An Uncommon Case of Streptococcus Pyogenes Endocarditis Causing Intracranial Mycotic Aneurysms

Ameur A1, Belharty N1, Rhemimet Ch1, Laktib N1, Lahfidi A1, Boumaaz M2, Loudiy N1, Mouine N1, Asfalou I3, Lakhal Z4 and Benyass A3

1Clinical cardiology service, Military hospital, Rabat

2Radiology service, Military hospital, Rabat

3Non-invasive cardiac exploration service, Rabat

4Cardiology intensive care service, Military hospital, Rabat

Received Date: 10/10/2020; Published Date: 13/11/2020

*Corresponding author:Ameur Asmaa, Clinical cardiology service, Military hospital, Rabat. Email: asmaaameur.18@gmail.com

Abstract

Intra-Cranial Mycotic Aneurysms [ICMA] or infection aneurysms are rare and represent less than 10% of the neurological complication of infective endocarditis. The most common causative organisms are alpha-hemolytic streptococcus of the viridans group and staphyl ococcusaureus, respectively responsible for 50%and10%ofICMA.

We report a case of group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus –streptococcus pyogenes- native mitral valve endocarditis complicated with intracranial mycotic aneurysms. A review of the existing literature revealed that acute IE caused by streptococcus pyogenes has rarely been reported, only 40 cases since 1940, of which no case was complicated with intracranial mycotic aneurysm.

Keywords: Infective endocarditis; Streptococcus pyogenes; Intracranial mycotic aneurys

Introduction

Infective endocarditis is an uncommon infectious disease with an annual incidence that varies from 3 to 7 per 100 000 person-years. Although relatively rare, IE continues to be characterized by increased morbidity and mortality through its complications [1].Neurologic complications related to IE are diverse (ischemic, hemorragic and infective), and are the most frequent extracardiac complications, occurring in 17 to 82% of patients with left-sided IE [2].

Mycotic aneurysm are rare inflammatory neurovascular lesions, comprising 0.7 – 5.4% of all intracranial aneurysms. S.viridans and S.aureus are the most common organisms that cause IE. Therefore, they are the two most frequently associated pathogens with CMAs in the course of IE[3]. Streptococcus pyogenes, whilst known to infect immunocompromised patients, is a rare cause of endocarditis and there are no published reports of this organism causing intracerebral mycotic aneurysms. We report a case of streptococcus pyogenes endocarditis complicated within tracranial haemorrhage in the setting of cerebral mycoticaneurysm.

Case Presentation

An 18-year-old female was admitted with a one-month history of persistent fever, associated with shortness of breath and precordialgia. She had previously received some unspecified treatment with no apparent amelioration of symptomatology. She reported a history of dental procedure, undergone one year earlier. Physical examination, showed a temperature 38.5°C, (Blood pressure: 120/70, Heart rate= 100 beats/minute, respiratory rate=20 breaths per minute). Cardiovascular examination revealed an intensive mitral holosystolic heart murmur. Osler nodes were observed on fingers andtoes.Biological test revealed anaemia of chronic inflammation, blood cell count= 10500/μL, platelet count= 360000/μL, prothrombin time-international normalized ratio=1.23, C- reactive protein=98mg/dL, creatinine=6mg/L and estimated glomerular filtration rateof138.5 mL/mn. The urine analysis was negative for infection. Electrocardiograson demonstrated sinus tachycardia, and Chest x-ray demonstrated cardiomegaly with features of left atrialenlargement.

Blood cultures were found to be positive for streptococcus group A (Streptococcus pyogenes).

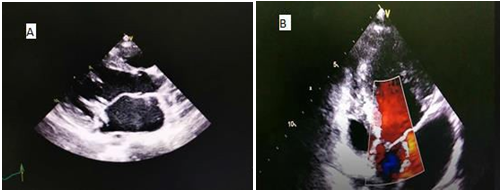

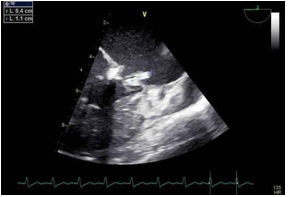

A transthoracic echocardiogram, along with a Trans oesophageal echocardiography, documented a severe mitral regurgitation and a 16×6mm vegetation, attached to the anterior mitral leaflet and 8 mm vegetation implanted on the tricuspid valve was also noted (Figure 1and 2) Pan-computed tomography (CT) scans revealed features of splenic infarction, with no other sign of secondary lesions elsewhere.

Figure 1A: Transthoracic two-dimensional echocardiography (parasternal long axis view): Arrow showing vegetation on the anterior mitral leaflet. B: Transthoracic two- dimensional echocardiography (apical Four chamber view with color flow mapping displaying a mitral valve regurgitation.

Figure 2: The transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) documented a mobile filamentous structure attached to the mitral valve suggestive of vegetation.

She met two major and three minor modified Duke Criteria and was diagnosed with definite endocarditis. The neurological examination was steadily normal, and ECG was undergone daily, during antibiotic therapy.

A Trans oesophageal echocardiography was repeated 9thday of antibiotic therapy, it showed three calcified masses implanted on the two leaflets of the mitral valve, with the following dimensions (14mm, 13mm, 6mm), and suspected a perforation of the anterior mitral leaflet. A decision of cardiac surgery wastaken.

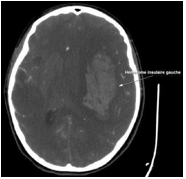

16thdayofantibiotictherapy,she reports headache and drowsiness, a CranialCT-scanshoed an intracerebral haemorrhage located in the left frontal and insular lobes with manifest signs of cerebral herniation (Figure3).

Figure 3: Cranial computed tomography (CT) revealed a subcortical ICH in the left frontal and insular lobes right.

The patient was admited in intensive care unit, where a decompressive craniectomy was conducted.

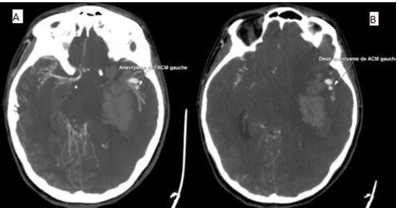

Thereafter, a cerebral CT angiography was done, giving evidence of two aneurysms arising from the ending of the left middle cerebral artery (Figure 4).Given the poor prognosis, endovascular therapy was precluded. She died after a rapidly progressive decline in her condition.

Figure 4 (A,B): Cerebral CT angiography was done, giving evidence of two aneurysms arising from the ending of the left middle cerebral artery.

Discussion

Beta haemolytic streptococci, which include serogroups A, B, C and G, cause a wide variety of infections including cellulitis, necrotising fasciitis, bacteremia and infective endocarditis [4]. Although BHS endocarditis is relatively uncommon, it is very aggressive, with a high rate of cardiac valve destruction, cardiac abscess formation and systemic embolization [4].Of the different subgroups, group B streptococcus (S.agalactiae) is the most common cause of BHS endocarditis. BHS Endocarditis due to groups C and G are less common, but presents similarly to that caused by group B BHS [4].It is noted that Group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes is the least common cause of BHS endocarditis [4].Forty cases of endocarditis caused by Streptococcus pyogenes in children and adults have been reported since 1940, with a median age of 32 years, ages ranging from four months to 80 years. The mortality rate was 24% (62.5% before 1990 and 15.4% after 1990) and was mainly due to cardiac failure and/or septic shock; most patients recovered after antibiotic therapy [50].In our case, the outcome was dramatic, due to a neurologic complication, namely, intracranial haemorrhage. Intracranial Mycotic aneurysm, which results from the septic embolism of vegetation in the cerebral circulation, has been reported secondary to infective endocarditis, with an estimated range between 2% and 10%, The most common causative organisms being Streptococcus viridans, Streptococcus group D and Staphyl ococcusaureus species [6].The clinical presentation of unruptured ICMAs is variable and lacks specificity: Fever, headache, convulsions and focal deficit. Ruptured ICMAs are responsible of a clinical profile of cerebral or subarachnoid haemorrhage: headache, loss of consciousness, intracranial hypertension and focal deficit[7].The diagnosis of ICMAs is possible on brain CT scan that visualises the indirect signs. Cerebral angiography, cerebral MRI and/or cerebral angio MRI have a 95% sensitivity in diagnosing ICMAs greater than 5mm. CT angiography may not be sufficient to detect small aneurysms at the base of the skull[7].Brain angiography remains the benchmark examination, in particular for the diagnosis of small ICMA[7].In our case, cerebral CT angiography gave evidence of two aneurysms.Mortality associated with rupture of intracranial mycotic aneurysm, leading to subarachnoid haemorrhage or intracerebral haemorrhage, is reported to be as high as 80%[6].There are, however, no published reports of S.Pyogenes causing intracerebral mycotic aneurysms.Treatment of intracranial mycotic aneurysms is challenging and to date, there are no standard guidelines. Antibiotic therapy is an essential component of the treatment and studies have reported variable rates of resolution in response to antimicrobial therapy [6]. Taking into consideration the variable response to antibiotics and the high rate of mortality associated with rupture of intracranial mycotic aneurysms, some authors have advocated more aggressive treatment, using endovascular or open surgical treatment, to permit securing of aneurysms and timely cardiac valve replacement [6]. Furthermore, timing of cardiac surgery is difficult to determine, owing to the cerebral damage thatmaybeamplifiedbyheparinizationandhypotensionduringthe cardiopulmonary bypass or postoperative anticoagulant therapy. Therecent European society of cardiology guidelines recommend, that after ICH, surgery should be postponed for more than one month [3].In our case, the clinical presentation has deteriorated rapidly, even after the decompressive craniectomy.

Conclusion

Group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus pyogenes IE is a rare condition, however, it can be lethal through extra cardiac complications, which is approved through our case which confirms its virulent character. There are currently no guidelines in treatment of Intracranial mycotic aneurysms in the setting of IE, rendering its management extremely challenging.

References:

- Larry M Baddour, Walter R Wilson, Arnold S Bayer, Vance G Fowler and Imad M Tleyjeh. Infective Endocarditis in Adults: Diagnosis, Antimicrobial Therapy, and Management of Complications. A Scientific Statement for Healthcare Professionals From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;132(15):1435-86.

- Salaun E, Touil A, Hubert, S, Casalta J-P, Gouriet F, Robinet-BorgomanoE et al. Intracranial haemorrhage in infective endocarditis. Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases. 2018.

- Yuan S-M and Wang G-F. Cerebral mycotic aneurysm as a consequence ofinfective endocarditis: A literature review. Cor et Vasa, 2017;59(3):e257-65.

- Abdelghani El Rafei, Daniel C DeSimone, Christopher V DeSimone, Brian D Lahr, JamesM Steckelberg, Muhammad R Sohail, et al. Beta- haemolytic streptococcal endocarditis: clinical presentation, management and outcomes, InfectiousDiseases. 2016.

- Sarda C, Magrini G, Pelenghi S. Mitral Valve Infective Endocarditisdue to Streptococcus pyogenes: A Case Report. Cureus.2019;11(4):e4461.

- Afshari F T, Al-Lawati K, Chavda S, Billing S and Flint G. Cerebral mycotic aneurysms secondary to Streptococcus Agalactiae induced infectiveendocarditis.British Journal of Neurosurgery.2017;1-3.

- R Sonnevillea, I Kleinb, L Bouadmaa, B Mourvillier, B Regnier, M Wolff. Complications neurologiques des endocardites infectieuses. Réanimation. 2009;18:547-55.