Prevalence of HCV Among Hemodialysis Patients at a Kidney Center, Gujrat: A Gender-Based Comparative Analysis

Nimra Zahoor1, Aqna Malik1,2,*, Madiha Zaman3, Faiqa shahbaz1, Nida Fatima1 and Muhammad Ahsaan Ullah Mustafa4

1Department of Pharmacy, University of Chenab, Gujrat, Pakistan

2Department of Pharmacy, University of Lahore, Lahore, Pakistan

3Department of Pharmacy, Lahore College and Women University Lahore (LCWU), Pakistan

4Department of Pharmacy, University of Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan

Received Date: 10/04/2025; Published Date: 20/05/2025

*Corresponding author: Dr. Aqna Malik, Department of Pharmacy, University of Chenab, Gujrat; Department of Pharmacy, University of Lahore, Lahore, Pakistan

Abstract

Background: The harmful Hepatitis C virus (HCV) causes a severe liver disease known as hepatitis C. When it comes to Pakistani health, HCV is a big deal. People on long-term hemodialysis often get hepatitis C, the most common hepatotropic virus infection. Because they undergo dialysis treatments so frequently, hemodialysis patients are more vulnerable to HCV infection.

Objective: To compare the prevalence of HCV in male and female hemodialysis patients at a kidney center in Gujrat.

Methodology: This data is retrospective data and was collected in coordination with the staff of Kidney Centre Gujrat, where they provided reports of several hemodialysis patients with HCV positive and negative. It consists of 188 patients including males and females of all age groups that were referred in the Kidney Centre Gujrat. The study duration was 3 months i.e., from 10 November 2023 to 10 February 2024. Demographic information, duration of treatment, state of illness, and other parameters regarding patients admitted to a healthcare facility of hemodialysis were determined

Results: Among 188 participants of the study, most affected patients with HCV were in the age range of 30-59 years. 80/188 (42.55%) were HCV+ including 36/188 (19.14%) females and 54/188 (28.72%) males. Prevalence of HCV+ in hemodialysis patients was higher in males (8.8 ± 7.9) than females 6 ± 4.6 while HCV- cases were less in females 5.3 ± 4.4. as compared to males (11± 5.3). The overall ratio of HCV is greater in males as compared to females.

Conclusion: The herpes simplex virus does not impact men and women in the same proportions. When compared to female hemodialysis patients, the ratio of male patients with HCV is higher. The results also show that males have a higher ratio of hypertension to comorbidities and adverse effects.

Keywords: Chronic kidney disease; Hemodialysis; Hepatitis C virus; End-stage renal disease

Background

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is a prominent cause of liver damage among chronic renal failure (CRF) patients who receive maintenance hemodialysis [1].

Hemodialysis is an extracorporeal procedure in which a semipermeable membrane removes uremic retention products from the blood to cleanse it [2]. Worldwide, hemodialysis is the most common kind of renal replacement therapy for individuals with end-stage kidney disease [3]. The DOPPS data also shown a correlation between HCV infection and worse quality of life scores, increased hospitalization and death rates in hemodialysis patients [7]. Hemodialysis is the commonest form of kidney replacement therapy in the world corresponding to over 89% of dialysis treatments and roughly 69% of total kidney replacement therapies. Both dialysis technology and patient access to the treatment have significantly improved over the past 60 years since the beginning of HD, especially in high-income nations [8]. In previous studies gender-specific stratified analysis revealed that the pooled prevalence of HCV in male hemodialysis patients was 33.92% and the pooled prevalence of HCV in female hemodialysis patients was 33.85%. The results were not statistically significant. A notable variation was noted between provinces across regions: Punjab had a higher pooled prevalence of HCV in hemodialysis patients (37.51%); than Baluchistan (34.42%), Sindh (27.11%), and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (22.61%) [13]. In the 50 and older age group, the prevalence of males with HBV positive is 2.456 times higher than that of females, with a significant difference (P= 0.021*). Ultimately, it is determined that the age group 50 years of age and above was shown to be statistically significant and to be more affected by HBV and HCV [11]. The primary causes of HCV infection include intravenous drug use, dangerous medical procedures, and the use of unsterile materials in activities such as tattooing and acupuncture. There is minimal sexual and domestic transmission. The yearly risk of dialysis is predicted to be 2%. The prevalence of HCV infection in patients with HD varies widely around the globe, ranging from 1% to 90% [26].

Aims and objectives

Aims: This current study is focused on finding the prevalence of HCV in hemodialysis patient among males and females in kidney center Gujrat.

Objective: To compare the prevalence of HCV in both male and female hemodialysis patient at Kidney Center Gujrat

Methodology

Study Design: A retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted

Settings: Cinical study data and was collected in coordination with the staff of Kidney Centre Gujrat, where they provided reports of several hemodialysis patients with HCV positive and negative.

Study Duration: 3 months i.e., from 10th November 2023 – 10th February 2024.

Sample Size: Consists of 188 patients including males and females of all the age groups that were referred in the Kidney Centre Gujrat.

Sampling Technique: Stratified sampling technique

Data Collection Tools: Medical Reports of the patients were collected and observed from the Kidney Centre to study different parameters of CKD of the number of hemodialysis patients.

Data Collection Procedure:All the regulations set by the University of Chenab and hospital authorities have followed while collecting the reports. Written Consent signed from the health staff of hospital (kidney center) and department of pharmacy of respective institute (The University of Chenab) ensuring that data was merely for the research purpose and for the benefit and knowledge of the patients.

Data Analysis: Data was analyzed by applying statistical tools i.e., mode, mean, frequencies, standard deviation to explain the numeric values and to generate the tables and the graphs.

Ethical Consideration: All the rules and regulations made by the ethical committee of the University of Chenab were followed while conducting this research. Consents obtained and all the information collected from the patients was kept in laptop. Patients were personally briefed about the positive outcomes of this study. Withdrawal rights were given to the patients/participants.

Results

Age wise distribution among dialysis patients

There were 188 patients out of which 63.8% were males and 36.1% were females. The male to female ratio was 0.98: 1.0, with 68/188 (36.17%) and 120/188 (63.8%) of the patients being male. We divided the patients into five age groups 19-29, 30-39, 40-49, 50-59, 60-69 and ≥70. There were 15.43% patients in the 19-29 age group, 29.26% in the 30-39, and 21.28% in the 40-49, 20.21% in the 50-59, 10.64% in the 60-69 and 3.19% in the ≥70 age group. The highest percentage of patients was found in the age group of 30-39 (29.26).

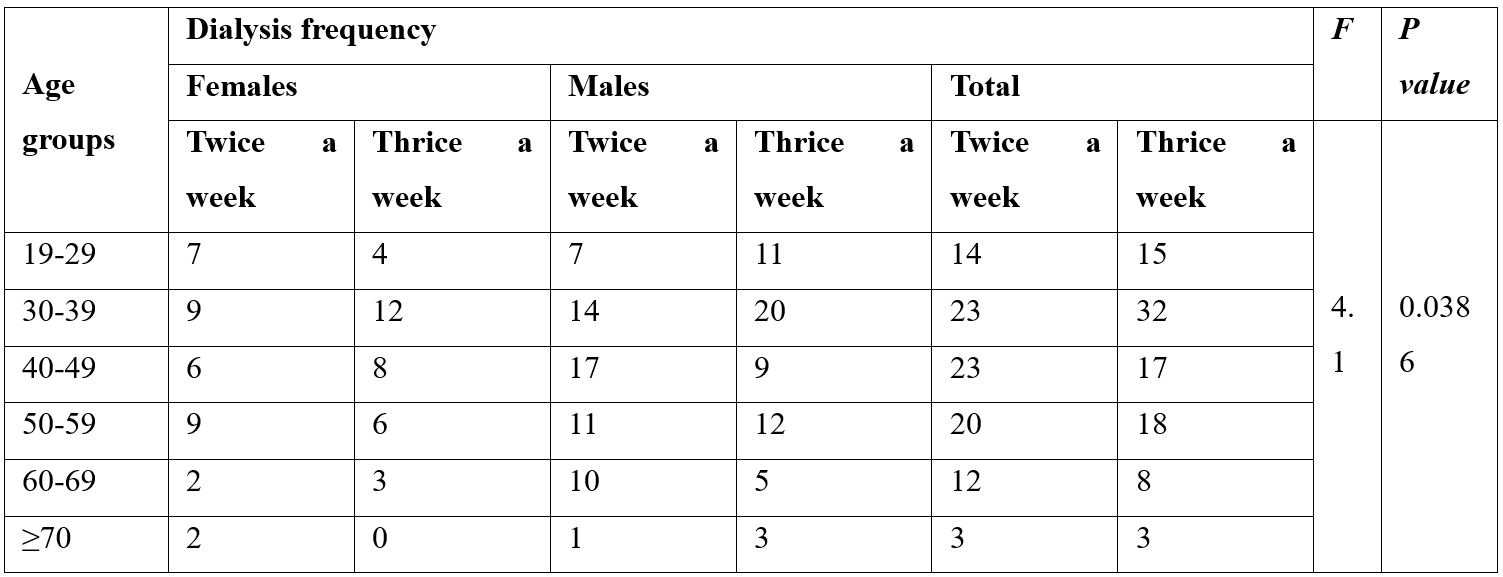

Table 1: Frequency of dialysis among hemodialysis patients.

Dialysis frequency in Females found significantly differ from total with adjusted (p= 0.0311). The overall ratio of dialysis frequency in males is greater as compared to females.

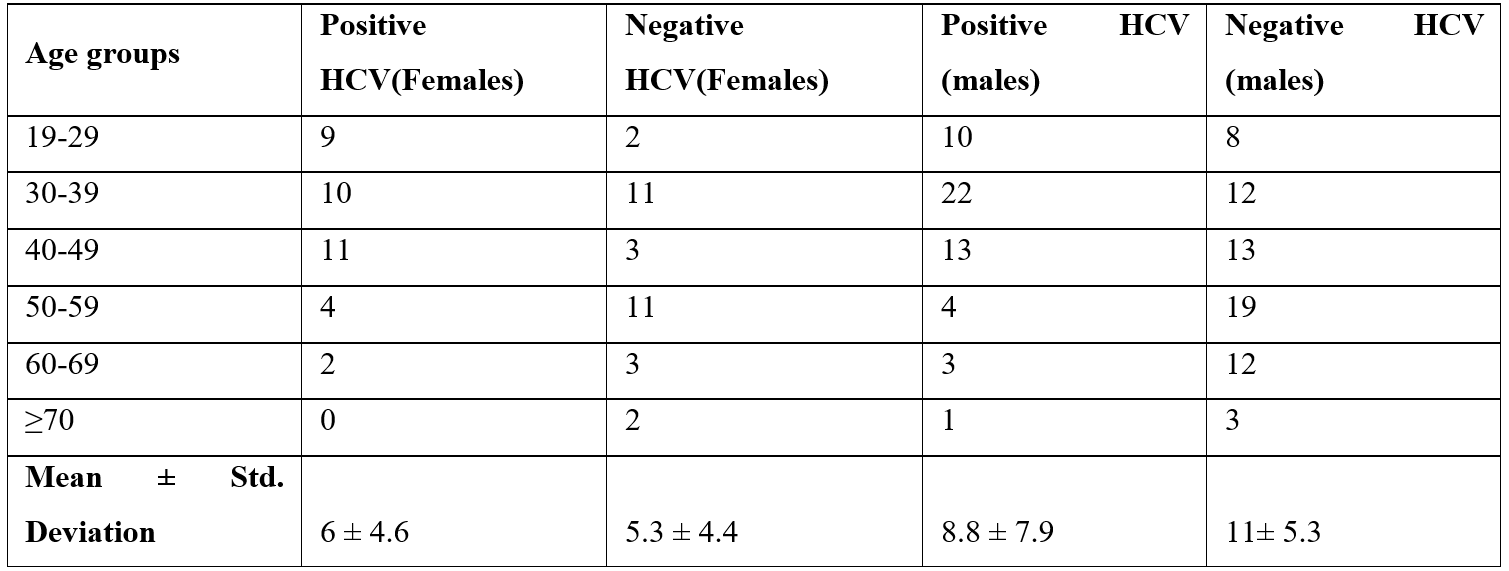

Prevalence of HCV in hemodialysis patients

In the 50 and older age group, the prevalence of males with HCV positive is 2.456 times higher than that of females, with a significant difference (P= 0.021*). Ultimately, it is determined that the age group 50 years of age and above was shown to be statistically significant and to be more affected by HBV and HCV [11].

Table 2: Comorbidities among hemodialysis patients.

Age-related blood pressure patterns among hemodialysis patients

Among 188 patients, mostly males had stage 2 hypertension common range of 19-69 years. While females has stage-2 HTN most commonly in age range 30-59 years and less in ≥70 years. The ratio of hypertension is greater in males as compared to the females.

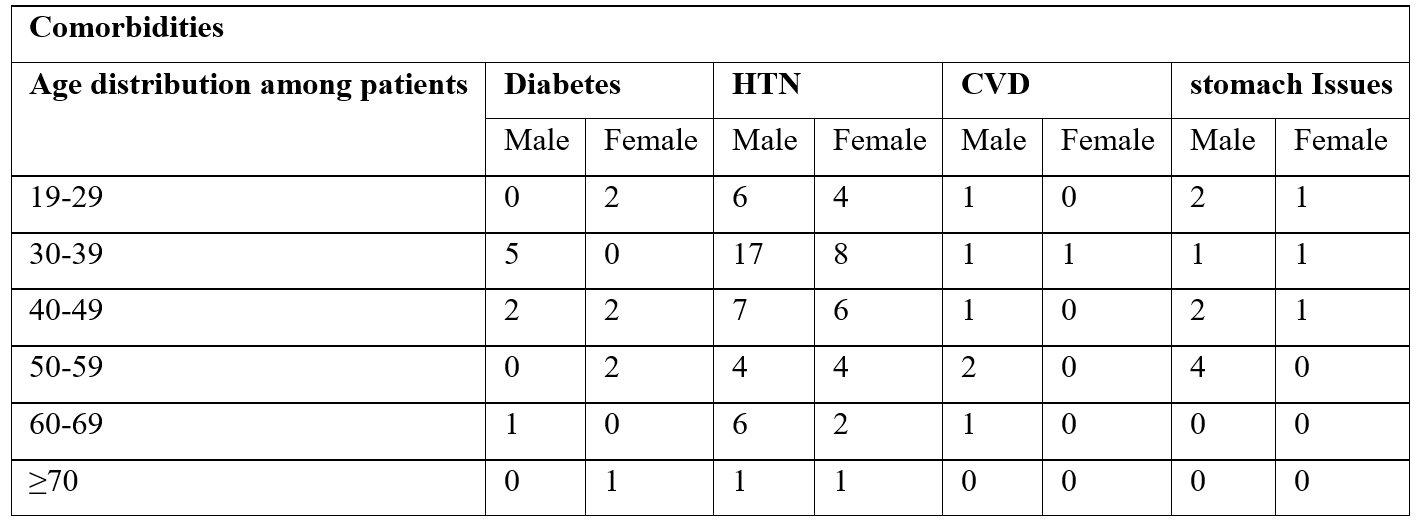

Table 3: Comorbidities among hemodialysis patients.

Among 69% of the male participants with comorbidities, 7% had diabetes as the reason for end-stage renal disease (ESRD), 34% had a history of hypertension and 5% had a cardiovascular disease (CVD) in age range of 30-39 years. While among 36% of the female participants with comorbidities 10% had diabetes as the cause of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), 37% had a history of HTN and 1% had cardiovascular disease (CVD). Most of the females had hypertension followed by the diabetes and cardiovascular disease. The ratio of hypertension is greater in males as compared to the females and more prevalent in age group 30-39 along with the highest mean age of 43 [32]. Diabetic nephropathy accounts for 48.8% of cases of end-stage renal disease (ESRD), while hypertensive nephropathy accounts for 19.8% of newly diagnosed patients. These findings highlight the significance of managing hypertension and diabetes in ESRD (Park, Oh, & Kang, 2013).

Common side effects observed by hemodialysis patients

Among 188 patients, 63.8% males 36.1% female observed side effects. Among males, the greatest and frequent reported problems during hemodialysis were muscle pruritus (20.5%) and depression (6%), respectively. Only 4.4% patients had body pain and the severity of pain varies from severe, moderate to mild. 7.3% patients had lack of appetite (Akhyani, Ganji, Samadi, Khamesan, & Daneshpazhooh, 2005). While female patients had pruritus (18.3%), followed by depression (12.5%), body pain (10%) and lack of appetite (5.8%). The age group in which side effects are more common is 40-49 years. Side effects are more common in males as compared to females.

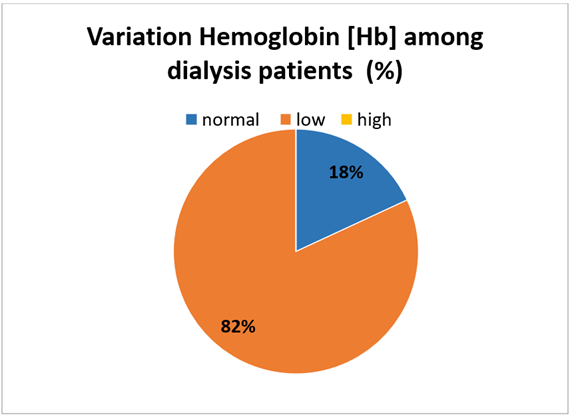

Figure 1: Hb variability in hemodialysis patients.

Among 188 patients. The mean age of participants was 43 years and the majority of patients (63.8%) were male. Among patients 82% had lower Hb level (<12 g/dL) and only 18% had normal Hb level (12-18 g/dL). The low Hb level was associated with anemia which was a major risk factor in hemodialysis patients.

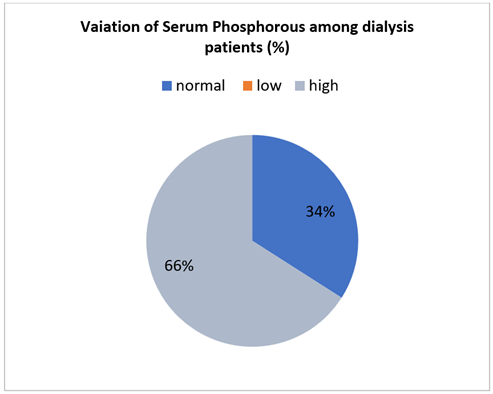

Serum phosphorous variation in hemodialysis patients

Figure 2: Variability of serum phosphorous among hemodialysis patients.

The normal serum phosphorous concentration in blood is 2.4-4.9 mg/dl. 66% of patients had high level of phosphorous which is greater than 4.9mg/dl and 34% of patients had serum phosphorous level within the normal range. The average phosphorous level in patients was 6.5 mg/dl. We found that a significant portion of hemodialysis patients who have been on dialysis for at least a year has serum phosphorus levels exceeding 6.5 mg/dL. When the product of serum calcium and phosphorus (Ca x PO4) is raised, hyperphosphatemia can lead to the development and progression of secondary hyperparathyroidism as well as an increased risk of metastatic calcification. The significant morbidity and mortality rates observed in ESRD patients could be attributed to either of these disorders (Block, Hulbert-Shearon, Levin, & Port, 1998). Reduced all-cause mortality was linked to a low serum phosphorus level (<3.5 mg/dL) only in older patients (≥65 years old), not in younger patients (<65 years old). While hypophosphatemia is only linked to higher mortality in older MHD patients, hyperphosphatemia and mortality are similar across all age groups of MHD patients. Future research must look into whether keeping older dialysis patients' serum phosphorus levels from falling too low is linked to improved results (Lertdumrongluk et al., 2013).

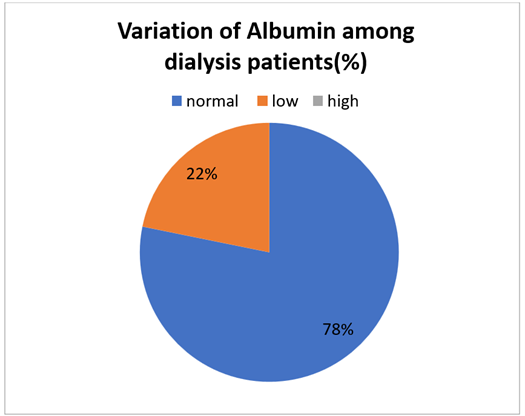

Serum albumin variability among hemodialysis patients

Figure 3: Variability of serum albumin among hemodialysis patients.

We collected data from 188 patients who were undergoing hemodialysis, out of which 22% patients had low serum albumin level (<3.8g/dl) while 78% patients had normal serum albumin level between 3.8-5.1 g/dl.

In hemodialysis (HD) patients, lower serum albumin concentrations are predictive with higher mortality. Patients on maintenance HD may have different serum albumin concentrations due to variations in the volume of distribution, synthesis rate, or elimination rate of albumin. Less food intake causes synthesis to be down-regulated, which is why reduced serum albumin is frequently suggested as a visceral-protein diagnostic for protein-energy malnutrition (Iseki, Kawazoe, & Fukiyama, 1993). At the onset of the study, 39% of all patients had serum albumin levels below 3.7 g/dL. Other nutritional surrogates, such as predialysis creatinine (r = 0.36), predialysis BUN (r = 0.16), serum phosphorus (r = 0.12), and serum cholesterol (r = 0.08), exhibited a substantial connection (P < 0.001) with serum albumin (Leavey et al., 2000).

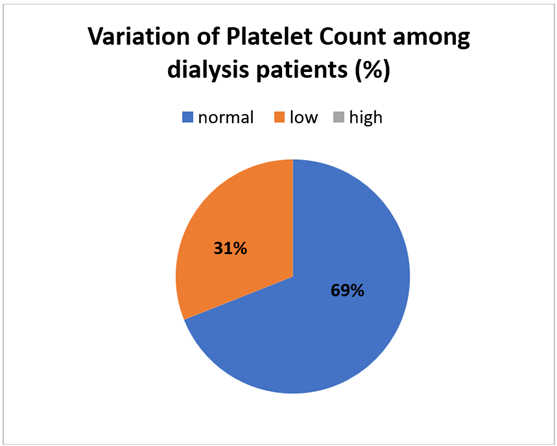

Platelet count variation in hemodialysis patients

Figure Variability of platelet count among hemodialysis patients

Among patients 31% had a platelet count below 150000/mm while 69% patients had a platelet count between 150000-450000/mm. The platelet count usually decreases during the first 15–30 minutes of dialysis, usually by 5–15%. By the end of the dialysis session, the platelet counts almost always either reaches the pre-dialysis level again or slightly exceeds it. Additionally, it was noted that following HD, the majority of hematological parameters increased. More importantly, it was discovered that post-HD, platelet counts decreased concurrently with increases in PT, APTT, and fibrinogen (Alghythan & Alsaeed, 2012). Platelet counts in hemodialysis patients are often lower than those in healthy controls, ranging from 175 to 180,000/mm3. The only paper that looked into platelet survival in hemodialysis patients was published in 1967; However it is believed to be of normal duration in these patients. The reticulated platelet count, a gauge of thrombopoiesis, is lower even with increased thrombopoietin levels, even while the number of megakaryocytes in the bone marrow is normal (Daugirdas & Bernardo, 2012).

Summary

The above study tells us about the gender wise ratio of ESRD patients with or without HCV. The natural history of hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in dialysis is not fully understood while the clinical outcome differs from that of the general population. HD patients show a milder liver disease with lower aminotransferase levels. Studies show that patients on hemodialysis have various comorbid diseases like diabetes, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and stomach issues. Blood glucose levels can vary widely due to the different and opposing effects of ESRD and dialysis. Hypertension is common in chronic kidney disease patients and mostly ESRD patients have hypertension. Systolic hypertension is more common as compared to the diastolic hypertension in hemodialysis patients. This study also tells about the common side effects of the hemodialysis such as pruritus, body pain, depression and lack of appetite. Pruritus is common outcome of the dialysis. According to the above mention data the ratio of the females having ESRD is greater as compared to the males.

Limitations:

The limitation of above studies is that the data is collected from the laboratory reports only. There is no prescription data included in this study. The data collected from the laboratory reports tells us only about the lab values of ESRD patients. There is no information about the medication of ESRD patients on hemodialysis included in this study.

Conclusion

Both genders are not equally affected by the HCV. The ratio of the male patients is lesser than the ratio of females’ patients on hemodialysis with HCV. It is also concluded that the ratio of hypertension, comorbidities and sides effects is also higher in males than females.

References

- Alavian SM, Einollahi B, Hajarizadeh B, Bakhtiari S, Nafar M, Ahrabi S. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection and related risk factors among Iranian haemodialysis patients. Nephrology, 2003; 8(5): 256-260.

- Ulijn RV, Bibi N, Jayawarna V, Thornton PD, Todd SJ, Mart RJ, et al. Bioresponsive hydrogels. Materials today, 2007; 10(4): 40-48.

- Thurlow JS, Joshi M, Yan G, Norris KC, Agodoa LY, Yuan CM, et al. Global epidemiology of end-stage kidney disease and disparities in kidney replacement therapy. American journal of nephrology, 2021; 52(2): 98-107.

- Jeffers LJ, Perez GO, De Medina MD, Ortiz-Interian CJ, Schiff ER, Reddy KR, et al. Hepatitis C infection in two urban hemodialysis units. Kidney international, 1990; 38(2): 320-322.

- Fissell RB, Bragg-Gresham JL, Woods JD, Jadoul M, Gillespie B, Hedderwick SA, et al. Patterns of hepatitis C prevalence and seroconversion in hemodialysis units from three continents: the DOPPS. Kidney international, 2004; 65(6): 2335-2342.

- Goodkin DA, Bieber B, Gillespie B, Robinson BM, Jadoul M. Hepatitis C infection is very rarely treated among hemodialysis patients. American journal of nephrology, 2013; 38(5): 405-412.

- Goodkin DA, Bieber B, Jadoul M, Martin P, Kanda E, Pisoni RL. Mortality, hospitalization, and quality of life among patients with hepatitis C infection on hemodialysis. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 2017; 12(2): 287-297.

- Bello AK, Okpechi IG, Osman MA, Cho Y, Htay H, Jha V, et al. Epidemiology of haemodialysis outcomes. Nature Reviews Nephrology, 2022; 18(6): 378-395.

- Ashkani-Esfahani S, Alavian SM, Salehi-Marzijarani M. Prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection among hemodialysis patients in the Middle-East: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World journal of gastroenterology, 2017; 23(1): 151.

- El-Ottol AE-kY, Elmanama AA, Ayesh BM. Prevalence and risk factors of hepatitis B and C viruses among haemodialysis patients in Gaza strip, Palestine. Virology journal, 2010; 7: 1-7.

- Ali A, Khan GN, Salman M, Khan MN, Ullah A, Khan AH, et al. Investigation of Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C in the blood of hemodialysis patients from Peshawar, Pakistan. Research Square, 2020. https://dx.doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-36829/v1

- Abbas HN, Rabbani MA, Safdar N, Murtaza G, Maria Q, Ahamd A. Biochemical nutritional parameters and their impact on hemodialysis efficiency. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation, 2009; 20(6): 1105-1109.

- Akhtar S, Nasir JA, Usman M, Sarwar A, Majeed R, Billah B. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus in hemodialysis patients in Pakistan: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS one, 2020; 15(5): e0232931.

- Al-Jiffri AMY, Fadag RB, Ghabrah TM, Ibrahim A. Hepatitis C virus infection among patients on hemodialysis in Jeddah: a single center experience. Saudi Journal of Kidney Diseases and Transplantation, 2003; 14(1): 84-89.

- Ali I, Siddique L, Rehman LU, Khan NU, Iqbal A, Munir I, et al. Prevalence of HCV among the high risk groups in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. Virology journal, 2011; 8: 1-4.

- Ali Jaffar Naqvi S. Nephrology services in Pakistan. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation, 2000; 15(6): 769-771.

- Alter MJ, Arduino MJ, Lyerla HC, Miller ER, Tokars JI. Recommendations for preventing transmission of infections among chronic hemodialysis patients, 2001.

- Anees M, Sarwar N, Ahmad S, Elahii I, Mateen F. Factors associated with seroconversion of hepatitis C virus in end stage renal disease patients. J Coll Physicians Surgeons Pakistan, 2021; 31(09): 1040-1045.

- Caragea DC, Mihailovici AR, Streba CT, Schenker M, Ungureanu B, Caragea IN, et al. Hepatitis C infection in hemodialysis patients. Current health sciences journal, 2018; 44(2): 107.

- Fabrizi F, Messa P. The epidemiology of HCV infection in patients with advanced CKD/ESRD: A global perspective. Paper presented at the Seminars in dialysis, 2019.

- Huma MM, Siddiqui DM, Bashir DB, Ali DSF, Baloch DAA, Masroor DM. Hemodialysis patients profile at Dow University of Health Sciences. Pakistan Journal of Medical Sciences, 2014; 30(6). doi:10.12669/pjms.306.5364

- Jadoul M, Bieber BA, Martin P, Akiba T, Nwankwo C, Arduino JM, et al. Prevalence, incidence, and risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection in hemodialysis patients. Kidney International, 2019; 95(4): 939-947. doi:10.1016/j.kint.2018.11.038

- Khakurel S, Agrawal RK, Hada R. Pattern of end stage renal disease in a tertiary care center, 2009.

- Khan S, Attaullah S, Ali I, Ayaz S, Naseemullah Khan SN, et al. Rising burden of Hepatitis C Virus in hemodialysis patients. Virology Journal, 2011; 8(1): 438. doi:10.1186/1743-422x-8-438.

- Khokhar N, Alam AY, Naz F, Mahmud SN. Risk factors for hepatitis C virus infection in patients on long-term hemodialysis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak, 2005; 15(6): 326-328.

- Marinaki S. Hepatitis C in hemodialysis patients. World Journal of Hepatology, 2015; 7(3): 548. doi:10.4254/wjh.v7.i3.548

- Mele, Tosti, Marzolini, Moiraghi, Ragni, Gallo, et al. Prevention of hepatitis C in Italy: lessons from surveillance of type‐specific acute viral hepatitis. Journal of viral hepatitis, 2000; 7(1): 30-35.

- Muhammad A, Zeb MA, Ullah A, Afridi IQ, Ali N. Effect of haemodialysis on haematological parameters in chronic kidney failure patients Peshawar-Pakistan. Pure and Applied Biology, 2020; 9(1): 1163-1169.

- Reddy A, Murthy K, Lakshmi V. Prevalence of HCV infection in patients on haemodialysis: survey by antibody and core antigen detection. Indian J Med Microbiol, 2005; 23(2): 106-110.

- Selcuk H, Kanbay M, Korkmaz M, Gur G, Akcay A, Arslan H, et al. Distribution of HCV Genotypes in Patients with End-Stage Renal Disease According to Type of Dialysis Treatment. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 2006; 51(8): 1420-1425. doi:10.1007/s10620-005-9025-9

- Umar M, tul Bushra H, Ahmad M, Khurram M, Usman S, Arif M, et al. Hepatitis C in Pakistan: a review of available data. Hepatitis monthly, 2010; 10(3): 205.

- Van S, Hardon A. Injection practices in the developing world. World Health Organization, 1997; 15-43.