Amputation as Morbidity Cause by Traditional Bone Setters in Jos University Teaching Hospital

Mancha DG*, Ode MB, Amupitan I and Onche II

Department of Orthopedics and trauma, Jos University Teaching Hospital, Nigeria

Received Date: 21/06/2021; Published Date: 09/07/2021

*Corresponding author: Mancha DG, Department of orthopedic and trauma, Jos University Teaching Hospital, Jos, Email: drdmgmancha2@yahoo.com, Phone number: +2348027256680

Abstract

Background: Amputation is a formidable source of debility in healthy persons who sustain injuries to extremity. These injuries are often treatable and individuals could walk out of the hospital to face challenges of daily living. In our setting however, they often found themselves moved from one care giver due to the perceived sub-optimal care rendered. These care givers most of the time are traditional bone setters who play tremendous and sometimes horrendous role in most orthopedic related pathologies afflicting the extremities. These add to the burden of orthopedic related pathologies in our daily practices in our communities. The rising number of patronage and the fact that all age groups are affected portends formidable hindrance to efforts of providing optimal care.

Design: A retrospective study

Setting: Jos University teaching Hospital, North central Nigeria

Materials and Method: A retrospective study of patients that had amputations from complications arising from traditional bone setter’s intervention during the ten years January 2004 to December 2013 in Jos University Teaching Hospital. Seventy five out of 302 that had amputation had initial trauma from road traffic accidents sought unorthodox treatment from traditional bone setters. A significant number were found to be avoidable but for the intervention of traditional bone setters. We highlight the relative morbidities arising from these alternatively sought care givers to the rising number of cache of amputees in our community.

Data were obtained from folders and operation records and analyzed using epi info version 3.5.3.

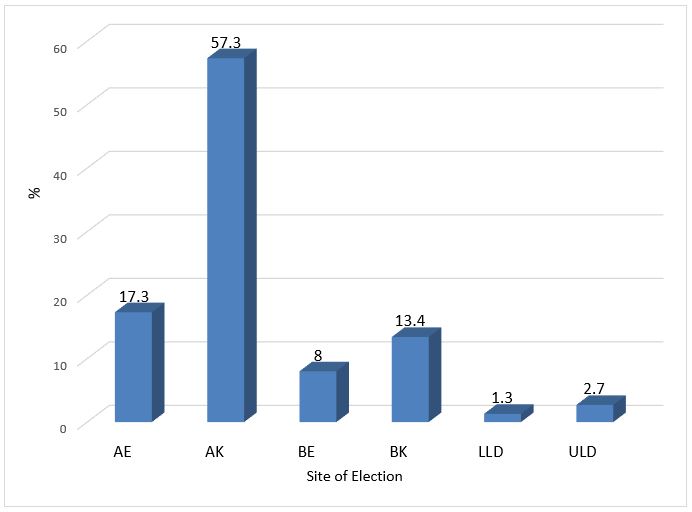

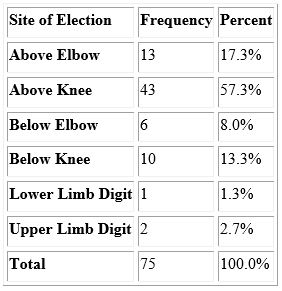

Results: Out of 302 patients that had amputation out 75(24.8 %) were as a result of complications from interventions of the traditional bone setters. There were 50 male and 25 females making a male: female ratio of 2:1. Mean age of 24.9+_ 16.9 years. Those who had it on the left were 39(52%) while 34(45.3%) on the right extremity. All the patients presented with gangrene. Wet gangrene in 29 and gas gangrene in 11 the rest were mixture of these. The victims cut across all social strata and age groups with 71(94.7%) of them victims of trauma who were further traumatized by the unwholesome practices of traditional bone setters. Almost half 34(45.3%) are below eighteen years old and all were offered major limb amputations. Major limb amputations accounted for 43(57.3%) above knee amputation and 10(13.3%) below knee amputation, 13(17.3%) above elbow, 6(8%) below elbow. Only 1(1.3%) accounted for lower limb digit and 2(2.7%) for upper limb digits. Multiple surgical interventions were offered in 39(52%) patients while 1 patient underwent 3 interventions. Above knee amputation was offered on 43 (57.3%) of the patients. Seven died as result of overwhelming sepsis and anemia despite blood transfusion at the time of presentation.

Keywords: traditional bone setters, amputation

Introduction

Traditional bone setting is practiced in all communities in Nigeria and in other parts of the world [1,2,3]. Despite our current civilization it coexists alongside orthodox medical practice [4]. The World Health Organization WHO (2002) reported that alternative medicine accounted for over 80% of health care in Africa [5]. The aspect of TBS is a specialized form of traditional medical (alternative medicine) practice that is inherited from generations with some passive informal apprenticeship mainly among family members. The basis of this practice is hinge on powers conferred by intuition, superstition, spiritual and insight of knowledge of use of natural elements such as herbs leaves, soil and supper natural forces [6,7]. Traditional bone setting is part of the general alternative and unorthodox medical practice that exist in our society and whose presence has been with us for as long as the society existed [1,2,3]. The practice cuts across all specialties such that they coexist with religious practitioners, herbalist, traditional birth attendants and more recently churches and mosques. It is important to note that despite availability of modern-day medical care, traditional bone setting is practiced in developing countries of Africa, Asia and south America [6].

Many reasons have been adduced to encourage patronage of traditional bone setters. Among these are beliefs, low cost, fear of plaster of Paris, quick service, fear of surgery, amputation, non-availability of qualify medical personnel and pear pressure from family and friends [8,9]. The practitioners are often in remote part of the town and decision to convey the patients lies on the persons present at the scene and time of accident. This is also mooted by third parties, relatives’ friends and old patients [4,10]. Besides only little finances are required from victims at presentation. Sometimes these patients and their benefactors decline orthodox intervention with no clear justification. They form the bulk of signings against medical advice in our accident and emergency units and on the wards [10,11]. Where multiple injuries are sustained patients’ relations allow the hospital to tidy up only head injuries and open wounds within few days and subsequently decline further care of the extremities.

Victims of traumatic injuries bear most of the brunt of this early transfer to traditional bone setters. This is because in most instances decisions are taken without the consent of the patients themselves as it is always difficult for a victim to make decisions [9]. Problems usually arise at the time of sorting or triage of various individuals and injuries in which the practitioner does not know the limit of his trade and when he is irrelevant. The extent of intervention and the scope of their practice know no bound as they intervene where the trained hands exercise much caution. This is in spite of lack of formal education among most of them [3]. The result of these is the application of concocted preparations on open wounds, tight splint on sites that ought not to be, inscription scar form marks where it may predispose to infection. While the use of splint may be useful in some cases in most instances may be needless. This is because the practitioners lack basic knowledge of anatomy, physiology and radiology.3Plane radiographs often exposes the limits of intuition in their practice. The outcome of these is the unacceptable grotesque limbs that are not only endangered but pose a threat to the patient’s life.

Although it had existed for centuries and still commands patronage it falls short of ethical, scientific and legal standard of care. The is evident by the increased detailed morbidity such as nonunion, mal union, increased amputation risk among under 16 [12,13]. This clearly shows the process of traditional bone setting almost always heralds a recipe for failure. From the consent formulation, dressing protocol, the materials, the splints, the process of splinting with respect to control of pain and tissue and patient handling are all debatable. Much therefore need to be done to evolve and make the practice more scientifically relevant and acceptable.

Ignorance and faulty believes about management of traumatic fractures, poor diabetic control due to patients’ reliance on claims by itinerant traditional bone setters claim to cure diabetes have been adduced to contribute to preventable limb loss, livelong deformities and sometimes death [14]. These contribute to increase the morbidity associated with extremity injuries. Many centers have reported interference of these old practice in the patient care in our environment. When the outcome of their interventions is not desirable to the bone setters themselves, they refer such to established hospitals.

Over the years there seem to be a rise in the number despite improve accessibility to hospital care. In view of the alarming nature of the morbidity and mortality emanating from traditional bone setter’s intervention we set to review the challenges faced by attending physicians in the care of these patients. Often because the dear need to safe the patient other elective is jettisoned. These challenges are so demanding that the impact affects other patients care despite scrupulous attempt to salvage these limbs the necessary is almost always amputation. What was initially dreaded by the victim ultimately becomes the aftermath of his beliefs and practice in seeking the traditional remedy. diverts routine limb reconstruction to damage control of mutilated limbs that pose thread to life.

We highlight the relative contribution of these alternatively sought care to the rising number of cache of amputees in our community.

Patients and Method

A retrospective study of patients that had amputations from complications arising from traditional bone setter’s intervention during the ten years January 2004 to December 2013 in Jos University Teaching Hospital. Seventy-five of our patients were offered amputation not due to primary pathology but complications of care traditional bone setters. These injuries range from ankle injuries, tibia and fibula fractures and few from diabetes mellitus and extremely few from peripheral vascular disease. These categories of patients were selected from the accident and emergency unit of Jos university teaching hospital. The documented records of were extracted from the admission records, theater records and folders. The pattern of initial injuries, mechanism of injuries, of amputation, number of interventions in the course of treatment and complications were recorded. Permission was sought from the ethical committee of the institution. A significant number were found to be avoidable but for the intervention of traditional bone setters. Data obtained from folders and operation records were analyzed using epi info version 3.5.3.

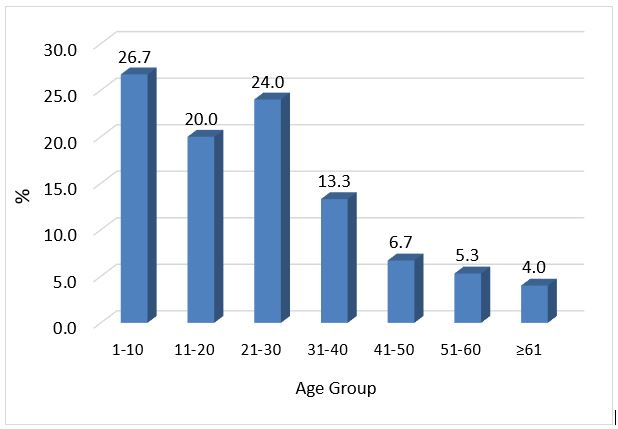

Table 2: Age group disposition of patients that had tbs intervention.

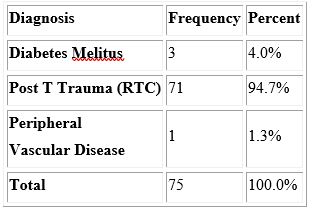

Table 1: Patient,S diagnosis prior to TBS intervention.

Results

Out of 302 patients that had amputation out 75(24.8 %) were as a result of complications from interventions of the traditional bone setters. There were 50 male and 25 females making a male: female ratio of 2:1. Mean age of 24.9+_ 16.9 years. Those who had it on the left were 39(52%) while 34(45.3%) on the right extremity. All the patients presented with fulminating sepsis and gangrene. Wet gangrene in 29 and gas gangrene in 11 the rest were mixture of these. The victims cut across all social strata and age groups with 71(94.7%) of them victims of road traffic crash who were further traumatized by the unwholesome practices of traditional bone setters. Almost half 34(45.3%) are below eighteen years old. Major limb amputations accounted for 72(96%). Above knee amputation 43(57.3ss%) and 10(13.3%) below knee amputation, 13(17.3%) above elbow, 6(8%) below elbow. Only 1(1.3%) accounted for lower limb digit and 2(2.7%) for upper limb digits. Multiple surgical interventions were offered in 39(52%) patients while 1 patient underwent 3 interventions. Above knee amputation was offered on 43 (57.3%) of the patients. Seven died as result of overwhelming sepsis and anemia despite blood transfusion at the time of presentation.

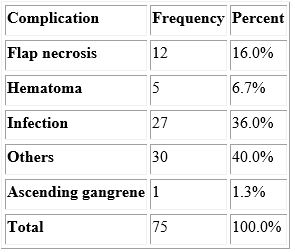

Table 3: Outcome of intervention.

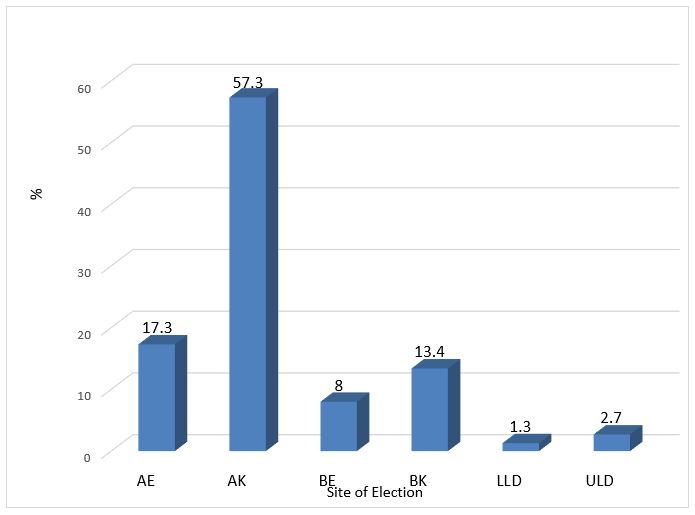

Sites of election after tbs intervention

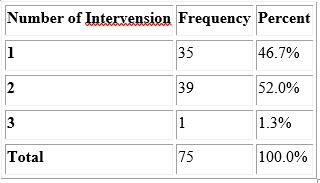

Table 4: Morbidity in terms of interventions.

Sites of Level of Election After TBS Intervention

Levels of Amputation

Discussion

A significant number of patients 75(24.8%) who had amputation were initially treated by Traditional Bone Setters. This is a common practice especially among victims of road traffic crash who had either sustained fracture or dislocation. (Table 1). The patronage of these practitioners enjoys the goodwill that cut across educational and social barriers [16]. This large number may not be unconnected to the believe that traditional bone setters intervention heals faster than orthodox interventions besides the prolong wearing of cast that result in atrophy, gangrene and subsequent surgical intervention by way of amputation and loss of lives in some cases [16]. However more disastrous outcome had been recorded in most of these patients [13,14]. Unfortunately, these horrific outcomes are in most cases outside the public glare and only noticed in hospital setting. It was found that failure rate among those that opted out of traditional treatment was up to 65% [12]. The extent of some of these interventions and their outcome have been described as unacceptable [15].

Trauma from road traffic crash constitute the largest number of causes of injury related casualty and disability (Table 1) and affects more males than female gender. Male: female ratio was 2:1. This is corroborated in finding from other parts of the country because they get involve in injury prone activity [10,18,24]. A large number of these patients patronizes traditional born setters immediately after injury and before arrival to major hospitals 74.4% and 31.8% in Port Harcourt, Kano respectively [17,18]. They do this in order to assuage their sense of urgency and panic that puts them in dear need for help at all cost. The sympathizers of the victim are mainly friends and relatives present at the time of injury and who often think alike [17]. A large number are conveyed to bone setters as result of the myth that accidents and diseases have spiritual components and the despondency and helplessness of road traffic accident victims, their rescuers and the panic that ensues makes this group of patients highly vulnerable to the counsel of traditional bone setters. This is also influence by widespread believe across ethnic, religious and social strata that traditional bone setters perform better than the orthodox medical intervention with underlying myth that accidents and diseases have spiritual components [14,19].

Although other conditions such as conge nital anomalies also consult traditional bone setters, the bulk of what present to hospitals were fractures 71(94.7%) (Table 1). Dislocations are also notice [19,20]. The low access to the Health Insurance Scheme and the high cost of modern orthodox orthopedic care that is said to be prohibitive also contributes to this. One cannot however underscore the prevailing economic crunch in the country where majority live below the WHO defined poverty line. The tendency is for the patients to seek the cheapest care affordable to them or pull out of an established treatment scheme when finances become inaccessible [14,23]. They often decline treatment and constitute a significant number signings against medical advice on admission [25].

It is pertinent to note that in spite of the debility cause by diabetes very few of them patronize the traditional bone setters. Despite lack of awareness of measures of foot care among known diabetic patients which is largely due to a lack of education (19) they do not frequently patronize traditional bone setters. This revealed by our findings as only 3(4%) (Table 1) diabetics were victims of traditional bone setter’s intervention.

Large number of our patients with significant patronage were below thirty years (Table 2). These are dependent age in with decisions are made on their behalf and because most of them don’t earn a living. In fact, they form the bulk of unemployed and most vulnerable group as they cannot fend for themselves. The degree of damage and morbidity is worse among the young too because any attempt to resist the painful splints or protest the effect of tight splints are always rebuffed or scolded by the parent or care giver. The excruciating pains are often to be regarded as part of the treatment. In adults however, they often pull and throw off the tight splint as soon as he/she could not stand the pain and discomfort.

The vulnerability in children was elaborated by Nwadiaro et al in 1999 where it accounted for over 75% amputation in children [13]. In the decade after that we noticed 34 (45.3%). The fact that children are mainly involved portend a growing number of disable youths that could be rendered handicap later in life. This creates burden of rehabilitation and dependency as more of the young and productive age group are affected. The situation may be more pathetic as it also shrinks their employment opportunities [21]. With this alarming number of patients presenting as emergency as consequence of traditional bone setters’ intervention will soon assume a major public health concern. Needless to say, that most of the victims die before presenting to recognized health facility.

We noticed these victims of traditional bone setters were brought in severe morbid life-threatening forms that requires rapid intense intervention. These conditions include wet gangrene, gas gangrene or combination of such, severe anemia, uncontrolled sepsis, tetanus, deranged electrolytes, uncontrolled blood sugar were all features to contend with by the attending physician. Others include compartment syndrome. These critical conditions present in moribund state warranted that amputations were performed as live saving measure. Suffice to mention that recorded mortality were as a result of worsening of this critical condition.

When patients present with life threatening gangrenes of the extremities known factors that determine the site of election and level of amputation no longer hold sway. What becomes important is the nature and amount of healthy skin tissue that can be mobilized directly to be able to construct a healthy stump. The fulminating necrotic tissues now serves as a limiting determinant in the establishment the level of amputation. In our instance the ability to raise a healthy flap rather than the initial pathology becomes the main determinant of the level of amputation. With this, commonest level of amputation is a high above knee amputation because necrosis from various forms of gangrene renders only little healthy skin is available to fashion a healthy stump whether above knee or below the knees. A plausible intervention critical to survival of the patient was a modified guillotine amputation with or without pre-fashion flap. This rids the impending ascend of gangrene and accounted for multiple interventions in 40(53.3%) patients (Table 4). With this extended proximal levels of amputation, more complex and sophisticated prosthesis will be required. But availability of this necessity is completely absent in our setting.

The effect of these is the development of multiple complications in over 45(60%) of the patients. Most of these complications are those that warranted reoperation and so added prolong hospitalization, cost of treatment and morbidity associated with anesthesia and nosocomial infection.

In conclusion traditional bone setters form the point of first consult among victims of traumatic injuries of the extremities from road traffic crash. Healthy skin flaps are more determinants of anatomical site of election than the primary pathology and levels of amputation more likely more cephalad because they often present with gangrene. More of the young are expose to this practice than the adults mainly because choice of care givers are made on their behalf. This, if not mitigated will creates a large cache of young amputees with burden rehabilitation to the society. The need for documentation of these horrific practice of traditional bone setter’s intervention practices is highly desirable.

Our limitation lies on the hospital-based study more emphasis was on restoration of lives as the patients were in life threatening conditions. A prospective study would have been plausible

References

- Ogini LM. Traditional bone setting in Western Nigeria. In Biodun Adediran (Editor) Cultural studies in Ile Ife. Institute of African Studies, Obafemi AwolowoUniversity, Ile-Ife.1995; 202-208.

- Agaja SB. Prevalence of limb amputation and role of TBS in Nigeria. Nig J. surgery 2000; 7(2): 79.

- Chowdhury AM, Khandker H.H., Mostafa A.G. Why patients patronize traditional bone setters?Dinajpur Med.Col J 2013; 6(1): 17-20.

- Ogunlusi JD, Ikem IC, Ogini LM. Why patients patronize traditional bone setters?The internet J of orthoprdic surg.2007; 4(2): 1-7.

- Ejima OS. Traditional bone setting among Igala people of Kogi state, Nigeria. Intern. J Basic and Applied Sci World Health Organization.Traditional medicine strategies 2002 Geneva. 2002-2005.

- Ekere AU. The scope of extremity amputations in a private hospital in south south region of Nigeria Niger J med.Oct.Dec.12(4): 2258s.

- Omololu AB, Ogunlade SO, Gopalsani VR. The practice of traditional bone setting: Training algorithm. Cln. orthop and related res, 2008; 466:2392-2398.

- Sina OJ, Taiwo OC, Aodele IM. Traditional bone setters and fracture care in Nigeria.Merit res. 2014; 2(6): 074-0.

- Nwadiaro HC, Nwadiaro PO, Kitmas AT, Ozoilo KN. Outcome of traditional bone setting in the middle belt of Nigeria Nig. JournaL of clinical Research 2006.

- Solagberu BA. Long bone fractures treated by traditional bone setter: a study of patient behavior, Tropical Doct, 2005; 35(2): 106-10811.

- Popoola SO. Onyemachi NOC, KortorJN, Oluwadiya KS. Leave Against Medical Advice(LAMA) from in-patient orthopedic treatment..SA orthop J Spring 2013; 112(3): 58-61.

- Ogini LM. The use of traditional fracture splint for bone setting. Med. Pract, 1992; 1992: 49-51.

- Nwadiaro HC, Liman HU, Onu MI, Ozoilo KN. Presentation of complications among orthopedic inpatients. Nig J surg. Sci.1999; 9: 34-37.

- Dada AA, Yunusa W, Giwa SO. Review of the practice of traditional bone setting in Nigeria. J African Health sciences, 2011.

- Alonge TO, Dongo AE, Notidde Te, Omololu AB. Ogunlade S.O. Traditional bone setteres in south western Nigera. Friends or foes? West aAfrican J of medicine, 2004; 23(1): 81-85.

- Nwadiaro HC, Ozoilo KN, Nwadiaro PO. Determinants of patronage of traditional bone setters in middle belt of Nigeria.J Assoc. Res. Doc. Niger.17(3): 356-359.

- Ekere AU, Echem RC. Patronage of Traditional bone setters for musculoskeletal conditions. Port Hacourt Medical journal, 2012; 215-224.

- Ajibade A, Akiniyi OT, Okoye CS. Indications and complications of major limb amputation in Kano,Nigeria.Ghana Med. J, 2013; 47(4):185-188.

- Olaolorun DA, Pladiran IO, Adeniran A. Complications of fracture treatment by traditional bone setters in south west Nigeria.Fam. pract, 2001; 18(6): 635-637.

- Thani LOA, Ogini LM. Factors influencing patronage of traditional bone setters.WAJM, 19(3): 220-224.

- Phillipo LC, Joseph BM, Ramesh MD, Isdori HN, Alphonce BC, Nkinda M, Japhet M. G Major Limb Amputations: A Tertiary Hospital Experience in Northwestern Tanzania J of Orth Surg and Research, 2014; 1-9.

- Akande T, Salaudeen A, Babatunde O. Effects of National Health Insurance scheme on utilization of health services in Unilorin Teaching Hospital Ilorin, Nigeria.

- Udosen AM, Otei OO, Onuba O. Role of traditional bone setters in Africa:Experience in Calabar,Ngeria.Ann Afri Med. 2006; 5: 170-173.

- Onyemaechi NOC, Onwuasoigwe O, NwankwoOE, Schuh A. PopoolaSO.Complications of musculoskeletal injuriestreated by traditional bone setters in developing country.Indian j of applied res.2014; 4(3): 313-316.

- Jimoh BM, Anthonia O, Chinwe I, Oluwafemi A, Ganiyu A, Haroun A, et al. Prospective evaluation of discharge against medical advice in Abuja, Nigeria.The scientific world J, 2015; 3(1): 4817.