Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy (HCM) Mimicking Acute Coronary Syndrome

Ameur Ameur*, Rhemimet Chaimae and Abouchrif Yousra

Clinical cardiology service, Ibn Sina hospital, Rabat, Morocco

Received Date: 06/08/2023; Published Date: 21/12/2023

*Corresponding author: Dr. Ameur Asmaa, Clinical cardiology service, Ibn Sina hospital, Rabat, Morocco

Abstract

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy represents a very broad nosological framework, and can be responsible for different clinical presentations. Among these presentations, there is a painful form, with symptoms that can simulate acute coronary syndrome. We report the case of a patient who illustrates this differential diagnosis problem between the existence of an unrecognized HCM and an acute coronary syndrome.

Introduction

Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM) is the most common inherited cardiac disorder, affecting approximately 1 in 500 patients in the general population [1,2]. Its etiology lies mostly in mutations involving the sarcomeric proteins. HCM is typically inherited via the autosomal dominant pattern and characterized by variable degrees of ventricular hypertrophy and different clinical phenotypes. By definition, it is characterized by a marked increase in left ventricular wall thickness (15 mm, or>13 mm in family members of patients with HCM or in conjunction with a positive genetic test) of a non-dilated left ventricle, in the absence of abnormal loading conditions (such as aortic stenosis, systemic hypertension, etc.) [3,4]. We present a case who was initially thought to have an acute coronary syndrome but who was later diagnosed to have a hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Case Report

This is a 45-year-old patient, with chronic smoking as cardiovascular risk factors, with no particular medical history or sudden death in the family, who reported for 2 years class II angina according to Canadian Cardiovascular Society (CCS) associated with stage II dyspnea according to the classification of New York Heart Association (NYHA). The patient neglected this symptomatology, until the day of his admission when the patient presented with infarctoid chest pain.

Clinical examination at his admission found a patient conscious, still suffering, eupneic at rest, supporting supine position. Arterial Tension was 120/70mmHg, with a heart rate of 78bats/min with an ejection systolic murmur at the aortic focus without signs of right or left heart failure.

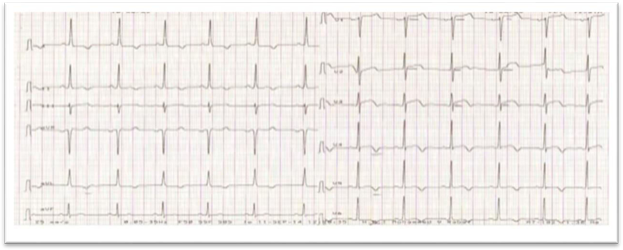

The initial ECG showed a atrial fibrillation with an average ventricular cadence at 78bp, concave ST segment elevation in apicolateral leads (V4, V5, V6, DI and AVL), negative T wave in inferior leads, as well as left ventricular hypertrophy (Figure 1).

Figure 1: ECG.

The initial diagnosis of STEMI was established. Coronary angiography performed however showed normal coronary arteries without significant stenosis.

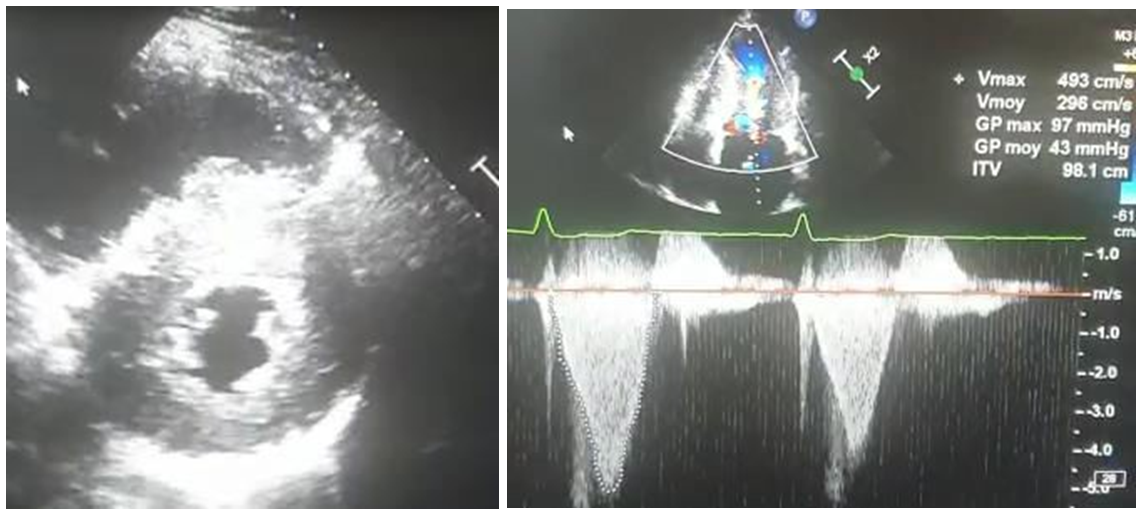

A posteriori echocardiography concluded to hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (SIV=25mm, PP= 21mm) with dynamic obstruction (maximal Gradient= 97mmhg), atrial dilatation and undilated left ventricle with good systolic function (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Echocardiography: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy with dynamic obstruction (maximal Gradient= 97mmhg).

Cardiac Magnetic Resonance showed an aspect of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in its medio-ventricular form realizing an hourglass appearance with atrial dilatation (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Cardiac Magnetic Resonance: hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in its medio-ventricular form.

Discussion

Patients with HCM may be completely asymptomatic, but will usually present with symptoms related to LVOT obstruction and diastolic dysfunction (dyspnea, exercise intolerance, dizziness, and near syncope or syncope), Chest pain is more common in younger patients and may signal cardiac ischemia.

Most patients with HCM will have an abnormal ECG. Characteristic findings of LVH are common and include high-voltage R waves in the anterolateral leads (V4, V5, V6, DI, and aVL), Prominent R waves may be present in leads V1 and V2 as well. The most frequent abnormalities found are large-amplitude QRS complexes consistent with LVH and associated ST-segment and T-wave changes. Deep, narrow Q waves are common in the inferior (II, III, aVF) and lateral (I, aVL, V5, and V6) leads in patients with septal hypertrophy and may mimic myocardial infarction. The morphology of the Q waves—deep and very narrow—is perhaps the most characteristic and specific finding of HCM. Although often these Q waves are mistaken for those of myocardial infarction [5].

Myocardial ischemia in the absence of epicardial coronary artery disease is common in HCM patients, it results from an imbalance between oxygen demand, increased by LVH, left ventricular outflow tract obstruction (LVOTO), diastolic dysfunction, and supply, decreased by small vessel disease, abnormal vascular response, increased resistance, and myocardial bridging. Among these mechanisms, the major cause of myocardial ischemia in HCM is microvascular dysfunction, which is multifactorial, resulting from vascular remodeling with arteriolar medial hypertrophy and intimal hyperplasia, fibrosis, myocyte disarray [6].

The cascade of events, beginning with morphologic and functional alterations in coronary microvasculature leading to ischemia, followed by myocyte necrosis, replacement fibrosis and LV remodeling with systolic dysfunction, ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death is conceptually attractive, explaining the natural history of some HCM patients [6].

Conclusion

In conclusion, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy is another non infarctional cause of ST segment elevation that emergency physicians should be aware of when assessing in patient with ST segment elevation on ECG.

References

- MacIntyre C, Lakdawala Management of atrialfibrillation in hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.Circulation, 2016; 133(19): 1901e1905.

- Maron BJ, Gardin JM, Flack JM, Gidding SS, Kurosaki TT, Bild DE. Prevalence of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in a general population of young Echocardiographic analysis of 4111 subjects in the CARDIA Study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in (Young) Adults.Circulation, 1995; 92(4): 785e789.

- Olivotto I, d'Amati G, Basso C, et Defining phenotypes and disease progression in sarcomeric cardiomyopathies: contemporary role of clinical investigations.Cardiovasc Res, 2015; 105(4): 409e423.

- Elliott PM, Anastasakis A, Borger Michael A, et al, Authors/Task Force ESC Guidelines on diagnosis and management of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: the Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Eur Heart J, 2014; 35(39): 2733e2779.

- Kelly BS, et Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: electrocardiographic manifestations and other important considerations for the emergency physician. American Journal of Emergency Medicine, 2007; 25: 72–79.

- Alexandra Uncovering hypertrophic cardiomyopathy pathophysiology --- the unsolved role of microvascular dysfunction.Revista Portuguesa de Cardiologia, 2022; 41: 569-571.