Gunshot Wound to the Mastoid with Facial Nerve Repair

Labby Alex B, Lee Kevin K and Yu Jeffrey W*

Department of Otolaryngology, The University of Illinois, USA

Received Date: 28/02/2021; Published Date: 16/03/2021

*Corresponding author: Yu Jeffrey W, Department of Otolaryngology, The University of Illinois at Chicago, USA.Address:1855 W, Taylor Street, Chicago, Illinois 606012. Email: jeffwyu@uic.edu

Abstract

Penetrating facial trauma resulting in facial nerve damage requires a complex operation for repair and perseveration of function. We report a case of self-reported gunshot wound resulting in facial nerve transection and high vagal nerve injury. The patient underwent vocal fold injection medialization followed by mastoid wound exploration and repair of the facial nerve using a greater auricular nerve cable nerve graft. This case combined procedures from the breadth of the otolaryngological surgical field. With increased concern for skill fragmentation and specialization in the field of otolaryngology, this case highlights the value of skilled generalist otolaryngologists.

Keywords: Facial nerve; Facial nerve trauma; Gunshot wound; Facial nerve repair

Introduction

Penetrating facial trauma resulting in facial nerve damage requires a complex operation for repair and preservation of function. We report a case of self-inflicted Gunshot Wound (GSW) in a 35-year-old female that resulted in injury to the right mastoid and cranial nerves VII, IX, and X, who underwent surgical exploration and repair of the ipsilateral facial nerve using skills available to a well-trained generalist Otolaryngologist. With transection of the facial nerve by GSW, a graft is typically required, such as the greater auricular or sural nerve [1,2]. The majority of patients will require mastoidectomy with the repair for to offer best facial nerve outcomes [1].

Case Report

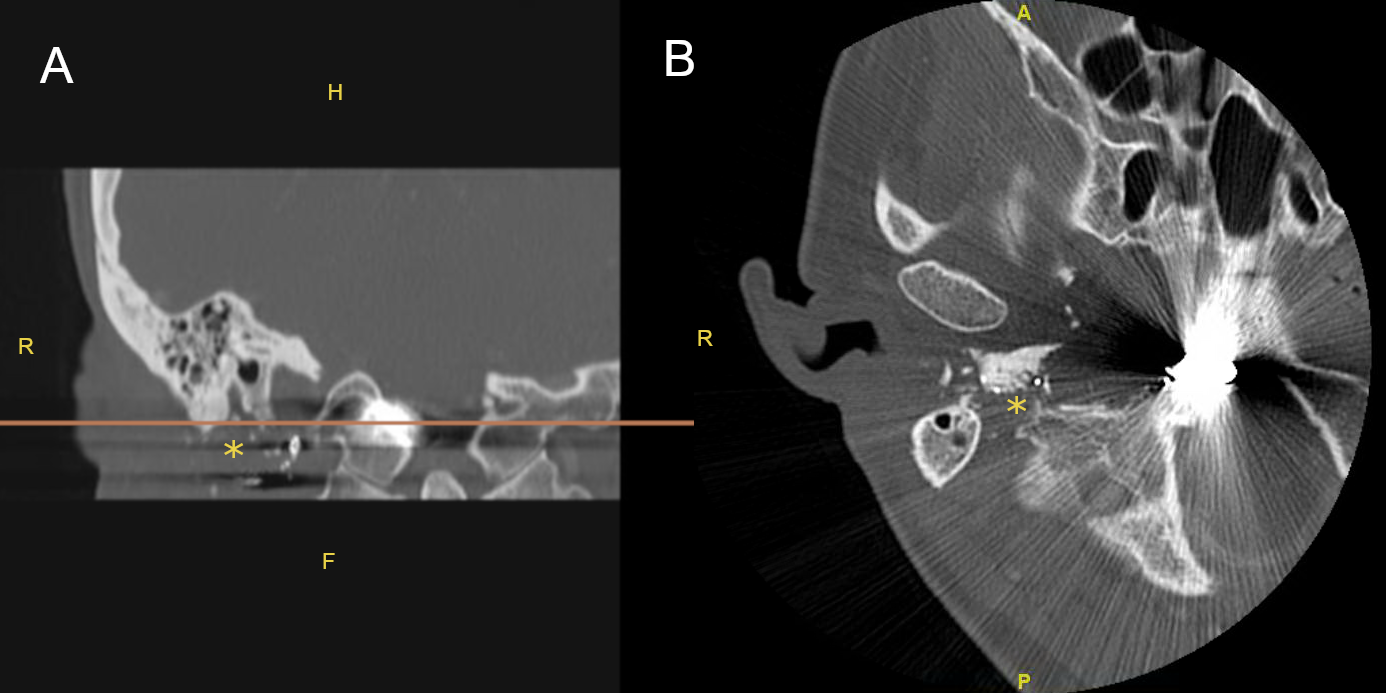

Following a full trauma evaluation, our service was consulted for a 35-year-old female following a self-inflicted GSW to the right temporal bone with resultant right-sided hearing loss and facial palsy (Figure 1).

Exam noted right facial nerve paresis, asymmetric soft palate elevation with left uvular deviation, and breathy voice. The right pinna was intact with crusted blood obstructing the ear canal. Laryngoscopy revealed a right paretic true vocal fold. Imaging of the right temporal bone demonstrated a severely comminated mastoid tip and stylomastoid foramen. Bullet fragments tracked from the mastoid tip to lateral to the clivus.

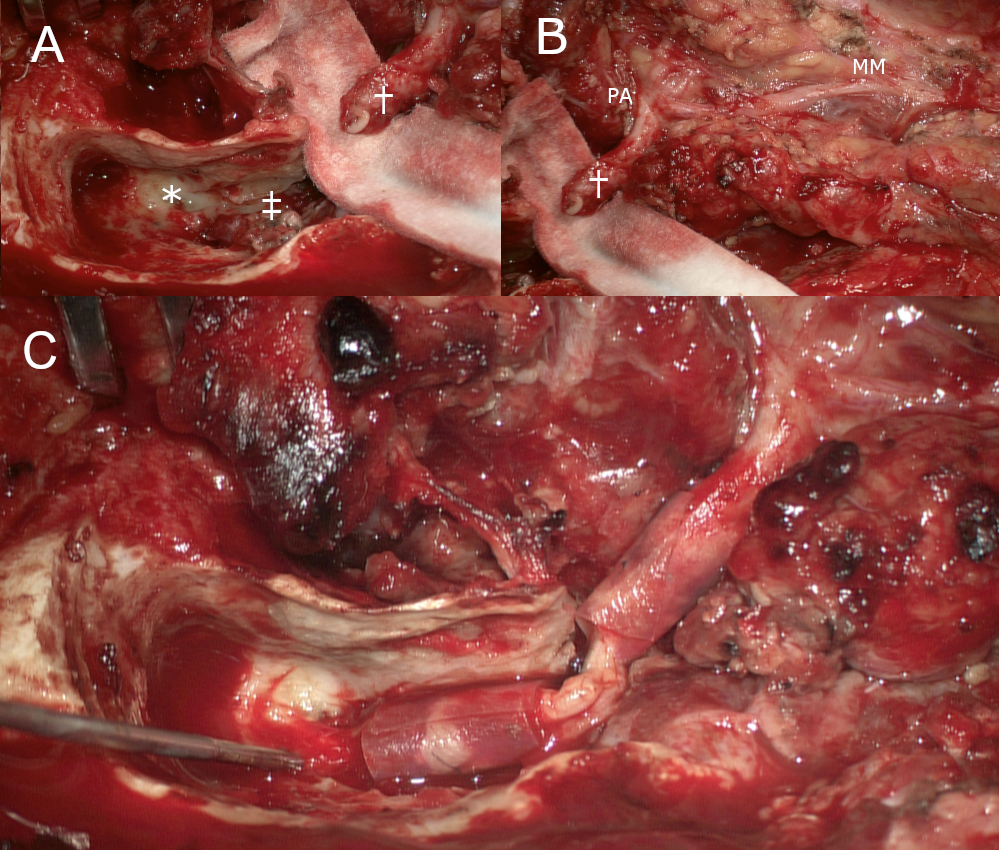

Following stabilization, the patient first underwent right injection vocal fold medicalization. A post-auricular incision was made combining a mastoidectomy with a modified Blair incision. The mastoid was exposed and the facial nerve was initially approached in superficial parotidectomy fashion with elevation of sub-SMAS flap and identifying tragal pointer and digastric muscle belly. Singed tissue and a bullet cavity were present, and the facial nerve had been transacted at the mastoid tip. No structures showed response using a facial nerve stimulator. The distal branch of the marginal mandibular nerve was identified near the mandibular notch and a retrograde approach was used to identify the main trunk of the facial nerve by tracing the marginal branch backward.

To identify proximal nerve, we performed a cortical mastoidectomy. The vertical facial nerve was identified and the remaining mastoid tip was removed to access the stylomastoid foramen. The proximal facial nerve was decompressed through the stylomastoid foramen. The facial nerve was mobilized out of the facial nerve canal in the vertical segment of the facial nerve and the proximal nerve stump was identified. Approximately 8 cm of the greater auricular nerve was harvested and divided into two cable grafts. The grafts were then sutured without tension to the ends of the facial nerve with 8-0 nylon epineural stitches. Axo Guard Nerve Protector (AxoGen, Inc, Alachua, FL) was placed around the graft sites (Figure 2), then the incision was closed. Exemption from the Institutional Review Board of the University of Illinois - Chicago was obtained.

Figure 1 – CT image of right temporal bone

A: Coronal image of right temporal bone, line indicates level of axial image shown in B;

B: Axial image of right temporal bone with bullet fragment

Figure 2 – Intra-operative right facial nerve repair

A: Right mastoid; B: Distal facial nerve; C: Repaired facial nerve. : lateral semi-circular canal; ‡: proximal facial nerve; †: distal facial nerve; MM: marginal mandibular nerve; PA: pes anserinus

Discussion

This case describes the repair of traumatic transection of the main trunk of the facial nerve at the site of the stylomastoid foramen with a nerve graft. This case consisted of vocal fold injection medialization, neck exploration and parotidectomy approach for identification of the distal facial nerve, cortical mastoidectomy with identification of the proximal facial nerve, and nerve harvest for cable graft. Graduating residents require the exposure to a minimum number of Key Indicator cases, including some procedures utilized by this case.

The concern for skill fragmentation with increased sub-specialization has been a persistent discussion topic. In 1994 as fellowship pursuit was becoming more commonplace, Bailey identified driving motivations that were broadly divided into enhanced patient care versus career success.1 A 2007 editorial by Dr. Sataloff noted 39% of graduating residents pursued additional training, with that number increasing in a in 2011 to 58% [3,4]. A more recent review found that for data from 2008-2014, more than half of residents planned for the pursuit of fellowship training. There was with an increasing trend over time as well as being significantly associated with interest in working in an academic setting [5,6].

Despite the mechanism of fellowship pursuit, the perception that there is a 5. Shrinking role for generalist otolaryngologists remains. There remains a dearth of data specific to fellowship pursuit in our specialty, including ascribed motivating factors, resident perceptions, and longitudinal follow-up after fellowship completion. The fact remains that individuals who maintain the breadth of procedural skills taught during training are uniquely qualified to manage the described case by integrating surgical expertise from our diverse field. No other type of surgical specialist can manage facial nerve trauma at the level of the stylomastoid foramen and the phonatory sequelae of vagal nerve injury. With the addition of appropriate psycho-social treatment, the comprehensive understanding of voice, swallowing, and facial nerve weakness positions the generalist otolaryngologist as the optimal clinician to provide clinical follow-up and related care-coordination necessary for the described patient’s success.

References

- Bento R, de Brito R. Gunshot Wounds to the Facial Nerve. Otology & Neurotology 2004, 25: 1009-1013.

- Gordin E, Lee T, Ducic Y, Arnaoutakis D. Facial Nerve Trauma: Evaluation and Consideration in Management. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2015; 8(1): 1-13.

- Sataloff R. Fellowship training in otolaryngology. ENT-Ear, Nose and Throat Journal. 2009; 88(9): 1084-1086.

- Golub J, Ossof R, Johns III M. Fellowship and Career Path Preferences in Residents of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. Laryngoscope. 2010; 121: 882-887.

- Bailey BJ. Fellowship proliferation: impact and long-range implications. Archives of Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery. 1994; 120: 1065-1070.

- Wilson M, Vila P, Cohen D, Carter J, Lawlor C, Davis K, Raol N. The Pursuit of Otolaryngology Subspecialty Fellowships. Otolaryngology - Head and Neck Surgery. 2016; 154(6): 1027-1033.