Approach in shock in pediatrics … when minutes matter...!

Said Eldeib1,*, Jayaraj Damodaran1, Ali Wahba2, Ayman Khayal3, Mohamed Atif Attia3, Ahmed Elbarmeshty4, Abedallattif khalloof5 and Hany Mousa5

1Department of pediatrics, ADSCC/Yas clinic Hospital, UAE

2Department of pediatrics, SSMC hospital, AD, UAE

3Department of pediatrics, SKMC hospital, AD, UAE

4Department of pediatrics, Munich medical &rehabilitation center, Al Ain UAE

5Department of pediatrics, Mediclinc Al Jawhraa Hospital Al Ain, UAE

Received Date: 14/03/2023; Published Date: 31/05/2023

*Corresponding author: Dr. Said Eldeib, Department of pediatrics ADSCC/ Yas clinic Hospital, Abu Dhabi, UAE

Abstract

Early recognition of shock in children is crucial for optimal outcome but is not always obvious. Clinical experience, gut feeling, and careful and repeated interpretation of the vital parameters are essential to recognize and effectively treat the various forms of shock.

The clinical signs and symptoms of shock in newborns and children are often more subtle compared to adults. Recurring, avoidable factors for optimal outcome include failure of health care workers to recognize shock at the time of presentation. Children are able to compensate a shock state for longer periods than adults resulting in a sudden, sometimes irreversible, cardiopulmonary collapse. Different forms of shock, their therapy, and frequent errors are depicted and illustrated with practical examples.

Inappropriate volume for fluid resuscitation (usually too little for children with sepsis or hypovolemic shock, but possibly too much for those with cardiogenic shock also Failure to reconsider possible causes of shock for children who are getting worse or not improving, Failure to recognize and treat obstructive shock.

The management of children with shock is challenging. Some pitfalls include, Failure to recognize nonspecific signs of compensated shock (ie, unexplained tachycardia, abnormal mental status, or poor skin perfusion) could be due to Inadequate monitoring of response to treatment

Keywords: Shock in children; Cardiac failure; Volume expanders; Anaphylaxis; Arrythmia

Introduction

Shock: is a condition characterized by a significant reduction in tissue perfusion, resulting in decreased tissue oxygen delivery [1].

- Compensated shock: The body compensate for diminished perfusion and SBP is maintained within the normal range by tachycardia and peripheral vasoconstriction (cool skin and decreased peripheral pulses) [2].

- Hypotensive shock: Compensatory mechanisms are overwhelmed. Heart rate is markedly elevated, and hypotension develops.

- Irreversible shock: Bradycardia and blood pressure becomes very low, irreversible organ damage and death [2].

Classification of shock

- Hypovolemic shock

- Distributive shock

- Septic shock

- Anaphylaxis

- Neurogenic shock

- Cardiogenic shock

- Obstructive shock [3]

The Pathophysiology of Shock

Shock is characterized by a relative imbalance between the delivery of oxygen and metabolic substrates and the metabolic demands of the cells and tissues of the body. While the shock state most commonly occurs in the setting of decreased oxygen delivery, it is certainly feasible that excessive metabolic demands could produce a similar pathologic state. However, the body’s compensatory mechanisms are able to adjust to meet even incredibly high metabolic demand, so that a state of shock will usually only occur in the setting of decreased oxygen and substrate delivery [4].

Under resting conditions, with normal distribution of cardiac output, oxygen delivery (DO2) is more than adequate to meet the total oxygen requirements of the tissues needed to maintain aerobic metabolism, referred to as oxygen and VO2 result in a mathematical coupling of measurement errors in the shared variables resulting in false correlation between oxygen delivery and consumption. In order to avoid potential mathematical coupling, oxygen consumption and delivery should be determined independent of each other.

Studies in which VO2 was directly measured (rather than calculated) have largely disproved this pathologic supply dependency hypothesis. Regardless, during the shock state, the body’s compensatory mechanisms, as well as our therapeutic efforts, are largely directed at optimizing the balance between oxygen delivery and consumption [5].

Common Features:

Early

- Tachycardia

- Compromised organ perfusion

- Skin: cool, clammy, pale, or mottled

- Brain: drowsy, lethargy.

- Kidneys: Oliguria.

- Lactic acidosis

Late: hypotension [6]

Rapid Assessment:

Pediatric Assessment Triangle (PAT)

Appearance:

- (Poor tone, unfocused gaze, weak cry, decreased responsiveness to caretakers or painful procedures) may be indicators of decreased cerebral perfusion. (7)

Breathing:

- Depressed respiration due to depressed mental status.

- Respiratory distress:

- Obstructive shock (Tension pneumothorax, Cardiac tamponade, and Massive pulmonary embolism)

- Cardiogenic shock: Ductal-dependent congenital heart disease [8-10].

Circulation:

- Poor perfusion

- Skin temperature, mottled or cool.

- Capillary refill > 2 seconds suggests shock.

- Flash capillary refill (<1 second) may be present.

- Heart rate: Tachycardia

- Decreased intensity of distal pulses in comparison to central pulses

- Bounding pulses may be present. [11-13]

Physical examination

**Vital signs: Respiratory rate, Heart rate, Temperature, Blood pressure

Chest

- Stridor, wheezing, or abnormal breath sounds: anaphylaxis.

- crackles may have a pneumonia (septic shock) or heart failure (cardiogenic shock)

- asymmetric breath sounds: tension pneumothorax [14-17]

CVS

- Distended neck veins in heart failure, or cardiac tamponade or tension pneumo- or hemothorax.

- Murmurs or a gallop rhythm: heart failure and cardiogenic shock.

- Muffled heart tones: cardiac tamponade.

Pulse differential: coarctation of the aorta [18,19]

Abdomen

- Hepatomegaly: heart failure, cardiogenic shock.

- Abnormal skin findings:

- Urticaria or facial edema suggests anaphylaxis.

- Purpura can be seen with septic shock.

- Bruises and/or abrasions may be noted with trauma [20,21].

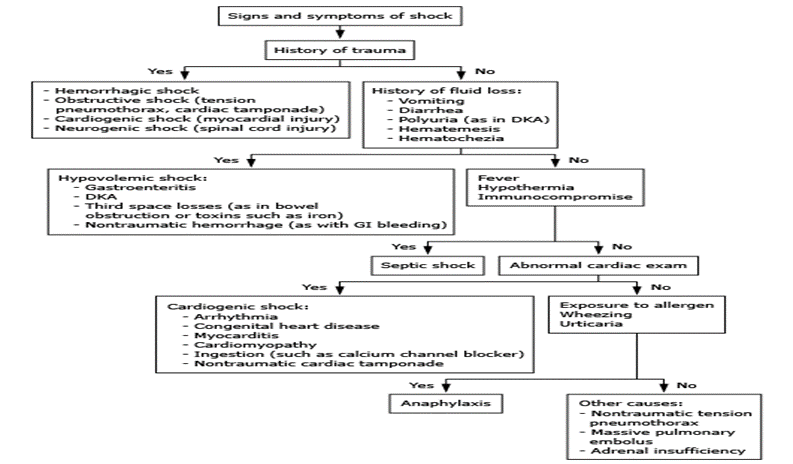

Approach to the classification of undifferentiated shock in children [22]

Sepsis definitions:

- Sepsis: SIRS in the presence of suspected or proven infection [23].

- Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS):

The presence of at least 2 of the following 4 criteria, one of which must be abnormal temperature or leucocyte count:

- Core temperature of >38.5°C or <36°C.

- Leucocyte count elevated or depressed for age

- Tachycardia, or bradycardia

- Mean respiratory rate increased or decreased from normal [24-27]

- Septic shock: Sepsis and cardiovascular organ dysfunction [28]

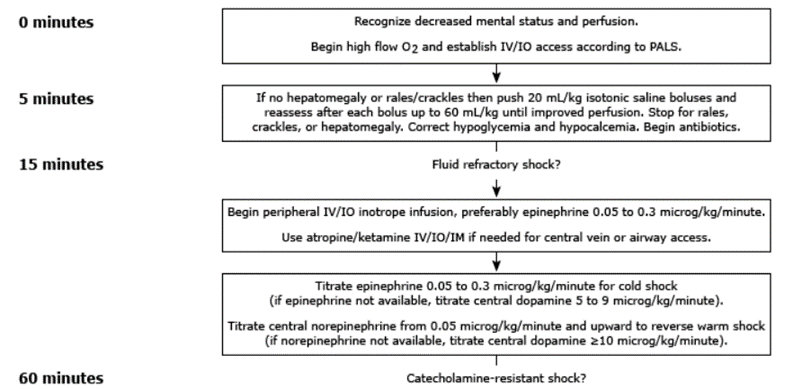

Septic shock: initial resuscitation (first hour)

- In the first hour of resuscitation, the goals are to maintain: Airway, breathing and Circulation [29]

- Obtain vascular access (IV or intraosseous [IO]) within 5 minutes

- Start appropriate fluid resuscitation within 30 minutes

- Begin broad-spectrum antibiotics within 60 minutes

- For patients with fluid-refractory shock, initiate peripheral or central inotropic infusion within 60 minutes [30-33]

Airway and breathing:

- 100 percent oxygen, titrated to avoid SpO2 >97 percent.

- Rapid sequence intubation (RSI) if needed to protect the airway, [34,35]

Common used inotropes:

1- Epinephrine (adrenaline): (0.05 to 0.1 mcg/kg/minute, up to 1.5 mcg/kg/minute)

- The most common used inotrope, used in septic shock, anaphylactic shock, asystolic arrest.

- S/E: Constriction of renal and splanchnic vesssels, Tachyarrhythmias, Hyperglycaemia [36]

2- Norepinephrine (noradrenaline):(0.01 - 0.1 mcg/kg/minute) up to 1 – 2 mcg/kg/min

- Used alone in septic shock or with epinephrine in cases of resistant shock requiring high dose epinephrine

- S/E: Bradycardia, reducing tissue perfusion [37]

3- Dopamine: 3–20mcg/kg/min

- Used n septic shock if epinephrine and epinephrine not available

- S/E: tachyarrhythmias, and pulmonary vasoconstriction

- It can give prepherally in small dose if central line not available [37-39]

Less commonly used inotropes

4-Dobutamine: 5–20mcg/kg/min

- Used in cardiogenic shock

- S/E: Tachyarrhythmia, hypotension due to peripheral vasodilatation (39)

5-Milrinone: 0.25–1mcg/kg/min

- Used in cardiogenic shock or low cardiac output state following cardiopulmonary bypass

- S/E: Arrhythmias, Hypotension, thrombocytopenia [40].

6-Vasopressin: 0.02–0.09U/kg/h

- Used in in children with septic shock who require high-dose catecholamines

- Side effects: splanchnic and peripheral ischaemia due to severe vasoconstriction [41].

laboratory studies for children with sepsis and septic shock:

- Rapid blood glucose

- Arterial or venous blood gas

- Complete blood count with differential

- Blood lactate

- Blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine

- serum electrolytes

- LFT

- PT, INR and APTT

- Fibrinogen and D-dimer

- Blood culture urine culture csf culture

- Other cultures as indicated by clinical findings

- Inflammatory biomarkers (eg, C-reactive protein, procalcitonin) [42-44]

Goal-targeted therapy for septic shock [45]

Discussion

Therapeutic endpoints of septic shock:

- Quality of central and peripheral pulses (strong, distal pulses equal to central pulses)

- Skin perfusion (warm, with capillary refill <2 seconds)

- Mental status (normal mental status) [46]

- Urine output (≥1 mL/kg/hour)

- Blood pressure (systolic pressure at least fifth percentile for age): 60 mmHg <1 month of age, 70 mmHg + [2 x age in years] in children 1 month to 10 years of age, 90 mmHg in children 10 years of age or older) [47]

- Normal serum lactate (eg, <2 mmol/L)

1. Emerging Issues

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) was defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in 2020 as a patient younger than 21 years of age with fever for more than 24 hours, laboratory evidence of inflammation and multisystem organ involvement without alternative plausible diagnosis, and a recent or current SARS-CoV-2 infection.84,85 Consider the diagnosis in patients with a Kawasaki-like illness, toxic shock syndrome, or macrophage activation syndrome. Hypotension was present in 80% of MIS-C cases reported as of October 2020, and 60% to 80% of patients required ICU admission due to shock requiring vasopressor support [47].

Obtain a C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, D-dimer, fibrinogen, procalcitonin, lactate dehydrogenase, and SARS-Cov-2 antibody or antigen screening as part of the workup.

Treatment includes immune-suppression under the guidance of specialists, including cardiology, infectious disease, and rheumatology. Reported complications are coronary artery aneurysms in 10% to 20% of cases, coagulopathy abnormalities, and a 1% to 2% mortality.85 ECLS has been used for a miniscule number of COVID-19 or MIS-C patients with varying levels of success, but there are insufficient data to determine its efficacy [48].

2. Disposition

Almost all pediatric shock patients require admission, usually to the PICU. Septic pediatric patients should be transferred to a tertiary care center with pediatric intensivists.

In the case of resolved anaphylactic shock, otherwise healthy patients who remain symptom free can be discharged after observation, although a specific disposition time has not been clearly established. One hour of observation incurs a 5% chance of biphasic reaction out-of-hospital, while six hours of observation may reduce that risk to 3%.86 Disposition also should consider the child’s family, transportation needs, and the ability for the family to accommodate specific pediatric needs [48].

While free-standing and critical access EDs have provided easier access to care, pediatric patient transfers have been increasing over time.1 To that end, having specialized pediatric transport systems in place has been shown to improve safety, decrease unplanned adverse events, and lower mortality.87-89 Ensuring that the transport team is composed of a physician, well-experienced nurses, paramedics, and possibly respiratory therapists, and that transport vehicles are equipped with all essential equipment is vital. It also is important to understand that during transport, patients are at increased risk for hypothermia and hypoglycemia; thus, having IV access is imperative [49].

Management of hypovolemic shock:

Goal:

Restore circulating volume and tissue perfusion, correct the cause

- Assess airway, administer oxygen and Establish IV access

- Fluid bolus of 20ml/kg isotonic fluid given over 5-10 minutes, continue fluid boluses until perfusion improves or hepatomegaly develops [49]

- In case of shock refractory to fluids, should be evaluated for ongoing blood loss or other causes of shock.

- Correct hypoglycemia and electrolytes disturbance if present [49]

- Vasoactive medications have no place in the treatment of isolated hypovolemic shock [50]

Management of cardiogenic shock:

- Assess airway, administer oxygen/mechanical ventilation, IV access

- A smaller isotonic crystalloid fluid bolus of 5 to 10 mL/kg, over 10 to 20 minutes

- Treatment with dobutamine or phosphodiesterase enzyme inhibitors can improve myocardial contractility and reduce systemic vascular resistance (afterload)

- Cardiac arrhythmias (eg, supraventricular or ventricular tachycardia) should be addressed prior to fluid resuscitation [51]

Management of anaphylactic shock:

- The first and most important therapy in anaphylaxis is epinephrine. There are NO absolute contraindications to epinephrine in the setting of anaphylaxis.

- Airway: Immediate intubation if evidence of impending airway obstruction from angioedema. Intubation can be difficult and should be performed by the most experienced clinician available or by anesthesia doctor, give 100% oxygen.

- IM epinephrine (1 mg/mL preparation = 1:1000 solution): Epinephrine 0.01 mL/kg should be injected intramuscularly in the mid-outer thigh. injection can be repeated in 5 to 15 minutes (or more frequently). If no response after three injections prepares IV epinephrine for infusion.

- Place patient in recumbent position, if tolerated, and elevate lower extremities.

- Normal saline rapid bolus: 20 mL/kg.

- Albuterol: For bronchospasm resistant to IM epinephrine, give albuterol 0.15 mg/kg (minimum dose: 2.5 mg) in 3 mL saline inhaled via nebulizer. Repeat, as needed.

- H1 antihistamine: Consider giving diphenhydramine 1 mg/kg (max 40 mg) IV.

- Glucocorticoid: Consider giving methylprednisolone 1 mg/kg (max 125 mg) IV [52].

Management of neurogenic shock:

- Intravenous fluids, and pharmacologic vasopressors as needed.

- Bradycardia caused by cervical spinal cord or high thoracic spinal cord disruption may require external pacing or administration of atropine.

- Correct hypothermia,

- Observe and prevent DVT (due to peripheral pooling of blood) [53]

Management of obstructive shock:

- Assess airway, administer oxygen/mechanical ventilation, IV access [53]

- Causes of obstructive shock (eg, tension pneumothorax, cardiac tamponade, hemothorax, pulmonary embolism, or ductal-dependent congenital heart defects) require specific interventions to relieve the obstruction to blood flow [53].

Conclusion

The management of children with shock is challenging. Some pitfalls include:

- If peripheral line is difficult, don’t waste time in multiple trials, don’t try for central line insertion, just insert intraosseous access.

- Failure to recognize nonspecific signs of compensated shock (ie, unexplained tachycardia, abnormal mental status, or poor skin perfusion)

- Inadequate monitoring of response to treatment

- Inappropriate volume for fluid resuscitation (usually too little for children with sepsis or hypovolemic shock, but possibly too much for those with cardiogenic shock)

- Failure to reconsider possible causes of shock for children who are getting worse or not improving.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement: Not applicable.

Funding: This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest: All other authors report no conflicts of interest. Data Availability Data described in the manuscript, code book, and analytic code will be made available upon request pending application and approval.

References

- Thomovsky E, Johnson PA. Shock pathophysiology. Compend Contin Educ Vet, 2013; 35(8).

- Haifa Mtaweh, Erin V Trakas, Erik Su, Joseph A Carcillo, Rajesh K Aneja. Pediatr Clin North Am, 2013; 60(3): 641–654.

- Christopher W. Seymour, Matthew R. Rosengart JAMA, 2015; 314(7): 708–717.

- Kyuseok Kim, Han Sung Choi, Sung Phil Chung, Woon Young Kwon, Essentials of Shock Management, 2018: 55–79.

- Spronk PE, Zandstra DF, Ince C. Bench-to-bedside review: sepsis is a disease of the microcirculation. Crit Care, 2004; 8: 462–468.

- Rivers E, Nguyen B, Havstad S, Ressler J, Muzzin A, Knoblich B, et al. Early goal-directed therapy in the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med, 2001; 345: 1368–1377.

- Antonio Messina, Francesca Collino, Maurizio Cecconi. Fluid administration for acute circulatory dysfunction using basic monitoring. Ann Transl Med, 2020; 8(12): 788.

- Myburgh JA, Mythen MG. Resuscitation fluids. N Engl J Med, 2013; 369: 1243-1251.

- Cecconi M, De Backer D, Antonelli M, et al. Consensus on circulatory shock and hemodynamic Monitoring. Task force of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med, 2014; 40: 1795-1815.

- Monnet X, Marik PE, Teboul JL. Prediction of fluid responsiveness: an update. Ann Intensive Care, 2016; 6: 111.

- De Backer D, Biston P, Devriendt J, et al. Comparison of dopamine and norepinephrine in the Treatment of shock. N Engl J Med, 2010; 362: 779-789.

- Cecconi M, Hernandez G, Dunser M, et al. Fluid administration for acute circulatory dysfunction using basic monitoring: narrative review and expert panel recommendations from an ESICM task force. Intensive Care Med, 2019; 45: 21-32.

- Vincent JL, De Backer D. Circulatory shock. N Engl J Med, 2013; 369: 1726-1734.

- Berger T, Green J, Horeczko T, et al. Shock index and early recognition of sepsis in the emergency department: pilot study. West J Emerg Med, 2013; 14: 168-174.

- Tisherman Samuel A, Barie Philip, Bokhari Faran, Bonadies John, Daley Brian, Diebel Lawrence, et al. The Journal of Trauma: Injury, Infection, and Critical Care, 2004; 57(4): 898-912.

- Angus DC, van der Poll T. Severe sepsis and septic shock. N Engl J Med, 2013; 369(9): 840–851.

- Marik P, Bellomo R. A rational approach to fluid therapy in sepsis. Br J Anaesth, 2016; 116(3): 339–349.

- Dellinger RP, Levy MM, Rhodes A, Annane D, Gerlach H, Opal SM, et al. Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines Committee including the Pediatric Subgroup. Crit Care Med, 2013; 41(2): 580-637.

- Goldstein B, Giroir B, Randolph A. International pediatric sepsis consensus conference: definitions for sepsis and organ dysfunction. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2005; 6(1): 2–8.

- Brierley J, Carcillo JA, Choong K, et al. Clinical practice parameters for hemodynamic support of pediatric and neonatal septic shock: 2007 update from the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med, 2009; 37(2): 666–688.

- Kaplan JM, Wong HR. Biomarker discovery and development in pediatric critical care medicine. Pediatr Crit Care Med, 2010.

- Rey C, Los Arcos M, Concha A, et al. Procalcitonin and C-reactive protein as markers of systemic Inflammatory response syndrome severity in critically ill children. Intensive Care Med, 2007; 33(3): 477–484.

- Osamu Nishida, et al. The Japanese Clinical Practice Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock. 2016 (J‐SSCG 2016) Acute Med Surg, 2018; 5(1): 3–89.

- Gustavo A Ospina-Tascón, Luis E Calderón-Tapia. Inodilators in septic shock: should these be used? Ann Transl Med, 2020; 8(12): 796.

- Rui Shi, Olfa Hamzaoui, Nello De Vita, Xavier Monnet, Jean-Louis Teboul. Vasopressors in septic shock: which, when, and how much? Ann Transl Med, 2020; 8(12): 794.

- Olga N Kislitsina, Jonathan D Rich, Jane E Wilcox, Duc T Pham, Andrei Churyla, et al. Esther B Vorovich, Shock – Classification and Pathophysiological Principles of Therapeutics. Curr Cardiol Rev, 2019; 15(2): 102–113.

- Sacha Pollard, Stephanie B Edwin, Cesar Alaniz. Vasopressor and Inotropic Management of Patients with Septic Shock. P T, 2015; 40(7): 438-442, 449-450.

- Olivier Lesur, Eugénie Delile, Pierre Asfar, Peter Radermacher. Hemodynamic support in the early phase of septic shock: a review of challenges and unanswered questions. Ann Intensive Care, 2018; 8: 102.

- de Oliveira CF, de Oliveira DSF, Gottschald AFC, Moura JDG, Costa GA, Ventura AC, et al. ACCM/PALS haemodynamic support guidelines for paediatric septic shock: an outcomes comparison with and without monitoring central venous oxygen saturation. Intensive Care Med, 2008; 34(6): 1065–1075.

- Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, et al. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive Care Med, 2017; 18: 1–74.

- Ranjit S, Natraj R, Kandath SK, Kissoon N, Ramakrishnan B, Marik PE. Early norepinephrine decreases fluid and ventilatory requirements in pediatric vasodilatory septic shock. Indian J Crit Care Med, 2016; 20(10): 561–569.

- Thomas Standl, Thorsten Annecke, Ingolf Cascorbi, Axel R. Heller, Anton Sabashnikov, Wolfram Teske. The Nomenclature, Definition and Distinction of Types of Shock. Dtsch Arztebl Int, 2018; 115(45): 757–768.

- Jon Gitz Holler, Helene Kildegaard Jensen, Daniel Pilsgaard Henriksen, Lars Melholt Rasmussen, Søren Mikkelsen, Court Pedersen. Etiology of Shock in the Emergency Department: A 12-Year Population-Based Cohort Study. Shock, 2019; 51(1): 60–67.

- Molly Rideout, William Raszka. Hypovolemic Shock in a Child: A Pediatric Simulation Case. MedEdPORTAL, 2018; 14: 10694.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the management of common childhood illnesses. Pocket book of hospital care for children. 2nd ed. WHO; 2013.

- Møller MH, Claudius C, Junttila E, Haney M, Oscarsson‐Tibblin A, Haavind A, et al. Scandinavian SSAI clinical practice guideline on choice of first‐line vasopressor for patients with acute circulatory failure, Acta Anaesthesiol Scand, 2016; 60(10): 1347–1366.

- Emmanuel Ademola Anigilaje. Management of Diarrhoeal Dehydration in Childhood: A Review for Clinicians in Developing Countries. Front Pediatr, 2018; 6: 28.

- Marie Dam Lauridsen, Henrik Gammelager, Morten Schmidt, Henrik Nielsen, Christian Fynbo Christiansen. Positive predictive value of International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, diagnosis codes for and septic shock in the Danish National Patient Registry, BMC Med Res Methodol, 2015; 15: 23.

- Donat R Spahn, Bertil Bouillon, Vladimir Cerny, Jacques Duranteau, Daniela,Filipescu, Beverley J Hunt, et al. The European guideline on management of major bleeding and coagulopathy following trauma: fifth edition. Crit Care, 2019; 23: 98.

- Kleinman ME, Chameides L, Schexnayder SM. Part 14: pediatric advanced life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation, 2010; 122(18 Suppl 3): S876–S908.

- Kiguli S, Akech SO, Mtove G. WHO guidelines on fluid resuscitation in children: missing the FEAST data. BMJ, 2014; 348: f7003.

- Gutierrez G, Reines HD, Wulf-Gutierrez ME. Clinical review: hemorrhagic shock. Crit Care, 2004; 8(5): 373–381.

- World Health Organization; Geneva: Pocket book of hospital care for children: guidelines for the management of common illnesses with limited resource, 2005.

- Daniel LoVerde, Onyinye I. Iweala, Ariana Eginli, Guha Krishnaswamy. Anaphylaxis. Chest, 2018; 153(2): 528–543.

- Alberto Alvarez-Perea, Luciana Kase Tanno, María L. Baeza. How to manage anaphylaxis in primary care. Clin Transl Allergy, 2017; 7: 45.

- Athamaica Ruiz Oropeza, Annmarie Lassen, Susanne Halken, Carsten Bindslev-Jensen, Charlotte G Mortz. Anaphylaxis in an emergency care setting: a one-year prospective study in children and adults. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med, 2017; 25: 111.

- F Estelle R Simons, Ledit RF Ardusso, M Beatrice Bilò, Victoria Cardona, Motohiro Ebisawa, Yehia M El-Gamal, et al. International consensus on (ICON) anaphylaxis. World Allergy Organ J, 2014; 7(1): 9.

- Estelle R Simons, Motohiro Ebisawa, Mario Sanchez-Borges, Bernard Y Thong, Margitta Worm, Luciana Kase Tanno, et al. 2015 update of the evidence base: World Allergy Organization anaphylaxis guidelines. World Allergy Organ J, 2015; 8: 32.

- Reynolds HR, Hochman JS. Cardiogenic shock. Current concepts and improving outcomes. Circulation, 2008; 117: 686–697.

- Olivier Brissaud, Astrid Botte, Gilles Cambonie, Stéphane Dauger, Laure de Saint Blanquat, Philippe Durand, et al. Experts’ recommendations for the management of cardiogenic shock in children. Ann Intensive Care, 2016; 6: 14.

- Alexander G Truesdell, Behnam Tehrani, Ramesh Singh, Shashank Desai, Patricia Saulino, Scott Barnett, et al. ‘Combat’ Approach to Cardiogenic Shock. Interv Cardiol, 2018; 13(2): 81–86.

- Ovidiu Chioncel, Sean P Collins, Andrew P Ambrosy, Peter S Pang, Razvan I Radu, Ali Ahmed, et al. “Therapeutic Advances in the Management of Cardiogenic Shock”. Am J Ther, 2019; 26(2): e234–e247.

- Ashish H. Shah, Rishi Puri, Ankur Kalra. Management of cardiogenic shock complicating acute myocardial infarction: A review Clin Cardiol, 2019; 42(4): 484–493.