Pseudo-Abdominal Hernia: A Retrospective Study With Review of the Literature

Sunder G*

Department of General and Minimal Invasive Surgery, BPS Government Medical College for Women, Khanpur kalan, Sonepat, Haryana, India

Received Date: 30/06/2020; Published Date: 07/09/2020

*Corresponding author: Sunder Goyal, Department of General and Minimal Invasive Surgery, BPS Government Medical College for Women, Khanpur kalan, Sonepat, Haryana, India. Email: goyal.sunder@yahoo.in

Abstract

Pseudo-abdominal hernia presents as a localizedcompressible abdominal bulge without an actual weakness of muscles. Pseudo hernias have been reported after ventral nerve root damage secondary to excision of radiculopathy, Lyme disease, poliomyelitis, saryngomylia, diabetic truncal neuropathy, polyradiculoneuropathy,prolapsed L1-L2 intervertebral disc and rarely due to Herpes Zoster (HZ). Due to multiple causes of pseudo-abdominal hernias, exact clinical diagnosis isa dilemma for physicians.Sometime, herpetic neuralgia in a dermatomal distribution precedes the rash up to 100 days, thereby, further createsdiagnostic perplexity.Segmental motor weakness (pseudo-abdominal hernia) due to HZ is a rare complication that occurs in 0-5 percent of patients and isassociated with an excellent prognosis for recovery. We carried out a retrospective study at our institution between 2012 to 2016. A total 200 cases of HZ were recorded. Only one case of a 60-year-old man witha typical rash of herpes zoster affecting T11–T12 left dermatomes with pseudohernia was recorded. The abdominal bulgedisappeared completely after 6 months of observation.

Keywords: Pseudo Abdominal Hernia; Herpes Zoster; Herpetic Neuralgia; Segmental Paresis

Introduction

Herpes zoster (HZ), or shingles, is a distinct clinical syndrome, which is the result of the reactivation of a neurotropic virus called varicella-zoster virus. The initial infection causes the acute illness known as varicella, or chickenpox, which typically occurs in childhood. After the primary infection is resolved, the virus remains dormant in the nerve cell bodies of the dorsal root ganglia, cranial nerves, or autonomic system ganglia. The virus can remain inactive for years to decades without causing any symptoms, but can become reactivated and cause a clinical syndrome characterized by unilateral rash and vesicular eruption in the cutaneous distribution of the affected dermatomes. Although HZ affects primarily the sensory nervous system with characteristic painful sensory changes in a dermatomal distribution, segmental zoster paresis has been increasingly recognized as a part of the HZ syndrome [1-8]. Herpes zoster is caused by reactivation of a latent varicella-zoster virus and almost 10-20% of the general population is affected [9]. This virus has afondness for theposterior root ganglia as it is a neurotropic virus and mostly results insensoryneurological complications. There are higher incidence of reactivation among elderly and immunocompromised patients.

About 0-5% of cases develop motor complications inthe corresponding segments to the involvedsensory dermatomes [10]. This may result intoabdominal wall weakness and hence can presentwith abdominal wall pseudohernia andrarely along withcolonic pseudo-obstruction [11].The pseudohernia is due to increased abdominal pressure. The first casereport of motor paresis following herpes zosterwas published in 1886 by Broadbent [12]. The world literature up to 2013 and reported 36 total cases in 35 articles [9]. 37th case has been reported by Bashir Uzma et.al in 2014.We alsoadd to literaturea similar case of dermatomal herpes zoster with subsequent abdominal muscle weakness and formation of a pseudohernia along with colonic pseudo-obstruction.

Material and Method

A retrospective study was carried out in our institution between 2012 to 2016. A total 200 cases of HZ were recorded. 80% patients were in the age group of 40 to 50 years age and male and female ratio was almost equal.10% patients were in between 10 to 20 years and rest 10% were above 50 years of age. 10 to 15% were suffering with ophthalmic HZ and 30% were affected over the chest area. Abdomen was affected in about 40% cases. Upper and lower extremities were affected in the rest of 15% cases. Only one case of a 60-year-old man with typical rash of herpes zoster affecting T11–T12 left dermatomes with pseudohernia was recorded. A search of the MEDLINE, PubMed and Cochrane databases was conducted to identify reports. Manual cross-referencing was performed, and relevant references from selected papers were reviewed.

Case Report

A 60-year-old male presented with an abdominal wall protrusion in the surgery outdoor department for operation. He was a known case of Diabetes Mellitus. Eighteen days earlier, the patient had noticed a painful skin rash that had not been preceded by prodromic symptoms. There was a rapid eruption of skin vesicles and pustules in the area of the left T11-T12 dermatomes, and a clinical diagnosis of herpes zoster was made (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Healing Herpes Zoster Vesicles over left flank.

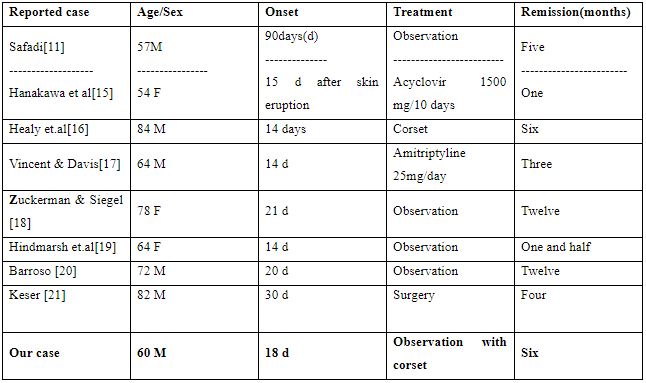

No antiviral therapy was prescribed, and the shingles started fading thensuddenly a bulge appeared in the patient’s left flank. The bulge was painless, compressible, without any sensorial deficit. It got prominent with Valsalvamaneuver. CECT abdomen revealed pseudohernia left flank (Figure 2).

Figure 2: CECT showing Pseudo hernia left flank.

The patient also complained of constipation. There were no other complaints like urinary retention. The neurological examination showed the patient to be essentially normal except for the circumscribed abdominal paresis. Electroneuromyography was performed and the nerve conduction was found to be essentially normal. On needle examination,there was denervation of the external oblique .The bulge remained stable for about two months, and there was slow and gradual remission. It completely resolved within approximately six months. The patient recovered from constipation also.

Discussion

Herpes zoster is caused by a neurotropic virus family of DNA viruses. It affects one or several adjacent dorsal roots. Clinically it presents as vesicular rash in the sensory dermatomes. Rarely,it can damage to anterior horn cells at the same level, resulting in motor muscular weakness. Motor complications can be somatic, including cranial like Ramsay--Hunt syndrome and peripheral like segmental paresis of thelimbs, diaphragm or abdominal musculature and visceral, involving the gastrointestinal, urinary bladder and colonic pseudo dysfunction [2].

The true incidence of segmental zoster abdominal paresis among patients with HZ is unknown sofar and has been cited in different studies as being between 0% to 6% [1,9]. A studiesdone over the general population, pointed out the incidence of herpes zoster to be 1.2-4.8 cases/1000 people per year in all ages and 7.2 to 11.8 cases/1000 per year in those aged >60 years. Thus incidence of HZ increases with age and in immunocompromised individuals.The incidence of segmental zoster paresis which involves focal motor weakness in the same segment as the cutaneous eruption is about 1-5% [13].

Thomas and Howard studied 1210 patients with HZ and found segmental motor involvement in 61 patients (5%) and just 2 patients (0.2%) with abdominal wall paresis [1]. In a study by Chang et al that identified 93 patients with HZ, 11 patients (11.8%) had neurologic complications, and none of them (0%) had abdominal wall paresis [2]. Another study, by Haanpää et al found that, among 40 patients with HZ, 7 (17.5%) had zoster paresis and only 2 (5%) had abdominal paresis[3]. Cioni et al studied 52 patients with thoracic HZ and had only 2 patients with clinical abdominal paresis (3.8%) [4].Chernev et.al.[9] reviewed the world literature and reported 36 total cases in 35 articles. The age range of patients who developed abdominal paresis was 45 to 84 years, with a mean age of 67.5 years and amedian age of 64.5 years. There were 28 male patients and 8 female patients. In 16 patients, the left side was involved, whereas in 18 patients had right-sided symptoms, and, in 2 patients, the side was unspecified.In 32 cases, the herpetic rash preceded the developmentof pseudohernia, in 1 case; the abdominal paresis precededthe rash, whereas, in 3 cases, there was no rash present before or after development of abdominal paresis (zoster sine herpete). The range of onset of pseudohernia after the appearance of the characteristic rash was between 1 and 8weeks, with a mean time of 3.5 weeks. Of the patients who developed the characteristic skin rash, dermatomaldistribution was reported in 30 cases and in 3 cases was not reported. Across the patients with reported dermatomaldistribution of characteristic skin rash, there were 7 different dermatomes affected Dermatomal distribution. Electrodiagnostic studies were performed in 20 cases and were not used in 16 cases. Of the case patients who underwent electrodiagnostic studies, 19 patients had electrophysiologicalchanges that supported the diagnosis ofparalysis and/or paresis of the abdominal musculature. In 2cases, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed, and neither case demonstrated significant changes.Of the 36 cases, 23 patients had complete recovery from their abdominal paresis symptoms. Three patients showedpartial recovery at their follow-ups at 4, 6, and 7 months, respectively. In 3 cases, there was no recovery noted atfollow-up at 5 weeks, 1.5 years, and 3 years. Seven patients were not followed-up to document whether recovery ofpseudohernia occurred. The recovery time for patients with complete clinical resolution ranged from 1.5 to 12 months,with a mean time of 4.9 months, and median time of 6.8 months. Associated HZinduced gastrointestinal (GI) complications were reported in 7 patients. Five patients had immunosuppressive conditions or were taking immunosuppressive medications regularly for an inflammatory condition. Our case had both pseudohernia and history of constipation. Our patient recovered completely within 6 months and gave history of constipation.

Table 1: Comparison of reported cases of post herpetic abdominal wall pseudohernia in the last 10 yrs [14].

The exact mechanism of abdominal muscle paresis following herpes zoster is poorly understood. The spread of active inflammation from the dorsal root ganglion to the anterior horn cells and involvement of the motor nerve are assumed to be involved [11,22]. Ganglionic lesions combined of the related sensory and motor roots and severe neuritis on pathological examination findings which can easily explain the clinical and electrophysiological signs [23]. The reason for this extremely rare complication is felt to be the dual innervations of musculature of abdominal wall. Symptoms of segmental muscle paresis usually appear within 2 to 6 weeks after the beginning of herpes zoster, and the involved myotomes correspond to the involved dermatomes.

Diagnosis is usually suspected byclinical evidence of HZ associated with abdominal wall or flank bulging. Physical examination shows reduced or absent reflexes. To confirm the diagnosis conduction study must be done.MRI with gadoliniumto define the extent of the inflammation,exclude local entrapment of spinal nervewhich is known to be a precipitating factors for HZ [4]. Neurophysiological examination, including EMG and DSEPs, confirms motor and sensory loss in this unusual post-herpetic complication [24].

Our case presented with pseudo-abdominal hernia along with colonic constipation. Colonic pseudo-obstruction can start before, after or even simultaneously with skin eruptions.The Enteric Nervous System may get involved due to Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV) reactivation which is a lethal process and results in different gastrointestinal tract disorders, such as idiopathic gastroparesis, chronic intestinal idiopathic pseudo-obstruction, and acute colonic pseudo-obstruction [25]. Pathogenesis is not clear. Various hypotheses have been projected to explain the origin of these factors causing segmental spasm and result in pseudo-obstruction with prominent colonic dilatation. These hypotheses are-

- Parietal and visceral peritoneal inflammation linked to vesicular eruption.

- Viral involvement of the extrinsic autonomic nervous system, either through infection of anterior horn motor neurons or by involvement of the celiac plexus ganglion .

- Direct Varicella-Zoster Virus (VZV) injury of both the ENS(Enteric Nervous System-submucosal and myenteric plexuses) and the colonic muscularis propria.

- Hemorrhagic infarction of the abdominal sympathetic ganglia as the main mechanism of the colonic pseudo-obstruction .

- VZV injury of the thoracolumbar or sacral lateral columns may interrupt sacral parasympathetic nerves and subsequently decrease intestinal contractility.

- Finally, a recent study put forward thoracic herpes zoster may prevent afferent C-fibers from facilitating gastrointestinal motility (by tachykinins), with ensuing acute intestinal pseudo-obstruction [26].

Herpetic neuralgia in a dermatomal distribution preceding the rash has long been recognized and noted to antedate the rash by up to 100 days, thereby creating significant diagnostic confusion [27]. The viral spread can involve not just the colon, but also the diaphragm, urinary tract, anus, and abdominal wall, and affect their motor activity [28].

Differential diagnosis includes lumbar hernias, that can occur through the inferior lumbar triangle of Petit or superior triangle of Grynfeelt [10].Thoracoabdominal or truncal neuropathy and lower thoracic motor radiculopathy are rare phenomena that can clinicallypresent as abdominal wall protrusions. The differential diagnosis includes diabetes, herpes zoster, intercostal nerve lesions in surgical or other thoracic procedures, thoracic disk hernia,vertebral metastasis or trauma, clinical events with involvementof abdominal organs (appendicitis or colitis) and thoracic root alteration by another etiology [29].

The overall prognosis for patients with segmental zosterparesis is generally good. According to previous studies,improvement is observed in 55%-85% of patients withsegmental herpes zoster paresis [1,30]. In a large epidemiologic study, Thomas and Howard [1] reported that 75% of patients had full recovery and the other patients showedpartial recovery 1 year from onset. Through our review and analysis of the reported cases that were followed-up, wefound that 79.3% of the patients affected had full clinical recovery of their segmental zoster abdominal paresis in 1 year, with a mean time of 4.9 months and, the remaining 20.7% had partial resolution or no recovery. Finally, 2 of the cases were associated with epidural steroid injections. The patients in these cases did not have dermatomal rash, but were confirmed serologically. The increasing age of the population and increased use of epidural steroid injection may increase the incidence of this complication of HZ [9].

Conclusion

In reality, post herpetic pseudohernia is a reversible disease with a favorable prognosis. Its diagnosis is essential to avoid unnecessary surgical intervention. A high index of suspicion is essential for diagnosis.

References:

-

- Thomas JE, Howard FM Jr. Segmental zoster paresis: A disease profile.Neurology. 1972;22:459-466.

- Chang CM, Woo E, Yu YL, Huang CY, Chin D. Herpes zoster and itsneurological complications. Postgrad Med J. 1987;85-89.

- Haanpää M, Häkkinen V, Nurmikko T. Motor involvement in acuteherpes zoster. Muscle Nerve. 1997;20:1433-1438.

- Cioni R, Giannini F, Passero S, et al. An electromyographic evaluationof motor complications in thoracic herpes zoster. Electromyogr ClinNeurophysiol. 1994;34:125-128.

- Gardner-Thorpe C, Foster JB, Barwick DD. Unusual manifestations ofherpes zoster. A clinical and electrophysiological study. J Neurol Sci. 1976;28:427-447.

- Gilden DH, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, LaGuardia JJ, Mahalingam R,Cohrs RJ. Neurologic complications of the reactivation of varicellazostervirus. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:635-645.

- Çinar N, Sahin S, Okluoglu T, Batum K, Karsidag S. Is herpes zostermerely a simple neuralgia syndrome? Eur J Gen Med. 2011;8:219-223.

- Sachs GM. Segmental zoster paresis: An electrophysiological study.Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:784-786.

- Chernev I, Dado D.(2013) Segmental zoster abdominal paresis (zoster pseudohernia): a review of the literature. PM R. 2013;5(9):786-90. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2013.05.013

- Uzma Bashir*, Muhammad Irfan Anwar, Moizza Tahir (2014) Postherpetic pseudohernia of abdominal wall: Acase report . Journal of Pakistan Association of Dermatologists. 2014;24(4):355-357.

- Safadi BY. Postherpetic self-limited abdominal wall herniation. Am J Surg. 2003;2:148.

- Broadbent WH. A case of herpetic eruption in the course of branches of the brachial plexus, followed by partial paralysis in corresponding motor nerves. Br Med J. 1886;2:460.

- Sung-Hee Kang, Ho-Kyung Song, Yeon Jang. Zoster-associated segmental paresis in a patient with cervical spinal stenosis. J International Medical Research. 2013;4(3):907-913.

- Pedro Dantas Oliveira, Paulo Vicente dos Santos Filho, Joao Eduardo Marques Tavares de Menezes Ettinger, Isabel Cristina Dantas Oliveira. Abdominal-wall postherpetic pseudohernia.Hernia. 2006;10:364-366. DOI 10.1007/s10029-006-0102-6.

- Hanakawa T, Hashimoto S, Kawamura J et al.(1997) Magneticresonance imaging in a patient with segmental zoster paresis.Neurology. 1997;2:631-632.

- Healy C, McGreal G, Lenehan B et al. Self-limitingabdominal wall herniation and constipation following herpeszoster infection. QJM. 1998;11:788–789.

- Vincent KD, Davis LS .(1998) Unilateral abdominal distention following herpes zoster outbreak. Arch Dermatol 1998;9:1168-1169.

- Zuckermam R, Siegel T.(2001) Abdominal-wall pseudoherniasecondary to herpes zoster. Hernia. 2001;2:99-100.

- Hindmarsh A, Mehta S, Mariathas DA. An unusualpresentation of lumbar hernia. Emerg Med J. 2002;5:460

- Barroso FA. Distension abdominal por Herpes Zoster.Medicina (Buenos Aires). 2002;62:53-5

- Kesler A, Galili-Mosberg R, Gadoth N. Acquired neurogenicabdominal wall weakness simulating abdominal hernia.Isr Med Assoc J. 2002;4:262-264

- Oliveira P, dos Santos Filho P, de Menezes Ettinger J, Oliveira I. Abdominal-wall postherpetic pseudohernia. Hernia. 2006;10:364-6.

- Mancuso M, Virgili M, Pizzanelli C et al.(2006) Abdominal pseudohernia caused by herpes zoster truncal D12 radiculoneuropathy. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1327.

- Santiago-Pérez S, Nevado-Estévez R, Pérez-Conde MC.(2012).Herpes zoster-induced abdominal wall paresis: neurophysiological examination in this unusual complication. J Neurol Sci. 2012;312(1-2):177-9. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2011.08.035. Epub 2011 Sep 10.

- Chen JJ, Gershon AA, Li Z, Cowles RA, Gershon .(2011)Varicella zoster virus (VZV) infects and establishes latency in enteric 276 neurons. J Neurovirol. 2011;17:578-589.

- Carranscosa MF, Sacines-Caviedes JR, Roman JG, Cano-Hoz M, Fernandez-Ayaa M, Causo-Saenz E et.al. Varicella-zoster Virus (VZV) Infection as a Possible Cause of Ogilvie's Syndrome in an Immunocompromised Host.J. Clin. Microbiol. doi:10.1128/JCM.00379-14.

- Herath P, Gunawardana SA. Acute colonic pseudo-obstruction associated with varicella zoster infection and acyclovir therapy. Ceylon Med J. 1997;42:36-37.

- Maeda K, Furukawa K, Sanada M, Kawai H, Yasuda H. Constipation and segmental abdominal paresis followed by herpes zoster. Intern Med. 2007;46:1487-1488.

- Facundo Burgos Ruiz Junior, Jullyanna Sabrysna, Morais ShinosakiWilson Marques Junior , Marcelo Simão Ferreira. Abdominal wall protrusion following herpes zoster. Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Medicina Tropical 2007;40(2):234-235.

- Tashiro S, Akaboshi K, Kobayashi Y, Mori T, Nagata M, Lui M. Herpes zoster-induced trunk muscleparesis presenting with abdominal wall pseudohernia, scoliosis and gait disturbances and its rehabilitation: A case report. Arch Phys Med rehabil 2010;91:321-325.