A Rare Case Report of Multiple and Large Small Bowel Neuroendocrine Tumours in a 50 Year Old Lady

Harsh M*

Department of General Surgery, Government Medical College and Hospital, India

Received Date: 18/07/2020; Published Date: 13/08/2020

*Corresponding author: Harsh Rajeev Mehta, Department of General Surgery, Government Medical College and Hospital, Aurangabad, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: harshees81@gmail.com

Abstract

Small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors are the most common type of neuroendocrine tumors and small bowel neoplasms. The clinical presentation varies from asymptomatic incidentally detected localized lesions to lethal metastatic disease with carcinoid syndrome [2].

A 50 year old lady presented with chief complaints of lump in upper abdomen associated with dull aching pain since 3 months. Cect scan was suggestive of a probable gastrointestinal stromal tumour for which patient underwent elective laparotomy. Postoperatively on the basis of histopathology a diagnosis of neuroendocrine tumor was made and confirmed with immunohistochemistry. Approximately 90% of duodenal NET’s are not associated with clinical syndrome. It is a rare diagnosis with incidence of 0.5/100,000.

Patients with well differentiated tumours diagnosed in early stage have a good prognosis with an 85% overall 5year survival rate.

Keywords: Neuroendocrine; Gastrointestinal; Stromal; Duodenum

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumors are a heterogeneous group of neoplasms arising from various anatomical sites with the majority originating from small intestine and pancreas. They originate in the enterochromaffin cells of the aerodigestive tract. The underlying pathogenic mechanisms have been poorly characterised due to relative rarity.1

Small intestinal neuroendocrine tumors are the most common type of neuroendocrine tumors and small bowel neoplasms. The clinical presentation varies from asymptomatic incidentally detected localized lesions to lethal metastatic disease with carcinoid syndrome [2].

Functional neuroendocrine tumors are characterised by a clinical syndrome caused by excess hormonal secretion while non-functional neuroendocrine tumors are hormonally silent [3]. Intestinal neuroendocrine tumors have distinct features depending on their site of origin. Neuroendocrine tumors originating in the duodenum are not well characterized. Many are discovered incidentally during endoscopy [4]. Unlike other midgut neuroendocrine tumors, they are not commonly associated with the typical carcinoid syndrome. NET’s usually have an indolent clinical course, but tumor behavior varies widely depending on 2017 WHO (World Health Organization) grading, based on Ki-67 proliferation index and mitotic count [5].

Case Report

A 50 year old lady presented with chief complaints of lump in upper abdomen associated with dull aching pain since 3 months. There were no associated complaints of pain, fever, vomiting, constipation, diarrhoea, passage of blood in urine or stools, breathlessness, loss of weight or appetite and no complaint of other swellings in the body.

Patient was not a known case of diabetes mellitus, hypertension, heart disease, asthma or any other major illnesses. Patient is not a known alcoholic, smoker or drug addict. There is history of attaining menopause 5 years ago. Presently patient bears two children. On physical examination, patient was vitally stable. Per abdomen examination was soft to touch, non-tender with no guarding or rigidity felt. A lump of 15x8cm was felt in left hypochondriac and epigastric region, firm in consistency, immobile, non-tender with no local rise in temperature and with a smooth overlying surface. Per vaginal and per rectal examination had no abnormal findings. Routine lab investigations were within normal limits.

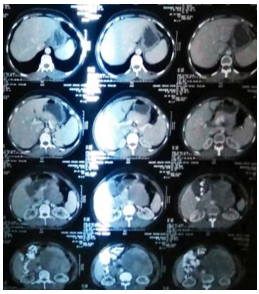

Patient was referred with a contrast enhanced computed tomography scan of abdomen and pelvis which was suggestive of:

1) A large well-defined solid heterogenously enhancing exophytic mass lesion of size 12x8cm containing non enhancing necrotic areas, arising from third part of duodenum.

2) Two well defined nodular enhancing lesions of approximate size 2x1 cm and 3x1cm from second part of duodenum.

Following above findings, CT was suggestive of a probable gastrointestinal stromal tumour with paraduodenal nodes.

Figure 1: Shows extent of mass on cect scan.

Figure 2: Showing extent and involvement of surrounding structures.

An upper gastrointestinal endoscopy was performed which was within normal limits. Usg guided biopsy or fnac was not done due to high vascularity of tumour.

Following investigations and anesthesia fitness, patient was posted for an elective exploratory laparotomy. Intraoperatively:

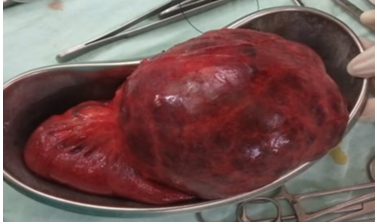

- There was evidence of a large 15x8x6cm exophytic growth from third and fourth part of duodenum, duodenojejunal flexure and proximal jejunal segment.

- Another 4x2cm and 3x2cm growths were seen arising from second part of duodenum.

Intraoperative decision was taken to perform whipple’s procedure. Resection of the large tumor with associated jejunal segment was done with primary closure of proximal and distal duodenum. Cholecystectomy was done with resection of pylorus, duodenum and part of pancreas followed by sequential pancreaticojejunostomy, choledochojejunostomy, gastrojejunostomy and feeding jejunostomy.

Figure 3: Shows growth arising from duodenum and jejunum.

Figure 4: Showing complete specimen after excision.

Postoperatively patient was managed aggressively and closely monitored. Multiple blood transfusions and parenteral nutrition were supplied consecutively. Feeding jejunostomy feeds were started on fifth day postoperatively. Abdominal drain in subhepatic space was removed on the sixth day while the pelvic drain was removed on the tenth day postoperatively.

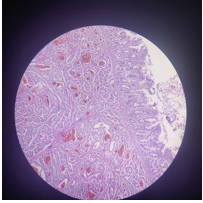

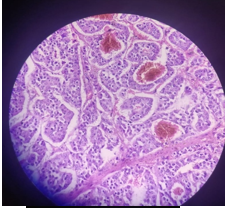

Histopathology report was as follows:

- Grade 1 neuroendocrine tumour of duodenum with low mitotic activity and lack of necrosis.

- Multiple neuroendocrine tumours of mesentery.

- Resected ends of duodenum and jejunum were free of tumour.

- Gall bladder, pancreas and pylorus were free of tumour

Further histopathology block were sent for Immunohistochemistry and KI 67 to enable exact grading that showed mitotic index less than 1, that was suggestive of a low grade, well differentiated tumour, following which patient was discharged on feeding jejunostomy and oral feeds and followed up after two and four weeks respectively.

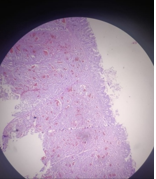

Figure 5: Showing histopathological findings.

Figure 6: Showing histopathological grading and findings.

Figure 7: Depicting hsitopathological findings of neuroendocrine tumor.

At follow up, ultrasonography of abdomen and pelvis was done which showed no evidence of any anastomotic leak. Feeding jejunostomy was removed and patient was continued on complete oral feeds.

Discussion

The annual incidence of small intestinal carcinoids is nearly 0.5/100,000, they account for a small proportion of intestinal neoplasms while colorectal adenocarcinomas are 60 times more frequent [6]. Duodenal NETs comprise 1%-3% of all primary duodenal tumors and 2.8% of all carcinoid tumors [6]. The age-adjusted annual incidence of NETs arising from jejunum and ileum is 0.67 per 100000. Being a rare malignancy, investigation regarding its pathophysiology and information on classification of these tumors has been limited till recent times. Duodenal NETs are usually diagnosed in the sixth decade with a male predominance [7,8].

There are five types of duodenal NET’s: Duodenal gastrinoma [the most common type] duodenal somatostatinoma, non-functioning duodenal NETs, duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine duodenal carcinomas.

Majority of duodenal NET’s are small, single lesions, usually limited to the mucosa and submucosa. Regional lymph node metastases may be found in up to 60% of cases, while liver metastasis usually occur in less than 10% [7]. Approximately 90% of duodenal NET’s are not associated with clinical syndrome, as majority of diagnosis are made accidentally during a routine workup or if the patient develops symptoms attributable to the mass itself [7]. Most frequently reported presenting symptoms include pain, jaundice (more frequent in peri-ampullary NET’s), nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, obstruction, active bleeding or anemia. In the minority of duodenal NET’s that cause a functional syndrome the two main presentations are Zollinger-Ellison syndrome and carcinoid syndrome.

NET’s of jejunum and ileum are usually diagnosed in the sixth or seventh decade but as opposed to duodenal NET’s, have no gender preference. Most of them are nonfunctioning tumors but about 20% of patients show liver metastases and may present with carcinoid syndrome. At diagnosis, lesions are commonly > 2 cm, with invasion of muscularis propria and metastasis to regional lymph nodes. Multiple lesions may be found in up to 40% of cases [9].

USG plays a limited role in the imaging of small bowel NETs. The most common imaging study obtained for the diagnosis of small bowel NETs is a multiphase CT scan. Gastrointestinal NET’s are graded according to the 2010 WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system based on the proliferative index, which is assessed by the percentage of cells that stain positively for Ki-67 and mitotic rate. The accepted surgical approach for resection of small bowel NET’s is an open abdominal operation, to achieve the goals of careful palpation of the entire small bowel and adequate resection of mesenteric lymph nodes while preserving vascular inflow and outflow to the remainder of the intestine. The need for resecting the primary tumour is to treat or avoid the situations that lead to symptoms, that is, bowel obstruction, bleeding, mesenteric fibrosis, peritoneal dissemination and reducing the risk of further metastasis.

In our case there was a vague clinical presentation of an abdominal lump with only dull aching pain for which a preoperative diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumour was made on cect scan. The tumour proved to be a neuroendocrine tumour on histopathology of the operative specimen which was a rare incidental finding.

Conclusion

Small intestinal NET’s are highly prone to metastasize, are fairly slow growing and associated with relatively favourable survival durations compared to other metastatic cancers. Regarding prognosis, patients with well-differentiated duodenal NET’s have an average global 5-year survival rate of nearly 85% [10]. It is 65% for patients with localized disease and only 36% for those with distant metastasis [11]. The stage of disease at diagnosis highly influence prognosis, with a 10-year survival of 95% for patients with local disease and 10% for those with distant metastases [11]. The prognosis of these NETs is generally unfavourable when compared with other location of tumours of comparable size since they have a higher tendency to grow and spread before the diagnosis is confirmed [12,13]. The diagnosed incidence of SINETs has tripled over the last three decades, likely from frequent use of abdominal radiologic imaging and endoscopic procedures [14,15].

References:

- Karpathakis A, Dibra H, Pipinikas C, Feber A, Morris T, Francis J, Oukrif D, Mandair D, Pericleous M, Mohmaduvesh M, Serra S. Prognostic impact of novel molecular subtypes of small intestinal neuroendocrine tumor. Clinical Cancer Research. 2016;22(1):250-8.

- Cho MY, Kim JM, Sohn JH, Kim MJ, Kim KM, Kim WH, Kim H, Kook MC, Park DY, Lee JH, Chang H. Current trends of the incidence and pathological diagnosis of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (GEP-NETs) in Korea 2000-2009: multicenter study. Cancer research and treatment: official journal of Korean Cancer Association. 2012;44(3):157.

- Strosberg J, Gardner N, Kvols L. Survival and prognostic factor analysis of 146 metastatic neuroendocrine tumors of the mid-gut. Neuroendocrinology. 2009;89(4):471-6.

- Chuah SK, Hu TH, Kuo CM, Chiu KW, Kuo CH, Wu KL, et al. Upper gastrointestinal carcinoid tumors incidentally found by endoscopic examinations. World J Gastroenterol Nov 28 2005;11(44):7028-32.

- Ohike, N, Adsay, N.V.; La Rosa, S. Mixed neuroendocrine-non-neuroendocrine neoplasms. In WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs, 4th ed.; Lloyd, R.V., Osamura, R.Y., Kloppel, G., Rosai, J., Eds.; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2017; p. 238.

- Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934-959.

- Hoffmann KM, Furukawa M, Jensen RT. Duodenal neuroendocrine tumors: Classification, functional syndromes, diagnosis and medical treatment. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:675-697.

- Kirshbom PM, Kherani AR, Onaitis MW, Hata A, Kehoe TE, Feldman C, Feldman JM, Tyler DS. Foregut carcinoids: a clinical and biochemical analysis. Surgery. 1999;126:1105-1110.

- Yao JC, Hassan M, Phan A, et al: One hundred years after “carcinoid”: Epidemiology of and prognostic factors for neuroendocrine tumors in 35,825 cases in the United States. J Clin Oncol 26:3063-3072, 2008.

- Soga J. Endocrinocarcinomas (carcinoids and their variants) of the duodenum. An evaluation of 927 cases. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2003;22:349-363.

- Eriksson B, Klöppel G, Krenning E, Ahlman H, Plöckinger U, Wiedenmann B, Arnold R, Auernhammer C, Körner M, Rindi G, et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of patients with digestive neuroendocrine tumors--well-differentiated jejunal-ileal tumor/carcinoma. Neuroendocrinology. 2008;87:8-19.

- Burke AP, Thomas RM, Elsayed AM, Sobin LH. Carcinoids of the jejunum and ileum: an immunohistochemical and clinicopathologic study of 167 cases. Cancer. 1997;79:1086-1093.

- Strodel WE, Talpos G, Eckhauser F, Thompson N. Surgical therapy for small-bowel carcinoid tumors. Arch Surg. 1983;118:391-397.