Primary Rectal Lymphoma: A Rare Neoplasm of the Rectum

Farhad F*, Zabihullah S and Mohammad TA

Department of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, Kabul University of Medical Sciences, Kabul, Afghanistan

Received Date: 15/09/2020; Published Date: 28/09/2020

*Corresponding author: Farhad Farzam, Department of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, Kabul University of Medical Sciences, Kabul, Afghanistan. Tel: 93792812125 ; E-mail: fa.farhad.fa@gmail.com

Abstract

The primary rectal lymphoma is a very rare disease. It constitutes about 0.05% of all primary rectal malignancy. Colorectal lymphoma predominantly affects males in their 40s to 60s. Men are affected twice as often as women. As most patients with rectal lymphoma complain from non‑specific symptoms, therefore, it results in late diagnosis and an advanced stage at presentation. Abdominal CT scan, endoscopy, and histopathology are the most commonly performed and useful diagnostic tests. We present a case of a 40-year-old man with history of rectal bleeding, alternative diarrhea, constipation, abdominal cramps, and discomfort. The CT features suggested the diagnosis of primary rectal lymphoma which was confirmed by histopathologic.

Keywords: Rectal lymphoma; Computed Tomography; Histopathology; Endoscopy

Background

Lymphomas are hematologic malignancies (malignant lymphocytes), classified as Hodgkin’s and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma [1]. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma is divided into nodal and extra nodal (40%) subtypes. The most common site of extra nodal involvement is gastrointestinal tract [1,2]. Lymphoma of the gastrointestinal tract happens primary or as part of a generalized process [3]. The most frequent colonic location is the cecum (70%), followed by the rectum and ascending colon [4]

The primary rectal lymphoma is a very rare entity [2, 5, 7, 8]. It constitutes about 0.05% of all primary rectal malignancy [5].

The guidelines include absence of palpable peripheral lymphadenopathy, absence of mediastinal adenopathy, normal peripheral blood smear; regional lymph nodes (excluding retro-peritoneal lymph nodes), absence of hepatic and splenic involvement [1,4].

The prevalence of primary malignancies has increased in the recent years, however, due to improvements in cancer diagnosis and treatment the survival of the cancer patients has increased noticeably [6]. Patients often present late with nonspecific symptoms, in result have advanced disease at the time of diagnosis [7].

Case Presentation

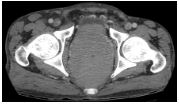

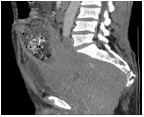

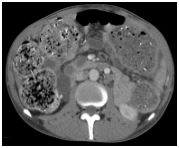

A 40-year-old man with history of rectal bleeding, alternative diarrhea and constipation, abdominal cramps and discomfort continued for 3 months referred for abdominal CT scan. The CT scan was performed which shows; significant concentric mural thickening in the rectum and recto-sigmoid junction resulting in partial obliteration of the rectal lumen. The maximum thickness of the involved segment was measured 28mm. The length of the involved segment was measured approximately 16cm. The meso-rectum was obliterated (Figures:1,2). The colons proximal to involved segment were dilated and fecal loaded (Figure: 3). The pelvic organs such as urinary bladder and prostate gland were not invaded by the lesion and the fat plane between the rectum and prostate was respected. Multiple enlarged lymph nodes were also seen along the bilateral internal iliac lymphatic chains (Figures: 4). The liver and spleen show normal size, outline with homogeneous contrast enhancement without any mass lesion (Figure: 5). Subsequently, the patient was referred for histopathologic work up and the diagnosis was non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.

Figure 1: Contrast enhanced axial CT demonstrates significant concentric mural thickening in the rectum and recto-sigmoid junction resulting in partial obliteration of the rectal lumen. The maximum thickness of the involved segment was measured 28mm.

Figure 2: Contrast enhanced sagittal CT demonstrates significant concentric mural thickening in the rectum and recto-sigmoid junction resulting in partial obliteration of the rectal lumen. The length of the involved segment was measured approximately 16cm.

Figure 3: Contrast enhanced axial CT from the mid-abdomen demonstrates significant dilated and fecal loaded colons.

Figure 4: Contrast enhanced axial CT demonstrates significant concentric mural thickening in the rectum and recto-sigmoid junction. Multiple nodal masses are present along the right and left internal iliac lymphatic chains.

Figure 5: Contrast enhanced axial CT from the upper-abdomen demonstrates no sign of liver and spleen involvement.

Discussion

The gastrointestinal tract is one of the most common extra nodal sites of lymphoma, however, primary rectal lymphoma remains the rarest disorder of all primary gastrointestinal lymphomas, accounting for 0.1‑0.6% of all colonic malignancies and 0.05% of all primary rectal malignancies [1-9]. Intestinal lymphomas are classified as B-cell lymphomas accounts for 85% and T cell lymphomas accounts for 15% [4,6]. Colorectal lymphoma predominantly affects males in their 40s to 60s. The mean age at diagnosis is 55 years. Men are affected twice as often as women [3,6]. Most of patients with rectal lymphoma present with non‑specific symptoms or negative rectal biopsy, which often leads to delay in diagnosis and an advanced stage at presentation [1]. The most common symptoms in majority of the patients are; abdominal pain, changes in bowel habit, weight loss, palpable abdominal mass or lower gastro-intestinal bleeding. Complete obstruction and perforation are relatively rare in patients with colorectal lymphoma [3,6]. Abdominal CT scan, endoscopy and histopathologic examinations are the most commonly performed and useful diagnostic tests [4]. The radiological features of colorectal lymphoma are variable and significantly intersects with other benign and malignant entities of the colorectal region [6]. Computed Tomography (CT) is most often used to evaluate and stage the colorectal lymphoma than other imaging modalities. CT scans can give extra-luminal information regarding tumor characteristics, depth of invasion, length of involvement and regional lymph node involvement as well as the status of the neighboring structures [2].

The variety of findings includes; circumferential involvement of the rectum, as polypoid mass, focal mucosal nodularity and diffuse ulcerative or nodular lesions. The rectal lymphoma has radiologic resemblances with rectal adenocarcinomas. Occasionally, it mimics radiologic features of inflammatory bowel disease. Tissue biopsy is used to confirm the diagnosis [2]. If there is an infiltrative process of the rectum associated with extensive pelvic lymphadenopathy, lymphoma should be the primary consideration in the differential diagnosis and must be excluded by endoscopic biopsy. However, if lymphadenopathy is not associated with a colorectal lymphoma, it might be difficult to distinguish it from rectal adenocarcinoma by radiological features [4].

Conclusion

Colorectal lymphoma is a rare disease, accounting for a small proportion of both colorectal malignancies and gastrointestinal lymphoma. It predominantly affects males between the 5th and 6th decade of life and most commonly occurs in the cecum. The patient presents with abdominal pain and loss of weight and due to the nonspecific nature of these symptoms, patients frequently present late with advanced loco‐regional disease, therefore, in an infiltrative process of the rectum associated with extensive pelvic lymphadenopathy, the primary hypothesis should be lymphoma [2,7].

References:

- Jiang C, Gu L, Luo M, Xu Q, Zhou H. Primary rectal lymphoma: A case report and literature review. Oncology letters. 2015;10:43-44.

- Quayle FJ, Lowney JK. Colorectal lymphoma. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery. 2006; 19: 049-053.

- Stanojevic GZ, Nestorovic MD, Brankovic BR, Stojanovic MP, Jovanovic MM, Radojkovic MD. Primary colorectal lymphoma: an overview. World journal of gastrointestinal oncology. 2011;3:14.

- Ardakani JV, Rashidian N, Adman AA, Keramati MR. Rectal lymphoma: report of a rare case and review of literature. Acta Medica Iranica. 2014;52:791-794.

- Shakya VC, Agrawal CS, Sah P, Pradhan A, Adhikary S. Rare location of primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma in the rectum. Journal of Nepal Medical Association. 2013;52.

- Ren Y, Chen Z, Su C, Tong H, Qian W. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in colon confounded by prior history of colorectal cancer: A case report and literature review. Oncology letters. 2016;11:1493-1495.

- Wong MTC, Eu KW. Primary colorectal lymphomas. Colorectal disease. 2006;8:586-591.

- Kang H, Connell JB, Leonardi MJ, Maggard MA, McGory ML. Ko CY. Rare tumors of the colon and rectum: a national review. International journal of colorectal disease. 2007;22:183-189.

- Castro-Poças F, Araújo T, Duarte A, Lopes C, Mascarenhas-Saraiva M. Rectal follicular lymphoma. International journal of colorectal disease. 2016;31:479-479.