Rate of Successful Intubation in Critically Ill Patients, without Utilizing a Paralytic Agent, an Urban Community Hospital Experience

Nabil Mesiha, Kunal Nangrani*, Yoonsun Mo, Jaclyn Connors, John Zeibeq and James Gasperino

The Brooklyn Hospital Center Division of Pulmonary Medicine and Division of Critical Care Medicine, Brooklyn, New York, USA

Received Date: 04/07/2022; Published Date: 13/07/2022

*Corresponding author: Kunal Nangrani, The Brooklyn Hospital Center Division of Pulmonary Medicine and Division of Critical Care Medicine, Brooklyn, USA

Abstract

Purpose: To determine the frequency of optimal intubation conditions in crash airways without the use of paralytic agents in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) settings.

Methods: This is a single center, prospectively collected, retrospectively analyzed, observational cohort study of all endotracheal intubations performed by a critical care team at an urban community teaching hospital from January 1st, 2019, to January 1st, 2020. The primary outcome was overall intubating conditions based upon a validated scoring system without the use of paralytic agent. Other data points collected include patient demographics, indication for intubation, patient comorbidities, size of the endotracheal tube, and number of intubation attempts.

Results: A total of 207 patients underwent an emergency endotracheal intubation during the above period and after filtering patients for exclusion criteria we were left with a total of 195 patients. The most common reason for intubation in our patient population was acute hypoxic respiratory failure (N=103, 52.8%) followed by altered mental status (N=99, 50.8%). Overall, 88.2% of patients (N=172) were determined to have an intubation grade of good or excellent. We were able to achieve first-pass success in 80% of the patients without utilizing a paralytic agent. We were able to achieve good or excellent intubation conditions in majority of our patient’s (N=137, 70.2%) utilizing 2 or less induction agents.

Introduction

Emergency airway management outside of the Operating Room (OR) is a considered high-risk procedure with complications, such as severe hypoxemia, hemodynamic collapse, cardiac arrest, and death, occurring in more than half of patients [1- 5]. Rapid sequence intubation (RSI) with the use of paralytic agents is a commonly used strategy to maintain high first-pass success of tracheal intubation [4-7]. However, paralytic agents carry a risk of loss of potential for preoxygenation with bagvalve-mask devices, which can lead to detrimental outcomes in a patient who already has ventilation-perfusion mismatch [5].

Additionally, in patients with anatomically difficult airway, utilization of paralytic agents can lead to prolonged period of apnea or even cardiopulmonary arrest while awaiting a reversal agent or inability to secure a surgical airway [5]. Limited studies are available evaluating intubation conditions during emergency endotracheal intubation without the use of paralytic agents. This becomes more challenging in a crashing intensive care patient. 8 The authors have observed that the optimal intubation conditions can be achieved without the use of paralytic agents during emergent airway management performed by critical care physicians. The purpose of this study is to determine the frequency of optimal intubation conditions in crash airways without the use of paralytic agents in Intensive Care Unit (ICU) settings.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a single center, prospectively collected data and retrospectively analyzed, observational cohort study of all endotracheal intubations performed by critical care team in an urban community teaching hospital from January 1, 2019 to January 1, 2020. This project was overseen by board certified physicians rounding in ICU and critical care outreach teams at our hospital. Emergency endotracheal intubation were performed by pulmonary critical care fellows under the direct supervision of attending physicians without the use of paralytic agents during intubation given the previously mentioned risks. This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB ID # 1210924-1).

Brooklyn Hospital Center is a 464-bed community-based hospital, providing medical, pediatric, surgical, obstetrics-gynecology services both in outpatient and inpatient settings. Our ICU covers both medical surgical patients. The outreach service is composed of critical care attending, pulmonary critical care fellows, medical residents and pharmacy residents who provide 24-hour coverage for inpatient medical emergency of admitted patients. This includes rapid responses, code blues and intake of patients into ICU. All data was collected by a Pulmonary Critical Care fellow.

Study Population

Patients included in this study were older than 21 years of age who required an emergent endotracheal intubation during their index hospitalization. The intubation was performed by the pulmonary critical care fellow or critical care attending during the above specified time frame. Patients were excluded from this study if intubation was performed by anyone other than a pulmonary critical care team. Patients were also excluded if they were given a paralytic for intubation or if patients required endotracheal intubation post cardiac arrest, or pregnant patients.

Data Collection and Study Outcomes

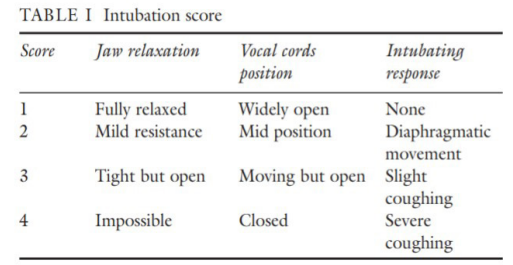

The primary outcome was overall intubating conditions based upon a validated scoring system which assessed jaw relaxation, vocal cord position, and response to intubation (Figure 1) (9, 14). An intubation score of < 3 is considered excellent, a score of 4 to 6 is considered good, and a score of > 7 is considered inadequate. Secondary outcomes included type of sedative used, frequency of sedative agents used, changes in hemodynamics following intubation, and vasopressor requirements following intubation. Additional data collected included patient demographics, the unit where the intubation was performed, indication for intubation, patient comorbidities, size of the endotracheal tube used, number of intubation attempts, and whether a rescue airway or paralytic agent was ultimately required.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics such as mean with standard deviation and median with interquartile range were used to analyze demographic data, baseline characteristics, and intubation quality. A paired t-test was used to compare pre- and post-intubation hemodynamic parameters and Mann Whitney U was used to compare median vasopressor doses. A p-value of <0.05 was considered significant.

Figure 1: Scoring system to determine the ease of intubation.

Adapted from “A combination of alfentanil-lidocaine-propofol provides better intubating conditions than fentanyllidocaine-propofol in the absence of muscle relaxants” by Jabbour-Khoury SI, Dabbous AS, Rizk LB, Abou Jalad NM, Bartelmaos TE, El-Khatib MF, Baraka AS. Can J Anaesth. 2003 Feb;50(2):116-20. doi: 10.1007/BF03017841. PMID: 12560299.

Results

A total of 207 patients with age ranging from 24 to 88 years (average age of 66) underwent emergency endotracheal intubation by the critical care team during the specified time frame were included in this study. Four patients required paralytics use and were eventually excluded from final analysis. Also excluded were eight patients who were intubated post cardiac arrest, leaving with a total of 195 patients. Demographics and baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. The most common reason for intubation in our patient population was acute hypoxic respiratory failure (52.8%) followed by altered mental status (50.8%). More than half of the patients (52.8%) were intubated in the intensive care unit followed by the emergency department (ED) (23.6%).

Table 1: Patient characteristics.

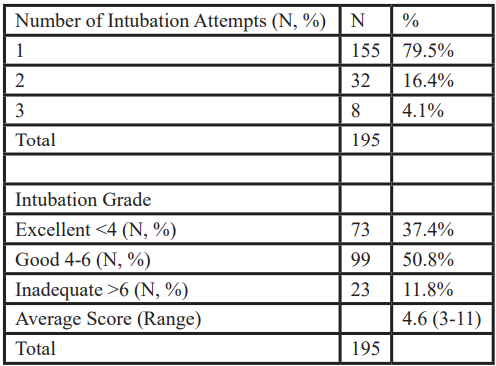

Overall, 88.2% of patients were determined to have an intubation grade of good or excellent at the time of the evaluation (Table 2). First-pass success was achieved in 80% of the patients.

Table 2:

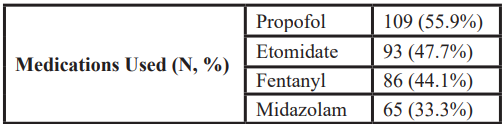

Majority of our patients (81%) required two or less induction agent to achieve good or excellent condition for intubation. Propofol (55.9%) at a median dose of 0.88 mg/kg (IQR 0.55- 1.39) was the most frequently used sedative agent, either alone or in combination with etomidate (47.7%) (0.27 mg/kg, IQR 0.22-0.31), fentanyl (44.1%) (1.37 mcg/kg, IQR 1.05-1.59), and/or midazolam (33.3%) (0.055 mg/kg, IQR 0.043-0.069). The use of a specific induction agent in isolation or combination did not appear to largely affect the intubation conditions (Table 3). Overall, we were able to achieve a first pass success in 155 patients (80 %).

Table 3:

Table 4:

Mean arterial pressure (MAP) decreased following intubation from an average of 94 mmHg to 86 mmHg (Table 4). A total of 51 patients (26.2%) were started on vasopressor; however, 20 of them were started on vasopressors pre-emptively and were tapered off within 24 hours. A total of 144 (73.8%) patients never required vasopressor support. Overall, the median dose of vasopressors was not significantly changed following intubation (p = 0.6599).

Discussion

The present study found that most patients were successfully intubated on the first attempt with a good or excellent intubation grade without the use of paralytic agents when emergency airway management was required. Also important is to recognize that good to excellent conditions were obtained in majority of patients with utilization of two or less sedative medications. Although a slight decrease in MAP was noted following intubation, this did not lead to utilization of vasopressors or increased dose of vasopressors in patients. Additionally, the doses of sedative agents used in our study were frequently lower than what has been described in literature for non-critically ill patients and when used as a part of RSI [10]. It is possible this lower dosing strategy affected not seeing a significant change in vasopressor requirements following intubation.

Although the use of paralytic agents has been shown to improve intubation conditions in the surgical and emergency department settings, few studies have been conducted in the emergency airway management outside these settings [4,6-8]. The patients who required emergency airway management have a few notable differences from patients being intubated in the surgical setting, including frequent pre-existing hypoxemia, hemodynamic instability, vasopressor support, which can be exacerbated by the intubation attempt and potentially lead to mortality if the airway is unable to be secured upon the initial attempt1-5. Despite our patient population falling within the higher risk category, the present study using no paralytics during emergency endotracheal intubation demonstrated similar outcomes compared to studies published from the National Emergency Airway Registry with close to 80% of patients achieving first-pass success rates and greater than 99% of airways successfully secured [6].

This study is subject to some limitations. First, while good or excellent intubation conditions were achieved without the use of a paralytic in most of our patients, clinical outcomes were not compared with ICU patients who underwent emergency endotracheal intubations with paralytics.

Conclusion

Satisfactory intubation conditions were achieved in ICU patients who underwent emergency endotracheal intubations on the initial attempt without the use of paralytic agents and without frequently requiring the addition of vasopressors. Even though these patients were hemodynamically unstable prior to intubation, majority of them did not see an increased in vasopressor demand, noting that although changes in hemodynamics were statistically significant, they did not have a practical impact. Future studies are needed to compare clinical outcomes among the different pre-intubation medications, especially with or without the use of paralytics, to determine which specific agent(s) would be best for this patient population.

References

- Divatia JV, Khan PU, Myatra SN. Tracheal intubation in the ICU: Lifesaving or life threatening? Indian J Anaesth, 2011; 55(5): 470-475. DOI: 10.4103/0019-5049.89872

- Heuer JF, Crozier TA, Barwing J, et al. Incidence of difficult intubation in intensive care patients: analysis of contributing factors. Anaesth Intensive Care, 2012; 40: 120-127.

- Lapinsky SE. Endotracheal intubation in the ICU. Crit Care, 2015; 19: 258-260. DOI: 10.1186/s13054-015-0964-z.

- Martin LD, Mhyre JM, Shanks AM, et al. 3,423 Emergency Tracheal Intubations at a University Hospital: Airway Outcomes and Complications. Anesthesiology, 2011; 114: 42-48. DOI: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e318201cc415

- Umobong EU, Mayo PH. Critical Care Airway Management. Crit Care Clin, 2018; 34: 313-324.

- Brown CA, Bair AE, Pallin DJ, et al. Techniques, Success, and Adverse Events of Emergency Department Adult Intubations. Ann Emerg Med, 2015; 65(4): 363-370. e1. DOI: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.10.036

- Lundstrom LH, Duez CH, Norskov AK, et al. Effects of avoidance or use of neuromuscular blocking agents on outcomes in tracheal intubation: a Cochrane systematic review. Br J Anesth, 2018; 120(6): 1381-1393. DOI: 10.1016/j.bja.2017.11.106

- Gehrke L, Oliveira RP, Becker M, Friedman G. Diazepam or midazolam for orotracheal intubation in the ICU? Rev Assoc Med Bras, 2015; 61(1): 30-34. DOI: 10.1590/1806-9282.61.01.030.

- Jong AD, Molinari N, Terzi N, et al. Early Identification of Patients at Risk for Difficult Intubation in the Intensive Care Unit: Development and Validation of the MACOCHA Score in a Multicenter Cohort Study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med, 2013; 187(8): 832-839.

- Sivilotti ML, Filbin MR, Murray HE, et al. Does the Sedative Agent Facilitate Emergency Rapid Sequence Intubation? Acad Emerg Med, 2003; 10(6): 612-620.

- Brown W, Santhosh L, Brady AK, et al. A call for collaboration and consensus on training for endotracheal intubation in the medical intensive care unit. Crit Care, 2020; 24: 621. DOI: 10.1186/s13054-020-03317-3.

- Mort TC. Emergency tracheal intubation: complications associated with repeated laryngoscopic attempts. Anesth Analg, 2004; 99: 607-613.

- Ghamande SA, Arroliga AC, Ciceri DP. Let's make endotracheal intubation in the intensive care unit safe: difficult or not, the MACOCHA score is a good start. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2013; 187: 789-790.

- Jabbour-Khoury SI, Dabbous AS, Rizk LB, Jalad NM, Bartelmaos TE, El-Khatib MF, Baraka As. A combination of alfentanil-lidocaine-propofol provides better intubation conditions than fentanyl-lidocaine-propofol in the absence of muscle relaxants. CAN J ANESTH, 2003; 50: 116-120.