Case report: Chlamydia Infection Mimicking Ulcerative Colitis

Dario Palhares*

University of Brasilia, Brazil

Received Date: 21/09/2020; Published Date: 23/10/2020

*Corresponding author: Dario Palhares, University of Brasilia, Brazil, and Email: dariompm@unb.br

Abstract

It is presented a case initially thought to be ulcerative colitis, as the patient had diarrhea, blood and mucus in the stools and had an ulcer in the rectum. Histopathological exam pointed to a chronic, inespecific inflammation. After a wide serological screening, with IgM positive to Chlamydia and a high titer of IgG, the patient was treated with antibiotics and is clinically cured.

Keywords: Azitrhomycin, Tetracyclin; Doxycyclin; Colonoscopy; Inflammatory bowel disease

Introduction

Ulcerative colitis is one of the presentations of inflammatory bowel disease, related to a disorder in the immune system [1,2]. The main clinical symptoms are: diarrhea, tenesmus, evacuation urgency, presence of blood and mucus in the stools. This clinical condition is chronic and can cause several complications, intestinal, nutritional and lesions in other organs [1,2]. On histopathological exam, ulcerative colitis is shown as a diffuse inflammation restricted to mucous and submucous layers occurring only at colon and rectum [1,2]. There can be since erosions on the mucosa layer to commitment to the muscular layer. It is common the presence of polyps and pseudopolyps[1,2].

The diagnosis is complex and is carried out by set of clinical manifestations and its temporal evolution, laboratory evaluations and biopsies; there is no hallmark capable to confirm or deny the diagnosis [1,2]. Same way, the differential diagnosis is very complex, since the most frequent symptoms of ulcerative colitis are the same as many other diseases3. It is presented a clinical report in which the initial, more probable diagnostic hypothesis was of ulcerative colitis, but at the end it showed to be rectal infection of Chlamydia. The treatment of ulcerative colitis is based on aminosalycilates, corticoids, immunossupressants and, more recently of immunobiologicals, but some patients only find relief with the surgical removal of colon and rectum [1,3], while Chlamydia is an infectious disease curable by the correct use of antibiotics [4,5].

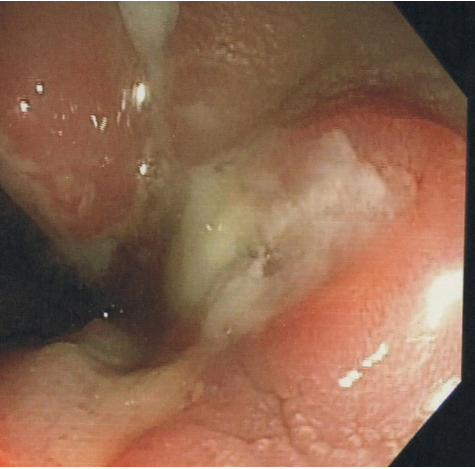

Case: male patient, 50 years old, 1.80m, 77kg, normotensive, previously healthy. He referred a daily intestinal rythm of one or two dejections per day, but suddenly he could not evacuate for about 7 days, when finally he started to present a daily intestinal rythm of three to five dejections, most of them with blood and mucus. Every day he noticed blood in the stools, but not on all dejections. The physical exam was normal, and anuscopy did not show hemorrhoids, fissures or ulcers. He underwent biochemical blood exams, normal. Negative to HIV and VDRL. Parasitological stool examination revealed Blastocystis hominis, treated with nitazoxanide. Further exams did not show protozoans nor worms, but the symptoms remained. Upper digestive endoscopy was normal, negative to Helicobacter pylori. Colonoscopy showed a sessile polyp of 5mm diameter in sigmoid colon. Histopathological exam showed mucosa layer with intense inflammatory activity and polyp with no abnormal cells. He started using mesalazine suppositories, with reduction of mucus on the stools, but persistence of blood. Hemogram was normal, with 6,100 leukocytes/mL (53% segmented, 7% eosinophils, 1% basophils, 34% limphocytes, 5% monocytes). Protein C of 4.88 mg/dL (limit for inflmmation: 5.00 mg/dL). Negative to antinuclear factor, anti-DNA and tissue antitransglutaminase. Negative to the tumoral markers: CEA, CA 125, CA19/9, alpha-fetoprotein. Fecal pH of 6.0, negative to fecal leukocytes and fat. Fecal calprotectin of 289 mcg/g (reference: smaller than 50 mcg/g). After six months using mesalazine, he underwent a new colonoscopy that revealed one ulcer in the border between anus and rectum and a diffuse proctitis (Figure 1). The biopsy showed regular organization of the tissues, with mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate in the lamina própria and no lymphocytic infiltrate in the epithelium. Immuno-histochemistry negative to cytomegalovirus, herpesvirus and Epstein-Barr´s virus. The patient was then referred to a more detailed screening for infectious diseases. At ten months of clinical evolution, the exams showed: negative to HIV, VDRL, anti-treponemic antibodies, hepatitis C, antigonococcal antibodies. Immune pattern to hepatitis A and susceptible to hepatitis B, referred to vaccination against hepatitis.

B. PPD non reactive (0 mm). Urinary search of chlamydia and gonococcus was negative. Serology was strongly reactive against Chlamydia trachomatis: IgG of more than 250 U/mL (reference: 15.0 U/mL) and IgM of 19.3 U/mL (reference 14.0 U/mL). As a coincidence, while he waited for the result of the blood exams, he underwent a dental treatment in which he took azithromycin for five days, with complete remission of the symptoms. As he got the results, an additional treatment with 7 days of doxycycline was carried out. After one year of follow-up, no more symptoms were reported.

Figure 1: Presence of an ulcer in the transition between rectum and anus, as observed and biopsied after 6 months from the beginning of the clinical symptoms. It was later revealed to be caused by Chlamydia trachomatis infection.

Discussion

At the beginning of the clinical investigation, the principal diagnostic hypothesis was of ulcerative colitis. The clinical symptoms, the presence of a polyp were compatible to this hypothesis, and the markers of intestinal inflammation were positive, notably the fecal calprotectin. However, the histopathological exam at the sixth month of evolution did not show elements commonly seen in ulcerative colitis, such as neutrophilic infiltrate in mucous and submucous layers; mucosal edema, focal hemorrhage, depletion of mucus [1,3]. Instead, the exam showed a chronic inflammatory process pointing out to a secondary cause of proctitis. Immuno-histochemistry screened for three common virus, but at the end the final diagnosis was serological. In this way, the presence of IgM after so much time of clinical evolution was the principal marker of active infection. If this patient showed only IgG, perhaps the diagnosis would have not been so clear.

Compared to 1833, when the first clinical description of the veneral lymphogranuloma was done [6], the taxonomical classification of the bacteria of the family Chlamydiaceae has changed a lot, especially in the last ten to fifteen years, with protein and molecular markers [7-9]. Currently, it is considered that this family comprises a single genus – Chlamydia – with 16 obligatory intracellular parasite species. Two species, C. trachomatis and C. pneumoniae, infect humans, causing conjunctivitis (and subsequent blindness), pneumonia (and subsequent death) and anogenital inflammation (and subsequent infertility). Chlamydia trachomatis is subdivided into three biovars, according to the disease provoked (conjunctivitis, veneral lymphogranuloma or inespecific anogenital inflammation) [7-9]. The biovars are subdivided into serovars according the occurrence of certain major outer membrane protein complexes, totalling 13 genotypes. The serovars L1 to L3 cause veneral lymphogranuloma; the sorovars A to C cause conjunctivitis and the serovars D to K cause anogenital inflammation, which is frequently asymptomatic or with mild symptoms [7-9].

Being an intracellular parasite, the diagnosis via culture is complex, as not all laboratories of clinical analysis are equipped to do so [1,6]. However, with the appearance of diagnostic resources based on antigenic and molecular markers, several epidemiological screenings have been carried out, showing a prevalence of 5 to 20% according to the population sampled [10-14]. That is, among the sexually transmitted infections, Chlamydia trachomatis shows sharp geographical differences, but occurs with a considerable frequency hence it should be screened more routinely in the daily clinical practice.

Regarding manifestations of anogenital infection by Chlamydia trachomatis, there is a dissociation between genital and anorectal manifestations, that is, there are women who present with only cervicitis/endometritis/salpingitis, with only proctitis or both, as well as there are men who only present urethritis/prostatitis; only proctitis or both[13,14]. In the epidemiological screenings where the sexual practices were lifted up, the practice of anal sex could not be related with the infectious focus, that is, a significant portion of the patients deny this but shows with proctitis as well a significant portion report this but present with only genital infection [13,14].

The treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis infection is done with macrolides or tetracyclines, and quinolones have shown some efficacy [4,5]. The beta-lactams reduce infectivity and speed of replication of C. trachomatis, but they are not very effective in its eradication, and when the patient stops taking them, there can be a growth of a strain resistant to macrolides5. There is the description that a single dose of 1g of azithromycin can eradicate Chlamydia infections, but the therapeutic failure rate, of about 20%, points out that this strategy can induce antimicrobial resistance in a relatively short time [4,5]. To mild anorectal infections, Hocking et al.[5] recommend at least 7 days of antibiotics, while to more extensive forms of veneral lymphogranuloma, the use of antibiotics needs to be extended to 3 weeks or more.

As a conclusion, the case herein reported points out that in the differential diagnosis of inflammatory bowel disease, the search for Chlamydia infections should be reinforced, as it has been commonly done to HIV and syphilis.

References:

- Maranhão D, Vieira A, Campos Características e diagnóstico diferencial das doenças inflamatórias intestinais. Jornal Brasileiro de Medicina 2015;103(1):9-15.

- Tontini G, Vecchi M, Pastorelli L, Neurath M, Neumann H. Differential diagnosis in inflamatory bowel disease colitis. World Journal of Gastroenterology 2015;21(1):21-46.

- Ministério da Saúde. Conitec. Protocolo clínico e diretrizes terapêuticas da retocolite ulcerativa. Brasília: Ministério da Saúde - Conitec, 2020. 64p.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis. Geneva: WHO, 2016.

- Hocking J, Kong F, Timms P, Huston W, Tabrizi Treatment of rectal chlamydia may be more complicated than we originally thought. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 2015;70:961-964. doi:10.1093/jac/dku493

- Neves R, Santos O. Linfogranuloma venéreo – 160 anos de progressos clínicos e laboratoriais. Jornal Brasileiro de Doenças Sexualmente Transmissíveis 1996;8(2):34-40.

- Elwell C, Mirrahshidi K, Engel J. Chlamydia cell biology and pathogenesis. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2016;14(6):385-400. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrmicro.2016.30

- Pannekoek Y, Qi-Long Q, Zhang Y, Ende A. Genus delineation of Chlamydiales by analisis of the percentage of conserved proteins justifies the reunifying of the genera Chlamydia and Chlamydophila into one single genus Chlamydia. Pathogens and Disease 2016; 74: ftw071

- Phillips S, Quigley B, Timms Seventy years of Chlamydia vaccine research. Frontiers in Microbiology 2019;10:70. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00070

- Castro CR, Passos M, Pinheiro V, Barreto N, Rubenstein I, Santos C. Detection of Chlamydia trachomatis in military men with clinical complaints of urethritis. Jornal Brasileiro de Doenças Sexualmente Transmissíveis 2000; 12(Supl):4-11.

- Frias M, Pereira C, Pinheiro V, Pinheiro M, Rocha C. Frequency of Chlamydia trachomatis, Urealplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis in endocervix of women during menacme. Jornal Brasileiro de Doenças Sexualmente Transmissíveis 2001;13(2):5-22.

- Marques CA, Menezes M, Coelho I, Marques CR, Celestino L, Melo M, et al. Genital infection by Chlamydia trachomatis in couples attending in conjugal sterility ambulatory. Jornal Brasileiro de Doenças Sexualmente Transmissíveis 2007;19(1):5-10.

- Jin F, Prestage G, Mao L, Kippax S, Pell C, Donovan B, et al. Incidence and risk factors for urethral and anal gonorrhoea and chlamydia in a cohort of HIV-negative homosexual men. Sexually Transmitted Infections 2007; 83: 113-119. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.021915

- Llata E, Braxton J, Asbel L, Chow J, Jenkins L, Murphy R, et al. Rectal Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections among women reporting anal Obstetrics and Gynecology 2018;132(3):692-697. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002804.