Cardiogenic Shock Following Explanation of a Biventricular Pacemaker

Line Lisbeth O*

Department of Cardiology, Zealand University Hospital (Roskilde), Roskilde, Denmark

Received Date: 10/09/2020; Published Date: 24/09/2020

*Corresponding author: Line Lisbeth Olesen, MD, Department of Cardiology, Zealand University Hospital (Roskilde), Sygehusvej 10, Roskilde 4000, Denmark. Tel: +45-40830421; E-mail: llole@regionsjaelland.dk; olesen.line@gmail.com

Abstract

Due to this unfortunate case about irreversible cardiogenic shock after explantation of a CRT, in a patient with unexplained severe infection and with high-risk ischemic cardiomyopathy, it is recommended to disable the LV-function and observe the patient and the EF before deciding to explant a CRT.

Keywords: CRT Explantation; Cardiogenic Shock; LV-Pacing Disabling; Device Infection; Case Report

Abbreviations: ACS= Acute Coronary Syndrome; CRT= Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy; LV= Left Ventricle; EF= Ejection Fraction; COPD= Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; LM= Left Main Artery; LAD= Left Anterior Descendent Artery; CX= Circumflexus Artery; PCI= Percutaneous Coronary Intervention; CAGB= Coronary Artery Bypass Grafting

Introduction

Cardiogenic shock in patients with chronic systolic heart failure may result from progressive decline in the ejection fraction or acute deterioration precipitated by cardiac or non-cardiac causes such as acute coronary syndrome (ACS), arrhythmias, sepsis [1-3]. This is the first case to be presented where cardiogenic shock developed within a few hours following removal of a cardiac resynchronization therapy device (CRT). Device infection as well as left ventricular (LV) pacing lead extraction are expected to increase [4-12]. In order to avoid an unfortunate outcome as in the present case it is essential to attempt to identify predictors of difficulties and complications. Prior to proceeding with withdrawal of biventricular pacing and lead extraction the consequences should be evaluated [6,7,10].

Case Report

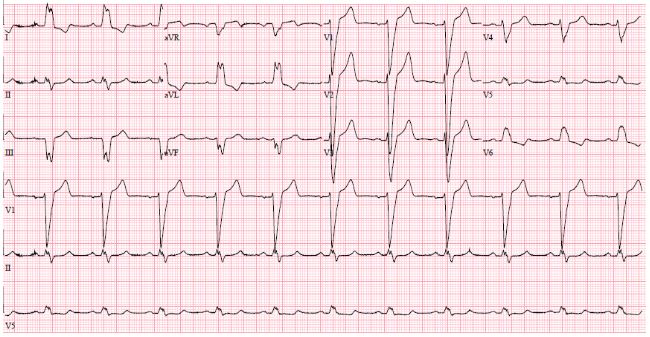

This 70-year-old male had been a heavy smoker since his youth and suffered from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). About 30 years previously, he was diagnosed with arterial hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. He had problems with the peripheral circulation, and 10 years earlier necrosis had started to affect his toes and feet. He was treated with percutaneous transluminal angioplasty of the stenotic femoral arteries, in addition to amputation of the right forefoot and the left crus. In his last year, ischemic and infected wounds again developed on his right foot. He also had psoriatic affection of the skin. One year previously, while on vacation abroad, he suffered a myocardial infarction. Coronary angiography (CAG) showed stenosis of the left main artery (LM), the left anterior descendent artery (LAD), and the proximal circumflexus artery (CX), and he was treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and stents. EF 25% and reduced right ventricular function. Sinus rhythm and left bundle branch block 174 ms. (Figure 1).

The patient received treatment with an angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, beta-blocker, diuretics, statin, and salicylate and was scheduled implantation with a CRT-D. Before this could be realized, however, he was admitted with ACS with EF dropping to 10% and protracted cardiogenic shock with multiorgan dysfunction. Restenosis was revealed in the stented areas and treated with balloon angioplasty. He slowly recuperated.

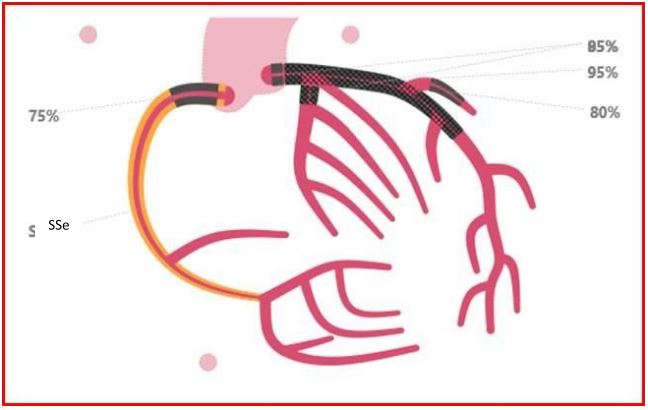

About two months later, he suffered another ACS and in addition to severe in-stent restenosis, corresponding to severe stenosis in the distal LM, the ostial LAD, and the proximal CX, a stenosis in the proximal right coronary artery (RCA) was also detected (Figure 2). He was in a poor state and performing PCI or coronary artery bypass grafting (CAGB) posed a very high risk; instead medical treatment was recommended. His condition remained unstable and characterized by angina pectoris, dyspnea and problems with comorbidities. Due to the poor prognosis, a limited level of treatment was decided in consultation with the patient and his family. This decision was re-evaluated on an ongoing basis.

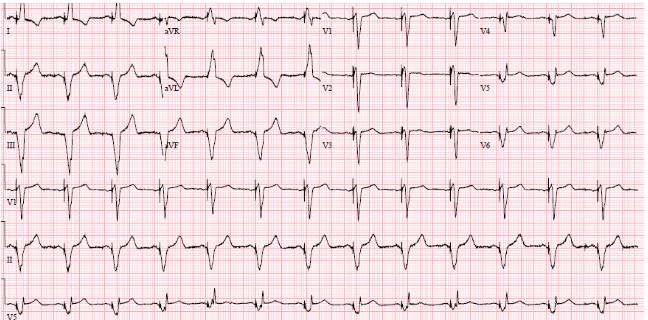

Implantation of a CRT-D was postponed due to septicemia with Staphylococcus aureus, which was cultivated from the blood and from the wound on his right foot. He was administered antibiotic therapy. Three weeks later, all signs of infection had disappeared. However, the leg wound was not completely closed, but the biochemical screenings values were normal. The CRT-D was implanted without complications (an antibacterial envelope was not used). The patient improved, his shortness of breath subsided from NYHA III to NYHA II, and the QRS-duration diminished to 146 ms. (Figure 3).

As the next step, CABG was planned, but had to be postponed due to recidivating septicemia and infection without a recognized focus. Staphylococcus aureus, Staphylococcus epidermidis, and Corynebacterium were cultivated from the blood. Transesophageal echocardiography revealed discrete changes related to a pace lead, no typical vegetations and no valvular involvement. Positron emission tomography-computerized tomography (PET-CT) showed a change in the same area. Specialists were called upon to evaluate the patient, and it was finally concluded that the infection was probably related to the pacemaker, and system extraction was mandated. Percutaneous explantation was performed, 6 weeks after the implantation, by an experienced operator, with simple traction of the leads, and without procedural complications; a few hours later, however, he began to develop shock with falling bloodpressure, and his temperature rose to 38.5. Monitoring echocardiography showed a drop in ejection fraction (EF) from 20% to 5% despite intensive care.He exhibited no pericardial effusion. His condition deteriorated rapidly, and implantation of a new “rescue” CRT was not considered a possibility. In addition, revascularization could have been a solution, but with a very high risk and it was rejected due to his poor condition and the comorbidities. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) and impella were not an option due to the peripheral vascular disease.He did not respond to vasopressor therapy (norepinephrine) and died within 17 hours of surgery.

Figure 1: ECG before CRT. SR with LBBB 174 ms.

Figure 2: CAG. Stenosis LM 85 %, LAD 95 %, D1 80 %, CX 85 %, RCA 75 %.

Figure 3: ECG after implantation of CRT. QRS 146 ms.

Discussion

From a short-term and a long-term perspective, increased mortality is seen in patients who have had their CRT explanted without a new one being implanted [7]. Besides, various surgical complications in connection with the explantation may be fatal [8,12]. However, until now, the occurrence of cardiogenic shock a few hours after explantation has not been described in the literature, which is actually surprising since the condition ought to be expected due to the loss of hemodynamic support and the resultant increased dyssynchrony, hypokinesia, and mitral insufficiency [7,13,14]. In this case, the removal of the CRT precipitated acute malignant cardiogenic shock. There are several likely explanations, because due to end stage cardiomyopathy any perturbation (a procedure, co-illness, infection, blood loss, etc.) could have send him down the road to shock. Shock due to sepsis syndrome was unlikely because no bacteria were cultivated, neither from the leads, nor from the generator pocket. Besides, the patient was administered broad-spectrum antibiotics. Cardiogenic shock is associated with high mortality due to the serious underlying cardiac disease and several risk factors that may trigger an additional impairment of cardiac contractility. Reversible causes of cardiogenic shock should be treated immediately in order to increase the patient’s chances of survival. ACS is the most frequent cause of cardiogenic shock and early revascularization is the most important treatment strategy in cardiogenic shock because it is potentially lifesaving [1-3], as when this patient suffered a cardiogenic shock the first time. Unfortunately, the coronary stenosis recurred and CAG revealed high risk, central, and severe three-vessel coronary artery disease including LM-stenosis, placing the patient at high risk for recurrent shock because even a minor change in blood pressure and hemodynamics could lead to a death spiral.

When neither the precipitating factor, nor the underlying disease is treatable, the prognosis is very poor, and the treatment for cardiogenic shock may only protract the foreseeable course of events and inevitable death [1]. This patient had a number of risk factors predisposing to device infection: Diabetes mellitus, COPD, heart failure, skin disorder, and pre-procedural fever. Device-type is an independent risk factor with CRT being most exposed to infection [4-6]. Device infection carries an ominous prognosis and despite risk of fatal complications due to device removal, the recommended treatment consist of early, complete system extraction, prolonged intravenous antibiotic therapy, and biventricular device reimplantation [4,6-8,10]. In this case, however, minor surgery and closed irrigation with antibiotics [15] or protracted antibiotic treatment possibly had been preferable to explantation because, as became evident, the patient depended with his life upon pacing of the left ventricle [6,10]. Had this been discovered in due course, and before removing the CRT, the LV-pacing could had been disabled and stopped and the patient’s reactions observed before a decision to operate or not was taken. Unfortunately, this was not the case.

Conclusion

A high-risk patient with severe ischemic cardiomyopathy had an infected CRT explanted. A few hours later, he developed irreversible cardiogenic shock. It is suggested to disable LV-pacing and monitor clinical response and EF before deciding whether to remove a CRT.

Funding: The author received no specific funding for this work.

Conflicts of Interest: I have no conflicts to disclose.

References:

- Chioncel O, Parissis J, Mebazaa A et al. Epidemiology, Pathophysiology and Contemporary Management of Cardiogenic Shock – A position statement from the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). doi:10.1002/ejhf.1922.

- Guarracino F, Zima E, Pollesello P, Masip J. Short-term treatments for acute cardiac care: inotropes and inodilators. Eur Heart J 2020;22:3-11. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/suaa090.

- Thiele H, Ohman EM, de Waha-Thiele S, Zeymer U, Desch S. Management of cardiogenic shock complicating myocardial infarction: an update 2019. Eur Heart J 2019;40:2671-83. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehz363.

- Blomstroem-Lundquist C, Traykov V, Erba PA et al. European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) international consensus document on how to prevent, diagnose, and treat cardiac implantable electronic device infections – endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (EPHRS), the Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), International Society for Cardiovascular Infectious Diseases (ISCVID) and the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS). Europace 2020;22:515-6. doi:10.1093/europace/euz24.

- Olsen T, Jørgensen OD, Nielsen JC, Thøgersen AM, Philbert BT, Johansen JB. Incidence of device-related infection in 97 750 patients: clinical data from complete Danish device-cohort (1982-2018). Eur Heart J 2019;40:1862-9. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/eh.

- Sandoe JA, Barlow G, Chambers JB et al. Guidelines for the diagnosis, prevention and management of implantable cardiac electronic device infection. Report of a joint Working Party project on behalf of the British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (BSAC, host organization), British Heart Rhythm Society (BHRS), British Cardiovascular Society for Echocardiography (BSE). J AntimicrobChemother 2015;70:325-59. doi:10.1093/jac/dku383.

- Rickard J, Tarakji K, Cheng A et al. Survival of Patients With Biventricular Devices After Device Infection, Extraction, and reimplantation. J Am CollCardiol HF 2013;1:508-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jchf.2013.05.009

- Sheldon S, Friedman PA, Hayes DL et al. Outcomes and predictors of difficulty with coronary sinus lead removal. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2012;35:93-100. DOI 10.1007/s10840-012-9685-2.

- Greenspon AJ, Patel JD, Lau E et al. 16-Year Trends in the Infection Burden for Pacemakers and Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillators in the United States. J Am CollCardiol 2011;58:1001-6. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2011.04.033.

- Le KY, Sohail MR, Friedman PA et al. Impact of timing of device removal on mortality in patients with cardiovascular implantable electronic device infections. Heart Rhytm 2011;8:1678-85. doi:10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.05.015.

- De Martino G, Orazi S, Bisignani G et al. Safety and Feasibility of Coronary Sinus Left Ventricular Leads Extraction: A Preliminary Report. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2005;13:35-8.

- Ellery SM, Paul VE. Complications of biventricular pacing. Eur Heart J 2004;6:117-21. doi:10.1016/j.ehjsup.2004.05.021.

- Lim K, Choi JO, Yang JH et al. Cardiac Resynchronization Therapy Device Implantation in a Patient with Cardiogenic Shock under Percutaneous Mechanical Circulatory Support. Korean Circ J 2017;47:132-5. https://doi.org/10.4070/kcj.2016.0176.

- Kanhai SM, Viergever EP, Bax JJ. Cardiogenic shock shortly after initial success of cardiac resynchronization therapy. Eur J Heart Fail 2004;6:477-81. doi:10.1016/j.ejheart.2004.02.001z316.

- Lopez JA. Conservative management of infected pacemaker and implantable defibrillator sites with a closed antimicrobial irrigation system. Europace 2013;15:541-5. Doi:10.1093/europace/eus317.