Hepatic Hematoma After Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography in a Patient with Mirizzi Syndrome: Case Report and Summary of Literature

Ana Victoria Espinosa De Los Monteros-Gonzalez*

General Surgery Department. Mexican Institute of Social Security, National Medical Center of the West “Lic. Ignacio García Téllez”, Mexico

Received Date: 28/09/2023; Published Date: 01/03/2024

*Corresponding author: Dr. Ana Victoria Espinosa de los Monteros González. M.D., General Surgery Department. Mexican Institute of Social Security. National Medical Center of the West “Lic. Ignacio García Téllez”, Mexico

Abstract

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is currently the most widely used minimally invasive technique for the diagnosis and treatment of biliary and pancreatic diseases. Although uncommon, subcapsular hematoma is a known cause of morbidity. We present the case of a 43-year-old Mexican woman who presented with pain and anemia immediatley after undergoing ERCP for obstructive jaundice with suspicion of Mirizzi syndrome. She was hemodynamically stable, and the computed tomography (CT) showed a 205 x 148 x 77 cm subcapsular hematoma managed conservatively with crystalloid fluids, blood products, antibiotics and oral proteolytic agent. At the two-month follow up, the hematoma remained stable, and there were no signs of liver failure or compressive symptoms. Treatment selection should be based on an individual basis, adopting an approach similar to that of hepatic trauma.

Keywords: Endoscopic retrograde; Cholangiopancreatography; Hepatic subcapsular hematoma; Mirrizzi syndrome; Trypsin

Introduction

ERCP was developed in 1968 and is currently the most commonly performed minimally invasive technique for the diagnosis and treatment of biliary and pancreatic diseases. However, it has been associated with the highest incidence of complications among all endoscopic procedures of the upper gastrointestinal tract [1]. Even in experienced centers, the rate of certain complications like pancreatitis can be as high as 10%, while for others likeduodenal perforation it can be as low as 0.08%. The incidence of mortality incidence ranges from 0.3% to 1%, especially when therapeutic procedures are involved [2,3].

Subcapsular hematoma is a rare cause of morbidity, with only 63 cases reported in the literature since its first publication in 2000. Four of these resulted in a fatal outcome [1]. Diagnostic and management criteria have not been established. As a result, maintaining a high index of suspicion and providing prompt, individualized treatment is crucial in preventing mortality. In the following section, we present a case of this uncommon condition presented to our hospital unit.

Clinical Case

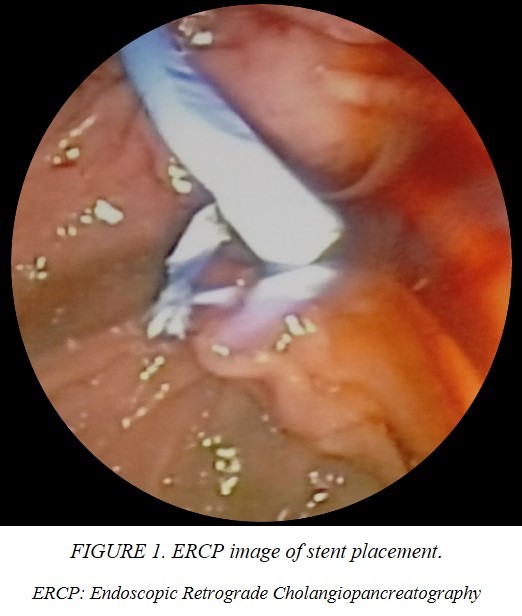

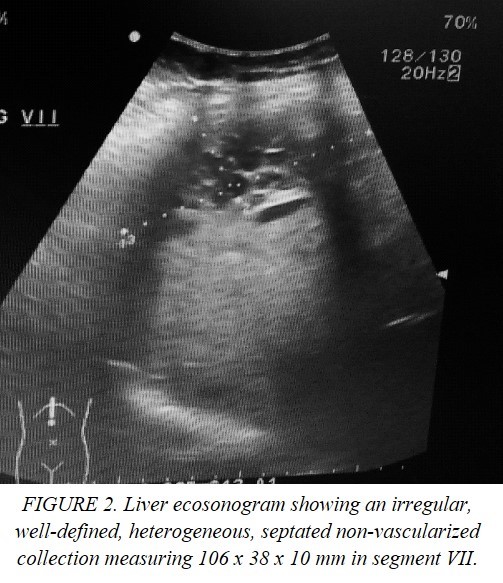

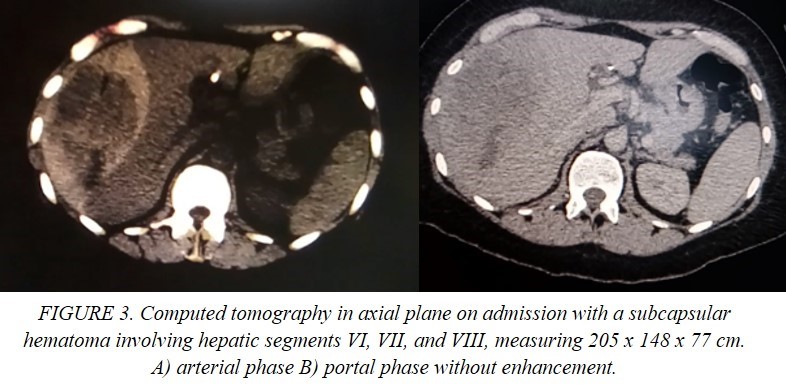

This is the case of a single 43-year-old Mexican woman who presented with icterus, asthenia, acholia, choluria and pruritus, accompanied by stabbing pain in the right hypochondrium two weeks after an acute episode of optic neuritis managed with systemic steroid boluses and use of cannabidiol for three days on her own decision. She had a family history of pancreatic cancer, cholelithiasis and unspecified hepatic tumors. She recently underwent a ketogenic dietary and lost 14 kg in 4 months. Her blood chemistry revealed elevated levels of transaminases, alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin (2.6 mg/dl) with predominance of direct fraction (2.3 mg/dl). Coagulation tests and blood cell count (hemoglobin 14 g/dl) were normal. The echosonogram reported alithiasic cholecystitis, intrahepatic bile duct dilatation, and hepatomegaly. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with drug-induced hepatitis, and jaundice resolved spontaneously. Nevertheless, the patient continued to experience symptoms and one month after the initial evaluation, jaundice, recurred. A simple CT scan was performed, which showed dilatation of the intrahepatic bile duct and common hepatic duct. The gallbladder was observed to have liquid content and material of varying densities that may be indicative of non-calcified calculi or biliary sludge. Additionally, the gallbladder was protruding towards the common hepatic duct, suggestive of Mirizzi syndrome and choledocholithiasis. ERCP was indicated finding a non-mobile eccentric stenosis of the common bile duct at its junction with the common hepatic duct with suprastenotic dilatation of 12 mm and hemobilia on manipulation, consistent with a diagnosis of Mirizzi syndrome. A 10 Fr stent was implanted (Figure 1), and a brush biopsy was performed, ruling out gallbladder carcinoma. Almost immediately after the procedure the patient experienced severe pain in the right subcostal region radiating to the ipsilateral shoulder, nausea, vomiting and mucotegumentary pallor. She was then referred to the emergency department of a specialized center. On admission, she was hemodynamically stable, but had moderate anemia, elevated transaminases and alkaline phosphatase. Autoimmune and viral etiologies were excluded. The echosonogram demonstrated a well-defined, irregularly shaped collection without blood-flow in the hepatic segment VII with a volume of approximately 216 cc (Figure 2). In addition, the CT scan showed pneumobilia, perihepatic fat striation, and delimitated the collection without contrast enhacement, with hematoma-like density involving segments VI, VII, and VIII, with dimensions of 205 x 148 x 77 cm, and a volume of approximately 1214 cc (Figure 3).

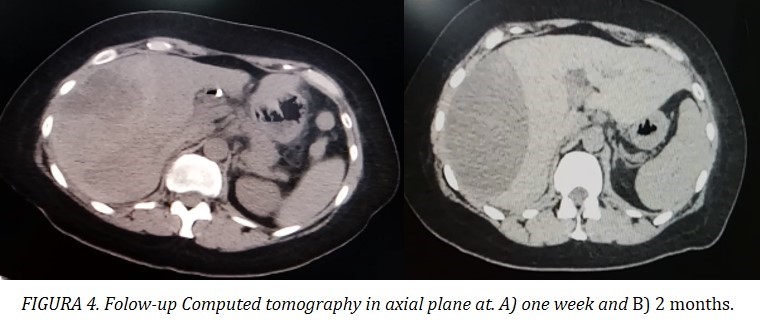

Consequently, she was admitted to the general surgery department for close monitoring and complementary diagnostic tests. Due to a 1 mg/dl drop in hemoglobin, two units of concentrated red blood cells were transfused. The patient remained normotensive and showed no signs or laboratory findings of sepsis. Antibiotic prophylaxis with meropenem was administered. The patient’s bilirubin levels normalized. Control ultrasounds and CT scans showed no increase in hematoma volume (Figure 4). Angiotomography excluded active bleeding. After evaluation by an intervetional radiology, she was determined not to be a candidate for percutaneous drainage. She was prescribed oral trypsin/chemotrypsin and discharged after 2 week, pending MRI results for assessment of biliary tract morphology.

Discussion

The use of endoscopic techniques is advised, with the potential risks carefully weighed against its benefits. The incidence of complications ranges from 2.5% to 8%, of which 1.67% are severe [3,4]. Mortality is higher in therapeutic ERCP at 0.4-0.5% compared to 0.2% in diagnostic ERCP [5].

Clinically evident bleeding occurs in 0.1% to 2% of cases, typically at the site of sphincterotomy [6]. Subcapsular hematoma is another infrequent hemorrhagic complication, first reported in 2000 by Ortega et al [7]. The exact incidence is difficult to determine because many patients may course asymptomatically, and post ERCP follow-up imaging studies are not routinely, unless indicated for other reasons [8].

The pathophysiology of this condition is not fully understood, but two potential mechanisms have been proposed. The first involves direct injury to small intraparenchymal vessels caused by the guidewire. The second suggests a lesion of the Glissonian pedicle caused by traction of the ballon during stone extraction [2]. The use of a guidewire was mentioned in 80.3% of the reviewed publications. Nonetheless, in the remaining 19.7%, no statement was made in this regard, as in this case, being unable to ascertain the device responsible for the lesion.

García et al. reported a mean age of presentation of 59 years, with a gender distribution of 58% women and 35% men. Choledocholithiasis was the most common indication for ERCP (72.7%), followed by stent replacement (6%) and ampullary tumors (6%), which coincides with characteristics of or case. Only 6.4% of the reports confirmed the use of anticoagulant therapy [9].

The latest comprehensive review reveals that the most common symptoms of presentation are abdominal pain (83%), anemia (56.7%), hypotension (28.7%), fever (18.3%) and omalgia (13.3%). The majority of cases are diagnosed within the first 48 h post-procedure (77.8%), with almost half of them (40.7%) presenting immediately (within the first 12 h) [1] as seen in the patient described. However, Roldan et al referred a case identified 15 days after the endoscopic intervention [10].

Cases mentioning a decrease in hemoglobin have exhibited a higher frequency of surgical or percutaneous intervention (63%) [9], but other laboratory tests are unspecific. The percentage of hematoma rupture is 23.7%, resulting in a mortality rate of 21.4% [1]. This underscores the importance of early recognition and continuous monitoring of indicators of hypovolemia and peritoneal irritation.

The most utilized diagnostic method is CT scan (91.4%), with concurrent application of ultrasound at 22.4%. This can be attributed to the necessity for thorough characterization before making therapeutic decisions, although hemodynamic instability may preclude its use. The predominant location is the right lobe (87.3%), as in the case discussed, with no correlation to mortality [1].

Conservative approach is successful in only 39.3% of patients. The use of proteolytic enzymes has not been previously mentioned, and it did not affect hematoma size at two months, probably due to initial size (greater than 1000 cc). When evacuation is required surgery is performed in 27.9% of patients, while percutaneous drainage is implemented in 22.95% of subjects. Embolization is the least frequent option, indicated in only 8.2% of patients. Either large hematomas may be candidates for non-operative management [8,11] or small sizes lesions may necessitate exploratory laparotomy [12]. Therefore, we propose extrapolating liver trauma classification and treat accordingly based on extension/depth, hemodynamic status, and angiothomography result to discard positive blush [13], as well as signs of liver failure or compression symptoms. Currently, there are insufficient data to determine the safety of conservative management in the setting of an additional indication for surgery or the appropriate time for cholecystectomy. Mirizzi syndrome has not been reported in previous cases, and the presence of a hematoma may difficult cholecystectomy.

In addition to the risk of rupture, sepsis is also a concern. Antibiotics are used and recommended by most authors (70.9%)[1,14], with Pivetta et al being the only to specify the agents used (ciprofloxacin and metronidazole) [1]. The isolated microorganisms in the reports that mentioned cultures were Citrobacter freundii and Escherichia coli, which is consistent with the microbiology of biliary tract infections described in the 2018 Tokyo guidelines [15]. As a result, antimicrobial agents should be selected based on these recommendations.

Conclusion

In conclusion, subcapsular hematoma is a rare event following ERCP, typically presenting within 48 hours after the procedure. Early diagnosis and treatment require high index of suspicion and treatment should be analogous to the liver trauma grade of the lesion and hemodynamics along with administration of adequate antibiotic prophylaxis to avoid hepatic abscess and cholangitis. The addition of proteolytic enzymes as adjuvant therapy may constitute an area for further study to determine the effect on reducing the frequency of surgical intervention in lesions of similar or smaller volume.

Acknowledgements: None

Conflict of interest: The author declares to have no conflicts of interest.

Funding: The author received no funding for this work

Ethical approval: Written informed consent was obtained from the patient available for review on request by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

- Pivetta LGA, da Costa Ferreira CP, de Carvalho JPV, Konichi RYL, Kawamoto VKF, Assef JC, et al. Hepatic subcapsular hematoma post-ERCP: Case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep, 2020; 72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijscr.2020.05.074.

- Sommariva C, Lauro A, Pagano N, Vaccari S, D’Andrea V, Marino IR, et al. Subcapsular Hepatic Hematoma Post-ERCP: Case Report and Review of the Literature. Dig Dis Sci, 2019; 64. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10620-019-05679-3.

- Manoharan D, Srivastava DN, Gupta AK, Madhusudhan KS. Complications of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: an imaging review. Abdominal Radiology, 2019; 44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00261-019-01953-0.

- Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Napolitano G, Niro G, Valvano MR, Spirito F, et al. Incidence rates of post-ERCP complications: A systematic survey of prospective studies. American Journal of Gastroenterology, 2007; 102. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01279.x.

- Freeman ML, Nelson DB, Sherman S, Haber GB, Herman ME, Dorsher PJ, et al. Complications of Endoscopic Biliary Sphincterotomy. New England Journal of Medicine, 1996; 335. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm199609263351301.

- Rustagi T, Jamidar PA. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography-related adverse events. General overview. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am, 2015; 25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.giec.2014.09.005.

- Ortega Deballon P, Fernández Lobato R, García Septiem J, Nieves Vázquez MA, Martínez Santos C, Moreno Azcoita M. Liver hematoma following endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Surg Endosc, 2000; 14.

- Gárate FO, Irarrazaval J, Galindo J, Balbontin P, Manrquez L, Plass R, et al. Subcapsular hepatic hematoma post ERCP: A rare or an underdiagnosed complication? Endoscopy, 2012; 44. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0031-1291493.

- García Tamez A, López Cossio JA, Hernández Hernández G, González Huezo MS, Rosales Solís AA, Corona Esquivel E. Subcapsular hepatic hematoma: An unusual, but potentially life-threating post-ERCP complication. Case report and literature review. Endoscopia, 2016; 28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.endomx.2016.04.001.

- Roldán Villavicencio JI, Calvo MP, Mateo MG. Post-ERCP hepatic subcapsular hematoma, from conservative therapy to emergency surgery: An unusual though extremely serious complication. Revista Espanola de Enfermedades Digestivas, 2019; 111. https://doi.org/10.17235/REED.2019.5787/2018.

- Pozo Prieto D, Moral I, Poves E, Sanz C, Martín M. Subcapsular hepatic hematoma following ERCP: Case report and review. Endoscopy, 2011; 43. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0030-1256267.

- Kilic A, Acar A, Canbak T, Basak F, Kulali F, Ozdil K, et al. Subcapsular liver hematoma due to endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography: case report. Medicine Science | International Medical Journal, 2016; 5. https://doi.org/10.5455/medscience.2016.05.8492.

- Coccolini F, Coimbra R, Ordonez C, Kluger Y, Vega F, Moore EE, et al. Liver trauma: WSES 2020 guidelines. World Journal of Emergency Surgery, 2020; 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13017-020-00302-7.

- de la Maza Ortiz J, García Mulas S, Ávila Alegría JC, García Lledó J, Pérez Carazo L, Merino Rodríguez B, et al. Hematoma subcapsular hepático tras colangiopancreatografía retrógrada endoscópica. Una complicación rara y con elevada morbimortalidad. Gastroenterol Hepatol, 2019; 42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gastrohep.2018.01.003.

- Gomi H, Solomkin JS, Schlossberg D, Okamoto K, Takada T, Strasberg SM, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: antimicrobial therapy for acute cholangitis and cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci, 2018; 25. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhbp.518.