Brivaracetam Induced Ataxia

Honey Desai1,* and Dr. Bhavin Vyas2

1Pharm D 6th year student, Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy practice, Maliba Pharmacy College, Uka Tarsadia University, Bardoli, Gujarat, India

2Associate Professor, Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy practice, Maliba Pharmacy College, Uka Tarsadia University, Bardoli, Gujarat, India

Received Date: 07/01/2025; Published Date: 10/02/2025

*Corresponding author: Honey Desai, Pharm D 6th year student, Department of Pharmacology and Pharmacy practice, Maliba Pharmacy College, Uka Tarsadia University, Bardoli, Gujarat, India

Abstract

Brivaracetam is a relatively new Antiepileptic Drug (AED) increasingly prescribed for the treatment of partial-onset seizures and is highly effective in patients experiencing secondarily generalized tonic–clonic seizures. We report a 66-year-old female with a history of refractory epilepsy, presented with symptoms of unsteadiness and difficulty in coordination after 3 months of receiving brivaracetam 50mg BD. Despite its efficacy and generally favorable side effect profile, there have been reports of neurological adverse effects, including ataxia which is not a commonly reported adverse effect of brivaracetam. This case report adds to the literature on brivaracetam's potential side effects and highlights the importance of considering ataxia as a possible adverse effect, particularly in patients experiencing gait difficulties after starting brivaracetam. The potential mechanisms of brivaracetam-induced ataxia are discussed, along with the management strategies for this adverse effect.

Keywords: BRV-Brivaracetam; AED- Antiepileptic Drugs; SV2A- Synaptic Vesicle protein 2A; ADR- Adverse Drug Reaction; DIMD- Drug Induced Movement Disorders; CTD- Connective Tissue Disease; MRI- Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Introduction

Epilepsy affects more than 50 million people worldwide [1,2]. Over 20 antiepileptic drugs are available for the treatment of epilepsy, and are approved for the treatment of several different types of seizure or syndrome. However, about a third of patients do not respond to AED treatment [3].

Brivaracetam (BRV), a member of the racetam class, is a selective high-affinity ligand for synaptic vesicle protein 2A Brivaracetam has been approved as adjunctive therapy and monotherapy [4] for focal (partial-onset) seizures in patients (≥ 4 years of age) with epilepsy in the United States (US), and as adjunctive therapy for focal seizures [5] in patients (≥ 4 years of age) with epilepsy in the European Union (EU). The primary data that supported the adjunctive and monotherapy indications were derived from three phase III, placebo-controlled, double-blind, fixed-dose trials in patients ≥ 16 years of age with focal seizures uncontrolled by one or two (AEDs).

Brivaracetam is a relatively new addition to the AED arsenal, approved by the FDA in 2016 for the treatment of partial-onset seizures, primarily as an adjunctive therapy in adults. The mechanism lies by interacting with a protein called synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A) in the brain [6]. While generally well-tolerated and prescribed in doses between 10mg to 100mg. It can cause some common side effects including drowsiness, fatigue, dizziness, and nausea. Less frequent side effects include psychiatric disturbances, abnormal gait (including ataxia), and problems with coordination. BRV is easy to use, with no titration and little drug–drug interaction. Efficacy is seen on day 1 of oral use in a significant percentage of patients. Intravenous administration in a 2-minute bolus and 15-minute infusion is well tolerated [7].

Pathophysiology of developing Ataxia:

Ataxia is derived from the Greek word for "disorderly." Originally a general term that was applied to a number of different medical disorders of heartbeat, gait, and movement, "ataxia" is now used more specifically to mean the incoordination of movement following damage of the sensory or cerebellar system. displays motor symptoms and signs and signs of staggering gait, imbalance, incoordination, action tremor, slurred speech, trouble swallowing, disequilibrium/dizziness, nystagmus, and double vision, typically caused by cerebellar dysfunction on the basis of genetic, acquired, or degenerative causes [10].

Although these symptoms may originate from the cerebellum, the disease process may also involve neural pathways that are external to the cerebellum. These pathways include intrinsic brainstem nuclei (oculomotor and bulbar dysfunction), spinal long tracts (spasticity, sensory changes), and supratentorial pathways (basal ganglia symptoms, frontal subcortical cognitive/mood change) [10].

Ataxia is a neurological sign characterized by a lack of voluntary coordination of muscle movements. It is caused by damage to the parts of the nervous system that are responsible for coordinating movement. This damage can be caused by (1) genetic disorders such as Friedreich's ataxia and ataxia-telangiectasia (2) Disease conditions such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, brain tumors, vitamin deficiencies (3) Drug related such as anticonvulsants (4) Social habits like smoking, alcohol [9].

The treatment for ataxia depends on the underlying cause. If the ataxia is caused by a treatable condition, such as a vitamin deficiency, treating the underlying condition may improve the ataxia, if it is drug induced the removal of the culprit drug is effective and may benefit the patient [9,10].

Brivaracetam high-affinity ligand for synaptic vesicle 2A (SV2A) with 15- to 30-fold higher affinity than levetiracetam, the first AED acting on SV2A. It has high lipid solubility and rapid brain penetration, with engagement of the target molecule, SV2A, within minutes of administration. This protein plays a role in regulating the release of neurotransmitters, especially excitatory ones like glutamate. Its effect on SV2A not only suppress seizure activity but also unintentionally affect the release of neurotransmitters involved in balance and coordination, this might have unintended consequences in specific brain regions like the cerebellum or brainstem, leading to imbalances in neuronal activity that affect coordination [8].

Clinical Report

A 66-year-old female patient was admitted to a tertiary care hospital with complaints of being unable to move correctly, with impaired balance and coordination when moving three steps for 1 day which suggests of ataxia. She had a significant medical history of Hypertension (since 2years), Epilepsy (since 1year), Connective Tissue Disease (4-5 months) and medication history of Tab Brivaracetam 50 mg B.D (3 months), Tab Atenolol 25mg O.D, Tab Atorvastatin (10mg) + Aspirin (75mg) H.S.

Investigations:

Her MRI showed left grade 2 mild CTS with, CSF sugar 49 (50-80mg/dl) which suggests of Myoclonic seizure and ataxia. Her Antinuclear Antibody test showed 4 positive and Total protein was <10 (12-60mg/dl) which confirms her suffering from CTD. The patient’s CBC report suggests decreased hemoglobin (11 g/dL), elevated Vitamin B12 >2000 (180-912 Pg/ml), decreased HCT (33.1%), MCV 72.7fl, MCH (24.2 Pg) and high ESR (17 mm).

Differential Diagnosis:

- Sjögren's Syndrome

Sjögren’s syndrome is an autoimmune disorder characterized by dry eyes (keratoconjunctivitis sicca) and dry mouth (xerostomia). It can manifest as primary Sjögren’s syndrome, occurring independently, or secondary Sjögren’s syndrome, associated with other autoimmune diseases. Understanding its distinctions is crucial for effective diagnosis and management [11,12].

Primary Sjögren’s syndrome (PSS) is characterized by the presence of keratoconjunctivitis sicca (dry eyes) and xerostomia (dry mouth) without any associated autoimmune disease. In contrast, secondary Sjögren’s syndrome occurs in conjunction with other connective tissue diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and others. Essentially, the key difference lies in the presence of an underlying autoimmune condition in secondary Sjögren’s syndrome, while primary Sjögren’s syndrome occurs independently.

- Paraneoplastic Cerebellar Degeneration [PCD]

A neurological condition characterized by the progressive degeneration of cerebellar neurons, primarily Purkinje cells, leading to ataxia, tremors, and other neurological symptoms. The immune system mistakenly attacks cerebellar neurons due to cross-reactivity with cancer antigens. This leads to neurological symptoms like ataxia and tremors. Onconeural antibodies are associated with PCD [14].

Treatment:

The patient’s pharmacological strategies include Tab Prednisone 50mg TDS (10 days) f/b 40mg BD (5days), 20mg OD (2days), Tab Mycophenolate Mofetil 360mg BD, Tab Hydroxychloroquine 200mg BD, Tab Syndopa BD, Inj. Omeprazole 40mg OD, Inj. Ondansetron 8mg TDS, Syrup Cremaffin 30ml H.S. Tab Vitamin D3/ calcium carbonate 500mg OD.

Discussion

Brivaracetam-induced ataxia is a relatively rare but noteworthy adverse effect of the drug, primarily used as an antiepileptic medication. The exact incidence of ataxia caused by Brivaracetam remains underreported, partly due to its novelty and limited data. However, recent studies since 2022 provide some insight into its occurrence in clinical practice. Epidemiologically, while the data remains sparse, it is becoming increasingly clear that the risk factors for Brivaracetam-induced ataxia include polypharmacy, advanced age, and a history of neurological conditions. Ongoing research is crucial to better understand the prevalence and risk factors associated with this adverse effect, as this will guide clinicians in making informed treatment decision [15].

Patients with a past medical history of cerebellar disease or epileptic syndromes with history of movement disorders may be at risk of developing some form of ataxia during use of Brivaracetam. They can also alter patient’s sensitivity to the side effects of the medication administered to them. Polypharmacy increases the risk of the outcome as may lead to drug-drug interactions that may exacerbate neurologic manifestations. This is especially the case particularly if other antiepileptic drug or other central nervous system depressants are administered together with the drug. In addition, certain gene profiles of individuals might be more vulnerable to ataxia when administered to brivaracetam especially if the mutations affect cerebellar function [16].

The patient was on Tab Levetiracetam 500mg OD for 9 months and then was shifted to Tab Brivaracetam 50mg BD due to recurrent seizure episodes. The patient presented with signs of ataxia, including unsteady gait, difficulty coordinating movements, and dizziness, which developed after the initiation of Brivaracetam therapy for epilepsy. Given the complexity of her symptoms, a comprehensive diagnostic workup was performed to identify the underlying cause.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) revealed a left grade 2 mild cerebellar tonsillar ectopia (CTS), indicating mild structural abnormalities potentially contributing to her ataxia. Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) analysis showed a slightly low sugar level (49 mg/dL) and findings suggestive of myoclonic seizure, both of which are associated with her neurological presentation.

Further laboratory tests indicated connective tissue disease (CTD), as confirmed by positive Antinuclear Antibody (ANA) test and low total protein levels (<10 mg/dL). This constellation of findings, including the temporal relationship with Brivaracetam initiation, strongly suggests Brivaracetam as the cause of ataxia, necessitating careful consideration of medication adjustment or discontinuation.

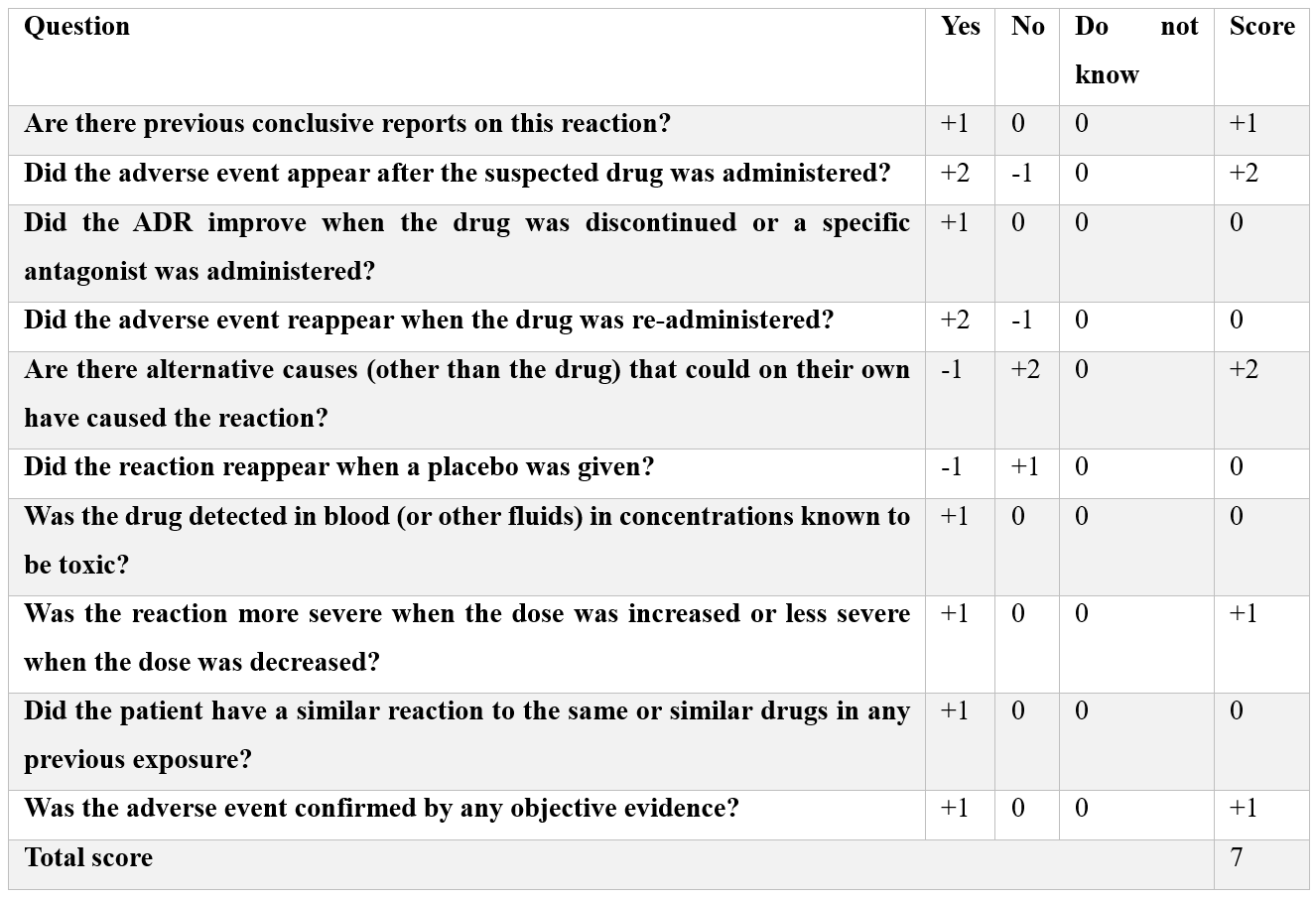

The ADR was neither predictable nor preventable due to its rarity. No De-challenge or Re-challenge was performed and the WHO causality assessment tool gave possible causality term. The Naranjo Scale gave a score of 7 i.e. Probable (Table 1). The Hartwig’s Severity Assessment Scale showed Level 4(b) of severity that is the ADR was the reason for hospitalization.

The severity of the ataxia in the context of CTD, along with the rare presentation of myoclonic seizures, adds a novel dimension to the existing literature. Ataxia is a known side effect of several Anti-Epileptic Drugs (AEDs), including phenytoin, carbamazepine, and valproate, with varying incidences depending on the drug’s mechanism of action and patient-specific factors. Brivaracetam, like levetiracetam, binds to synaptic vesicle protein 2A (SV2A), but its higher affinity might increase the risk of disrupting cerebellar function, leading to ataxia. Compared to older AEDs like phenytoin, which causes ataxia through dose-dependent sodium channel blockade, Brivaracetam’s specific targeting may make it particularly prone to this side effect, especially in patients with pre-existing neurological vulnerabilities [17].

Table 1: Naranjo Scale.

Patient was continued with tapering the dose of Tab Brivaracetam to 25mg BD to balance seizure control and minimize side effects. Symptomatic treatment for ataxia, such as physical therapy or balance training was performed and regular monitored and educated on recognizing symptoms early effective management. Pre-existing neurological illnesses such as cerebellar disorders or epileptic syndromes with a history of movement difficulties can put patients at risk for developing ataxia while taking Brivaracetam. These conditions can also make patients more sensitive to the side effects of the medication. Polypharmacy raises the risk since it may lead to drug interactions that worsen neurological symptoms. This is especially true when other antiepileptic medications or central nervous system depressants are used concurrently. Furthermore, some genetic predispositions, such as mutations impacting cerebellar function, may further raise the risk of ataxia when using brivaracetam.

The specific circumstances surrounding each patient limit the ability of single case reports, like this one, to generalize conclusions. Because individual variability-including underlying medical conditions, hereditary variables, and concurrent drug use—can affect the results, the reported outcomes might not apply to the larger population. Furthermore, there is a chance that confounding variables will mask the actual connection between brivaracetam and the onset of ataxia. These drawbacks highlight the necessity of more extensive research or case studies in order to confirm the conclusions and create more trustworthy clinical recommendations.

Conclusion

The current studies provide few insights on the prevalence of Brivaracetam-induced ataxia, and the epidemiology of this condition is not well-documented. While ataxia is an uncommon but clinically important adverse drug response (ADR), this case report clarifies that brivaracetam is typically regarded as safe and well-tolerated. Brivaracetam may cause less ataxia than earlier antiepileptic medications, but it is still a worry, especially for individuals who already have neurological disorders, are undertaking polypharmacy, or have specific genetic predispositions. To precisely identify the incidence, underlying processes, and particular risk factors linked to Brivaracetam-induced ataxia, more study is necessary. Enormous research and information from pharmacovigilance initiatives may be crucial in pinpointing high-risk populations and enhancing patient outcomes. By underlining the necessity of individualized patient care techniques, our case report adds important details to the body of knowledge already available on the safety profile of brivaracetam.

References

- von Rosenstiel P. Brivaracetam (ucb 34714). Neurotherapeutics, 2007; 4(1): 84-87.

- Klein P, Diaz A, Gasalla T, Whitesides J. A review of the pharmacology and clinical efficacy of brivaracetam. Clinical pharmacology: advances and applications, 2018: 1-22.

- Brandt C, Klein P, Badalamenti V, Gasalla T, Whitesides J. Safety and tolerability of adjunctive brivaracetam in epilepsy: in-depth pooled analysis. Epilepsy & Behavior, 2020; 103: 106864.

- Hannah JA, Brodie MJ. Treatment of seizures in patients with learning disabilities. Pharmacology & therapeutics, 1998; 78(1): 1-8.

- Waites AB, Abbott DF, Fleming SW, Jackson GD. Magnetic resonance neurophysiology: Simultaneous EEG and fMRI. Magnetic Resonance in Epilepsy, 2005: 299-314.

- Rolan P, Sargentini‐Maier ML, Pigeolet E, Stockis A. The pharmacokinetics, CNS pharmacodynamics and adverse event profile of brivaracetam after multiple increasing oral doses in healthy men. British journal of clinical pharmacology, 2008; 66(1): 71-75.

- Klein P, Bourikas D. Narrative Review of Brivaracetam: Preclinical Profile and Clinical Benefits in the Treatment of Patients with Epilepsy. Advances in Therapy, 2024: 1-8.

- Oster JM. Brivaracetam: A newly approved medication for epilepsy. Future Neurology, 2019; 14(3): FNL23.

- Manto M, Serrao M, Castiglia SF, Timmann D, Tzvi-Minker E, Pan MK, et al. Neurophysiology of cerebellar ataxias and gait disorders. Clinical Neurophysiology Practice, 2023.

- Perlman SL. Update on the treatment of ataxia: medication and emerging therapies. Neurotherapeutics, 2020; 17(4): 1660-1664.

- Bloch KJ, Buchanan WW, Wohl MJ, Bunim JJ. Sjögren's syndrome: A Clinical, Pathological, and Serological Study of Sixty-two Cases. Medicine, 1965; 44(3): p 187-231.

- Ferro F, Vagelli RO, Bruni C, Cafaro G, Marcucci E, Bartoloni E, et al. One year in review 2016: Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Exp Rheumatol, 2016; 34(2): 161-171.

- Rohatgi S, Nimal S, Nirhale S, Rao P, Naphade P, Dubey P, et al. Atypical Presentation of Seronegative Paraneoplastic Lambert–Eaton Myasthenic Syndrome with Cerebellar Ataxia. Annals of Indian Academy of Neurology, 2024; 27(3): 319-321.

- Vernino S. Paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration. Handbook of clinical neurology, 2012; 103: 215-223.

- Siddiqui F, Soomro BA, Badshah M, Rehman EU, Numan A, Ikram A, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Brivaracetam in Persons with Epilepsy in a Real-World Setting: A Prospective, Non-Interventional Study. Cureus, 2023; 15(12).

- Klein P, Diaz A, Gasalla T, Whitesides J. A review of the pharmacology and clinical efficacy of brivaracetam. Clinical pharmacology: advances and applications, 2018: 1-22.

- Steinhoff BJ, Staack AM. Levetiracetam and brivaracetam: a review of evidence from clinical trials and clinical experience. Therapeutic Advances in Neurological Disorders, 2019; 12: 1756286419873518.