Bilateral Tension Pneumothorax in a Child during Laser-Assisted Supraglottic Laryngectomy: A Case Report

Salume SK1, Masood M1, Pooya D1, Reza Farahman R1, Saied A1, Aslan A2, Hossein Saidi3, Golnoosh K1, Maryam M4 and Valiollah H1*

1Department of Anaesthesiology, Pain Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

2Department of Otorhinolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, Iran University of Medical Sciences, ENT and Head & Neck Research Center and Department, Hazrat Rasoul Hospital, The five senses Institute, Tehran, Iran

3Department of Pediatric and Emergency Medicine, Hazrat Rasoul Medical Complex, Tehran, Iran

4Department of Anatomy, School of Medicine, Iran university of Medical sciences, Tehran, Iran

Received Date: 06/08/2020; Published Date: 26/08/2020

*Corresponding author: Valiollah Hassani, M.D, Professor of Anaesthesiology, Pain Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran. Tel: +989121151574; E-mail: Valiollah_hassani@yahoo.com

Abstract

We describe a case of intraoperative bilateral tension pneumothorax and diffuse subcutaneous emphysema in a child during supraglottic laser surgery. The case described was a 6-year old boy scheduled for supraglottic laser surgery due to burning-related tracheal stenosis. The patient was scheduled for operation with previous tracheostomy that ultimately led to rapidly progressive O2 de-saturation and bradycardia. The palpation of the chest wall revealed diffuse subcutaneous massive emphysema. Decreasing of breath sounds was also detected and the chest was bulged immobile bilaterally overall suspecting tension pneumothorax that was successfully managed by decompression by intercostal needling and medications for hemodynamic stability. Tension pneumothorax due to iatrogenic interventions even laser-based repairing operations is expectable, but can be successfully managed by early compensating managements.

Keywords: Pneumothorax; Child; Breath; Laser Therapy; Case Report

Introduction

Tension pneumothorax is an infrequent and life-threatening clinical condition. The overall incidence of this event remains understood, however about 1 to 3 percent of patients hospitalized especially in intensive care units or undergoing iatrogenic traumas suffer from this phenomenon [1,2]. The main causal mechanism for occurring tension pneumothorax is creating a one-way communication between the pleural cavity and lung parenchyma that result in air entrapment in the pleural cavity [3]. The major concern related to tension pneumothorax is its definitive diagnosis only based on clinical manifestations as well as early managerial approach for its removing by urgent thoracic decompression [4]. Moreover, it has been demonstrated that its inappropriate treatment may lead to devastating and irreversible consequences [5,6]. The appearance of tension pneumothorax among children may be due to different conditions such as lung parenchyma vulnerability because of using mechanical ventilation or post-end-expiratory pressure, congenital diaphragmatic hernia predisposing neonate to diaphragmatic defects followed by barotrauma and pneumothorax or Iatrogenic causes following invasive or even minimal invasive therapeutic procedures [7]. Therefore, the occurrence of tension pneumothorax is not uncommon event following trauma associated with surgical interventions, however occurrence during laser surgeries is very rare especially especially when these interventions are not related to thoracic surgery. Herein, we describe a case of intraoperative bilateral tension pneumothorax and diffuse subcutaneous emphysema in a child during supraglottic laser surgery.

Case Report

The case described was a 6-year old boy weighing 30 Kg with previous tracheostomy and tracheal stenosis due to swallow burning substances that scheduled for supraglottic laser surgery. According to the parents’ expression, he had swallowed burning substances at the age of two leading grade III esophageal burning and supraglottic stenosis that was inevitably led to gastrostomy. Three months later, esophagoscopy was performed indicating a severe esophageal stenosis with impossibility of dilatation. Due to development of respiratory distress and cyanosis, tracheostomy was indicated for the patient and 5 months later, he underwent gastric pull up surgery. During the pointed time, he was assessed regularly by laryngoscope that in the last assessment, subglottic stenosis and adhesion of base of tongue on the right side and just the gastric anastomosis orifice was discernible and on the left side it was indiscernible remains of larynx. The TVC and glottic structure were normal in retrograde fiberoptic assessment.

Figure 1: A lateral view of glottic structure and tracheostomy inserted.

The patient was scheduled for operation with previous tracheostomy. Preoperative monitoring was planned by electrocardiography and also noninvasive blood pressure and SaO2 monitoring. Following pre-oxygenation for 4 minutes, anesthesia was induced with 50 mcg fentanyle, 10 mg lidocain, 50 mg propofol and 4 mg cisatracorium . For airway assessment, a PVC endotracheal tube NO:5 was placed on the tracheostomy and correct placement of ETT was achieved after equal breath sound by auscultation. Then, cuff was filled with saline and the ETT fixed. End-tidal carbon dioxide concentration was measured. The lungs were artificially ventilated with this ventilator setting: TV=190, F= 16, I:E= 1.2, and pressure limit=25 . The anesthesia maintained with propofol 100µg/kg. Intraoperatively, the ETT was removed uneventfully repeatedly upon the request of surgeon and re-placed before decrease the SaO2. POM and EtCO2 were also monitored keeping on 35. Following laser surgery, supraglottic laryngectomy was performed with 6wat laser. During this stage of the procedure, the patient vital signs were stable. At the end of the surgery and after moving the ETT, the patient experienced rapidly progressive O2 de-saturation and despite replacement of ETT and appropriate ventilation, arterial O2 saturation did not successfully increase on manual ventilation with O2 100% 4LMP and high resistance for manual bagging was obvious. A few minutes later, bradycardia occurred and expired carbone dioxide was un-recordable. Therefore, 200 mcg Atropine in two times were administered leading insignificant improvement in cardiac rhythm followed by further hemodynamic deterioration. Unfortunately, cardiovascular arrest occurred and thus cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) began immediately. An infusion of 0.2 mg epinephrine in 3 minutes and 50 ml sodium bicarbonate were administered and the CPR lasted for 15 minutes. The palpation of the chest wall revealed diffuse subcutaneous emphysema extending to all the face, neck, thorax, abdomen, scrotom, and extremities. Decreasing of breath sounds was also detected and the chest was bulged immobile bilaterally overall suspecting tension pneumothorax.

Figure 2: Bilateral immobile bulging chest suspecting tension pneumothorax.

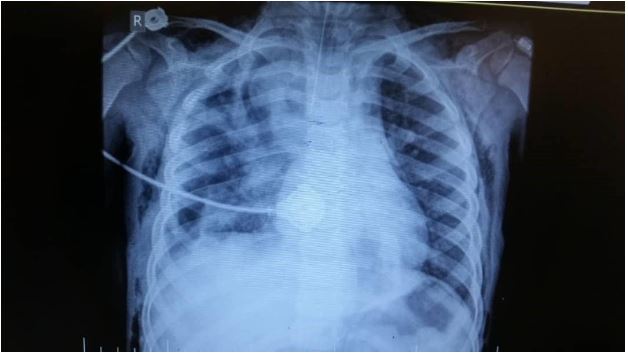

Therefore, a rapid insertion of 18 G needle in both 4-5th right and left intercostal spaces in mid-axillary line was planned that was connected to a draining system. Following this action, heart rate increased spontaneously and radial pulses were palpable, however O2 saturation did not improve significantly. So, bilateral chest tube was placed and evacuation of intrapleural air resulted in significant improvement in cardiopulmonary status. Then, manual bagging was started to effectively inflating the chest leading O2 saturation of 100% and simultaneously the rest of the vital signs were back to base line levels. Portable chest radiograph was finally performed indicating a clear condition (Figure 3). Then 100mg sodium thiopental, 4 mg dexmedetomidine, 50 mg hydrocortisone, and 20 g manitol were administrated to maintain anesthesia. The patient was then reversed with 1 mg neostigmine and 0.5 mg atropine. At the end of procedure, the patient was transformed to pediatrics intensive care unit with spontaneous breathing and was put on T-piece with FiO2=60%. After 6 hours, he was awake and obeyed but diffuse emphysema especially in face and periorbital area was still sustained. Chest tubes were removed after 7 days and patient was discharged to the ward after 12 days in a good general condition and normal arterial blood gas analysis.

Discussion

Tension pneumothorax is a mortal phenomenon which characterized by progressive hemodynamic instability such as tachycardia, hypotension, and respiratory distress. If progress or remains untreated timely, it may result in sudden cardiopulmonary collapse and sudden death, unless immediate decompression is scheduled. The main fundament of occurring tension pneumothorax is imbalance and incompatibility in air spaces in which When a one-way valve is created between the lung and the pleura, air accumulates in the pleural cavity during the respiratory cycle and the consequent increase in intrapleural pressure interferes with the effective expansion of the lung on the side of pneumothorax. Eventually, the pressure in the pleural cavity increases aggravating to lung collapse along with compensatory deviating the heart and mediastinum to other side, compressing vena cava and disturbing venous pattern and reducing cardiac output followed by mismatching ventilation-perfusion balance and therefore occurring acidosis, hypoxemia, shock and even cardiac arrest [7]. The overall incidence of tension pneumothorax is rare, but widely varies because of its wide etiological basis. According to the literature, the incidence of this event ranged widely from 0.5%–35.9% [8-10]. However, early diagnosis and immediate treatment will help the patient survive. There is not enough information about the occurrence of this incident following various types of surgery, especially laser surgery, however to the best of our knowledge, the present report is the first described occurring tension pneumothorax following supraglottic laser surgery for tracheal stenosis due to swallow burning substances in a child. However, some cases of tension pneumothorax due to iatrogenic causes have been previously presented. In a case described by Ashaal et al [11], tension pneumothorax occurred following an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography leading duodenal perforation that was successfully managed by inserting chest tube followed by laparotomy.

Figure 3: Portable chest radiograph indicating a clear condition after managing tension pneumothorax.

Al Shetawi et al [12] presented a case of intraoperative tension pneumothorax during a routine facial trauma surgery that was managed by emergency chest decompression. Gupta et al [13] also presented a case with delayed tension pneumothorax due to bronchial injury following road traffic accident that treated by surgical exploration and repair. Rahimizadeh et al in 2019 [14] described their case characterized by intraoperative tension pneumothorax during posterior vertebral column resection in a child scheduled for congenital scoliosis repairing. Finally, Freed and colleagues [15] presented a premature child suffering bronchopulmonary dysplasia that faced with tension pneumothorax due to repairing surgery-related anesthesia. Overall, tension pneumothorax can be caused by different reasons including traumatic or iatrogenic causes, but it seems that its clinical manifestation and thus managerial approaches are similar consisting immediate airways and cardiovascular decompression, establish an air pressure balance, and also hemodynamic stability.

Conclusion

Finally, it can be concluded that tension pneumothorax following surgical procedures can be fatal due to progressive compression of cardiopulmonary system unless rapid decompression of the system and Sustain the patient's hemodynamics.

Author Contributions

Sehat Kashani S., Farahmand Rad R., Mohseni M., Derakhshan P and Amniati S. contributed to the design and implementation of the research, to the analysis of the results and to the writing of the manuscript. Ahmadi A., desgined the approach of surgery. Saidi H selected the patient and analyzed the clinical data. khosravian G and Milanifard M analyzed the laboratory data and and drafting of the manuscript. Hassani V., critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References:

- Roberts DJ, Leigh-Smith S, Faris PD, et al. Clinical manifestations of tension pneumothorax: protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev. 2014;3:3.

- Ball CG, Wyrzykowski AD, Kirkpatrick AW, et al. Thoracic needle decompression for tension pneumothorax: clinical correlation with catheter length. Can J Surg. 2010;53:184-188.

- Jain A, Arora D, Juneja R, Mehta Y, et al. Life threatening tension pneumothorax during cardiac surgery. A case report. Heart Lung Vessel. 2014;6(3):204-207.

- Roberts DJ, Leigh-Smith S, Faris PT, et al. Clinical Presentation of Patients with Tension Pneumothorax A Systematic Review. Ann Surg. 2014;00:1-11.

- Rawlins R, Brown KM, Carr CS, et al. Life threatening haemorrhage after anterior needle aspiration of pneumothoraces. A role for lateral needle aspiration in emergency decompression of spontaneous pneumothorax. Emerg Med J. 2003;20:383-384.

- Riwoe D, Poncia HD. Subclavian artery laceration: a serious complication of needle decompression. Emerg Med Australas. 2011;23:651-653.

- Yoon JS, Choi SY, Suh JH, et al. Tension pneumothorax, is it a really life-threatening condition? . Journal of Cardiothoracic Surgery. 2013,8:197.

- Kim YK, Kim H, Lee CC, et al. New classification and clinical characteristics of reexpansion pulmonary edema after treatment of spontaneous pneumothorax. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;8:961-967.

- Shih CH, Yu HW, Tseng YC, et al. Clinical manifestations of primary spontaneous pneumothorax in pediatric patients: an analysis of 78 patients. Pediatr Neonatol. 2011;8:150-154.

- Kim HZ, Kim HK, Choi YH, et al. Thoracoscopic bleb resection using two-lung ventilation anesthesia with low tidal volume for primary spontaneous pneumothorax. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;8:880-5.

- Al-Ashaal Y, Hefny AF, Safi F, et al. Tension Pneumothorax Complicating Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography: Case Report and Systematic Literature Review. Asian J Surg. 2011;34(1):46-49.

- A Shetawi AH, Golden L, Turner M. Anesthetic Complication during Maxillofacial Trauma Surgery: A Case Report of Intraoperative Tension Pneumothorax. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2016;9(3): 251-254.

- Gupta A, Rattan A, Kumar S, et al. Delayed Tension Pneumothorax – Identification and Treatment in Traumatic Bronchial Injury: An Interesting Presentation. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11(9):PD12-PD13.

- Rahimizadeh A, Hassani V, Mohsenikabir N, et al. Intraoperative tension pneumothorax during posterior vertebral column resection in a child with congenital scoliosis. Surg Neurol Int. 2019;10:155.

- Freed C, Guha R. Tension pneumothorax at anaesthetic induction in an ex-premature infant with bronchopulmonary dysplasia. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012:bcr2012006386.