How to Write Up and Publish Novel Research

Andrew Macnab*

Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Canada and the Stellenbosch Institute for Advanced Study (STIAS), Wallenberg Research Center at Stellenbosch University, South Africa

Received Date: 05/11/2022; Published Date: 23/11/2022

*Corresponding author: Andrew Macnab, Department of Pediatrics, University of British Columbia, Canada. Email: ajmacnab@gmail.com

Introduction

There are many reasons to write a case report or contribute a scientific paper.

Your reason ‘why’ will be personal and uniquely yours. You may well have seen a case where you identified something useful to share with others that could lead to an advance in clinical practice or suggests a new avenue for research. Alternatively, you may have had an innovative idea, discovered new information of importance, or found a better way to do something through novel research. For many of you there is an expectation that you ‘publish’ as part of your career path in your profession. Whatever the reason, knowledge transfer through peer reviewed publication is a integral part of the advancement of science, so many of us find ourselves faced with the task of writing a paper and submitting it for publication.

How to start a paper

The general formula that most scientific papers follow, and the sections that make up an informative case report or case series, are described in literature that can be found on a Google search; helpful examples include a book by Hall [1]. Those of you new to writing are well advised to read other authors’ work, to find a style and way of writing you like. You can use these papers as a model to help you get started, but do not, of course, copy the work of others, as doing so is plagiarism and completely unacceptable [2].

Ask colleagues you respect if the case that interests you has educational value that makes it suitable for publication, or for advice on what aspects of your research are original, and get their ideas and practical help on how to start to write. A ‘litmus test’ for the potential of both types of report is do you have rare or unusual information to include and things your readers can learn from being taken through the decision making processes followed.

Before starting to write, I recommend my practice of reading papers in the journal in which I think my work could be published. Each journal has a number of different types of paper it publishes. These range from original/scientific reports, through review articles and commentaries, to case reports, clinical images, case studies, technical updates and letters to the editor; one less typical format is the ‘photo-essay.’ In such essays, a series of photos are used as the principal medium for sharing information; each photo is accompanied by an explanatory caption, and linked together by short sections of text, followed by selected references [3]. Each journal also has its own requirements for formatting and content that define its style, so it is essential to read the journal’s ‘Guidelines for Authors’ to get detailed instructions on all aspects of how to set out your paper; these are available on line.

The anatomy of a successful scientific paper and a shorter case report is generally similar:

Title: Keep the title short; it should be a simple description of the content of your paper. Make sure it is not so technical it cannot be easily understood. Do not make your title a question.

Abstract: This provides a concise overview that summarizes your paper. Stay within the journal’s word limit; is a ‘structured’ abstract required? Even if not, most abstracts are still best written to include the sections a formally ‘structured’ abstract requires, but omit the headings: Introduction/Background, Materials/Methods, Results, and Conclusion.

Keywords: A short list of terms is usually asked for; these keywords are used to index and drive searches that will connect others with your work. Do not repeat words included in your paper’s title; these will become part of the search terms automatically.

Introduction: Briefly state what your publication is about, and introduce relevant literature to provide background (what is known/unknown). Describe what your contribution is intended to add (the knowledge gap it fills). When writing a scientific paper, ideally you should state a hypothesis (or specific research question) in the introduction, and at the end of the section describe how it was tested/studied.

Materials/Methods: This section is intended to enable an experiment or scientific study you are reporting to be repeated by anyone who wishes to do this, so it must include 'What' you did, 'How' you did it (including how you analysed your data), 'Why' you did things in the way that you did, 'Who' took part (the population), and 'Where' and 'When' it was done. (These are the six terms recommended by Asher [4], that really help to make sure all the detail required is included in the framework of a scientific paper); Asher was well known for writing very clear and interesting reports and papers.

Results: This section is for your data (e.g. the details (demographics) and number of participating subjects), and the findings from the tests and analyses done (what you found out). Be objective and use statistics for support. Use tables with numeric data and graphs/bar charts more than words. Include here brief details of the ethical approval you received for your study. This is NOT the place to describe what your results mean. Check to make sure your math is correct (e.g. percentages add up to 100). Provide clear captions for each figure and table.

Discussion: Start with a short paragraph that summarizes your paper. (What new knowledge are you reporting, what did you find out that differs from prior cases/research, did you prove or disprove a hypothesis). Then follow with interpretation of each of your (major) findings, put in context through reference to other studies, cases or opinions (described in one or two sentences and cited carefully). Remember that discussing the elements of your case or research findings that are unusual is valuable, as is offering an explanation for aspects that are unexpected. Include a paragraph describing the ‘Limitations’ of your study or what you report. Would your case have benefited from additional elements of history or outcome, or results from tests that were not conducted. In your research, what you could have done better (e.g. more study subjects) or would have done differently had it been possible (e.g. using a validated evaluation method, having longer follow up or by asking additional questions). Finally, state the learning point(s) from what you are reporting, suggest what might be done in future following your research or how a similar case could be managed differently.

Conclusion: This should be a few sentences that give the reader the ‘take away’ message of your paper (the implications of what you are writing about). If the ‘Guidelines for Authors’ do not ask for a separate Conclusion, it is good to include these sentences as the concluding sentences at the end of your Discussion.

References: Pay attention to the format required by the journal (e.g. Vancouver style, APA or Chicago) and any limit to the number of references allowed. Use up to date citations. Accurately cite the source of all key statements/research you discuss (including contradictory studies).

Acknowledgements: Check you have included details of any financial/practical support you received for your research, stated your compliance with ethical guidelines where applicable [2] and included a statement regarding conflict of interest.

Before you submit

Spell check what you have written. Have someone read your report as if they were a reviewer so you can make appropriate additions/deletions. Read through a printed copy of your final version (several times) as this avoids errors missed when editing ‘on screen.’ Make sure the names of co-authors are spelled correctly, and the affiliations and contact information required are provided. Have all co-authors read and approve the final version. If you possibly can, have an English editor read through your manuscript; this will help you avoid errors with your grammar, spelling and punctuation, and identify any places where the meaning of what you have written is unclear. Care like this before submission makes a positive review more likely.

Submission

Follow the online submission instructions (each journal is different) Give yourself time to complete all the required sections carefully. Are Tables, Figures, Captions required as separate files? Is the submission to be ‘blinded’? Is a 'Cover letter’ required? Are you asked to suggest possible reviewers for your paper?

Rejection

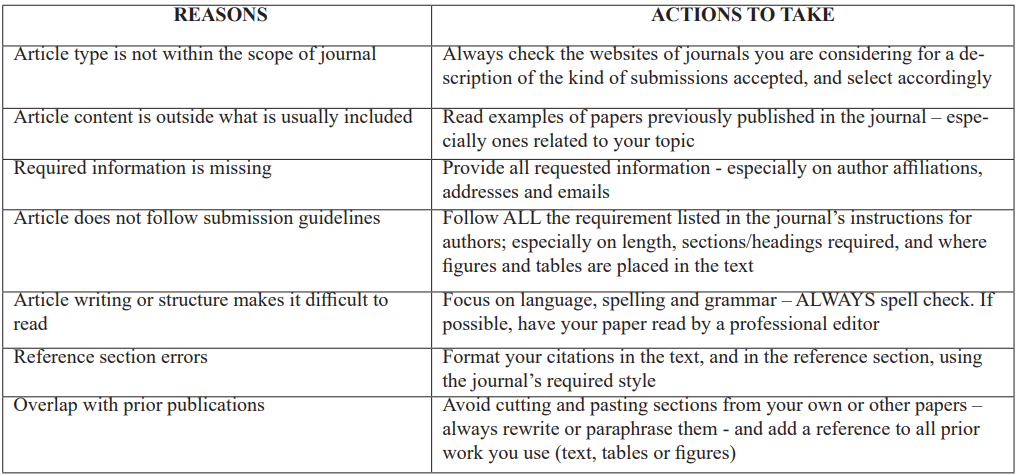

Some articles are returned by journal staff without peer review. Common reasons for this happening, and how you can do your best to avoid rejection at this stage are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Why your paper may not be sent for peer review, and what to do about it

Peer Review

Following peer review, the editor will send you a decision with the reviewer’s comments – it often takes many weeks for this to occur. The editorial decision may be acceptance for publication, or rejection, or the offer to resubmit. Resubmission usually involves either a major or minor revision. Look at the decision and reviewer’s feedback with your co-authors/supervisor. Try and view the changes suggested as a way to improve your paper, and work to respond to them as soon as you can – delay in responding risks your paper going unpublished.

Resubmission

If the journal editors say they will consider a revised version of your paper, write a response letter outlining the changes/additions/deletions/edits you have made; explain any of the comments/suggestions that you cannot respond to, OR feel are not appropriate. The editor’s invitation to resubmit is not a promise of publication, but your chance that it will be accepted are much greater if you work to improve your paper. What ever happens, re-submit your revised manuscript promptly. Hopefully you will be invited to do this to the same journal you submitted to originally, but if you are not given this option because your submission was rejected, do not be discouraged, identify another suitable journal and send your revised and improved paper there.

Article proofs

Once accepted, the journal’s editorial staff will edit and format your paper to conform with the journal’s style and language preferences, and send you a proof called a ‘galley’ [5]. This is an important final step before publication where you need to respond to any queries identified by the editorial staff, and have one more chance to check your work for errors. So read the proofs ‘word for word’ and identify where corrections are needed. This is NOT an invitation to re-write your paper but it is your final chance to ensure your work is correct. Update any citations ‘in press’ at the time of submission and check all author names and affiliations. Sometimes the editing process changes your intended meaning; more often you will find errors like ‘typos’ that have slipped through your earlier checks. Corrections to proofs are ‘time sensitive’ so attend to them promptly and return your response within the allowed timeline to avoid delaying publication of your paper.

Key points

Writing up an interesting case or a paper reporting novel research takes time and effort, but the process becomes more straightforward if you follow the established guidelines; remember Asher’s six words for framing your manuscript, and, include the elements required in each section of the paper.

Whatever paper you write, the Abstract and Conclusion are the sections that will be read most; we all hope any paper we write will be read from beginning to end, but in today’s world that rarely happens. But never-the-less your abstract will ensure your ‘message’ can be shared with a wide audience, as, once your paper is published, the abstract will be available on multiple platforms such as Google Scholar. Then those who want to know more about your work can access your full paper.

In a research paper, remember that it is the Methods section that contains the most important information. This is because a clear and full description enables others to understand and interpret what was done, and also makes it possible for your study to be repeated by anyone wishing to do so in the future, if new knowledge or techniques make doing so relevant. We all like to think that our results and how we interpret them are the most valuable part of any paper we write; however, as science and knowledge advance, what we have written and concluded today may well prove to be limited or wrong in the future, but the method you chose to follow can be used again if it is fully and clearly described.

Preparing a scientific paper or writing up a case is best not done alone. Gather ideas, thoughts and encouragement from your colleagues and invite them to work with you as co-authors. Then have someone not connected with the work you have done read what you have written to make sure it is easy to understand (and interesting). We all learn from reading papers other authors have written, and, as authors, we learn again from the feedback we receive through reviewer’s comments and suggestions.

When your paper is published, remember to pause and celebrate your success, as being published is an achievement, and only happens after a lot of hard work. Then, once you are an author, keep writing, and remember that you now have the experience required to act as a mentor to the friend or colleague who asks you, “How do I write up and publish my scientific research?”

References

- Hall GM. (Ed.). How to write a paper. John Wiley & Sons. 2012.

- Masic I, Hodzic A, Mulic S. Ethics in medical research and publication. Int J Prev Med, 2014; 5(9): 1073.

- Asher R. Six honest serving men for medical writers. JAMA, 1969; 208(1): 83-87.

- Macnab AJ, Mukisa R, Stothers L. The use of photo-essay to report advances in applied Health. Global Health Management Journal, 2018; 2(2): 44-47.

- Romain PL. Conflicts of interest in research: looking out for number one means keeping the primary interest front and center. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med, 2015; 8(2): 122-127.

- https://www.enago.com/academy/galley-proofs-the-final-step-before-manuscript-publication/ (accessed November 5 2022)