fifth postoperative day.

Figure 2: Per operative image showing a solid cystic mass in segments V and VI of the liver (on left) and resected specimen (on right).

Discussion

Hepatocellular Adenoma (HCA) is a benign monoclonal tumor originating from mature hepatocytes [2]. It typically presents with nonspecific symptoms, and is most commonly seen in women aged between 20- and 50-years taking estrogen-based contraceptives [3]. The diagnosis is usually done incidentally on abdominal imaging [1].

It occurs predominantly in women of reproductive age, with a reported female: male ratio of 10:1 [1]. HCA is also associated with genetic syndromes, including glycogen storage disease type I and type III, with frequencies of 22–75% and 25%, respectively, and familial adenomatous polyposis [1,4,5].

Rarer associations include MODY3 diabetes and McCune-Albright syndrome [5], as well as conditions involving high levels of endogenous androgens or estrogens. In recent years, metabolic syndrome and obesity are also emerging as risk factors [1].

The molecular classification identifying 4 subtypes of adenomas where the B-catenin mutated subtype accounts for 10%-15%. B-catenin mutations have also been identified in hepatocellular carcinomas related to hepatitis C virus infections. These mutations are associated to an increased risk of bleeding and malignant transformation [6].

The clinical presentation is heterogeneous. Most HCA is found incidentally on abdominal imaging. When they are symptomatic, the most common presentation is mild and nonspecific right hypochondrial pain, observed in 37% of patients. However, the pain may be severe as a result of bleeding [7].

While hemorrhage is an infrequent complication associated with hepatic tumors, HCA ranks as the second most prevalent tumor connected with bleeding, following hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), with up to 30% of HCA patients experiencing spontaneous bleeding [1]. When bleeding occurs, it may be intratumoral or the tumor may rupture, leading to subcapsular or intraperitoneal hemorrhage presenting as an acute hemoperitoneum. Hemodynamic instability occurs in fewer than 10% of cases and is more commonly observed in patients with intraperitoneal bleeding rather than intratumoral bleeding, in contrast to the presented case [1].

Rupture is more likely in patients with large (>5 cm), solitary, and superficial tumors. Additional risk factors include inflammatory subtype, hormone use, and pregnancy [8]. Our patient presented multiple risk factors associated with a higher bleeding risk, namely, the size, hormone use, and HCA subtype.

HCA also has a risk of malignant transformation. Surgical series report a 4–10% incidence of HCC within resected adenomas. Known risk factors include activating mutations in β-catenin, occurring in up to 5–10% of cases, male gender, and tumor diameter larger than 5 cm [1].

Recent advancements in contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) have enhanced the role of imaging in diagnosing hepatocellular adenomas (HCAs), particularly in identifying specific subtypes and distinguishing them from other diagnosis [9].

The MRI appearance often exhibit hyperintense, heterogeneous signals on T1- and T2-weighted images due to intratumoral lipids that help to differentiate them from focal nodular hyperplasia (FNH). Hemorrhagic HCAs may also demonstrate hyperintense T1 signals with subcapsular hemosiderin rings [10,11].

Specialized MRI contrast agents enhance lesion characterization. Kupffer cell–specific agents—such as superparamagnetic iron oxides (SPIOs) and ultra-small SPIOs (USPIOs)—typically show no uptake in HCAs due to the absence of endothelial-reticular cells, resulting in decreased T2 signal intensity. Gadolinium-enhanced dynamic gradient-echo MRI may reveal early arterial enhancement and peritumoral vessels, which are characteristic of HCA [12,13].

Others MRI contrast agents, like gadoxetic acid was found to be the most cost-effective approach in a 2018 study, although its diagnostic accuracy was comparable to conventional MRI [14].

On non-contrast CT scans, HCAs typically present as well-circumscribed, low-density masses without lobulated contours and reveals after contrast agents’ injection an early peripheral enhancement with a centripetal filling pattern during the portal venous phase, which usually transitions to isodensity in the portal or delayed phase. Although uncommon, central necrosis or calcifications may also be observed [12,15].

To aid in the evaluation of incidental liver lesions detected during CT scans performed for unrelated reasons, the American College of Radiology (ACR) has developed an algorithm for use in asymptomatic adults (≥18 years old). This algorithm is stratified based on the patient's risk level for hepatic malignancy (low vs. high). However, it is not intended for cases where CT was ordered to assess known or suspected hepatic pathology. Additionally, if associated findings such as vascular invasion, biliary dilation, or adenopathy are present, direct referral for oncologic evaluation is recommended [16].

Hepatic adenomas smaller than 5 cm and associated with oral contraceptive use are typically managed conservatively by discontinuing oral contraceptives, combined with regular imaging follow-up [17].

For surveillance, and according to the 2024 American College of Gastroenterology (ACG) guidelines, women with HCAs smaller than 5 cm should undergo computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) every 6 to 12 months for at least two years. After that, ultrasound may be considered for ongoing surveillance; however, contrast-enhanced CT or MRI remains necessary if any changes in the adenomas are detected [17].

Surgical resection, which does not require wide surgical margins or regional lymphadenectomy, is recommended for all male patients regardless of tumor size, and for women with tumors larger than 5 cm [18].

Transarterial Embolization (TAE) is the preferred treatment for HCAs complicated by hemorrhage and may be followed by elective surgical resection [19].

Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) is typically considered for adenomas smaller than 4 cm and is reserved for non-surgical candidates, those with hormone-sensitive tumors, underlying liver disease, or women planning pregnancy [19].

Conclusion

Hepatocellular Adenoma (HCA) is a rare, benign liver tumor predominantly affecting women of reproductive age, often linked to hormone use and metabolic risk factors. While many HCAs are asymptomatic and discovered incidentally, they carry risks of hemorrhage and malignant transformation, especially in larger or genetically predisposed cases. Advances in imaging have improved diagnostic accuracy and subtype identification, guiding personalized management strategies that range from conservative surveillance to surgical intervention or minimally invasive therapies, depending on individual risk factors and tumor characteristics.

References

- Lopes SR, Santos IC, Teixeira M, Sequeira C, Carvalho AM, Gamito É. Hepatocellular Adenoma: A Life-Threatening Presentation of a Rare Liver Tumor – Case Report and Literature Review. GE Port J Gastroenterol, 2024; 31(6): 443-448. doi:10.1159/000538340

- Huang J, Xu D, Li A. Laparoscopic hepatectomy for hepatocellular adenoma using the hepatic vein as anatomic markers: How I do it (with video). Asian J Surg, 2024; 47(12): 5143-5146. doi:10.1016/j.asjsur.2024.04.032

- Benign liver tumours: understanding molecular physiology to adapt clinical management | Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2025.

- Agrawal S, Agarwal S, Arnason T, Saini S, Belghiti J. Management of Hepatocellular Adenoma: Recent Advances. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2015; 13(7): 1221-1230. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.023

- EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of benign liver tumours. J Hepatol, 2016; 65(2): 386-398. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.04.001

- El Ouardi W, El Mansoury FZ, Labbioui R, Benazzouz M. Hepatocellular adenoma with activation of the β-catenin mutation pathway mimicking intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma: Case report. Radiol Case Rep, 2024; 20(1): 521-524. doi:10.1016/j.radcr.2024.10.061

- Nault JC, Couchy G, Balabaud C, et al. Molecular Classification of Hepatocellular Adenoma Associates With Risk Factors, Bleeding, and Malignant Transformation. Gastroenterology, 2017; 152(4): 880-894.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.11.042

- Agrawal S, Agarwal S, Arnason T, Saini S, Belghiti J. Management of Hepatocellular Adenoma: Recent Advances. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2015; 13(7): 1221-1230. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.05.023

- Shaked O, Siegelman ES, Olthoff K, Reddy KR. Biologic and clinical features of benign solid and cystic lesions of the liver. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2011; 9(7): 547-562.e1-4.

- Bieze M, van den Esschert JW, Nio CY, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of MRI in differentiating hepatocellular adenoma from focal nodular hyperplasia: prospective study of the additional value of gadoxetate disodium. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2012; 199(1): 26-34.

- van Aalten SM, Thomeer MG, Terkivatan T, et al. Hepatocellular adenomas: correlation of MR imaging findings with pathologic subtype classification. Radiology, 2011; 261(1): 172-181.

- Grazioli L, Federle MP, Brancatelli G, Ichikawa T, Olivetti L, Blachar A. Hepatic adenomas: imaging and pathologic findings. Radiographics, 2001; 21(4): 877-894.

- Chung KY, Mayo-Smith WW, Saini S, Rahmouni A, Golli M, Mathieu D. Hepatocellular adenoma: MR imaging features with pathologic correlation. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 1995; 165(2): 303-308.

- Suh CH, Kim KW, Park SH, et al. A cost-effectiveness analysis of the diagnostic strategies for differentiating focal nodular hyperplasia from hepatocellular adenoma. Eur Radiol, 2018; 28(1): 214-225.

- Ichikawa T, Federle MP, Grazioli L, Nalesnik M. Hepatocellular adenoma: multiphasic CT and histopathologic findings in 25 patients. Radiology, 2000; 214(3): 861-868.

- Gore RM, Pickhardt PJ, Mortele KJ, Fishman EK, Horowitz JM, Fimmel CJ, et al. Management of Incidental Liver Lesions on CT: A White Paper of the ACR Incidental Findings Committee. J Am Coll Radiol, 2017; 11: 1429-1437.

- Frenette C, Mendiratta-Lala M, Salgia R, Wong RJ, Sauer BG, Pillai A. ACG Clinical Guideline: Focal Liver Lesions. Am J Gastroenterol, 2024; 119 (7): 1235-1271.

- Farges O, Ferreira N, Dokmak S, Belghiti J, Bedossa P, Paradis V. Changing trends in malignant transformation of hepatocellular adenoma. Gut, 2011; 60(1): 85-89.

- Shreenath AP, Grant LM, Kahloon A. Hepatocellular Adenoma. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2025.