Status and Constraints Evaluation of Artificial Insemination in Bishoftu and its Environs

Koku Abeb1 and Tesfaye Belachew2,*

1Assela Regional Animal Health Diagnostic Laboratory, Assela, Oromiya, Ethiopia

2Jimma University college of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine

Received Date: 10/11/2022; Published Date: 28/11/2022

*Corresponding author: Tesfaye Belachew, Jimma University college of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine, Ethiopia

Abstract

Efficiency of artificial insemination service might be lower due to various challenges including poor estrus detection, inefficiency of artificial insemination techniques, and distance from AI station, poor management system, inadequate nutrition and poor quality of semen. Failure of estrus detection and improper timing of insemination has been the most known problems of in diary animals. The intention of this study was to appraise the status, challenges and the outcome.AI service beneficiaries in and around bishoftu town. In this study, a total of 287 respondents (smallholder farmers, dairy farm, Animal’s health professionals and Artificial Insemination Techniques) were included through structured questionnaires survey and interviewed. In to this, Retrospective data study was included in the study to evaluate the status of AI service in the study site. As the result revealed that from 269 total farmer respondents 49.1% (132/269) had got AI service on time without any interruption while 50.9 % (137/269) AI users couldn’t get service on time due to lack of input, unavailability of AITs and discontinuation of service on weekends and holidays with statistically significant among kebeles (p<0.05). Bellowing, clear mucous discharge from vagina, mounting, decrease production and feed intake, restlessness and nervousness, were found to be the most common estrus manifestation observed by diary owners as holidays, lack of appropriate collaboration and communication among stake holders, and repeat breeding. In case of repeat breeding, he maximum and minimum impression of AI users toward using AI repeatedly were 43.8% (Danbi) and 33.0%(Kality) respectively with statistically insignificant among respondents (p>0.05). Generally, the questionnaire survey indicated that the application of assisted reproductive biotechnologies in the study area was at infant stage surrounded with challenge full so it requires urgent involvement of stakeholders before it aggravates.

Keywords: Artificial Insemination; Semen; Dairy farm

List of Abbrevations: AHPs: Animal Health and production Professional; AI: Artificial Insemination; AITs: Artificial Insemination Technicians; ART: Assisted Reproductive Technology; BVD: Bovine Viral diarrhea; CL: Corpus Luteum; CR: Conception Rate; CSA: Central Statistics Agency; DADIS: Domestic Animal Diversity Information System; DAGRIS: Domestic Animal Genetic Resource Information System; EASE: Ethiopian Agricultural Sample Enumeration; EIBC: Ethiopian Institute of Biodiversity Conservation; IBR: Infectious Bovine Rhinotrachitis; ILRI: International Livestock Research Institute; LN: Liquid Nitrogen; NAIC: National Artificial Insemination Center; OIE: Office of International des Epzooties; PG: Prostaglandin; PGF2a: Prostaglandin F2 a; SARI: Southern Agriculture Research Institute; SIDA: Swedish International Development Agency; TNAU: Tamil Nadu Agricultural University

Introduction

Artificial Insemination (AI) is the manual placement of semen in the reproductive tract of the female by a method other than natural mating and it is among the group of technologies commonly known as assisted reproduction technologies (ART), whereby offspring are generated by facilitating the meeting of male and female gametes (Jemal, 2014). Since the early attempts by Italian physiologist Spallanzani, there has been considerable effort in the development of semen preservation and AI technology (Katherine and Maxwell, 2006). At present, fresh, chilled and frozen-thawed semen are used extensively for AI in animal breeding and production throughout the world (Ball and Peters, 2004). Selective breeding has been considered as one of the highly effective and sustainable approaches for increasing animal productivity in the long-term. In this regard, AI allows a single animal to have multiple progenies, reducing the number of parent animals required and allowing for significant increases in the intensity of selection, and proportional increases in genetic improvement. Improvement in livestock resources can be achieved through the implementation of an efficient and reliable AI service, concomitantly with proper feeding, health care and management of livestock. Hence crossbred cattle, the progeny of zebu and Holstein Frisian/jersey cattle are mainly used for milk production in this country which is concentrated in dairy farms around the major cities (Belihu, 2002; Hassen et al., 2007).

In Ethiopia, AI was introduced in 1938 in Asmara, then part of Ethiopia, which was interrupted due to the Second World War and restarted in 1952. It was again discontinued due to unaffordable expenses of importing semen, liquid nitrogen and other related inputs requirement. In 1967 an independent service was started in the Arsi Region, Chilalo Awraja under the Swedish International Development Agency (SIDA). The technology of AI for cattle has been introduced at the farm level in the country over 35 years ago as a tool of genetic improvement (Zewdie et al., 2006). Thus, AI has become one of the most important techniques ever devised for the genetic improvement of farm animals. It has been most widely used for breeding dairy cattle and has been made bulls of high genetic merit available to all (Jodie, 2006 and Lobago, 2007).

The total cattle population of Ethiopia is estimated to be about 56.71 million. Out of this total cattle population, the female cattle constitute about 55.45 percent and the remaining 44.55 percent are male cattle (CSA, 2007/14/15). On the other hand, the results obtained indicated that 98.66 percent of the total cattle in the country are local breeds. The remaining are hybrid and exotic breeds that accounted for about 676,748 (1.19%) and 80,939 (0.14%), respectively. The total number of both exotic and hybrid female cattle produced through the crossbreeding work for many decades in the country are quite insignificant indicating unsuccessful crossbreeding work. Ethiopia needs to work hard on improving the work of productive and reproductive performance improvements of cattle through appropriate breeding and related activities (Gebremedhin, 2008). Achieving increased milk and meat production through genetic improvement of indigenous cattle have been the primary goals of the livestock development plan of Ethiopia. Paradoxically, though AI program continued for several decades, the genetic improvement achieved to date is very unsatisfactory due to several factors such as poor heat detection, inefficient AI delivery system, and poor semen quality are known major causes of poor success of AI programs (Salverson and Perry, 2005; Demeke, 2010; Jemal, 2014).

Although, AI was introduced long years ago in the country, it is still unsuccessfully performing, due to technical, system related, financial and managerial problems. Among the technical constraints; poor heat detection, communication and transport problems that hamper timely insemination, poor semen processing and storage technology affecting semen quality, and inefficiency of AI technicians (Belihu, 2002; Tadesse et al., 2010). The present study was, therefore, aimed to assess the ongoing status of AI service, and associated challenge in the study area and to come up with applicable and workable recommendations that could call upon decision makers and stakeholders to give the most attention to the genetic improvement and productivity of the sector.

Materials and Methods

Description of Study Area

The study was conducted from November, 2015 to April, 2016 in urban and rural small holder farmers and dairy farms in and around Bishoftu town, East showa zone, Oromiya regional state. Bishoftu town is located in 47 km along south east of Addis Ababa; at 90 N latitude and 400 E longitudes; an altitude ranging 1500-2250 meters above sea level (m.a.s.1); the mean monthly minimum and maximum air temperature ranged from 11.2-13.5 C0 and 21.6-31.5 C0 respectively. The area has rainy seasons; the minor one extending from February to April and the major one between June and September. The average annual rain fall is about 877.2 mm. the mixed crop livestock production is the predominate production system in which Teff (Eragrostis teff) and wheat are the main crops cultivated, plus, especially chickpea is grown in the bottomlands and residual moisture in selected areas (ILRI, 2005). In addition to farming system there are large, medium and small-scale dairy farms are found in and around the town. The study area was purposively selected because it was believed that this area is the one where artificial insemination service is widely exercised.

Study Population

Artificial Insemination (AI) personnel, animal health and production professionals (AHPPs) in Bishoftu town, Ada’a district livestock and Fisheries Development Office and dairy farmers were represented in the study population. In addition to these, retrospective data was obtained from AI certificates and inseminator’s recording book.

Study Design and Sampling Procedure

A cross-sectional type of study supported by questionnaire survey was carried out from November, 2015 to April, 2016 in urban and rural; smallholder’s farmers and dairy farms in and around Bishoftu town; East showa zone, Oromiya regional state. Structured questionnaire survey format (Annex: 1 & 2) was used to collect data from 287 respondents (269 smallholders’ farmers, dairy farms and 18 animal health professional and Artificial insemination technicians) were asked accordingly. Challenge they faced was identified and evaluated after are provided with questionnaire survey format and interviewed.

In the retrospective study, data were collected from records of AI service covering the period from 2004- April 2008 E.C. Artificial Insemination records were obtained from the district record books. The number of cattle inseminated, synchronized and conceive were included during the retrospective study.

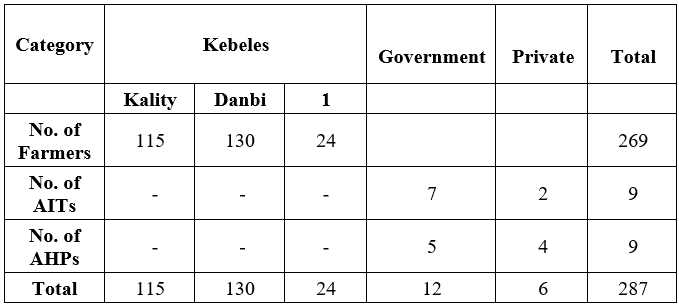

In the sampling procedure, three kebeles, which are major users of Artificial Insemination service in and around Bishoftu, were purposively selected to conduct the study. Smallholder farmers and dairy farms were selected using sample random sampling. A total of 269 smallholder farmers and dairy farms owners were randomly selected from smallholder, medium and large-scale dairy farm Kality, Danbi and 01 Kebeles(table)

Table 1: Distribution of Farmers, AITs and AHPs in the study site.

Statistical Analysis

All data were entered in the Microsoft excel after collection of data respondents in the study area. Then the analysis work done using SPSS version 16. The data was summarized using descriptive statistics such a chi-square, frequency in order to assess the magnitude of the difference of comparable variables.

Results

Status of the conventional AI delivery system

In study site there were three Artificial Insemination station and mobile service for the whole Ada’a district AI users. The Artificial insemination program is both government and private running activity; which is currently under the control of Ministry of Livestock’s and Fisheries Development Office that was shifted from ministry of Agriculture in this year. Semen and liquid nitrogen mainly were procured from Kality National Artificial Insemination center and few dairy farm owner import semen from other countries. Kality located within Addis Ababa sub-site which 30km far from Bishoftu town. Animals showing estrus were inseminated at the station and the farm by mobile inseminator. Artificial Insemination service costs about 30birr insemination by government while private inseminators were costing about 60-200birr/ insemination depend on breed type of the semen. Additionally, there was natural mating service charged around 100 birr per service. The type of semen was mainly selected by inseminator and concerned bodies. Observation of estrus sings and bringing the animals for artificial insemination solely rests on the owners. The pregnancy diagnosis was done on the three months after insemination by technician diagnosis and owner reports.

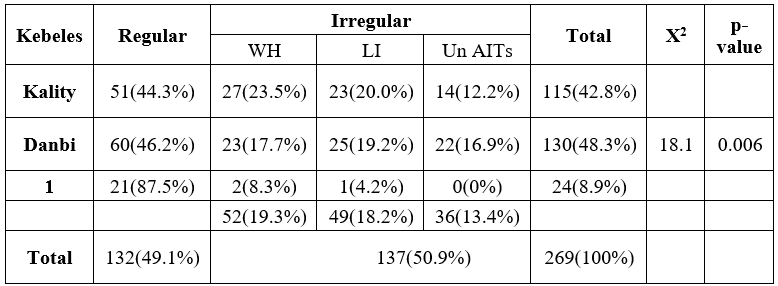

Results of Questionnaires of the farmers

Results of smallholder farmers and dairy farms questionnaires survey indicate that among 269 of owners 132 (49.1%) have got service regularly without any interruption while other respondents 137 (50.9%) couldn’t get artificial insemination service regularly due to lack of inputs 13.4% (n=36), unavailability of AITs 18.2% (n=49) and discontinuation of service on weekends and holidays 19.3% (n=52) with statistically significance among kebeles (p<0.05). (Table 2:).

Table 2: Showing status of Artificial Insemination service in the study area.

Key: WH+= Weekends and Holidays service, Un AITs= unavailability AI technicians, LI= Lack of input

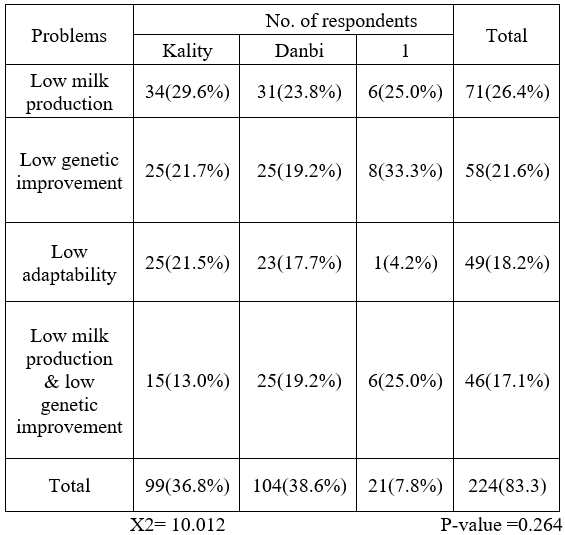

According to response of respondent of questionnaire survey revealed that around 83.3% identified the problems inbreeding in the study area. The minimum and maximum respondent’s perception about inbreeding problems were 7.8% in 01 and 38.6% in Danbi kebeles respectively. Which is statistically insignificant among kebeles (p>0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3: Showing perception of respondents about problems of inbreeding.

Almost all the respondents were known practically important estrus sign about 23.0% of owners detect their cows by observing bellowing, 22.3% clear mucus discharge from vagina, 19.7% mounting, 10% vaginal mucus discharge, 7.8% restlessness and nervousness, 7.1% redness of vulva, 5.2% decrease production and 4.1% decrease in feed intake with statistically significant among the owners (p<0.05). In relation to the above, 55.4% of respondents call AITs by mobile phone insemination, 37.2% of respondents go to AI station while other 7.4% were visited by technicians with statistically significant among kebeles (p<0.05). about 61.3% of respondents were inseminated their cows, when cow shows heat sign in the morning would be inseminated in the same day afternoon and when heat sign was seen afternoon cow would be inseminated in the next day morning; 30.1% of respondents confirmed that they wait the order of technician.

There were repeat breeding problem ranging up to five times in the area; when they face repeat breeding, they use artificial insemination service repeatedly (38.3%) while 43.5% use AI and natural mating and 18.2% used natural mating. In case of repeat breeding, the maximum perception of AI users toward using AI repeatedly is recorded in the Danbi kebele (43.8%) while the minimum was in Kality (33.0%) with statistically insignificant (p>0.05). from one hundred forty-eight unsatisfied owners 40.5% passed the date without breeding from both AI and natural mating and 32% use natural mating and waiting the next cycle to use AI service with statistically significant (p<0.05) difference was found among owners. In other hand from 121 satisfied farmers 4.5% passed the date without breeding the cow from AI and natural mating and waiting the next cycle to use AI service.

As the questionnaire survey of fifty-six-point one percent of farmers revealed that they had the awareness of semen type selection while forty-three-point nine percent had no select the semen they had used. About 49(18.2%) of them used breed type as criteria of selection both breed type and milk production with statistically significant among the kebeles (p<0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4: Shows Awareness of Respondents about Semen type.

Forty-point five percent of the farmers said that they do not have easy access to animal health service while fifty-nine-point five percent said that they more or less get the service nearby area. In relation to this the questionnaire survey of farmers indicated that 66.5% of the farmers said that they often have herd health problems, which directly and indirectly have impact on the efficiency of the artificial insemination service and productivity of the herd. According to he owners the disease that have the major importance in their herd were reproductive d (abortion, dystocia and calve death ) 8.9%, Mastitis 12.3%, conception failure 20.1% and other disease 28.5% with statistically significant among study sites. Result also indicated that from total of two hundreds sixty nine respondents forty five percent of them confirm that they were satisfied while fifty five percent of them were unsatisfied with the overall AI service due to varies reasons such as conception failure, unavailability of AITs, repeat breeding, long distance from animal health clinic and AI station, the discontinuous of AI service on holidays and weekends, varies diseases that affect the success of AI service and way of communication with AITs were major problems that cause un satisfaction on the site.

Result of Questionnaires of the AITs and AHPs

Result of questionnaires survey of the Artificial Insemination Technician (AITs) indicated that six (66.7%0 of the AITs had been trained at Assella whereas the rest three (33.33%) of them had been trained at kality and the length of training as well as the year they were attended the artificial insemination courses varied. Five (55.6%) of the artificial insemination technicians evaluated the quality of training as good while four (44.4%) of them evaluated the training as very good. Nine of them confirmed that they started as AITs career after 1996 E.C. five (55.5%) of artificial insemination technicians were giving services on the weekends and holidays depends on personal agreements; 11.1% (n=1) was giving service same times based on own his own interest while 33.3%(n=3) did not give service on the weekends and holidays. All of the artificial insemination technicians believe that National Artificial Insemination Center (NAIC) is carried out its responsibility correctly. Above half (55.6%) of AITs revealed that they get a little support from the district Livestock’s and Fisheries Development office, nongovernmental organization (NGO) and different association.

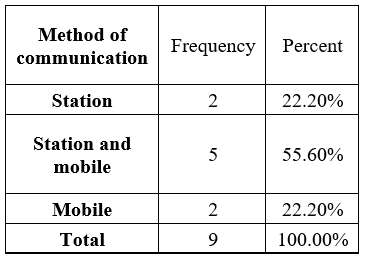

Among artificial insemination technicians five (55.6%) of them provide service both in station and mobile while 22.2% of them give services in station and 2(22.2%) of them delivery service in mobile only.

Table 5: Method of AITs delivering service to the beneficiary.

Four (44.4%) of the AITs cover the distance of 20-40 km, 22.2% (n=2) of them travel the distance of 6-10 km while the rest of artificial insemination technicians cover the distance of less than 5 km to deliver the service by using motorcycle 55.6% (n=4), Bajaj 11.1% (n=1) which is comfortable for transportation and the rest of them were not used means of transportation to deliver service. The average of cows being inseminated by artificial insemination technicians were 2-8 cows per day but all of AITs agreed that this range depends on the season of the year. Five (55.6%) had no other duties that affect their service while 44.4% (n=4) were had another responsibility besides the AI service.

All of the artificial insemination technicians were satisfied and happy as a technician but all of them agreed that there is less attention and incentive was given for the service. Six (66.7%) of AITs were taken the semen from Kality while 33.7 % of them were taken from Kality and Alpes. Types of semen selected by artificial insemination technicians and concerned bodies. The most of AITs were agreed on the following problems; shortage of AITs, reproductive disease, silent heat, lack of infrastructure, improper heat detection, lack of community awareness, repeat breeding and low payment per service. The most obvious heat sign that have practical importance used by AITs were clear mucous vaginal discharge 44.4% (n=4), bellowing 22.2% (n=2), mounting 22.2% (n=2) and decrease production and feed intake 11.1% (n=1). Seven of AITs said that they checked for heat before they inseminated and two of them also checked for pregnancy. The most of the technicians revealed that cows that show heat early in the morning should be inseminated on the same day afternoon and other respondents indicated that cows should be inseminated based on am and pm rule.

Almost all animal health professional revealed that the efficiency of AI service in the study area is very low due to poor heat detection/insemination which poorly expressed estrus for different reasons including breed, nutrition, disease and climate, absence of service on weekends and holidays, shortage of AITs, inadequate inputs. Therefore, estrus passes without breeding (few would resort to natural service). Absence of legal framework for regulation of importation and distribution of semen, poor infrastructure for storage, handling and transportation of semen; lack of integration of AI service with livestock health and feed package, and absence of appropriate collaboration and communication between the National Artificial Insemination Center (NAIC), regional bureaus and other stake holders. Lack of proper breeding policy that control indiscriminate insemination/breeding, wrong selection of semen that leading to low genetic improvement, lack of motivation and on job training. These were some of service hinder constraints of side area.

Retrospective Data study result

Retrospective data of artificial insemination service of five years (2004-208 E.C) were accessed. Data were obtained from artificial insemination technicians (AITs) recording book and reports of each year. The data obtained indicates that were an increasing number of inseminated dairy cows in each year. Almost there is uniformly increment of calve born as the inseminated cow increased. In 2008 E.C a total of one thousand eight hundred and seventy-four (1874) cows were inseminated by conventional heat detection and four hundred fifty cows (450) were synchronized and three hundred cow show heat sign. Among synchronized cows one hundred eleven (111) were conceived but two hundred six (206) were didn’t conceived due to several reasons such as conception failure, poor semen quality, poor body condition, improper site of semen deposition and disease. In general, the result of retrospective data revealed that the AI service at this study area is still at its infant stage and it requires urgent measures to change the situation and to achieve a success.

Table 6: Retrospective data showing the number of dairy cows take AI covering from year (2004-2008 E.C).

Discussion

The study was conducted through questionnaire survey and interview of smallholder dairy farmers, animal’s health professionals and AITs to assess ongoing and constraints evaluation of AI service in and around Bishoftu town. The services were running both by government and private workers. The cost of one insemination was 30 birr and 60-200 birr were required payment by government and private inseminators to provide service respectively. This payment is much expensive to the beneficiaries comparing with the report of Jemal (2014) which was 2 birr/service.

The current study revealed 40.1% of AI users have got AI service on time without any interruption were as 50.9% of AI users have got AI service irregularly due to unavailability of service on weekends and holidays (19.3%), shortage of AITs (18.2%) and lack of input (13.4%). Data analysis showed statistically significant difference among kebeles (p<0.05). The current study with respect to sustainable and irregular AI service was in agreement with Nuraddis et al., (2014) who reported 41% and 59% respectively. Gebremadhin, (2008) reported higher than the current report and this may be due to difference in awareness and perception of users about AI among study. The current study revealed that the AI beneficiaries use natural mating (63%) when the service was discontinued due to different factors and postpone estrus time without breeding and waiting the next service (36.5%). These were the possible solutions taken by AI users and the absence of insemination this finding is greater than the result by Milkesa (2012) (20% & 78.6%) and Nuraddis et al., (2014) (22.1% & 77.9%) conducted at Ambo and Jimma zone respectively. This difference may be due to availability of selected bull used for natural mating among the study site.

There was a problem of repeat breeding bitterly mentioned by dairy owners that should be seriously addressed. A number of service/inseminations per animals is associated with poor semen quality and handling practice, lack of incentive to AITs and poor estrus detection Gebremedhin, (2008). Additionally, method of communication system, long distance traveling to AI station, lack of improvement in transportation, telecommunication and generally infrastructure make more serious challenge in avoiding repeat breeding. Efficiency of AITs and input for activity was also serious constraints for AI delivering system (Taddese, 2010).

As the result revealed that the major health problems in the study area were mastitis, reproductive health problems and other diseases with 32.9% which is in line with report of Milkesa (2012) (36.9%) while it is greater and lessthan the result of Nuraddis et al., (2014) (72.1%) and Haileyesus (2006) (9%) respectively. This variability could be attributed to differences in management system, breed and animal health prevention strategies among study area.

There was statistically significant difference (p<0.05) among the respondents in heat sign and about 23% of th dairy owners detect their dairy cows by observing bellowing, clear discharge from vagina (22.3%), mounting (19.7%), vagina mucous discharge (10%), restlessness and nervousness (7.8%), redness and swelling of vulva (7.1%), decrease production (5.2%) and decrease feed intake (4.1%). This result is in line with study result reported by Milkessa (2012) fore restlessness (3.1%) and mounting (16.9%) but less than the study result reported by Nuraddis et al., (2014) with 32.8% for mounting and vulva discharge (28.7%). This difference may be due to the awareness and knowledge of the owners toward it signs. The eighty-three-point three percent of respondents were had maximum perception toward in breeding problem with statistically insignificant (p<0.05) among dairy owners from problems of inbreeding mentioned by dairy farmers 25.3% for low milk production, low genetic improvments (20.8%), low adaptability (17.1%) and low genetic improvement and milk production (16.4%). This study result was agreed with the result reported by Nuraddis et al., (2014) (82%). This similarity may be due to the uniform perception and awareness of AI users.

The outcome of the study result of artificial insemination technicians regarding to the evaluation of the quality of the training (55.6%) of them evaluated as good whereas (44.4%) of them see as very good. This result revealed that the AITs didn’t get on job trainings; this shows that there is some deficit indicating a need for upgrading the capacity of technicians through giving proper trainings particularly for those who were under the category of good technical expertise. Six (66.67%) of technicians were attended their training at Asella whereas the rest of the technicians were attended at Kality. Among AI technicians 55.5% were given the AI service on the weekends and holidays based on the personal agreement, 11.1% was given service on his own interest and 33.3% of them didn’t deliver service. All most all of AI technicians were happy as technicians but all of them had agreed that less attention, incentive and motivation was given for them and to the service. This alarming result was in line with the reported by Gebremedhin (2008) and Nuraddis et al., (2014).

The study results obtained from animal health professionals indicate that almost all animal health professional revealed that the efficiency of AI service in the study area is very low due to absence of appropriate collaboration and communication between the National Artificial Insemination Center, regional bureaus and other stakeholders, lack of integrating AI service with livestock health and feed packages. These hinder the progression of AI service in the study area. This result is agreed with the results reported by Gebremedhin (2005) and Nuraddis et al., (2014).

The retrospective data result covering from year 2004- mid of 2008 E.C indicates that, as number of AI users increasing from year to year, the numbers of calves born in a similar way increasing in the relation to number of inseminated cows. Additionally, this retrospective result revealed that there was good commence of actual application of in heat induction with AI service simultaneously. Even though the numbers of AI users and calves born is increasing; the AI service at this study area is still at infant stage. This might be due to poor awareness AI users, poor quality of semen, management problem, inadequate infrastructure, shortage and efficiency of AITs.

The most outstanding challenge of AI service identified in this study area were poor heat detection/insemination which is poorly expressed estrus for different reasons including breed, nutrition, disease and climate; absence of service on weekends and holidays, shortage of AITs shortage of input, absence of legal framework for regulation of importation and distribution of semen, poor infrastructure for storage, handling and transportation of semen, lack of integration of AI service with livestock health and feed packages and absence of appropriate collaboration and communication between the National Artificial Insemination Center, regional bureaus and stakeholders, lack of proper breeding policy that control indiscriminate insemination, lack of motivation and on job training, problems, of repeat breeding, poor awareness creation in dairy farmers, health problems, ways of communication of dairy cattle owners with AITs. These findings are in agreement with the result reported by Gebremedhin (2005), Zewde (2007) and Zerihun et al., (2013).

Conclusion and Recommendations

This study was conducted to evaluate the status and challenge of AI service delivery in and around Bishoftu town. Although, wide range application of AI and its success throughout developed world for long period of time, it is still very infant in our country as general and specifically in study area. This is generally due to poor motivation and skills of inseminators, poor heat detection/insemination, conception failure/repeat breeding, managerial problems, lack of proper breeding policy, insufficient resource in terms of inputs and facilities. Among these the most important challenge associated with AI service in the study area including conception failure, repeat breeding, absence of collaboration and regular communication between AITs and stakeholders, and absence of incentive and reward to motivate AI technicians. The repeat breeding and reproductive health problems situation were a very knocking finding. Based on the above short conclusion the following recommendations were forwarded to address challenge of artificial insemination and to improve reproductive biotechnology application/implementation in study area:

- Station and mobile AI service delivery should be encouraged there need to be outreach service to increase the accessibility of AI to the small holder;

- The private sector should be highly encouraged to be involved in the AI service sector; to address door-to-door AI service;

- Awareness and training should be developed for farmers to enhance AI service and to avoid related constraints reproductive biotechnology

- AITs should have regular communication with dairy owner, animal health professionals, office of livestock and fisheries development and other stakeholders;

- Import sexed and desired quality of semen to improve genetic makeup and milk production of the sector

There should be strong relationship between AITs and animal health professional to address the prevailing reproductive health problems;

References

- Agegnehu B. Performance evaluation of semen production and distribution team for 2006/07 fiscal year. NAIC, Addis Ababa, 2007.

- Arthur GH. Arthur’s Veterinary Reproduction and Obstetrics 8th ed, 2007; 430-767.

- Azage T, Berhanu G, Dirk H. Livestock input Supply and Service Provision in Ethiopia, Challenges and Opportunities for Market-Oriented Development. IPMS, IRLI, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2010; pp.10-12.

- Ball PJH, Peters AR. Reproduction in cattle. 3rd ed, Fibiol, 2004; pp. 1-13.

- Bearden HJ, Fuquary JW. Applied Animal Reproduction. 5th Upper Saddle, New Jersey. Prentice Hall Inc, 2000; pp. 138-147.

- Bearden HJ, Fuquay JW, Willard ST. Applied Animal Reproduction. 6th Mississippi State University. Pearson, Prentice Hall. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey, 2004; 07458: pp. 155-233.

- Bekana M, Gizachew A, Regassa F. Reproductive Performance of Fogera Heifers Treated with Prostaglandin F2a for Synchronization of Estrus.Tropical Animal Health and Production, 2005; 37: 373-379.

- Belihu KD. Analysis of Dairy Cattle Breeding Practice in Selected Area of Ethiopia. PhD Thesis, Addis Ababa University, FVM, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia, 2002.

- Brito LFC, Silva AEDF, Rodrigues LH, Vieira FV, Deragon LAG, Kastelic JP. Effect of environmental factors, age and genotype on sperm production and semen quality in Bos indicus and Bos Taurus in Brazil. Animal Reproduction Science, 2002; 70: 181-190.

- Chatikobo P. Artificial Insemination in Rwanda. In: Exploring Opportunities, Overcoming Challenges, III, EADD, Rwanda, IRLI, Technoserve, ABSTCM and ICRAF, 2009.

- Connor M. Reviewing Artificial Insemination Technique. The Pennsylvania State University. ICT3420, 2013.

- CSA, Central Statistics Agency, Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia: Agricultural Sample Survey 2014/15, volume II, Report on livestock and livestock characteristics. Statistical Bulletin 578. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2015; pp. 9-10.

- Das HN, Verma RP, Ansari MR, Munjumdar AC. Assessing of the fertilizing potential in crossbreeding bulls by some current diagnostic approach invitro. Journal of Animal Sciences, 1999; 69: 27-31.

- Day ML. Animal Hormonal Induction of Estrous cycle in anestrous Bos Taurus Beef cows. Department of Animal Sciences, the Ohio State University, Reproduction Science, 2004; 82-83: 487-494.

- Demeke N. Study on the Efficiency of Conventional Semen Evaluation Procedure Employed at Kality National Artificial Insemination Center and Fertility of Frozen Thawed Semen. Msc Thesis, Addis Ababa University, FVM, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia, 2010.

- EASE, Ethiopian Agricultural Sample Enumeration: Statistical report on Farm Management Practice, livestock and farm implements part II. Results at the country level. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2003; pp. 219-232.

- FAO: A review of the Ethiopian dairy sector. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) _ Sub Regional Office for Easter Africa, by Zelalem Y., Emanuelle G. and Ameha S. Ethiopia, 2011; pp.20, 23, 24.

- Gebremedhin D. All in one: A Practical Guide to Dairy Farming. Agri-Service Ethiopia Printing Unit, Addis Ababa, 2005; pp. 15-21.

- Gebremedhin D. Assessment of Problems/Constraint Associated with Artificial Insemination Service in Ethiopia. Msc. Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Debre Zeit, Ethiopia, 2008.

- Gentry A. Pros and Cons of Artificial Insemination in Cattle, 2010.

- Hansen GR. Managing Bull Fertility in Beef Cattle Herds.Animal Science Department.Florida Cooperative, Extension, Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida, 2006.

- Hassen F, Bekele E, Ayalew W, Dessie T. Genetic Variability of five Indigenous Ethioipian Cattle breeds using rapid markers. African Journal of Biotechnology, 2007; 6(19): 2274-2279.

- Haugan T, Reksen O, Grohn YT, Kommisrud E, Ropstad E, Sehested E. Seasonal Effect of Semen Collection and Artificial Insemination on Dairy Cow Conception. Animal Reproduction Science, 2005; 90: 57-71.

- Heersche G. Benefits of Artificial Insemination and Estrus Synchronization of Dairy Heifers. Dairy Notes, University of Kentucky, 2002; pp 1-2.

- Holm DE, Thompson PN, Irons PC. The Economic effects of an estrus Syncronization Protocol using Prostaglandin in Beef Heifers. Theriogenology, 2008; 70: 1507-1515.

- Hunderra Evaluation of semen parameter in Ethiopia indigenous bulls kept at kalti, Artificial insemination center, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.Msc Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia, 2004; p.6-7,

- Hussen KA, Tegegne MY, Kurtu Gebremedhin. Traditional cow and camel milk production and marketing in agro-pastoral and mixed crop–livestock systems: The case of Mieso District, Oromiya Regional State, Ethiopia. IPMS (Improving Productivity and Market Success) of Ethiopian Farmers Project Working Paper 13. Nairobi, Kenya: International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), 2008.

- Ibrahim N, Hailu R, Mohammed A. Assessment of Problems Associated with Artificial Insemination Service in Selected Districts of Jimma Zone. Journal of Reproductive and Infertility, 2014; 5(2): 37-44.

- Ada’a Liben Wored Pilot Learning Site Diagnosis and Program Design in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2005; 63: 6-11.

- Israel GD. Determining Sample Size. University of Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agriculture Sciences, EDIS, 1992.

- Jane AP, Jamie EL, Rhonda CV. Estrous Synchronization in Cattle. Extension Service of Mississippi State University. Mississippi State University, 2011.

- Jemal H. Study on Factors Affecting the success of Artificial Insemination Program in Cattle, Silte Zone. Msc Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Debre Zeit, 2014.

- Jodie AP. Dairy Reproductive Management Using Artificial Insemination.11th University Arkansas. Cooperative Extension-Service, University of Arkansas Division of Agriculture, U.S. Department of Agriculture and country governments cooperating, 2006.

- Katherine MM, Maxwell WM. The Continued development of Artificial Insemination Technologies in in Alpacas. Center for Advanced Technologies in Animal Genetics and Reproduction the University of Sydney, Amonograph, 2006; pp.1-6.

- Lemma A. Factors Affecting the Effective Delivery of Artificial Insemination and Veterinary Service in Ethiopia: Addis Ababa University Presentation to the Ethiopian Fodder Roundtable on Effective Delivery of Input Services to Livestock Development. A Presentation Report, June /2010, Addis Ababa, 2010.

- Lobago F. Reproductive and Lactation Performance of Dairy Cattle in the Oromia Central Highlands of Ethiopia with Special Emphasis on Pregnancy Period.Doctoral thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, 2007; pp.19.

- Lucy MC, McDougall S, Nation DP. The use of hormonal Treatment to improve the reproductive Performance of Lactating dairy Cows in Feedlot or Pasture- based management systems. Animal Reproductive Science, 2004; 82-83: 495-512.

- Manafi M. Artificial Insemination in Farm Animals. 1st ed, 2011; p 153-166.

- Mekonnen T, Bekana M, Abayneh T. Reproductive Performance and Efficiency of Artificial Insemination Smallholder Dairy Cows/ Heifers in and around Arsi- Negelle, Ethiopia. Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Addis Ababa University, Livestock Research Forrural Development, 2010; 22:1-5.

- Morrell JM. Artificial Insemination. Current and Future Trends. Swedish University of Agriculture Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden: In Artificial Insemination in Farm Animals. 1st ed, 2011; pp. 1-14.

- Nelson Cattle Artificial Insemination Techniques, 2010.

- Risco CA. Management and Economics of Natural Service Sires on Dairy Herds In: Chenowech P.J. (Ed.): Topics in Bull Fertility, International Veterinary Service, 2000.

- Rogers P. Bovine Fertility and Control of Herd Infertility. Grange Research Center, Dunsany, Co. Meath, Ireland, 2001.

- Salverson R, Perry G. Understanding Estrus Synchronization of Cattle. South Dakota State University – Cooperative Extension Service –USDA, 2005; pp.1-6.

- Shiferaw Y, Tenhagen BA, Bekana M, Kasa T. Reproductive performance of crossbred dairy cows in different production systems in the central highlands of Ethiopia, 2003.

- Sinishaw W. Study on semen quality and field efficiency of AI bulls kept at the National Artificial Insemination Center. Msc Thesis, Addis Ababa University, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Debre Zeit, 2005.

- Tadesse A, Zeleke M, Berhanu B. The Status and Constraints of AI in Cattle in the three selected districts of Western Gojjam Zones of Amhara region, Ethioipia. Department of Animal Production and Technology, College of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, School of Graduate Studies Bahir Dar University. Journal of Agriculture and Social Sciences ISSN Printing 1813-2235; ISSN: 1814-960X, 2010; pp. 103.

- Artificial Insemination, 2008.

- Webb DW. Artificial Insemination in Cattle. University of Florida, Gainesville. IFAS Extension, DS 58, 2003; pp. 1-4.

- Webb DW. Artificial Insemination in dairy cattle, 2010.

- Zewde E. Artificial Insemination and its Implementation. Ethiopian Society of Animal Production (ESAP). Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2007; pp. 7-14, 29, 45.

- Zewdie E, Deneke N, FikreMariam D, Chaka E, HaileMariam D, Mussa A. Guidelines and Procedures on Bovine Semen Production. NAIC, Addis Ababa, 2005.