Stress, Conscientiousness, Neuroticism and Depression among Dental Students

Ahmed Bokhari1,2, Jim E Banta3,*, Leslie R Martin4, Mark Ghamsary1 and John M Banta4

1School of Public Health, Loma Linda University, USA

2College of Dentistry, Jazan University, Saudi Arabia

3School of Public Health, Loma Linda University, USA

4School of Public Health La Sierra University, USA

Received Date: 14/10/2023; Published Date: 20/03/2024

*Corresponding author: Jim E Banta, Loma Linda University School of Public Health, 24851 Circle Dr., Loma Linda, CA 92350, USA

Abstract

Objectives: This study aimed to identify perceived stress levels among dental students, the association between dental school stress and mental health, and the degree to which these associations might be mediated by the personality traits of conscientiousness and neuroticism.

Methods: A sample of dental students at Loma Linda University (n = 318) participated in a cross-sectional study stratified by academic year, using validated self-report measures to assess conscientiousness, neuroticism, perceived stress, and depression. Linear regressions were used to reveal how conscientiousness and neuroticism and their interactions might predict depression in dental students.

Results: The results revealed moderate levels of stress (66.43 ± 17.25, Dental Environmental Stress) and depression (12.05 ± 11.00, Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Revised) in these students with a significant association between them. Neuroticism served as a partial mediator of the relationship. Although conscientiousness was protective, it did not demonstrate a mediational effect. No significant associations between depression and its covariates were observed.

Conclusion: Stressors associated with dental school are risk factors for depression, particularly for students whose personalities (i.e., neuroticism) may predispose them to experiencing greater stress and depression.

Keywords: Stress; Conscientiousness; Neuroticism; Depression; Dental students

Introduction

Stress is one of the most common causes of illness in the U.S. [1] and is a significant contributor to depression, cardiovascular disease, hypertension and infectious disease [2,3]. Measurable increases in stress have been documented in nationally representative samples in the U.S., in 1983, 2006, and 2009 [1]. Workplace stress is common among dentists [4] and contributes to professional burnout and dental errors [5]. Dental procedures require high levels of concentration for extended time periods and very fine hand movements, frequently in awkward postures, all contributing to stress [6]. Dentists must also handle patients, maintain pace with scheduling, and manage their staff and finances [7].

Dental students are prone to the same types of stress as dentists, while also managing academic stressors [8-10]. Beyond general clinical pressure, stressors in dental school can include burdens from large amounts of classwork, patient interactions, and difficulties in learning specific clinical procedures [10]. Dental students often become depressed [11,12] which, in addition to compromising well-being has been linked to negative health outcomes [13]. Many depressed students do not seek help due to denial, ignorance, or stigma [14,15], making this contributor to poor health outcomes challenging to identify [16]. Further, high levels of stress among dental students [17], may contribute, in combination with depression, to decreased performance, which can cause even more stress. Personality traits such as conscientiousness and neuroticism may influence the way stressors are interpreted, and therefore play a role in the stress-depression relationship.

Conscientiousness

Conscientiousness is a collection of personal characteristics such as organization, diligence, and attention to detail [18,19] that has consistently been linked to better job performance across a variety of domains [20,21], including health professions, where it may encourage striving for the highest quality care for patients. Although conscientiousness is typically viewed as a positive quality, excessive conscientiousness is labeled “perfectionism,” and manifests through self-critical appraisal wherein an individual accepts nothing less than his or her best performance [22]. This more extreme form of conscientiousness is clearly not beneficial.

Neuroticism

Neuroticism is another factor that may be particularly relevant to understanding the stress experiences of dental students. Neuroticism is a collection of behaviors including anxiety, unpredictable changes in mood, worrying and emotional negativity [23]. Neurotic people are often more sensitive to the opinions and criticisms of others, and this trait is often accompanied by self-deprecation and low self-esteem [24]. These characteristics can thus affect such individuals’ coping with daily conflicts in life [25]; accordingly, neurotic people tend to experience negative emotions more often [26] and tend to handle job stressors less effectively than do those lower on the dimension [27].

Interaction between conscientiousness and neuroticism

Conscientiousness and neuroticism are both relevant to the experience of stress, and when these two traits interact they may produce different effects. [28] found that combined high levels of conscientiousness and neuroticism synergistically resulted in greater stress than either could create alone. When high conscientiousness is combined with low neuroticism, relatively low degrees of perceived stress are found but high levels of neuroticism may contribute to the development of excessive conscientiousness (i.e., perfectionism) and associated increased stress [29].

Methods

This cross-sectional study measured stress among dental students at Loma Linda University and well as its association with depression. In addition, the degree to which conscientiousness and neuroticism might mediate the relationship was evaluated. Additional details regarding study design are available elsewhere [30].

Measures

To assess stress, the Dental Environmental Stress (DES) questionnaire was used [8,10]. The questionnaire is comprised of 38 questions pertaining to stressors at dental school with responses ranging from 1 = “Not stressful” to 4 = “Very stressful.” Responses were then summed to create the scale score, which has demonstrated good internal consistency reliability [31] with a Cronbach's α = .91.

For the depression assessment, the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Revised (CESD-R) [32] instrument was used. The CESD-R is a 20-item survey with responses scored on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = “Not at all or less than one day” to 4 = “Nearly every day for 2 weeks.” Based on the responses received, we then collapsed the third and fourth responses into a single response, 3 = “5-7 days” or “Nearly every day for 2 weeks.” Scale scores were calculated by summing the 20 items for each trait. The internal consistency test was good with Cronbach’s alpha = .93.

Conscientiousness and neuroticism were each measured using the trait-relevant ten items from the International Personality Item Pool (IPIP), a simple but widely used indicator of the five-factor model of personality [33]. This model has been applied extensively including with students [34], physicians, and various employee types and has been shown to validly assess the dimensions of interest. Each item is presented as a statement and respondents use a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = “very inaccurate” to 5 = “very accurate” to indicate how well each statement describes them as they currently see themselves. Scale scores were calculated by summing the ten items for each trait. The internal consistency and reliability for these measures is good, with Cronbach’s αs of .85 for conscientiousness and .88 for neuroticism [33].

Not only was the degree to which each personality characteristic exists in an individual expected to be an important predictor of depression, the interaction of the two traits was also predicted to be meaningful. Thus, an interaction term was created by multiplying the conscientiousness score by the neuroticism score for each individual. This interaction term was then entered into the regression equation as an additional predictor.

Procedures

After approval by the Loma Linda University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB # 150119), students were recruited via the School of Dentistry’s Students Affairs Office. A mass email was sent to all dental students with a recruitment letter and a flyer that briefly explained the goal of the study and provided instructions for participation. A link to a secure server (Qualtrics) was provided in the email for those who wished to participate online. For those who wished to participate via hard copy, sessions were scheduled for distribution of the questionnaires. No personal identifiers were collected from the online or hard copy surveys to ensure anonymity. Participants who wished to enter a drawing for incentives were given the opportunity to provide their name and contact information separately from their survey responses.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical tests on the variables and their covariates were done using the software package SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp. Released 2013. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographics and main variables. Multiple linear regression analysis was used to examine the value of stress and personality as predictors of depression.

Results

Table 1 presents the demographic characteristics of the sample, as well as summaries of stress, personality, and depression scores. The mean age of the respondents in the study was 27 years, and there were more men than women (57.90% male). The majority of the respondents were in their second through fourth year of the DDS program (84.00%), and Asians comprised more than 41.00% of the sample, followed by Caucasians. As a group, participants indicated moderate levels of stress (66.43 ± 17.25 with a possible range of 38-152); moderate-high levels of conscientiousness (36.88 ± 6.12) and moderate levels of neuroticism (31.19 ± 6.67) each with a possible range of 10-50; and low levels of depression (12.05 ± 11.00 with a possible range of 0-60). None of these variables, with the exception of conscientiousness, had restricted range.

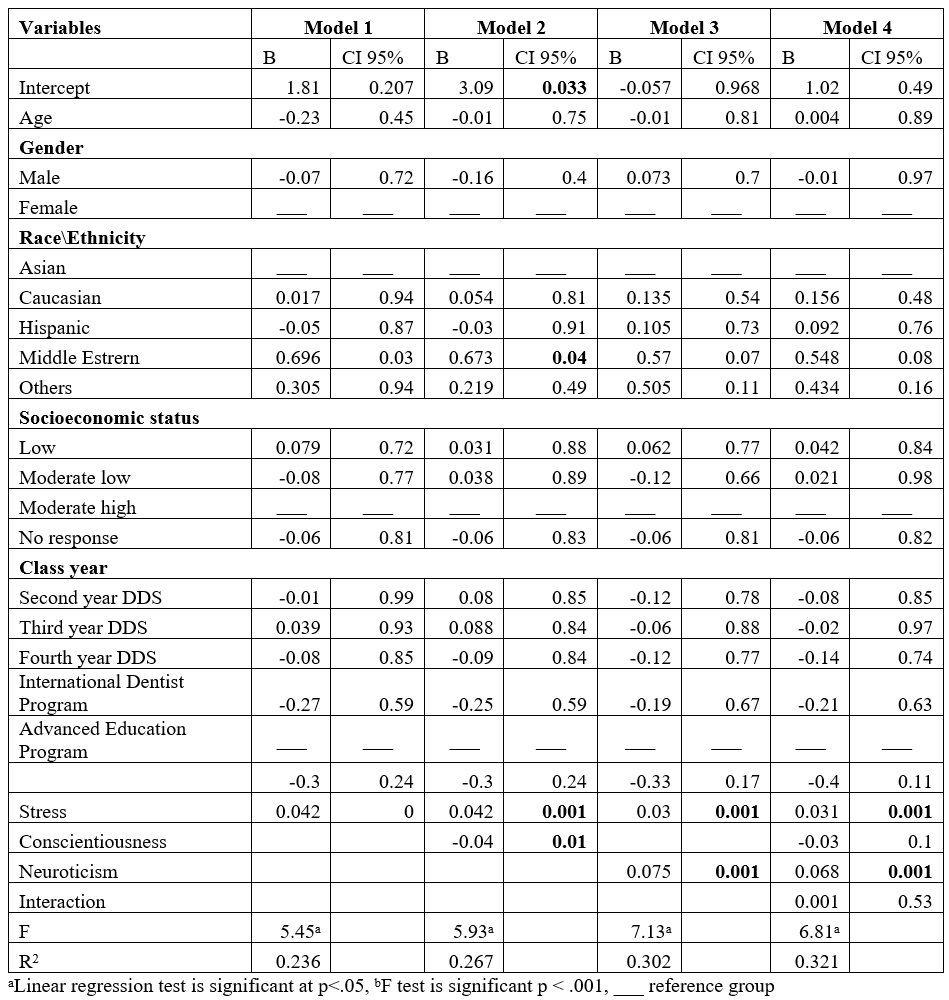

Table 2 presents the associations between depression, stress, conscientiousness, and neuroticism with age, gender, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, class year, and Grade Point Average (GPA) as covariates using linear regression models. In the first model, stress was used to predict depression with the covariates. Stress significantly predicted depression (β = 0.042, p < 0.001, [95% CI 0.031, 0.054]), and this model accounted for 23.60% of the total variance in depression (R2 = 0.236); none of the covariates were significantly related to depression.

In the second model, conscientiousness was added (nothing removed). Conscientiousness was found to be significantly protective against depression (β = -0.043, p = .005 [95% CI -072, 0.013]), with stress remaining significantly associated with depression (β = 0.042, p < .001, [95% CI -0.031, 0.053]) and no evidence of mediation. This model accounted for 26.70% of the variance in depression (R2 = 0.267).

The third model replaced conscientiousness with neuroticism, again leaving all covariates. Neuroticism (β = 0.075, p < .001, [95% CI 0.045, 0.104]) predicted depression and appeared to serve as a partial mediator of the stress to depression link (β = 0.030, p < .001, [95% CI 0.018, 0.042]); this model accounted for 30.20% of the variance in depression (R2 = 0.302). The fourth full multiple linear regression analysis model, with all predictors included and 32.10% of the variance in depression explained (R2 = 0.321), shows a significant association remaining between dental-school stress and depression, with a stress β-coefficient of 0.031 (p < .001, [95% CI 0.019, 0.043]). In this model, the conscientiousness (β = -0.025, p < .095, [95% CI -0.055, 0.004]) association with depression becomes non-significant, while neuroticism (β = 0.068, p < .001, [95% CI -0.037, 0.098]) remains significantly associated with depression. The interaction between conscientiousness and neuroticism, however, does not add significant predictive value to the model, contrary to expectations (β = 0.001, p = .530, [95% CI -0.003, 0.005]). The other covariates, as before, were not significantly associated with depression. Regarding perfectionism, the potential non-linear effect of conscientiousness on depression was tested. It was done by entering a dummy variable for perfectionism which did not have a significant change (β = 0.050 for stress), thus the simpler model (fourth model) was maintained.

Table 1: Demographics and descriptive analysis of levels of stress, conscientiousness, neuroticism and depression among dental students.

Table 2: Linear regression analysis between stress, conscientiousness, neuroticism, interaction of two personality traits and covariates with depression among dental students.

Discussion

An examination of the stress-depression relationship experienced by dental students, in the context of personality traits such as conscientiousness and neuroticism, has not been previously undertaken. Our results, however, were consistent with the findings of other studies regarding the stress experience in dental school [9,10]. As previously noted, the nature of the stress-depression relationship is reciprocal [11] and although we did not specifically test for this, the strong observed association of these two variables lends support to the idea. We also found that conscientiousness was a significant protective factor for depression, which is consistent with previous studies [19,20,35,36], although this protective effect was reduced to non-significance in the full model that included neuroticism. The possibility that extreme levels of conscientiousness (i.e., “perfectionism”) might be detrimental remains, but we had too few students at very extreme levels to be able to identify any such trend (although those students [n=30] who scored 45 or greater out of 50 on the conscientiousness measure did not show a different pattern, their conscientiousness was not significantly related to depression: β = -0.243, p < .359, 95% CI -0.802, 0.316). A more detailed conscientiousness tool may have provided a more nuanced view, and enabled more extensive analysis of this question.

Neuroticism not only predicted depression in its own right, but when it was included in the model, the predictive power of stress to depression was diminished (although it remained significant). This suggests that neuroticism is a partial mediator of the stress-depression association—that is, the tendency to experience negative emotions that defines neuroticism partly explains the association between stress and depression.

Because the interaction between the two traits is unrelated to the stress-depression relationship (β = 0.001, p = .530), we conclude that these traits are likely tied to stress and depression through separate paths with the elements associated with neuroticism (such as anxiety) appearing to be of primary relevance. As such, when resources are limited, it would make most sense to evaluate students’ neuroticism levels when trying to appropriately target stress-reduction interventions.

These findings are important, not because they confirm that dental school is a stressful experience and that this stress predicts depression, but because they provide insight into how we might most effectively intervene to minimize depression. Most dental schools, as part of their university affiliation, provide mental health services to students but it is not clear that any particular outreach or individualized targeting is taking place. Because mental health status, in the form of depression, is predicted by perceived stress, stress assessments may provide an easy early-warning system to identify those who may benefit from some form of assistance. For certain students this may involve a referral for counseling or connection with other resources; for others, simply being aware of the association and taking care to manage life-stresses may be enough. The more important finding from this study, however, is that those high on the neuroticism scale may be particularly at risk and, as such, may warrant earlier or more intensive intervention. Implementing educational and intervention programs that address the issue of mental well-being can assist in preventing depression, as dental students may be particularly prone to depression given their high stress—and this may be especially true for those with higher neuroticism [37]. However, these intervention programs were not used to stigmatize, label or categorize these students. Categorizing students into different levels of neuroticism would violate the justice and beneficent ethical values of the study. Further investigations should include larger samples with more schools and in multiple regions, although the relatively diverse nature of this sample suggests that the results are likely to generalize well.

Some limitations were encountered in this study. Since it is a cross-sectional study, it was not possible to establish a cause-and-effect relationship. Also, limiting the sample from one school could bring into question the generalizability to other dental schools in California or across the nation. Moreover, self-report surveys may tend to biases such as recall bias or response bias. In the other hand, testing the linkage between stress with depression under the influence of conscientiousness and neuroticism, is one of the main strengths of the study. This approach produced novel findings by contrasting stressed-out students and their depression risk levels according to their personalities. The large sample size (n=318) assured adequate power to detect differences. Finally, the diversity of students at Loma Linda University’s dental school enhances the generalizability of results, which hopefully will encourage the generation of additional hypotheses which may lead to improved education at dental schools in Southern California and beyond.

Conclusion

Cutaneous manifestations are infrequent in patients with cardiac myxoma, and they may represent the only symptoms.

Dermatologists should be vigilant about these signs as they can indicate underlying cardiac myxomas and prevent further complications.

References

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D. Who's stressed? Distributions of psychological stress in the United States in probability samples from 1983, 2006, and 2009. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 2012; 42(6): 1320-1334.

- Cohen S, Janicki-Deverts D, Miller GE. Psychological stress and disease. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2007; 298(14): 1685-1687.

- Epel ES, Crosswell AD, Mayer SE, Prather AA, Slavich GM, Puterman E, et al. More than a feeling: A unified view of stress measurement for population science. Frontiers in Neuroendrocrinology, 2018; 48:146-169. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2018.03.001.

- Myers H, Myers L. 'It's difficult being a dentist': stress and health in the general dental practitioner. British Dental Journal, 2004; 197(2): 89-93.

- Yansane A, Tokede O, Walji M, Obadan-Udoh E, Riedy C, White J, et al. Burnout, Engagement, and Dental Errors Among U.S. Dentists. Journal of patient safety, 2021; 17(8): e1050–e1056. https://doi.org/10.1097/PTS.0000000000000673

- Lemaster MF, Kelleran KJ, Moeini M, Russell DM. Electromyographical Assessments of Recommended Neck and Trunk Positions for Dental Hygienists. Journal of Dental Hygiene: JDH, 2021; 95(5): 6-13.

- Möller A, Spangenberg J. Stress and coping amongst South African dentists in private practice. The Journal of the Dental Association of South Africa, 1996; 51(6): 347-357.

- El Elagra M, Rayyan M, Bin Razin K, Alanazi A, Aldossary M, Alqahtani A, et al. Self-reported stress among senior dental students during complete denture procedures. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 2022; 11(11): 6726. https://doi.org/10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1761_21

- Silverstein ST, Kritz-Silverstein D. A longitudinal study of stress in first-year dental students. Journal of Dental Education, 2010; 74(8): 836-848.

- Sfeatcu R, Balgiu B, Parlatescu I. New psychometric evidences on the Dental Environment Stress questionnaire among Romanian students. Journal of Education and Health Promotion, 2021; 10(1): 296. https://doi.org/10.4103/jehp.jehp_4_21

- Ahola K, Hakanen J. Job strain, burnout, and depressive symptoms: A prospective study among dentists. Journal of Affective Disorders, 2007; 104(1): 103-110.

- Basudan S, Binanzan N, Alhassan A. Depression, anxiety and stress in dental students. International Journal of Medical Education, 2017; 8: 179-186. Doi: 10.5116/ijme.5910.b961

- Wicke FS, Ernst M, Otten D, Werner A, Dreier M, Brähler E, et al. The association of depression and all-cause mortality: Explanatory factors and the influence of gender. Journal of Affective Disorders, 2022; 303: 315–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.02.034

- Goldman LS, Nielsen NH, Champion HC. Awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 1999; 14(9): 569-580.

- Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Hahn SR, Morganstein D. Cost of lost productive work time among US workers with depression. Journal of the American Medical Association, 2003; 289(23): 3135-3144.

- Petersen MR, Burnett CA. The suicide mortality of working physicians and dentists. Occupational Medicine, 2008; 58(1): 25-29.

- Newbury-Birch D, Lowry R, Kamali F. The changing patterns of drinking, illicit drug use, stress, anxiety and depression in dental students in a UK dental school: A longitudinal study. British Dental Journal, 2002; 192(11): 646-649.

- Costa Jr PT, McCrae RR. Four ways five factors are basic. Personality and Individual Differences, 1992; 13(6): 653-665.

- Goldberg LR. The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist, 1993; 48(1): 26.

- Aeon B, Faber A, Panaccio A. Does time management work? A meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 2021; 16(1): e0245066. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245066

- Wilmot MP, Ones DS. A century of research on conscientiousness at work. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 2019; 116(46): 23004-23010.

- Flett GL, Hewitt P. When does conscientiousness become perfectionism? Current Psychiatry, 2007; 6(7): 49.

- Friedman H. Neuroticism and health as individuals age. Personality Disorders, 2019; 10(1): 25-32. Doi: 10.1037/per0000274

- Watson D, Clark LA, Harkness AR. Structures of personality and their relevance to psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 1994; 103(1): 18.

- Bolger N, Zuckerman A. A framework for studying personality in the stress process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1995; 69(5): 890.

- McCrae RR, Costa PT. Personality in Adulthood: A Five-Factor Theory Perspective. New York , Guilford Press, 2003.

- Grant S, Langan-Fox J. Personality and the occupational stressor-strain relationship: The role of the Big Five. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 2007; 12(1): 20.

- Tyssen R, Dolatowski FC, Røvik JO, Thorkildsen RF, Ekeberg Ø, Vaglum P. 2007.

- Vollrath M, Torgersen S. Personality types and coping. Personality and Individual Differences, 2000; 29(2): 367-378.

- Bokhari A, Banta JE, Ghamsary M, Marmolejo anta JM, Martin LR. Stress and Depression among Dental Students at Loma Linda University: A Descriptive Study. International Journal of Medical Science and Dental Research, 2003; 6(5): 69-77. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.8387598

- Westerman GH, Grandy TG, Ocanto RA, Erskine CG. Perceived sources of stress in the dental school environment. J Dent Educ, 1993; 57(3): 225-231.

- Eaton WW, Smith C, Ybarra M, Muntaner C, Tien A. Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale: review and revision (CESD and CESD-R). American Psychological Association, 2004; 3(3): 363-377.

- Goldberg LR. The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment, 1992; 4: 26-42.

- Raynor DA, Levine H. Associations between the five-factor model of personality and health behaviors among college students. Journal of American College Health, 2009; 58(1): 73-82.

- Hakulinen C, Elovainio M, Pulkki-Raback L, Virtanen M, Kivimaki M, Jokela M. Personality and depressive symptoms: Individual participant meta-analysis of 10 cohort studies. Depression and Anxiety, 2015; 32: 461-470.

- McCrae RR, John OP. An introduction to the fivefactor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 1992; 60(2): 175-215.

- Personality traits and types predict medical school stress: A six-year longitudinal and nationwide study. Medical Education, 41(8): 781-787.