Alveolar Hemorrhage Complicating Thrombolysis with Tenecteplase for SCA ST+: A Rare Complication in One Case with a Review of the Literature

Marouane Bouazaze*, Asmaa Bouamoud, Zaineb Bourouhou, Jamila Zarzur and Mohamed Cherti

Department of Medicine, Mohamed V of Rabat, Morocco

Received Date: 09/10/2023; Published Date: 14/03/2024

*Corresponding author: Bouazaze Marouane, Department of Medicine, Mohamed V of Rabat, Morocco

Summary

Alveolar Hemorrhage (AH) is a heterogeneous clinical syndrome with a high mortality rate, characterized by significant bleeding into the alveolar spaces. HA secondary to systemic thrombolysis therapy in acute myocardial infarction is an uncommon but life-threatening complication and can lead to acute respiratory failure. This entity is rarely reported in the literature. We report a case of acute HA after intravenous thrombolysis with Tenecteplase for acute myocardial infarction, and discuss risk factors as well as clinical and radiological evidence supporting the diagnosis. We also review the few previously published case reports in this context, and compare our results with those reported in the literature.

Introduction

Alveolar Hemorrhage (AH) is a rare disease, characterized by the presence of blood at the level of the pulmonary acinus, related to a lesion of the alveolar-capillary barrier (excluding flooding of bronchial origin), more rarely of the pre-capillary arteriole and the post-capillary venule [1].

It is a therapeutic emergency because it can quickly lead to acute asphyxiating respiratory failure with death [2].

The current classifications of H A are based on the determination of the origin of HA according to whether or not it is the result of treatment with corticosteroids or immunosuppressants, thus distinguishing between:

◦ HA of certain immune origin,

◦ HA of non-immune origin,

◦ HA with no apparent cause (idiopathic HA).

Immune HAn on are H A of cardiovascular origin, H A related to haemostasis disorders, H A of medicinal and toxic origin, H A by negative pressure oedema, HA of septic origin, Tumor H A, etc. [1].

Somenon-immune H A may be linked to autoimmune mechanisms, such as drug-induced HA [1].

The most commonly incriminated drugs are amiodarone, D-penicillamine (trolovol®), anticoagulants, antiaggregants and fibrinolytics. Inhalation of certain toxins such as cocaine can also lead to the occurrence of HIA. Silicones used for aesthetic purposes may be accompanied in some cases by intraalveolar haemorrhage [1,2].

Pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage is an extremely rare and life-threatening complication of intravenous thrombolytic therapy. So far, only a few cases have been reported in the literature [3].

We report here a case of acute alveolar hemorrhage complicating thrombolytic treatment in myocardial infarction.

Through our case, we address the risk factors, clinical and radiographic findings that suggest and support the diagnosis, as well as the management issues related to this unusual and life-threatening situation.

Clinical Case

This is a 70-year-old patient with FDRCVx: type 2 diabetes of recent discovery, without any particular ATCD. Admitted to an inferobasal STEMI array, he was immediately given a loading dose of aspirin and Clopidogrel, and then had successful thrombolysis with tenecteplase. 24 hours later, he developed hemoptoid sputum. On physical examination, it was apyretic, hemodynamically stable with BP: 140/75 mmhg, HR: 75 BPM, eupneic with RF: 18 cpm, Sp02: 98% in ambient air.

Pulmonary auscultation revealed crackling rattles limited to the pulmonary bases more pronounced on the right, with no signs of heart failure.

Chest X-ray has objectified bilateral alveolar infiltrates. At the same time, the laboratory work-up showed a decrease in HB levels from 16.6 g/dl to 15 g/dl, with normal platelet and white blood cell counts.

Faced with this context of haemoptoid sputum with a drop in HB levels, bilateral alveolar infiltrates on chest x-ray, the most likely diagnosis was that of alveolar hemorrhage.

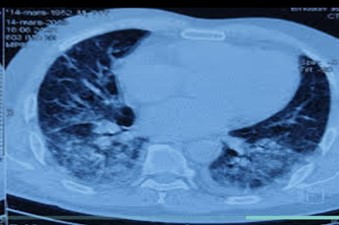

Chest CT showed foci of alveolar condensation strongly suggestive of alveolar hemorrhage (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Chest CT scan showing foci of alveolar condensation strongly suggestive of alveolar hemorrhage.

We decided to stop the anticoagulation and maintain the double antiplatelet aggregation.

Transthoracic echocardiography revealed akinesia of the middle and basal segments of the inferior and lateral walls with normal filling pressures.

The patient presented with sustained VT that was well tolerated hemodynamically prompting coronary angiography which revealed a subocclusive lesion of proximal Cx with TMI III flow, successfully treated with active stent placement.

Faced with the persistence of the VT, the patient received a CEE (200 D) 2 H after the performance of the ATL with return to sinus rhythm.

The evolution was marked by the onset of dyspnea with a polypnea at 30 cpm and a desaturation at 85 in ambient air, with the presence of bilateral crackling rails reaching mid-field, echocardiographic control showed high filling pressures without added kinetic disorders. The patient was injected on furosemide. A follow-up CT scan was performed showing a stationary aspect of the alveolar hemorrhage.

Two days later, the patient presented with greenish sputum with an increase in the biological markers of inflammation, prompting the introduction of a double antibiotic therapy based on amoxicillin and ciprofloxacin. 48 hours later, the patient worsened his respiratory distress with a desaturation to 70 in the ambient air and appearance of signs of struggle, the chest x-ray showed a worsening of the lesions with bilateral opacities reaching to the summits. The patient was transferred to the intensive care unit and intubated on the basis of respiratory criteria.

The aftermath was marked by the onset of severe ARDS with the death of the patient.

Discussion

The available literature does not cover the exact incidence of this complication, but rather consists of a few case reports [3].

Chang YC et al [4] retrospectively reviewed 2,634 patients with acute STEMI who received thrombolytic therapy and reported that hemoptysis occurred in 11 patients (0.4%).

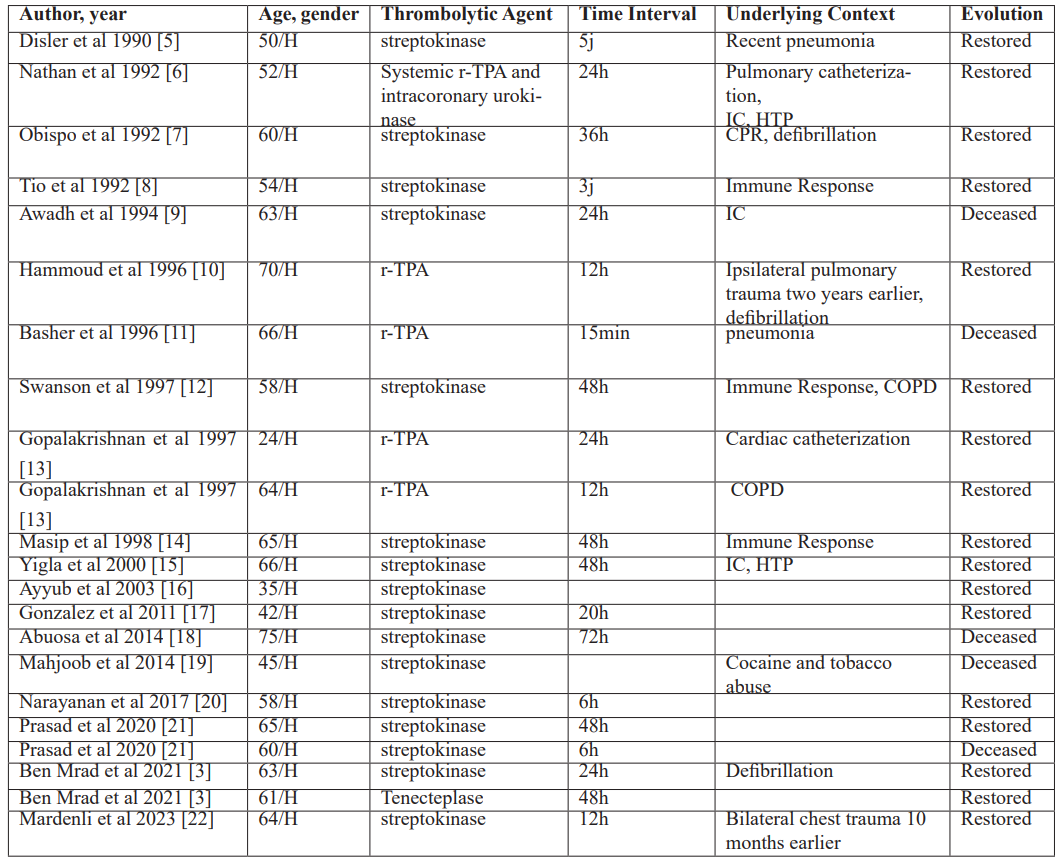

Table 1: Described cases of alveolar haemorrhage after thrombolytic therapy for myocardial infarction.

Four fibrinolytic agents were used in these cases: streptokinase, urokinase and actilyse (Alteplase-rtPA), tenecteplase ®. Most of these patients received streptokinase,

Tothe best of our knowledge, only one case associated with Tenecteplase (Metalysis) has been previously reported in the literature [3].

Through the analysis of these cases, we find that HA usually occurs from a few hours to 5 days after thrombolysis.[ [3]

The literature review identified 23 cases [3,22]. Surprisingly, all 23 patients (including ours) were male, ranging in age from 24 to 75 years, making male a predisposing factor [3]. Streptokinase was the thrombolytic agent in 16 of 23 patients (69.5%) [3,21]. Streptokinase immune reactions that range from simple allergy to anaphylactic shock may be a contributing factor. It has been suggested that immune-mediated capillaritis maybe a possible etiology of HA following streptokinase administration [3,21,23]

The pathogenesis of HA attributable to thrombolytic therapy remains uncertain and may be explained by pre-existing fibrinolytic states, the presence of parenchymal abnormalities, or an immune response to streptokinase causing pulmonary capillaritis as proposed [20].

It was mentioned that some potential cofactors may predispose to this complication, such as underlying lung diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, anterior emphysema), recent pneumonia, cardiac catheterization, arrhythmias requiring defibrillation shock or cardiopulmonary resuscitation, heart failure, and substance abuse such as cocaine and tobacco [24]. Green et al [25] described that some patients with alveolar hemorrhage had capillaritis, suggesting an immune reaction since streptokinase is associated with a wide range of allergic reactions, such as anaphylaxis, bronchospasm, and type III immune reactions. Tio et al [8] described the discovery of antibodies to streptokinase in HA patients treated with thrombolytics, which would support this theory. However, in some cases, no predisposing factors have been identified.

For our patient, pneumonia and defibrillation after thrombolytic administration could be the cause of the worsening HA.

Typically, the diagnosis of HA is evoked in the clinical triad of haemoptysis, anemia and radiological pulmonary infiltrates, with a variable mode of onset (insidious to abrupt). Hemoptysis is rarely abundant due to its distal nature. It may be associated with coughing or chest pain. Frequent anaemia, possibly of rapid onset with a sudden loss of 10 to 20 g/L, given thealveolar surface during active H A [1].

Chest X-rays may be normal (about 5%). Anemia may also be missing [1]. It varies depending on when it is done in relation to the beginning of the bleeding, and its intensity. In the initial phase, bilateral micronodular images are observed, which will often converge and give predominantly perihilar and peribasal alveolar opacities, sparing the apexes and costophrenic angles [21]. These opacities over time will give way to interstitial opacities (indicating the resorption of the hemorrhagic alveolitis in the interstitium) in principle transient (10 days to 2 weeks) [1].

Chest computed tomography (CT) scans are of little interest in the acute phase and can only be considered in stable patients. It may show areas of bilateral alveolar condensation and/or frosted glass, diffuse, sometimes associated with cross-linking giving a crazy paving appearance [1].

Diagnostic confirmation is based on bronchial endoscopy and AML, the appearance of which varies according to the length of the intraalveolar hemorrhage. A lung biopsy is not necessary [1].

When the diagnosis is suggested, bronchial endoscopy with Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) is the gold standard to confirm the diagnosis. However, this is usually not possible. In cases of post-thrombolysis H A reported in the literature, these examinations have not been performed [3].

The prognosis can sometimes be life-threatening. In some all-cause H series, between 20 and 70% of patients are ventilated and 50 to 90% are on dialysis. Mortality ranges from 20% to 100% with early mortality (first 15 days) attributable to HA of about 10% [1].

To identify patients at risk of hospital death, the following parameters are available in the first 24 hours: resuscitation severity scores (IGS II, APACHE II), an LDH level greater than twice normal, the presence of shock or severe kidney damage [1].

Regarding the cases of post-thrombolysis H A described in the literature, the clinical course was good in about 80% of cases with complete recovery within one to two weeks. The prognosis depends on the extent of the myocardial infarction, the volume of the hemorrhage and the degree of cardiorespiratory involvement.

Prior to our publication, only 23 cases were reported in theliterature with five deaths; therefore, the mortality rate was 21%[3].

Symptomatic treatment of acute respiratory failure has no specificity. If mechanical ventilation becomes necessary, it should limit barotrauma. The volume of blood glucose levels should be assessed regularly, as any overload is deleterious, especially in the case of associated renal failure. Any abnormality in haemostasis can aggravate the disease: non-essential antiaggregation or anticoagulant treatments should be discontinued.

In severe cases, some people use desmopressin or corticosteroid therapy, the effectiveness of which is controversial [1].

Antifibrinolytic agents, such as tranexamic acid, were used in one case.

Conclusion

Alveolar hemorrhage is an unusual complication of thrombolytic treatment of myocardial infarction, reported especially with streptokinase. The diagnosis of alveolar haemorrhage is based on a set of arguments, as the signs are not specific and can delay the diagnosis. Diagnosis should be considered in patients with respiratory distress associated with haemoptysis, acute anaemia, and pulmonary infiltrates after thrombolysis. Early diagnosis and therapeutic management are essential to prevent acute respiratory failure and death. Risk factors and a probable etiology of this complication should be investigated.

References

- Parrot A, Fartoukh M, Cadranel J, Intraalveolar hemorrhage. Journal of Respiratory Diseases, 2015; 32(4): pp. 394-412.

- Parrot A, et al. Intraalveolar hemorrhages. Diagnosis and treatment. Resuscitation, 2005; 14(7): pp. 614-620.

- Mrad I, et al. Alveolar Hemorrhage Following Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction: Two Case Reports and Literature Review. Open Access Emergency Medicine, 2021; 13: p. 399-405.

- Chang Y-C, et al. Significance of hemoptysis following thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Chest, 1996; 109(3): p. 727-729.

- Disler L, Rosendorff A. Pulmonary hemorrhage following intravenous streptokinase for acute myocardial infarction. International journal of cardiology, 1990; 29(3): p. 387-390.

- Nathan PE, et al. Spontaneous Pulmonary Hemorrhage Following Coronary Thrombolysis. Chest, 1992; 101(4): p. 1150-1152.

- Cuéllar Obispo E, et al. A diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage following thrombolytic therapy in an acute myocardial infarct]. Spanish Journal of Cardiology, 1992; 45(6): p. 421-424.

- Tio R, Voorbij RHAM, Enthoven R. Adult respiratory distress syndrome after streptokinase. The American Journal of Cardiology, 1992; 70(20): p. 1632-1633.

- Awadh N, et al. Spontaneous Pulmonary Hemorrhage After Thrombolytic Therapy for Acute Myocardial Infarction. Chest, 1994; 106(5): p. 1622-1624.

- Hammoudeh AJ, Haft JI, Eichman GT. Hemoptysis and unilateral intra‐alveolar hemorrhage complicating intravenous thrombolysis for myocardial infarction. Clinical cardiology, 1996; 19(7): p. 595-596.

- Basher AW, et al. Fatal hemoptysis during coronary thrombolysis. Journal of Thrombosis and Thrombolysis, 1996; 3: p. 87-89.

- Swanson GA, Kaeley G, Geraci SA. Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage after streptokinase administration for acute myocardial infarction. Pharmacotherapy: The Journal of Human Pharmacology and Drug Therapy, 1997; 17(2): p. 390-394.

- Gopalakrishnan D, et al. Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage complicating thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Clinical cardiology, 1997; 20(3): p. 298-300.

- Masip J, Vecilla F, Paez J. Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage after fibrinolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. International journal of cardiology, 1998; 63(1): p. 95-97.

- Yigla M, et al. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhage following thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. Respiration, 2000; 67(4): p. 445-448.

- Ayyub M, et al. Diffuse alveolar hemorrhages and hemorrhagic pleural effusion after thrombolytic therapy with streptokinase for acute myocardial infarction. Saudi medical journal, 2003; 24(2): p. 217-220.

- Gonzalez A, et al. Alveolar hemorrhage as a complication of thrombolytic use. MEDICINA (Buenos Aires), 2011; 71(6): p. 547-549.

- Abuosa AM, El-Sheikh AH, Kinsara AJ. Abnormal Chest X-ray Postmyocardial Infarction. Heart Views, 2014; 15(4).

- Mahjoob MP, Khaheshi I, Paydary K. Diffuse pulmonary hemorrhage after fibrinolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction in a cocaine abuser patient. Heart Views: The Official Journal of the Gulf Heart Association, 2014; 15(3): p. 83.

- Narayanan S, et al. Pulmonary alveolar hemorrhage following thrombolytic therapy. Int Med Case Rep J, 2017; 4(10): p. 123-125.

- Prasad K, et al. Pulmonary haemorrhage following thrombolysis with streptokinase in myocardial infarction. BMJ Case Reports CP, 2020; 13(1): p. e232308.

- Mardenli M, et al. Post thrombolytic alveolar hemorrhage: a case report. Oxford Medical Case Reports, 2023; 2023.

- Green RJ, et al. Pulmonary capillaritis and alveolar hemorrhage: update on diagnosis and management. Chest, 1996; 110(5): p. 1305-1316.

- Prasad K S P, Kanabar K, Vijayvergiya R. Pulmonary haemorrhage following thrombolysis with streptokinase in myocardial infarction. BMJ Case Rep, 2020; 13(1): e232308. doi:10.1136/bcr-2019-232308,

- Green RJ, et al. Pulmonary capillaritis and alveolar hemorrhage. Update on diagnosis and management. Chest Jul, 1997; 110: p. 1305-1316.