Dysgerminoma of the Ovary: A Case Report and Review of the Literature

Dr. Bassir G*, Dr. Maali I, Pr Boufettal H, Pr Mahdaoui S and Pr Samouh N

Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, IBN ROCHD University Hospital, Casablanca, Morocco

Received Date: 11/12/2024; Published Date: 12/02/2025

*Corresponding author: Bassir G, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, IBN ROCHD University Hospital, Casablanca, Morocco

Introduction

Non-epithelial tumours of the ovary are rare. Germ cell tumours are the most common, accounting for 15-20% of ovarian tumours. They are made up of benign tumours (dermoid cysts), cancerised dermoid cysts, which are malignant tumours derived from different contingents of dermoid cysts, and finally, primitive malignant germ cell tumours. The latter represent less than 5% of all malignant tumours of the ovary, and 95% of germ cell tumours are benign cystic teratomas or dermoid cysts. With a ratio of 1:10, we report a case of germ cell tumour of the ovary in a young patient aged 28.

Observation

The patient was 28 years old, married, mother of two living children, with no particular pathological history. She had gone through menarche at the age of 12 with a regular cycle, and was on oral contraception which had been stopped one month before the operation. The patient was referred to our clinic because she had been suffering from chronic pelvic pain for six months, with no associated urinary or digestive signs, and was in good general condition. On examination, the patient was in good general condition, normotensive (110/70) and apyretic.

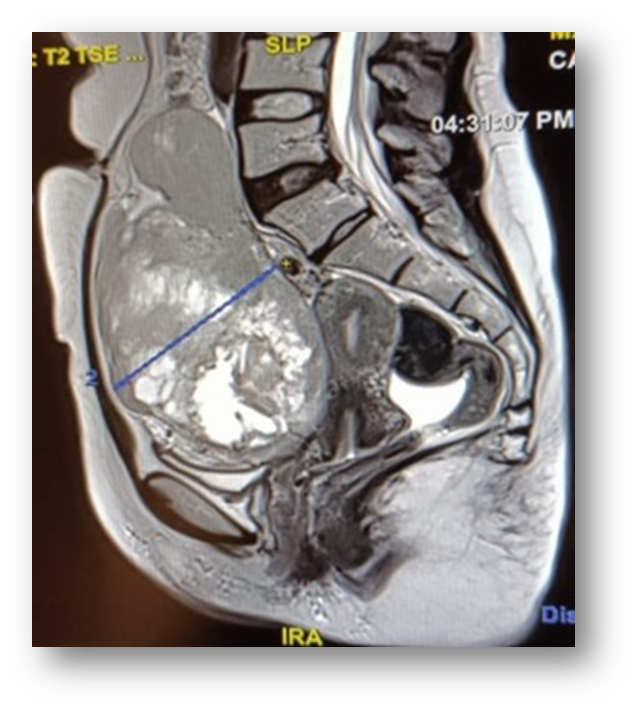

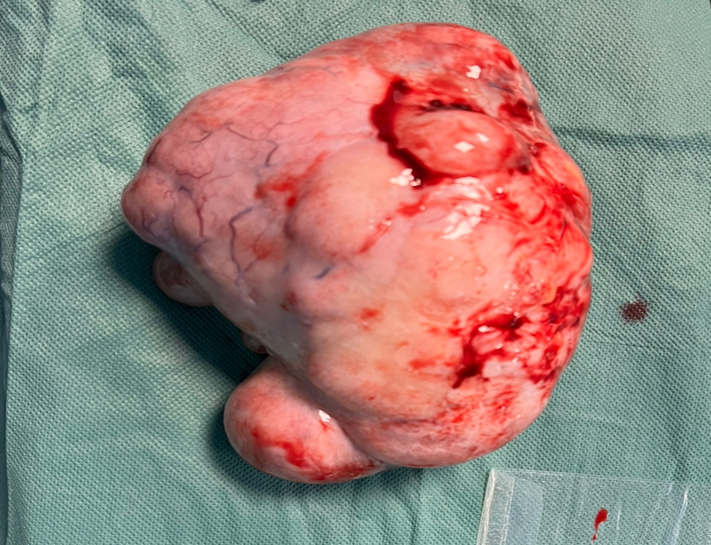

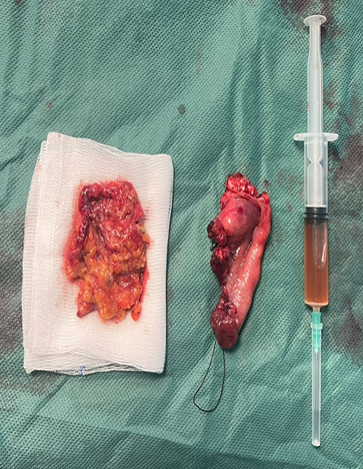

Gynaecological examination: soft abdomen with no palpable mass, speculum examination: normal cervix, no bleeding, vaginal touch: a right latero-uterine mass reaching to the umbilicus, allowing a pelvic ultrasound to be performed (Figure 1) which revealed a voluminous, hyperechoic, heterogeneous right latero-uterine formation with a few cystic cells with poor Doppler vascularity, measuring 17x17 cm with a layer of effusion at the level of the cul de sac of Douglas. A pelvic MRI (Figure 2) showed a voluminous pelvic mass measuring 18 cm, suspicious in appearance, encapsulated, oval, solidocystic with a solid component enhanced by PDC with moderate peritoneal effusion. Tumour markers: CA 125 slightly elevated at 55IU/ml, others: CA19-9, alpha-fetoprotein and CEA were within normal limits, and BHCG was negative. A chest X-ray was performed, which came back normal. A laparotomy was indicated, which revealed a moderately large peritoneal effusion and a 22 cm solidocystic right ovarian mass (Figure 3).

The left adnexa was without visible abnormality, and the right tube and uterus without pathology. The rest of the digestive examination was unremarkable. The peritoneal fluid was taken for cytological examination and a right cystectomy was carried out following examination of the anatomopathology by extemporaneous examination, which came back in favour of an undifferentiated malignant tumour. The decision was made to complete the operation with a right adnexectomy and epiploic and peritoneal biopsies, pending a definitive pathology examination using immunohistochemistry, which showed a profile compatible with a dysgerminoma. Cytological examination of the peritoneal fluid and epiploic and peritoneal biopsies did not reveal any cells suspected of malignancy. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 4 in good condition. The patient was referred to the oncology department for further management.

Figure 1: Pelvic ultrasound.

Figure 2 & 3: Surgical specimen sent for anamatopathological examination.

Discussion

These tumours differ from adenocarcinomas in a number of respects: much earlier age of onset, since they are tumours of the girl and young woman (average age between 18 and 21 years, depending on the series) [1-2], diagnosis at an earlier stage (approximately 70 to 80% of stage I disease), much better prognosis, very high chemosensitivity, specific markers that differ according to histological type and specific therapeutic methods. Histological classification separates dysgerminomas (pure dysgerminomas) from non-dysgerminomatous tumours (mainly: yolk sac tumours, teratomas, embryonal carcinomas, choriocarcinomas). Each histological type of tumour may have specific clinical, biological and/or therapeutic features that it is important to be aware of.

The histological classification includes benign tumours (mature teratomas), benign tumours transformed into malignant tumours (mature cancerised teratomas) and primary malignant tumours. It separates dysgerminomas (pure dysgerminomas) from non-dysgerminomatous tumours (endodermal sinus tumours (or yolk sac tumours), embryonal carcinomas, teratomas (mature and immature), mixed germ cell tumours, choriocarcinomas). This distinction is also important from a clinical and therapeutic point of view.

The International Federation of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (FIGO) [3] staging defined for ovarian adenocarcinomas applies to non-epithelial tumours of the ovary. The vast majority of malignant germ cell tumours are discovered at a localised stage (stage I). In exceptional cases, the diagnosis is made at stage II, in 20-30% of cases at stage III and in less than 10% of cases at stage IV (pulmonary or hepatic metastases are the most frequent). Ascites is detected in only 20% of patients. The size of the tumour probably explains the frequency of tumour rupture before surgery (20% of cases) [4].

In 80-90% of cases, the disease is revealed by abdominal or pelvic pain, which reveals a mass that is already palpable. Other symptoms include: an acute abdominal syndrome that may suggest appendicitis (linked to rupture, haemorrhage or torsion of the tumour), enlargement of the abdomen, metrorrhagia, precocious pseudo-puberty (linked to the secretion of hCG) and, exceptionally, androgenic manifestations. A number of these tumours are discovered during pregnancy (particularly dysgerminomas) or in the immediate post-partum period. Pure dysgerminomas are often slow-growing and the onset of symptoms is sometimes difficult to pinpoint. Less often, the mass is asymptomatic and discovered by chance during a gynaecological examination or an ultrasound scan carried out for another indication.

Abdomino-pelvic ultrasound is an important examination. It enables the characteristics of the tumour (volume, solid-liquid or solid appearance) to be determined more precisely, a peritoneal effusion to be sought, and the contralateral ovary, uterus and liver to be explored. The lymph node areas are best explored by abdomino-pelvic CT scan (this is especially important when there is a dysgerminomatous component). Chest X-rays are part of the routine work-up, possibly supplemented by a systematic chest CT scan, depending on the histological type of tumour. The role of magnetic resonance imaging and PET scanning in these pathologies remains to be defined. One or more tumour markers may be expressed by these tumours. Blood tests should therefore be carried out systematically and, if possible, pre-operatively and as soon as possible after surgery.

Choriocarcinomas produce HCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) and beta-HCG, and endodermal sinus tumours alphafetoprotein. Elevation of one or both of these markers may also be observed in cases of embryonal carcinoma or mixed germ cell tumours. In the vast majority of cases, immature teratomas do not secrete any tumour marker (with the exception of a few described cases of alphafetoprotein production). There is no specific tumour marker for dysgerminomas. In rare cases, elevations of HCG have been reported. On the other hand, elevated levels of LDH (lactic dehydrogenase hormone) have been described in this condition. In the event of initial elevation, LDH levels, which reflect tumour volume, can help to monitor patients undergoing treatment [5]. Tumour markers measured prior to the initial operation can help guide the diagnosis. The results of these assays may also have an impact on treatment after surgery. Finally, the course of the disease (during treatment and at subsequent monitoring) is best followed using the markers initially measured.

The prognosis for germ cell tumours of the ovary has been transformed, firstly by the introduction of chemotherapy and then by the new cisplatin-based chemotherapy protocols. The aim of treatment is fourfold: to cure patients while preserving ovarian hormonal function and fertility, and minimising the toxicity of treatments.

Unlike ovarian adenocarcinomas, surgery for germ cell tumours is conservative in the vast majority of cases. The prognosis is generally excellent for these young patients, for whom the aim is to preserve fertility. As with adenocarcinomas, the aim of surgery is threefold: therapeutic (removal of the tumour), diagnostic (determination of the histological type of tumour) and to help determine the stage of extension. The procedure therefore consists at the very least of a unilateral adnexectomy, complete exploration of the pelvis and the entire abdominal cavity, peritoneal lavage and/or removal of any ascites present when the abdomen is opened, systematic peritoneal biopsies (including of the omentum) and removal of any suspicious elements. In the rare cases where bilateral adnexectomy is indicated, it is recommended that the uterus be preserved (for subsequent oocyte donation).

There is no indication for systematic pelvic and lumbo-aortic lymph node dissection in the absence of lymph node abnormality. Some suggest systematic lymph node sampling, but there are no convincing arguments in the literature for proposing this procedure in the absence of an abnormality.

The aim in these young patients is to preserve ovarian hormonal function and fertility. Systematic bilateral adnexectomy is no longer performed. However, careful inspection of the contralateral ovary is essential. If this ovary is normal, there is no indication for systematic biopsies in the case of non-dysgerminomatous tumours. If an abnormality is found in the contralateral ovary, these areas should be biopsied or excised (lumpectomy if possible). If a teratomatous cyst is found on the contralateral ovary, cystectomy should be performed. On the other hand, bilateral adnexectomy is indicated if gonadal dysgenesis is discovered preoperatively or intraoperatively.

Until recently, tumour reduction surgery was applied to adenocarcinomas, as well as to non-epithelial tumours. Several Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) clinical trials evaluating different chemotherapy protocols have shown differences in survival in favour of patients who have undergone complete tumour reduction, but these differences are not always significant [6-8].

Radiotherapy has long been the standard treatment for ovarian dysgerminomas, which are highly radiosensitive, as are testicular seminomas. Most teams recommended prophylactic irradiation of the homolateral iliac chains or the hemipelvis and para-aortic at a dose of 20 to 30 grays.

The reference protocol is currently BEP. It must be used at effective doses and combines bleomycin (30 units IV or IM per week), etoposide (100 mg/m2/d D1 to 5) and cisplatin (20 mg/m2/d D1 to 5). The BEP protocol is therefore currently the standard protocol for primary malignant germ cell tumours. It is important to start chemotherapy as soon as possible after surgery and to respect the dose intensity of the treatment (respect the three-week interval between courses and avoid ‘untimely’ dose reductions). How patients are monitored depends on the histological type and stage of extension. They are based on clinical examination, marker assays and radiological examinations. There is no reason to suggest a second operation after chemotherapy.

There is no standard protocol for these situations. A distinction is made between platinum-sensitive tumours (relapse occurring more than two months after initial chemotherapy) and platinum-resistant tumours (initial progression or very early relapse).

early relapse). Complete and durable response rates have been observed with protocols containing cisplatin and ifosfamide.

As most of these tumours are unilateral, allowing one ovary to be preserved, hysterectomy is not necessary. Overall, the results in terms of ovarian hormonal function and fertility in patients treated with conservative surgery and chemotherapy are good.

Conclusion

Within germ cell tumors, the diagnostic modalities and therapeutic indications depend on the histological type and the stage of extension of the disease. These are tumors which, most often, have a very good prognosis, provided they are treated using a suitable protocol and without loss of time.

References

- Talerman A. Germ cell tumors of the ovary, in Kurman R (ed): Blaustein's Pathology of the Female Genital Tract (ed 4). Springer-Verlag, New York, 2005; p 849-914.

- Tangir J, Zelterman D, Ma W, et al. Reproductive function after conservative surgery and chemotherapy for malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary. Obstet Gynecol, 2003; 101: 251-257.

- International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Change in definitions of clinical staging for carcinoma of the cervix and ovary. Am J Obstet Gynecol, 2010; 156: 236.

- Herrin VE, Thigpen JT. Germ cell Tumors of Ovary. In: D. Raghavan, ML Brecher, DH Johnson, NJ Meropol, PL Moots, JT Thigpen, ed. in Textbook of uncommon cancer, 2000.

- Williams SD, Gershenson DM, Horowitz CJ, et al. Ovarian Germ-cell Tumors. In Principles and practice of Gynecologic Oncology, Hoskins WJ, Perez CA and Young RC, Lippincott-Raven ed, Philadelphia New-York, Traitement des tumeurs germinales de l'ovaire, 2009; 495: p 987-1001.

- Slayton RE, Park RC, Silverberg SG, et al. (2005) Vincristine, dactinomycin and cyclophosphamide in the treatment of malignant germ cell tumors of the ovary. A Gynecologic Oncology Group study (a final report). Cancer 56: 243-8

- Williams SD, Blessing JA, Moore DH et al. (1989) Cisplatin, Vin-blastine and Bleomycin in advanced and recurrent ovarian germ cell tumors. A trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Ann Intern Med 111: 2

- Williams SD, Kauderer J, Burnett AF, et al. Adjuvant therapy of completely resected dysgerminoma with carboplatin and etoposide: a trial of the Gynecologic Oncology Group. Gynecol Oncol, 2004; 95: 496-499.

- Pautier P, et al. Lhommé Traitement des tumeurs germinales de l'ovaire.