Management of Recurrent Cervical Cancer with Peritoneal Carcinomatosis with HIPEC

Taliya Lantsman, Marcos Lepe, Leslie Garrett, Martin Goodman, Meghan Shea

Department of Internal Medicine, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, USA

Department of Clinical Pathology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, USA

Department of Gynecologic Oncology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, USA

Department of Surgical Oncology, Tufts University School of Medicine, USA

Department of Oncology, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, USA

Received Date: 09/06/2021; Published Date: 24/06/2021

*Corresponding author: Taliya Lantsman MD, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Deaconess Building, Suite 306, One Deaconess Road, Boston, MA 02215, Phone: 203-494-8183, Fax: 617-632-8261, Email: tlantsma@bidmc. harvard.edu

Abstract

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common malignancy in woman in the world. As a significant portion of these malignancies are declining with increasing sophisticated screening, the management of recurrent cervical cancer continues to be a growing area of research. While the foundation of treatment remains with platinum-based chemotherapies, new techniques such as HIPEC has been evaluated. We present two patients with recurrent cervical adenocarcinoma with peritoneal carcinomatosis who were treated with HIPEC during de-bulking surgery with significant disease-free survival. One our patients had 15 months of disease-free survival before succumbing to her disease and the other remains disease free for over 22 months.

Keywords: Recurrent cervical cancer; HIPEC; Peritoneal carcinomatosis

Introduction

An estimated 13,170 new cases of cervical cancer are diagnosed each year in the United States, and it is the fourth most common cancer in women worldwide [1]. Squamous cell carcinomas, which account for 80% of these cancers, are declining with effective screening, though rates of cervical adenocarcinoma have risen in the last three decades. This stark difference is likely in part due to less effective identification of adenocarcinomas than squamous cell carcinomas by cervical cancer screening. While controversy exists as to which histologic type has a worse prognosis, a majority of studies demonstrate that adenocarcinomas have a higher rate of metastasis and recurrence [2]. Recurrent metastatic cervical cancer develops in 11-64% of women with cervical cancer, usually within the first two years of initial therapy completion [3]. Of these women, about 1% will have peritoneal metastasis [4]. Only a few case reports describe cervical cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis; and of those, even fewer offer feasible interventions. With few molecular targets or actionable mutations, platinum-based chemotherapies are the mainstay of treatment for recurrent metastatic cervical cancer [5,6]. However, new options have emerged to treat peritoneal carcinomatosis from gastrointestinal or other gynecologic malignancies. Hyperthermic Intra Peritoneal Chemotherapy (HIPEC) during Cyto Reductive Surgery (CRS) is one of such therapies in which high dose intraperitoneal chemotherapy is administered intraoperatively throughout the abdomen to eliminate residual microscopic cancer cells [7]. This technique uses heat to enhance the effect of intraperitoneal chemotherapy by 3 suspected mechanisms: I) heat has more toxicity for cancer tissue compared to non-cancer tissue, II) it increases the penetration of the chemotherapy, and III) it increases the cytotoxicity of the chemotherapy itself. Furthermore, when HIPEC is used in conjunction with CRS it has demonstrated more direct drug-cancer tissue contact and, in some studies, improved outcomes [8,9]. While HIPEC has been studied in abdominal malignancies, its application to gynecologic malignancies had been less studied until recently. van Driel et al demonstrated that HIPEC in advanced ovarian cancer improved recurrence free survivorship compared to non-HIPEC regimens giving rise to the implementation of HIPEC in advanced ovarian cancer [10]. In endometrial cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis, Delotte et al demonstrated safety in the implementation of HIPEC [11]. However, Heijkoop et al evaluated HIPEC in patients with cervical cancer and demonstrated poor response and survival [12]. While some of HIPEC’s results are encouraging in certain advanced gynecologic malignancies, its efficacy in cervical cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis remains undefined. Here, we present two cases of patients with recurrent cervical cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis who underwent HIPEC. Unfortunately, neither of these patients qualified for clinical trials at our institution at the time that they underwent HIPEC for recurrent cervical cancer. To our knowledge, these are the only cases in the literature that describe the use of HIPEC in recurrent metastatic cervical adenocarcinoma with peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Case Presentation

Our first case is a 35-year-old woman who was first diagnosed with stage 1B1 endocervical adenocarcinoma and underwent robotic assisted radical hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy followed by surveillance. Her surveillance was notable for physical exams in a facility closer to her home. She underwent PET scan 4 months after resection which was negative for disease recurrence. 10 months later, she presented with abdominal bloating and was found to have an abdominal mass with peritoneal carcinomatosis and malignant ascites without disease in her chest. She was initiated on carboplatin/paclitaxel/bevacizumab for 6 cycles [13]. Notably she received carboplatin instead of cisplatin due to anaphylaxis to fosaprepitant. Her genomic testing demonstrated no actionable alterations though identified ARID1A mutation, PIK3CA mutation and PTEN mutation, also of note her tumor was microsatellite stable and the tumor mutational burden low. She had a significant partial response to chemotherapy with resolution of symptoms and ascites though a persistent pelvic mass. She then underwent cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC with cisplatin and paclitaxel. Disease was resected via omentectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, appendectomy, and removal of intra-abdominal tumor that was greater than 10 cm. Once all the disease was removed, 3 liters of plasmalyte were instilled and circulated at 1400mL/minute. Once temperatures were between 42-43C, cisplatin 100mg/m2 and paclitaxel 175mg/m2 was instilled. The abdomen was agitated for 90 minutes and then all the fluid was removed via outflow catheters. Following HIPEC, she completed 3 more cycles of carboplatin/paclitaxel. She then transitioned to bevacizumab maintenance for 13 cycles. She is currently in surveillance with CT imaging and exams every 3 months and remains without evidence of disease 24 months since HIPEC therapy.

Our second case is a 33-year-old woman who was first diagnosed with stage IA1 cervical adenocarcinoma. The patient underwent cold knife conization with multiple local recurrences. During her course, she received a total of 4 cold knife conizations in attempts to preserve fertility. Three years after diagnosis with stage 1A1 cervical adenocarcinoma with positive endocervical curettage and deep endocervical margins, the patient underwent total laparoscopic hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy followed by adjuvant chemoradiation with cisplatin given high risk feature of close margins. She started on a surveillance regimen with exams every three months. Unfortunately, 16 months into surveillance, the patient presented with abdominal distension and pain. CT torso demonstrated large volume ascites with extensive peritoneal nodularity and omental caking without evidence of disease in her chest. She underwent diagnostic laparoscopy and omental biopsy where pathology confirmed recurrent cervical adenocarcinoma. She received cisplatin/paclitaxel/bevacizumab for 6 cycles with significant partial response yet had residual peritoneal carcinomatosis. Her genomic testing sequencing from tumor resection demonstrated genomic alterations in FANCC, MLL2 and SMAD4. Microsatellite status and tumor mutation burden could not be determined. After a failed attempt to qualify for an immunotherapy clinical trial due to the adenocarcinoma histology, she received an additional cycle of paclitaxel and bevacizumab and then underwent cytoreductive surgery with HIPEC. She underwent cholecystectomy, appendectomy, splenectomy, omentectomy, bilateral oophorectomy and right sided peritoneal stripping. Once all visible disease was removed, 3 liters of plasmalyte was instilled with fluid circulation at 1500mL/minute until fluid temperature reached 42-43C. Then, 30mg mitomycin-C and 75mg/m2 cisplatin were instilled. Patient received sodium thiosulfate as a bolus and then as a continuous drip for 6 hours per weight-based protocol. 60 minutes into the instillation, the patient received another 10mg of mitomycin-C. During this time, the abdomen was agitated. All the fluid was drained via outflow catheters after 90 minutes. She did not receive any adjuvant therapy following HIPEC. Surveillance consisted of CT/MRI imaging and exam every 3 months. She remained disease free for 15 months from time of HIPEC. Unfortunately, she developed biliary disease as demonstrated on CT torso: new metastatic infiltrative mass/lymph node involving the hepatic hilum causing moderate intrahepatic biliary ductal dilation and a new focus of peritoneal carcinomatosis. She was started on cisplatin/bevacizumab given the platinum free interval; however, she had progression of disease and then treated with nivolumab/ipilimumab with initial response but then further disease progression. She ultimately passed away over 3 years from her initial diagnosis of recurrent metastatic disease.

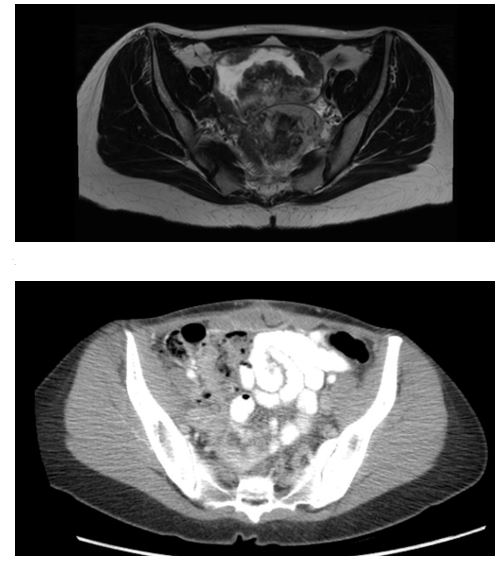

1st Patient Pre and Post CRS/HIPEC

Figure 1: An MRI transverse cross section, prior to CRS/HIPEC, of a bilobed 13.6cm pelvic mass with small discrete enhancing nodules in the right lower quadrant representing metastasis. Image 2 is a CT transverse cross section demonstrating no evidence of disease recurrence.

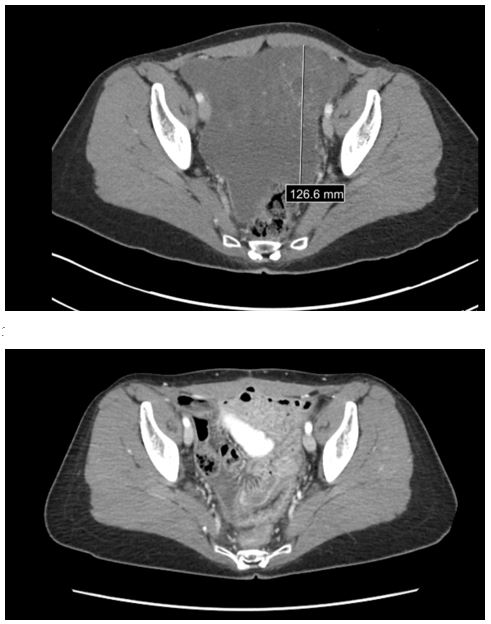

2nd Patient Pre and Post CRS/HIPEC

Figure 2: A CT transverse cross section, prior to CRS/HIPEC, of a mass occupying the pelvis with peritoneal thickening. Image 2 is a CT transverse cross section, post CRS/HIPEC, with no mass and resolved peritoneal thickening and no signs of metastasis.

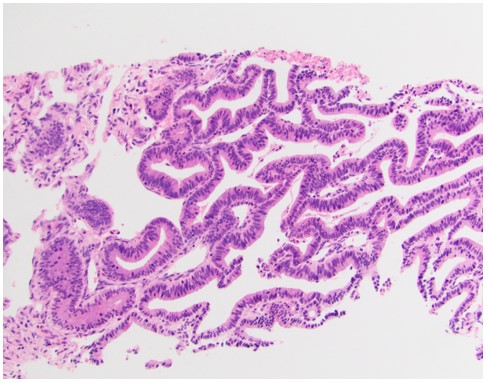

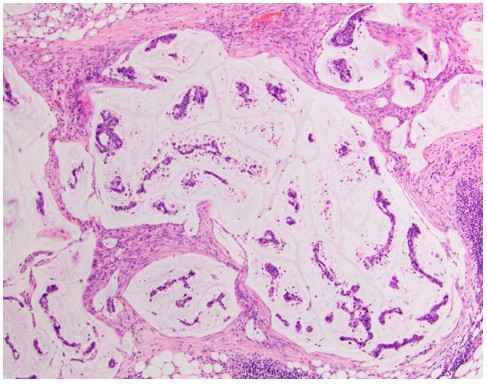

Pathology

Figure 3: An H&E stain of the pelvic mass from patient 1 taken prior to CRS/HIPEC consistent with cervical adenocarcinoma. Image 2 is an H&E stain of an omental biopsy from patient 2 taken prior to CRS/HIPEC demonstrating cervical adenocarcinoma.

Discussion

In both of these cases, these women presented with cervical adenocarcinoma with isolated abdominal recurrences with peritoneal carcinomatosis after minimally invasive hysterectomy. Based on the conclusions drawn in the LACC trial, our patients were perhaps at higher risk for locoregional recurrence because they underwent minimally invasive surgical hysterectomy [14]. Nevertheless, given the rarity of such a presentation, few protocols for recurrent cervical cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis exist. Much of the management of recurrent cervical cancer with abdominal metastases was extrapolated from pathways in advanced ovarian carcinoma. While Heijkoop et al’s study follows 38 patients with locally advanced cervical cancer, their findings may be less applicable to our patients. First, their study does not specifically target patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Furthermore, our HIPEC protocols greatly differed from that used in Heijkoop et al. Lastly, only 4 of the 38 patients in Heijkoop et al had adenocarcinoma of the cervix as those in our case report. The use of HIPEC in peritoneal carcinomatosis continues to be an area of intense research with no single regimen. In particular, the use of bevacizumab around the time of HIPEC and cytoreductive surgery remains controversial. While King et al demonstrate that bevacizumab is not associated with increased morbidity or mortality following CRS/HIPEC, Eveno et al demonstrate that administration of bevacizumab before CRS/HIPEC results in twofold increased morbidity [15-16]. Lastly, the significant disease reduction after HIPEC must be considered in the setting of significant cytoreductive surgery. These two cases of recurrent cervical cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis with remission after CRS/HIPEC incite further questions regarding the appropriate timing and candidacy for HIPEC.

Consultation

These two cases of recurrent cervical cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis with use of HIPEC during de-bulking surgery with significant disease survival, 15 months and 22 months respectively, demonstrate a possible role for HIPEC in for this disease presentation that does not have many treatment options other than platinum-based therapy. This opens the door to further investigation of HIPEC in patients with cervical cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis.

Declaration of Competing Interests

The authors whose names are listed certify that they have NO affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria; educational grants; participation in speakers’ bureaus; membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

Author Contribution

Taliya Lantsman MD: original draft, review and editing

Marcos Lepe MD: Pathology evaluation

Leslie Garrett MD, Meghan Shea MD, Martin Goodman MD: conceptualization, methodology, writing-review and editing

References

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network. (2021). Cervical cancer (version 1.2021).

- Gien LT, Beauchemin MC, Thomas G. Adenocarcinoma: a unique cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2010; 116(1):140-146.

- Boussios, S., Seraj, et al (2016). Management of patients with recurrent/advanced cervical cancer beyond first line platinum regimens: Where do we stand? A literature review. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 2016; 108, 164-174.

- Burg L, Timmermans M, van der Aa M, Boll D, Rovers K, de Hingh I, et al. Incidence and predictors of peritoneal metastases of gynecological origin: a population-based study in the Netherlands. J Gynecol Oncol. 2020; 31(5): e58. doi: 10.3802/jgo.2020.31.e58. PMID: 32808491; PMCID: PMC7440978.

- Chao A, Lin CT, Lai CH. Updates in systemic treatment for metastatic cervical cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2014; 15(1): 1-13. doi: 10.1007/s11864-013-0273-1. PMID: 24429797.

- Orgiano L, Pani F, Astara G, Madeddu C, Marini S, Manca A, Mantovani G. The role of "closed abdomen" hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) in the palliative treatment of neoplastic ascites from peritoneal carcinomatosis: report of a single-center experience. Support Care Cancer. 2016; 24(10): 4293-4299. doi: 10.1007/s00520-016-3262-7. Epub 2016 May 12. PMID: 27169699.

- Sugarbaker PH. New standard of care for appendiceal epithelial neoplasms and pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome? Lancet Oncol 2006; 7: 69–76

- Bendifallah S, de Foucher T, Bricou A, Ouldamer L, Lavoue V, Varinot J, et al. Groupe de Recherche FRANCOGYN, FRANCE. Cervical cancer recurrence: Proposal for a classification based on anatomical dissemination pathways and prognosis. Surg Oncol. 2019; 30: 40-46. doi: 10.1016/j.suronc.2019.05.004. Epub 2019 May 23. PMID: 31500783.

- Glehen O, Gilly FN, Boutitie F, et al. Toward curative treatment of peritoneal carcinomatosis from nonovarian origin by cytoreductive surgery combined with perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy: a multi-institutional study of 1,290 patients. Cancer. 2010; 116(24): 5608-5618. doi:10.1002/cncr.25356

- Driel, W, et al. “Hyperthermic Intraperitoneal Chemotherapy in Ovarian Cancer.” New England Journal of Medicine, vol. 378, no. 14, May 2018, pp. 1362–1364. doi:10.1056/nejmc1802033.

- Delotte J, Desantis M, Frigenza M, Quaranta D, Bongain A, Benchimol D, et al. Cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for the treatment of endometrial cancer with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2014; 172: 111-114. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.10.026. Epub 2013 Nov 5. PMID: 24300558.

- Heijkoop ST, van Doorn HC, Stalpers LJ, Boere IA, van der Velden J, Franckena M, Westermann AM. Results of concurrent chemotherapy and hyperthermia in patients with recurrent cervical cancer after previous chemoradiation. Int J Hyperthermia. 2014; 30(1): 6-10. doi: 10.3109/02656736.2013.844366. Epub 2013 Oct 24. PMID: 24156619.

- Tewari KS, Monk BJ. Evidence-Based Treatment Paradigms for Management of Invasive Cervical Carcinoma [published correction appears in J Clin Oncol. 2019; 37(31): 2956. J Clin Oncol. 2019;37(27):2472‐2489. doi:10.1200/JCO.18.02303

- King BH, Baumgartner JM, Kelly KJ, Marmor RA, Lowy AM, Veerapong J. Preoperative bevacizumab does not increase complications following cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. PLoS One. 2020; 15(12): e0243252. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243252. PMID: 33270763; PMCID: PMC7714141.

- Eveno C, Passot G, Goéré D, Soyer P, Gayat E, Glehen O, et al. Bevacizumab doubles the early postoperative complication rate after cytoreductive surgery with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for peritoneal carcinomatosis of colorectal origin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014; 21(6): 1792-1800. doi: 10.1245/s10434-013-3442-3. Epub 2013 Dec 15. PMID: 24337648.