Synovial Sarcoma of the A1-A2 Vertebra in A 3-Year-Old Child Presented as Tonsillitis: Case Report and Systematic Review

Maria Vousvouki, Vasiliki Antari, Konstantinos Kouskouras, Athanasios Tragiannidis, Maria Palabougiouki, Maria Ioannidou, Nikolaos Foroglou, Theodotis Papageorgiou, Emmanouil Hatzipantelis*

Children and Adolescent Hematology - Oncology Unit, 2nd Pediatric Clinic of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, School of Medicine, AHEPA University General Hospital of Thessaloniki, Greece, bpedclin@auth.gr

Radiology Department of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, School of Medicine AHEPA University General Hospital of Thessaloniki, Greece, radiologyauth@gmail.com

Neurosurgery Clinic of Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, School of Medicine, AHEPA University General Hospital of Thessaloniki, Greece, patsalas@auth.gr

Received Date: 04/04/2021; Published Date: 19/04/2021

*Corresponding author: Associate Professor in Pediatric-Pediatric Hematology, St. Kyriakidi 1, Post code: 54636, Thessaloniki, Greece, Tel: +30 2313303509, Mobile: +30 6974319949. Email: hatzip@auth.gr

Abstract

Synovial sarcoma is a rare, high-grade soft tissue sarcoma, which affects both sexies, pediatric and adult age groups, and is characterized by local invasiveness and distant metastases. We describe a 3-year-old girl, referred to the emergency department with fever, nervousness, and food-fluid refusal, 8 days after tonsillectomy, due to noisy breathing that started 9 months ago. During hospitalization, opisthotonus and walking instability were noticed and an emergent CT scan demonstrated a large mass at the region of atlas-axis joint (A1-A2) with filtration of the nasopharynx. Pathology reported a biphasic synovial sarcoma and the child started chemotherapy, due to unresectable mass. Six months from protocol completion, there was remission with unfortunate outcome.

Keywords: Synovial sarcoma, child, vertebra.

Introduction

Synovial sarcoma is a high grade, soft tissue sarcoma, derived from undifferentiated mesenchymal cells [1]. The name came from its resemblance to synovial tissue and its close proximity to tendon sheaths, bursae and joint cavities [2]. Synovial sarcoma is included in the large and heterogenous group of Non-Rhabdomyosarcoma Soft Tissue Sarcomas (NRSTS), which are relatively insensitive to chemotherapy [3]. Soft tissue sarcomas represent 1% of all cancers worldwide and synovial sarcoma account for 10-15% of all STS [1,4]. It affects both pediatric and adult age groups, most often in the 3rd decade of life [1,2]. Both sexes are affected, with male predominance [2]. In children and adolescents (<20 years of age) the annual incidence rate is 0.5 to 0.7 per million [5].

Case Report

A 3-year-old girl referred to the emergency department with fever, nervousness, and food-fluid refusal. Eight days ago, she underwent tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy and myringotomy, due to noisy breathing and cervical pain, started 9 months ago. The patient was treated with clindamycin and ceftriaxone, due to high suspicion of abscess in the postoperative region. Swollen cervical lymph nodes was the only clinical finding.

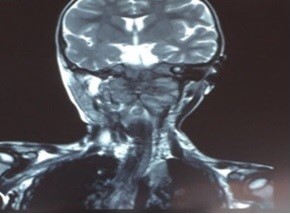

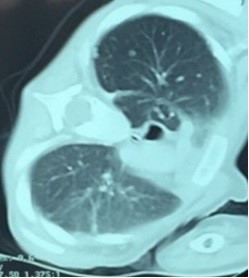

During hospitalization fever did not improved, whereas opisthotonus and walking instability were revealed, 7 days later. An emergent CT scan of skull and cerebrum was performed, that demonstrated a large mass at the region of A1-A2 vertebra with filtration of the nasopharynx, the clivus, the occipital bone and both the jugular foramens, applying pressure on the spinal cord, with lytic areas on them. MRI scan of the area showed similar findings (Figure 1). CT scan of thorax showed several metastatic lesions at both lungs (Figure 2), while PET-CT scan showed no evidence of metastatic areas at the bones.

Diagnosis after surgical biopsy and histopathology analysis was that of biphasic synovial sarcoma, with both spindle and epithelial cells, while from immunopathology positive EMA, AE1/AE3, vimentin, cytoceratine 8/18 and CD34 were found. Tumor was considered to be unresectable at that time and chemotherapy started, according to the EpSSG NRTSS 2005 protocol (stage IRS IV). After 5 cycles completed, significant reduction of the mass and no evidence of pulmonary metastases observed, while the tumor remained unresectable. Because of the age of the patient, the location of the tumor and unfavorable prognosis, as well as, parents concern, radiotherapy was not decided.

Six months from chemotherapy protocol completion, there was remission, with enlargement of the mass, filtration of the A1-A7 vertebras and the spinal cord, pathologic enrichment at MRI scan and metastatic areas at the lungs. The child started chemotherapy again with ICE protocol. After 2 cycles, no improvement of the mass observed and the patient passed away due to respiratory complications.

Figure 1: MRI scan of scull and cerebrum: large mass at the region of A1-A2 vertebra with filtration the nasopharynx, the clivus, the occipital bone and both the jugular foramens.

Figure 2: CT scan of thorax: multiple metastatic areas at the lungs.

Discussion

Synovial sarcoma is an uncommon, high-grade soft tissue sarcoma, derived from primitive mesenchymal cells, which explain the diverse location [5,6]. It is characterized by local invasiveness and metastases, specially to the lungs (16-25%) and rarely to regional lymph nodes (<1%) [5,7]. It is characterized by a specific chromosomal translocation [t(x;18) (p11.2; q11.2)], in which the SS18 gene on chromosome 18 (previously called SYT) fuses with one of the several synovial sarcoma X (SSX) genes on chromosome X, which results in the formation of a chimeric gene that encodes a transcription-activating protein. 9SSX genes had already been described, but the most common are SS18-SSX1 (66%) and SS18-SSX2 (33%) [5,6,8,9]. This translocation is present in 90-95% of cases. Although, it’s not clear yet how these mutations affect the prognosis, it seems that patients with SS18-SSX2 have a more favorable outcome, than those with SS18-SSX1 [5,9].

Synovial sarcoma usually presents as a soft, palpable, slowly growing, painless tissue mass, with will defined margins, often misdiagnosed as a benign situation, due to vague symptoms [1-6,8]. More often, it arises in soft tissues of the extremities, in the 66% of the cases, especially adjacent to large joints (not intra-articular) but it can also be present in rare and unexpected sites, such as retroperitoneum, mediastinum, bones, nerves, blood vessels, visceral organs, head and neck regions [5,6]. In early stages, it is possible that it can be present as pain and tenderness, without evidence of mass, which can be misdiagnosed as inflammatory arthritis, tendinitis etc [2].

Our patient was initially misdiagnosed as having a respiratory tract infection, with possible formation of abscess to the postoperative area, after tonsillectomy, adenoidectomy and myringotomy. Only after opisthotonus and walking instability were revealed, tumor in the cervical vertebrae area and the spinal cord was included in differential diagnosis, while myeloblastoma is considered the most usual CNS tumor at this age.

Imaging findings of synovial sarcoma are not pathognomonic and usually reveal a well-defined, round or lobulated, soft tissue mass. Calcifications are found approximately in 30% of the patients, which may be focal or disseminated, with fine, stippled or opaque appearance [5,10]. Necrotic and hemorrhagic areas are frequently detected [6]. As for all soft tissue masses, MRI is the choice examination, because of its tissue contrast and the ability for multiple planes, allowing evaluation of the extent of the tumor. In our case, MRI showed an heterogenous mass, with peripheral and potty enrichment of the contrast media.

Definite diagnosis can only be set with biopsy and histological analysis. Three histological subtypes can be distinguished: a) monophasic (55%), b) biphasic, c) poorly differentiated1. Monophasic contains only spindle cells, whereas biphasic both epithelial-like and spindle cells. Poorly differentiated is more aggressive and tends to metastase more often [2,5,6]. The most sensitive immuno-histochemical staining for synovial sarcoma are positive EMA, cytokeratin, AE1\AE3 and E-cadherin, in combination with negative CD34 [6]. Additionally, recently it has been reported that synovial sarcoma has decreased immunoreaction of the nuclear tumor suppressor gene SMRRCB1\INI1, which is proposed as a sensitive and specific marker to discriminate synovial sarcoma from other neoplasms [8,11]. Synovial sarcoma is staged using TNM classification.

Metastases occur more often to the lungs and they are present in 16-25% of cases, usually in the first 2-5 years of treatment. More rarely, they can appear to lymph nodes and bones [1,2,12]. In our case, metastases on the lungs were present at the initial diagnosis, which after the chemotherapy were eradicated, but after remission increased both in number and size.

Many synovial sarcoma classification systems have been used but the North American Intergroup Rhabdomyosarcoma study group grading system is established [5]. IRS group I is defined as completely resected primary tumor, IRS group II is defined as microscopically involved margins after initial surgery, IRS group III is defined as gross residual disease after primary surgery or biopsy, and IRS group IV is defined as metastatic disease at diagnosis. Risk factors are: IRS group, site of primary tumor and metastases. Synovial sarcoma should be differentially diagnosed from desmoid tumor, mesenchymal chondrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, cyst etc, according to its location [6].

First line treatment is of course the surgical excision [5,13]. The feasibility of surgical resection, with clear margins, is of great importance [5,13]. If a complete resection cannot be done, biopsy is recommended, chemotherapy and a delayed surgical removal [1]. Until recently, pediatric oncologists considered synovial sarcoma as a chemosensitive tumor and a course of at least nine adjuvant chemotherapy was considered as appropriate, with response rates between 60-65% [5,14]. More recently, Italian and German pediatric retrospective study of initially grossly resected synovial sarcoma, suggested that patients with tumor size <5cm, that was completely resected, do not need chemotherapy or radiotherapy, thus have a very low risk of metastasis [3]. Analysis in pediatric patients treated on three prospective European studies, demonstrated that for those patients with complete surgical resection and response to chemotherapy, can avoid radiotherapy [3]. The most important treatment factor is the efficiency of the surgical resection. Radiotherapy can be omitted in low-risk patients, so as to avoid radiotherapy-related long-term toxicities [3,5]. The patient described was first treated with chemotherapy, due to IRS IV stage, but remained tumor was still considered unresectable. Radiotherapy was not decided, due to its location, at the region of A1-A2 vertebra, the clivus, the occipital bone and both the jugular foramens, the difficulty in radiation and the possible life-threatening post-radiation complications, in addition with parents concerns and denial. At the time of remission clinical condition did not allow radiotherapy.

Patients with local recurrence have a significantly better survival rate than patients with distant metastases [3]. The average time for relapse is 4 to 103 months (median:20 months). Five-year and 10-year survival rates after relapse are very low (29.7% and 21% respectively). Patients should be followed up for at least ten years [5,15]. In conclusion, synovial sarcoma is an aggressive tumor of the mesenchymal cells, which should be first treated with feasible surgical resection, while there is controversy about the utility of radio- and chemotherapy.

Authors Contributions

Emmanouil Hatzipantelis conceived, designed, supervised and did editing of the manuscript

Maria Vousvouki collected data and wrote the manuscript

All authors collected data, reviewed and approved draft of the manuscript

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest

Grant Information

The authors received no specific funding for this work.

Acknowledments

Not applicable

References

- Scheer M, Dantonello T, Hallmen E, Blank B, Sparber-Sauer M, Vokuhl C, et al. Synovial Sarcoma Recurrence in Children and Young Adults. Ann Surg Oncol 2016; 23: 618-626.

- Gary M, Daniel L, Onya V, Evan A. Synovial Sarcoma in the Foot of a 5-Year-Old Child. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2016;106: 283-288.

- Ferrari A, Chi Y, De Salvo G, Orbach D, Brennan B, Randall R, et al. Surgery alone is sufficient therapy for children and adolescents with low-risk synovial sarcoma: A joint analysis from the European paediatric soft tissue sarcoma Study Group and the Children’s Oncology Group. Eur J Cancer 2017; 78: 1-6.

- Ferrari A, De Salvo GL, Brennan B, Noesel M, A De Paoli, Casanova M, et al. Synovial sarcoma in children and adolescents: the European Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Study Group prospective trial (EpSSG NRSTS 2005). Ann Oncol. 2015; 26: 567–72.

- Kerouanton A, Jimenez I, Cellier C, Laurence V, Helfre S, Pannier S, et al. Synovial Sarcoma in Children and Adolescents. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2014; 36: 257-262.

- Kritsaneepaiboon S, Sangkhathat S, Mitarnun W. Primary synovial sarcoma of the abdominal wall: a case report and literature review. Radiol. Case Rep 2015; 9: 47-52

- Ferrari A, De Salvo GL, Oberlin O, Casanova M, A De Paoli, Rey A et al. Synovial sarcoma in children and adolescents: a critical reappraisal of staging investigations in relation to the rate of metastatic involvement at diagnosis. Eur J Cancer 2012; 48: 1370-1375.

- Bianchi G, Sambri A, Righi A, Dei Tos AP, Picci P, Donati D. Histology and grading are important prognostic factors in synovial sarcoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2017 Sep; 43:1733-1739.

- Kubo T, Shimose S, Fujimori J, Furuta T, Ochi M. Prognostic value of SS18-SSX fusion type in synovial sarcoma; systematic review and meta-analysis. Springerplus 2015; 4: 375.

- Hirsch RJ, Yousem DM, Loevner LA, Montonw KT, Chalian AA, Hayden RE, et al. Synovial sarcomas of the head and neck: MR findings. Am J Roentgenol. 1997; 169: 1185–1188.

- Kohashi K, Oda Y, Yamamoto H, Tamiya S, Matono H, Iwamoto Y, et al. Reduced expression of SMARCB1/INI1 protein in synovial sarcoma. Mod Pathol Off J US Can Acad Pathol Inc 2010; 23: 981–990

- Ferrari A, De Salvo GL, Oberlin O, Casanova M, A De Paoli, Rey A, et al. Synovial sarcoma in children and adolescents: a critical reappraisal of staging investigations in relation to the rate of metastatic involvement at diagnosis. Eur J Cancer 2012; 48:1370-1375.

- Brecht IB, Ferrari A, Int-Veen C, Schuck A, Mattke AC, Casanova M, et al. Grossly-resected synovial sarcoma treated by the German and Italian Pediatric Soft Tissue Sarcoma Cooperative Groups: discussion on the role of adjuvant therapies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2006; 46: 11–17.

- Ferrari A, De Salvo GL, Dall’Igna P, Meazza C, De Leonardis F, Manzitti C, et al. Salvage rates and prognostic factors after relapse in children and adolescents with initially localised synovial sarcoma. Eur J Cancer 2012; 48: 3448-3455.

- Speth BM, Krieg AH, Kaelin A, Exner GU, Guillou L, Hochstetter AV, et al. Synovial sarcoma in patients under 20 years of age: a multicenter study with a minimum follow-up of 10 years. J Child Orthop. 2011; 5: 335–342.