Benign Biliary Strictures (BBS) Mimicking a Cholangicoracinoma

Touimi KB, El Mkhalet M*, Elwassi A, Hajri A, Erguibi D, Boufettal R, Jai SR and Chehab F

Department of General Surgery 3 University Hospital Ibn Rochd, Casablanca, Morocco

University of Medicine and Pharmacy Hassan II Casablanca, Morocco

Received Date: 29/12/2024; Published Date: 06/02/2025

*Corresponding author: El Mkhalet M, Department of General Surgery 3 University Hospital Ibn Rochd, Casablanca, Morocco; University of Medicine and Pharmacy Hassan II Casablanca, Morocco

Abstract

This case report discusses a 57-year-old female patient with a medical history of thyroid cyst surgery 28 years ago, presenting with right upper quadrant pain and clinical cholestasis syndrome. Abdominal ultrasound showed microlithiasis in the gallbladder and dilatation of the Common Bile Duct (CBD), Intrahepatic Bile Ducts (IHBD), and the Wirsung duct. A biliary MRI suggested a tumoral process in the common bile duct just below the lower biliary confluence, associated with upstream ductal dilation and pancreatic atrophy. This case highlights the complex diagnostic challenge and clinical progression of biliary tract pathology in a middle-aged patient with a prior history of thyroid surgery.

Introduction

Bile duct stricture is a fixed narrowing of a focal segment of the bile duct that results in proximal biliary dilatation and clinical features of obstructive jaundice [1] it is challenging to manage. Most benign strictures are related to surgical procedures, following bile duct injury after liver transplantation and laparoscopic cholecystectomy, with reported incidences varying from 3% to 13% [2]. The diagnosis of biliary stricture is often missed or delayed because of its indolent course, with up to 20% of patients presenting with subtle clinical manifestations 1 year after the initial injury [3].

This case report details a patient who presented with cholestasis syndrome. The report will also outline the management approach and review the relevant literature.

Case Report

A 57-year-old female patient, who underwent thyroid cyst surgery 28 years ago. Her medical history dates back one month, when she developed right upper quadrant pain associated with a clinical cholestasis syndrome, without other significant clinical signs. This condition progressed in the context of fever lessness, asthenia, anorexia, and unquantified weight loss. Upon admission, the patient was conscious and stable in terms of her hemodynamic status and respiratory status. She presented with generalized jaundice of the skin and mucous membranes.

Abdominal examination revealed no surgical scar, but tenderness in the right upper quadrant; the rest of the abdomen was soft, with no palpable masses. There was no hepatomegaly or splenomegaly. A pelvic exam showed no particular findings.

On cervical examination, a low cervical incision scar was observed, with no palpable masses. The remainder of the clinical exam was unremarkable.

Abdominal Ultrasound: Presence of microlithiasis in the gallbladder. Dilatation of the common bile duct (CBD), unspecified degree, as well as intrahepatic bile ducts (IHBD) and the Wirsung duct, measuring 5mm in diameter.

Biliary MRI: Suggestive of a tumoral process in the common bile duct just below the lower biliary confluence, with upstream ductal dilation, Pancreatic atrophy. Small lymph node at the left renal hilum. Chronic pyelonephritis in the right kidney (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Ductal dilatation.

Tumor Markers:

- ACE: 3.38 ng/ml

- CA 19-9: 33.90 U/ml

Pre-anesthesia Assessment:

- Complete Blood Count (CBC): Hb - normal; WBC - normal.

- Liver Function Tests:

- ALP/GGT: 145/43 U/L

- Total Bilirubin (TB)/Direct Bilirubin (DB): 56/43 mg/L

- AST/ALT: 35/28 U/L

- BL: 13.4 mg/L

- Renal Function:

- Urea/Creatinine: 0.40 g/L / 8.2 mg/L

- Coagulation Profile:

- Prothrombin Time (PT): 101%

- Quick (Q): 12.3 sec

- TCA (Activated Partial Thromboplastin Time): 28/29 sec

- Fibrinogen: 3.76 g/L

- Electrolyte Panel:

- Na: 141 mEq/L

- K: 4.2 mEq/L

- Albumin: 34 g/L

- ECG and Chest X-ray: Normal.

- Blood Type: A+

The Surgical Procedure was Resection of a segment of the common bile duct, Retrograde cholecystectomy. Hepaticojejunostomy: Y-shaped Roux-en-Y anastomosis. Drainage: Pre- and retro-anastomotic drainage with 2 Delbet blades Subhepatic drainage: Salem tube placed.

During the procedure, an intraoperative examination of the ascitic fluid, gallbladder and lymph node dissection was performed, which revealed inflammatory changes with no sign of malignancy, and according to the additional pathological report: chronic and nonspecific inflammatory and fibrotic changes of the common bile duct, nonspecific chronic cholecystis with no evident signs of specificity or malignancy.

Discussion

Definition and classification

BBSs most often arise from postoperative or inflammatory etiologies. Surgery-related BBS most frequently results from LC, bile-duct surgery, and liver transplantation. The incidence of LC-related BS is ~0.5%, usually caused by direct surgical bile-duct injury, including thermal injury, scissors, ligatures, or clips [4].

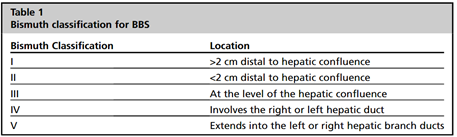

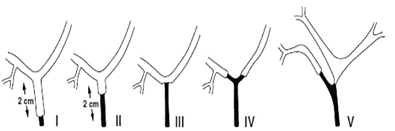

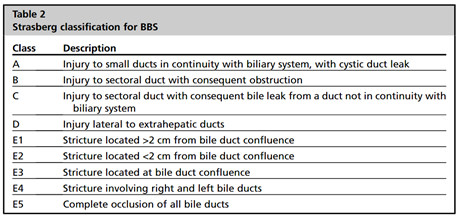

There are 2 main classification systems used to evaluate biliary duct strictures. The Bismuth classification, which is most commonly used, is based on stricture location (Table 1). The Strasberg classification (Table 2) describes the anatomy and characteristics of the stricture [5].

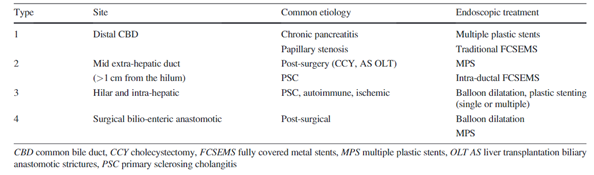

Many if not most BBS are not post-surgical and the classification is rarely used in deciding etiology or management strategy for the endoscopist. Hence, a new classification is needed to help diagnose and manage these strictures : The new classification [6].

Taking a careful clinical history may help to elucidate the etiology of a biliary stricture. Malignant etiology should be suspected if a patient does not have one of the more common reasons to develop a benign biliary stricture, such as history of biliary surgery, liver transplantation, cholelithiasis, pancreatitis, or cholangitis [7].

BBS have diverse causes, each with different natural histories and management strategies, most of which incorporate the use of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP): [5].

Postoperative strictures

- CCY: open or laparoscopic

- Orthotopic liver transplant: deceased donor and living related donor transplants

- Biliary-enteric anastomosis: hepaticojejunostomy, choledochojejunostomy, and pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple procedure)

- ERCP: biliary sphincterotomy, dilation, and stenting

- Percutaneous therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma: transcatheter arterial chemoembolization, radiofrequency ablation, percutaneous ethanol injection

- Radiation therapy

Traumatic

- Choledocholithiasis

- Pancreatolithiasis

- Mirizzi syndrome

- Physical injury: motorized vehicle accident, blunt abdominal trauma

Ischemic

- Hypotension

- Hepatic artery thrombosis or stenosis

- Prolonged transplant organ ischemia: warm and cold ischemic times

- Portal biliopathy

Inflammatory

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Primary sclerosing cholangitis

- Autoimmune cholangiopathy (immunoglobulin G4–associated cholangiopathy)

- Vasculitis: systemic lupus erythematosus, antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody –associated vasculitis, Behc ̧et disease

Infectious

- Recurrent pyogenic cholangitis

- Parasitosis: Ascaris lumbricoides, Clonorchis sinensis, and Opisthorchis viverrini

- Granulomatous: tuberculosis, histoplasmosis

- Viral: cytomegalovirus, human immunodeficiency virus

Abbreviations: I3, Ischemic, Inflammatory and Infectious; PO, Postoperative strictures; T, Traumatic

Clinical Presentation

The diagnosis of biliary stricture is often missed or delayed because of its indolent course, with up to 20% of patients presenting with subtle clinical manifestations 1 year after the initial injury. Up to 30% of patients with nonmalignant strictures may have a protracted, complicated course necessitating intensive multidisciplinary management with its attendant significant health care costs [8]. Clinically, benign biliary stricture can present with a wide array of manifestations, ranging from being completely asymptomatic to showing overt clinical and laboratory evidence of biliary obstruction. Clinical manifestation may also depend on the underlying cause of biliary stricture and its location. Typically, the symptoms are related to obstructive jaundice with elevated levels of bilirubin and liver enzymes (alkaline phosphatase and γglutamyl transferase) with or without cholangitis. Chronic low-grade biliary obstruction can lead to recurrent cholangitis, stone formation, and even cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease [8].

Diagnostic Approach

Biliary strictures are usually accompanied by upstream ductal dilatation. Ultrasound is a sensitive tool for detecting intrahepatic biliary ductal dilatation and is thus generally the first choice screening exam for the evaluation of biliary obstruction. While the accuracy of ultrasound in the detection of biliary dilatation is greater than 90%, its accuracy in the detection of the underlying cause is lower, varying from 30 to 70% [30].

Multiphase contrast-enhanced CT can be useful for this purpose. The typical imaging clues which help delineate malignant strictures on CT include biliary hyperenhancement, wall thickness greater than 1.5 mm, irregular asymmetric wall thickening with shouldered margins, and long segment strictures. Conversely benign lesions tend to demonstrate smooth, regular, short-segmental narrowing.31 CT also provides the benefit of detecting metastatic lesions in the case of malignancy as well as detecting the underlying cause of obstruction and any associated complications.

MRCP is a highly accurate imaging modality that has been widely adopted in the evaluation of biliary obstruction, with a reported diagnostic sensitivity of up to 98%. However, the sensitivity of MRCP for the differentiation of benign from malignant strictures is weaker, ranging from 30 to 98%. Importantly, MRCP is especially useful and often diagnostic in the evaluation of PSC, iatrogenic bowel injuries, and anastomotic strictures without the need for direct tissue sampling.

Another valuable imaging modality is endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) with or without endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP), which has demonstrated up to 97% sensitivity and 88% specificity in differentiating benign from malignant strictures. EUS provides the added benefit of allowing for tissue sampling with cytologic brushings or fine needle aspiration; further interventions including balloon angioplasty or stent insertion can also be performed concomitantly.

Intraductal Endoscopic Ultrasound (IDUS) is a newer technique which utilizes a high-frequency, wire-guided ultrasound probe that is inserted into the extrahepatic bile ducts during ERCP. IDUS with ERCP has shown the ability to diagnose biliary strictures caused by malignant tumors which were not visible on CT. ERCP/IDUS may have superior diagnostic accuracy than MDCT or EUS alone. The drawback of ERCP with IDUS/EUS is its requirement for an invasive endoscopic procedure with risks such as biliary or bowel perforation [9].

Biopsy and cytology of bile ducts and bile samples, as well as a frozen section diagnosis of the marginal bile duct from a malignancy, are the depressed pathological specimens for general pathologists. In addition, the pathological diagnosis is also possibly influenced by the radiological findings and the clinical diagnosis [10].

Treatment Options

There is no agreed standardised management for BBS but endoscopic management is preferred to surgical management in the first instance, Endoscopically BBS are typically managed by ERCP with sphincterotomy, balloon dilatation (BD) and/or stent placement [11].

Prophylactic administration of intravenous antibiotics covering the Gram-negative bacteria Enterococcus and Pseudomonas are recommended for patients with hilar strictures, liver transplantation, and PSC, due to the potential for complex or multiple strictures complicating these conditions [4].

Surgical drainage is the definitive therapy for BBS with high long-term success rates, although surgical morbidity can be substantial[12] Surgical approaches differ case by case, but include; repair of the biliary anastomosis, conversion of a duct to duct anastomosis to an hepaticojejunostomy or ultimately retransplantation [11]. Cholangiojejunostomy is the most widely used surgical procedure for biliary stricture caused by various abnormalities. However, postoperative complications of this surgery are gradually highlighted with its extensive clinical application, especially complications of reflux cholangitis, anastomotic stoma stricture and intrahepatic lithiasis [13].

Percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) is usually reserved for long complex strictures or disconnected bile ducts that cannot be traversed by an ERCP approach or patients who have undergone Roux-en-Y reconstruction [11].

Treatment of recurrent BBS is similar to the management of primary BBS, however given the recent adoption of FCSEMS as a primary modality for BBS management, consideration can be made to treating patients with a FCSEMS or giving the patient a longer than previous trial with multiple plastic stents before considering referral for surgical biliary reconstruction [11].

Novel techniques, including magnetic compression anastomosis, intraductal radiofrequency ablation, and biodegradable stents, may be useful for selected BBS cases refractory to endoscopic or percutaneous methods [4].

Conclusion

Benign biliary strictures (BBS) are rarely encountered in the general population and require coordinated care between medical, surgical, pathologic, and radiologic specialties for appropriate evaluation and management.

References

- Katabathina VS, Dasyam AK, Dasyam N, Hosseinzadeh K. Adult Bile Duct Strictures: Role of MR Imaging and MR Cholangiopancreatography in Characterization. RadioGraphics, 2014; 34(no 3): p. 565‑ doi: 10.1148/rg.343125211.

- Wong JYJ, Conroy M, Farkas N. Systematic review of Meckel’s diverticulum in pregnancy. ANZ J. Surg., 2021; 91(no 9). doi: 10.1111/ans.17014.

- Dadhwal US, Kumar V. Benign bile duct strictures. J. Armed Forces India, 2012; 68(no 3): p. 299‑303. doi: 10.1016/j.mjafi.2012.04.014.

- Ma MX, Jayasekeran V, Chong AK. Benign biliary strictures: prevalence, impact, and management strategies. Exp. Gastroenterol., 2019; 12: p. 83‑92. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S165016.

- Baron TH, DaVee T. Endoscopic Management of Benign Bile Duct Strictures. Endosc. Clin. N. Am., 2013; 23(no 2): p. 295‑311. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2013.01.001.

- Kaffes AJ. Management of benign biliary strictures: current status and perspective. Hepato-Biliary-Pancreat. Sci., 2015; 22(no 9): p. 657‑663. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.272.

- Fidelman N. Benign Biliary Strictures: Diagnostic Evaluation and Approaches to Percutaneous Treatment, Vasc. Interv. Radiol., 2015; 18(no 4): p. 210‑217. doi: 10.1053/j.tvir.2015.07.004.

- Shanbhogue AKP, Tirumani SH, Prasad SR, Fasih N, McInnes M. Benign Biliary Strictures: A Current Comprehensive Clinical and Imaging Review, J. Roentgenol., 2011; 197(no 2): p. W295‑W306. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.6002.

- Altman A, Zangan S. Benign Biliary Strictures. Interv. Radiol., 2016; 33(no 4): p. 297‑306. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1592325.

- Nguyen Canh H, Harada K. Adult bile duct strictures: differentiating benign biliary stenosis from cholangiocarcinoma. Mol. Morphol., 2016; 49(no 4): p. 189‑202. doi: 10.1007/s00795-016-0143-6.

- Keane MG, Devlin J, Harrison P, Masadeh M, Arain MA, Joshi D. Diagnosis and management of benign biliary strictures post liver transplantation in adults. Rev., 2021; 35(no1): p. 100593. doi: 10.1016/j.trre.2020.100593.

- Ramchandani M, Pal P, Costamagna G. Management of Benign Biliary Stricture in Chronic Pancreatitis. Endosc. Clin., 2023; 33(no4): p. 831‑844. doi: 10.1016/j.giec.2023.04.002.

- Shalayiadang P, et al. Long-term postoperative outcomes of Roux-en-Y cholangiojejunostomy in patients with benign biliary stricture. BMC Surg., 2022; 22(no1): p. 231. doi: 10.1186/s12893-022-01622-y.